.gif)

Daisy Bates (Australia)

Encyclopedia

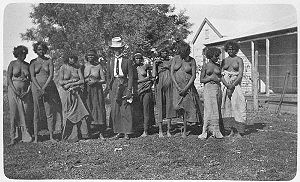

Daisy May Bates, CBE (16 October 1859 – 18 April 1951) was an Irish Australian

journalist, welfare worker and lifelong student of Australian Aboriginal culture and society. She was known among the native people as 'Kabbarli' (grandmother).

, Ireland

in 1859. Her mother, Bridget (née Hunt), died of tuberculosis

on 20 December 1862. Her father married Mary Dillon on 21 September 1864 and died in route to the United States

, so Bates was raised, by relatives, in Roscrea

and educated at the National School in the town.

on the R.M.S. Almora, by which time she had changed her name to Daisy May O'Dwyer. Some accounts (based on Bates's own claims) say that she left Ireland for 'health reasons', but Bates's biographer Julia Blackburn

discovered that, after getting her first job as a governess

in Dublin at age 18, there was a scandal, presumably sexual in nature, which resulted in the young man of the house taking his own life. Bates was forced to leave Ireland and, keen to cover up her sordid past, she re-invented her history, setting a pattern for the rest of her life. It was not until long after her death that the true facts of her early life emerged.

Bates settled first at Townsville

, Queensland

allegedly staying first at the home of the Bishop

of North Queensland and later with family friends who had migrated earlier. Bates had travelled with Ernest C. Baglehole and James C. Hann, amongst others, on the later stage of her journey. Both Baglehole and Hann had boarded at Batavia for the journey to Australia. Hann's family, through William Hann's donation of £1000, had been very generous to the construction of St James Church of England some few years before Bishop Stanton had arrived at Townsville. Bates found temporary accommodation with the Bishop. She subsequently found employment as a governess on Fanning Downs Station

.

Records show that she married poet and horseman Breaker Morant

(Harry Morant aka Edwin Murrant) on 13 March 1884; the union lasted only a short time and Bates reputedly threw Morant out because he failed to pay for the wedding and stole some livestock. Significantly, they were never divorced. Morant's biographer Nick Bleszynski suggests that Bates played a more important role in Morant's life than has been previously thought, and that it was she who convinced him to change his name from Edwin Murrant to Harry Harbord Morant.

Soon after her failed marriage to Morant, Bates moved to New South Wales

. She said that she became engaged to Philip Gipps but he died before they could marry. This is probably fantasy. She then met John (Jack) Bates and they married on 17 February 1885; like Morant, he was a breaker of wild horses, bushman and drover

. The bigamous nature of their marriage was kept secret during Bates's lifetime. She also found time to marry Ernest C. Baglehole on 10 June 1885 at St Stephen's near Sydney. Although he is shown as being a seaman he was the son of a wealthy London family and had become a ship's officer after completing an apprenticeship and this might have been an attraction for Daisy. She first met Baglehole when he was one of 6 passengers who came aboard "The Almora" at Batavia and presumably he had left his ship there and was on his way to join another in Australia.

Their only child, Arnold Hamilton Bates, was born in Bathurst

, New South Wales

on 26 August 1886. The marriage was not a happy one, probably because Jack, being a drover and bushman, was away for long periods. In February 1894, Bates returned to England

, telling Jack that she would only return when he had a home established for her. She arrived in England penniless but eventually found a job as a journalist

. It was not until 1899 that she heard from her husband again, who wrote saying that he was looking for a property in Western Australia

.

about the cruelty of West Australian settlers to Aborigines

. As Bates was preparing to return to Australia, she wrote to The Times offering to make full investigations and report the results to them. Her offer was accepted and she sailed back to Australia in August 1899. In all, Bates devoted more than 35 years of her life to studying Aboriginal life, history, culture, rites, beliefs and customs. Living in a tent in small settlements from Western Australia to the edges of the Nullarbor Plain

, notably at Ooldea

in South Australia, she researched and wrote millions of words on the subject. She was also famed for her strict lifelong adherence to Edwardian fashion

, including boots, gloves and a veil.

She also worked tirelessly for Aboriginal welfare, setting up camps to feed, clothe and nurse the transient population, drawing on her own income to meet the needs of the aged. She fought against the policy of having native people assimilated into white Australian society and resisted the sexual exploitation of Aboriginal women by white men. She was said to have worn pistols even in her old age and to have been quite prepared to use them to threaten police when she caught them mistreating 'her' Aborigines.

In spite of her fascination with their way of life, Bates was convinced that the Australian Aborigines were a dying race and that her mission was to record as much as she could about them before they disappeared. She dismissed people of part Aboriginal descent as worthless and wrote in the Perth Sunday Times on 12 June 1921, 'As to the half-castes, however early they may be taken and trained, with very few exceptions, the only good half-caste is a dead one.'

, invested some of her money in property as a security for her old age, bought note books and supplies and left for the state's remote north-west to gather information on Aborigines and the effects of white settlement.

She wrote articles about conditions around Port Hedland

and other areas for geographical society journals, local newspapers and The Times. This experience kindled her life-long interest in the lives and welfare of Aboriginal people in Western and South Australia

.

Based at the Beagle Bay Mission near Broome

, Bates, now thirty-six, began her life's work. Her accounts, among the first attempts at a serious study of Aboriginal culture, were published in the Journal of Agriculture and later by anthropological

and geographical

societies in Australia and overseas.

While at the mission she also compiled a local dictionary of several dialects, comprising some two thousand words and sentences, as well as notes on legends and myths. In April 1902 Bates, accompanied by her son and her husband, set out on a droving trip from Broome to Perth. It provided good material for her articles but after spending six months in the saddle and travelling four thousand kilometres, Bates knew that her marriage was over.

Following her final separation from Bates in 1902, she spent most of the rest of her life in outback Western and South Australia, studying and working for the remote Aboriginal tribes, who were being decimated by the incursions of European settlement and the introduction of modern technology, western culture and exotic diseases.

In 1904, the Registrar General's Department of Western Australia appointed her to research Aboriginal customs, languages and dialects, a task which took nearly six years to compile and arrange the data. Many of her papers were read at Geographical and Royal Society

meetings.

In 1910-11 she accompanied anthropologist A. R. Brown (later Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown

In 1910-11 she accompanied anthropologist A. R. Brown (later Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown

) and writer and biologist E. L. Grant Watson

on a Cambridge

ethnological expedition to inquire into Western Australian marriage customs. She was appointed a 'Travelling Protector

' with a special commission to conduct inquiries into all native conditions and problems, such as employment on stations, guardianship and the morality of native and half-caste women in towns and mining camps.

Bates later came into conflict with Radcliffe-Brown because she sent him her manuscript report of the expedition. Much to Bates's chagrin, it was not returned for many years and when it came back it was heavily annotated with Radcliffe-Brown's critical remarks. The conflict culminated in a famous incident at a symposium, where Bates accused Radcliffe-Brown of plagiarism—Bates was scheduled to speak after Radcliffe-Brown had presented his paper, but when she rose it was only to compliment him sarcastically on his presentation of her work, after which she resumed her seat.

, Bates continued her work on her own, financing it by selling her cattle station.

The same year she became the first woman ever to be appointed Honorary Protector of Aborigines at Eucla

. During the sixteen months she spent there, Bates changed from a semi-professional scientist and ethnologist to a staunch friend and protector of the Aborigines, deciding to live among them and look after them, and to observe and record their lives and lifestyle.

Bates stayed at Eucla until 1914, when she travelled to Adelaide

, Melbourne

and Sydney

to attend the Science Congress of the Association for the Advancement of Science. Before returning to the desert, she gave lectures in Adelaide which aroused the interests of several women's organisations.

During her years at Ooldea she financed the supplies she bought for the Aborigines from the sale of her property. To maintain her income she wrote numerous articles and papers for newspapers, magazines and learned societies. Through journalist and author Ernestine Hill

, Bates's work was introduced to the general public, although much of the publicity tended to focus on her sensational stories of cannibalism.

In August 1933 the Commonwealth Government invited Bates to Canberra

to advise on Aboriginal affairs. The next year she was created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by King George V

. More important to Bates was the opportunity to put her work in print.

where, with the help of Ernestine Hill

, she produced a series of articles for leading Australian newspapers, titled My Natives and I.

Aged seventy-one, she still walked every day to her office at The Advertiser

building. Later the Commonwealth Government paid her a stipend of $4 a week to assist her in putting all her papers and notes in order and prepare her manuscript. But with no other income it was impossible for her to remain in Adelaide so she moved to the village settlement of Pyap on the Murray River

where she pitched her tent and set up her typewriter.

In 1938, she published The Passing of the Aborigines which caused controversy due to its claims of cannibalism

In 1918 she tried, through the Australian Army, to contact her son Arnold, who by then was serving in France. Later, in 1949, she contacted the Army again, through the RSL

, in an effort to communicate with him. Arnold was living in New Zealand but refused to have anything to do with his mother.

Daisy Bates died on 18 April 1951, aged 91. She is buried at Adelaide's North Road Cemetery. An episode in her life was the basis for Margaret Sutherland

's chamber opera

The Young Kabbarli

(1964) and her involvement with the aboriginal people is the basis for the 1983 lithograph The Ghost of Kabbarli by Susan Dorothea White

.

Irish Australian

Irish Australians have played a long and enduring part in Australia's history. Many came to Australia in the eighteenth century as settlers or as convicts, and contributed to Australia's development in many different areas....

journalist, welfare worker and lifelong student of Australian Aboriginal culture and society. She was known among the native people as 'Kabbarli' (grandmother).

Early life

Bates was born as Margaret Dwyer in County TipperaryCounty Tipperary

County Tipperary is a county of Ireland. It is located in the province of Munster and is named after the town of Tipperary. The area of the county does not have a single local authority; local government is split between two authorities. In North Tipperary, part of the Mid-West Region, local...

, Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

in 1859. Her mother, Bridget (née Hunt), died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

on 20 December 1862. Her father married Mary Dillon on 21 September 1864 and died in route to the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, so Bates was raised, by relatives, in Roscrea

Roscrea

Roscrea is a small heritage town in North Tipperary, Ireland. The town has a population of 4,910. Its main industries include meat processing and pharmaceuticals. It is a civil parish in the historical barony of Ikerrin...

and educated at the National School in the town.

Australia

On 22 November 1882, aged 23, she emigrated to AustraliaAustralia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

on the R.M.S. Almora, by which time she had changed her name to Daisy May O'Dwyer. Some accounts (based on Bates's own claims) say that she left Ireland for 'health reasons', but Bates's biographer Julia Blackburn

Julia Blackburn

Julia Blackburn is a British author of both fiction and non-fiction. She is the daughter of poet Thomas Blackburn and artist Rosalie de Meric...

discovered that, after getting her first job as a governess

Governess

A governess is a girl or woman employed to teach and train children in a private household. In contrast to a nanny or a babysitter, she concentrates on teaching children, not on meeting their physical needs...

in Dublin at age 18, there was a scandal, presumably sexual in nature, which resulted in the young man of the house taking his own life. Bates was forced to leave Ireland and, keen to cover up her sordid past, she re-invented her history, setting a pattern for the rest of her life. It was not until long after her death that the true facts of her early life emerged.

Bates settled first at Townsville

Townsville, Queensland

Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Australia, in the state of Queensland. Adjacent to the central section of the Great Barrier Reef, it is in the dry tropics region of Queensland. Townsville is Australia's largest urban centre north of the Sunshine Coast, with a 2006 census...

, Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

allegedly staying first at the home of the Bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

of North Queensland and later with family friends who had migrated earlier. Bates had travelled with Ernest C. Baglehole and James C. Hann, amongst others, on the later stage of her journey. Both Baglehole and Hann had boarded at Batavia for the journey to Australia. Hann's family, through William Hann's donation of £1000, had been very generous to the construction of St James Church of England some few years before Bishop Stanton had arrived at Townsville. Bates found temporary accommodation with the Bishop. She subsequently found employment as a governess on Fanning Downs Station

Station (Australian agriculture)

Station is the term for a large Australian landholding used for livestock production. It corresponds to the North American term ranch or South American estancia...

.

Records show that she married poet and horseman Breaker Morant

Breaker Morant

Harry 'Breaker' Harbord Morant was an Anglo-Australian drover, horseman, poet, soldier and convicted war criminal whose skill with horses earned him the nickname "The Breaker"...

(Harry Morant aka Edwin Murrant) on 13 March 1884; the union lasted only a short time and Bates reputedly threw Morant out because he failed to pay for the wedding and stole some livestock. Significantly, they were never divorced. Morant's biographer Nick Bleszynski suggests that Bates played a more important role in Morant's life than has been previously thought, and that it was she who convinced him to change his name from Edwin Murrant to Harry Harbord Morant.

Soon after her failed marriage to Morant, Bates moved to New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

. She said that she became engaged to Philip Gipps but he died before they could marry. This is probably fantasy. She then met John (Jack) Bates and they married on 17 February 1885; like Morant, he was a breaker of wild horses, bushman and drover

Drover (Australian)

A drover in Australia is a person, typically an experienced stockman, who moves livestock, usually sheep or cattle, "on the hoof" over long distances. Reasons for droving may include: delivering animals to a new owner's property, taking animals to market, or moving animals during a drought in...

. The bigamous nature of their marriage was kept secret during Bates's lifetime. She also found time to marry Ernest C. Baglehole on 10 June 1885 at St Stephen's near Sydney. Although he is shown as being a seaman he was the son of a wealthy London family and had become a ship's officer after completing an apprenticeship and this might have been an attraction for Daisy. She first met Baglehole when he was one of 6 passengers who came aboard "The Almora" at Batavia and presumably he had left his ship there and was on his way to join another in Australia.

Their only child, Arnold Hamilton Bates, was born in Bathurst

Bathurst, New South Wales

-CBD and suburbs:Bathurst's CBD is located on William, George, Howick, Russell, and Durham Streets. The CBD is approximately 25 hectares and surrounds two city blocks. Within this block layout is banking, government services, shopping centres, retail shops, a park* and monuments...

, New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

on 26 August 1886. The marriage was not a happy one, probably because Jack, being a drover and bushman, was away for long periods. In February 1894, Bates returned to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, telling Jack that she would only return when he had a home established for her. She arrived in England penniless but eventually found a job as a journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

. It was not until 1899 that she heard from her husband again, who wrote saying that he was looking for a property in Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

.

Involvement with Australian Aboriginal people

At about this time a letter was published in The TimesThe Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

about the cruelty of West Australian settlers to Aborigines

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

. As Bates was preparing to return to Australia, she wrote to The Times offering to make full investigations and report the results to them. Her offer was accepted and she sailed back to Australia in August 1899. In all, Bates devoted more than 35 years of her life to studying Aboriginal life, history, culture, rites, beliefs and customs. Living in a tent in small settlements from Western Australia to the edges of the Nullarbor Plain

Nullarbor Plain

The Nullarbor Plain is part of the area of flat, almost treeless, arid or semi-arid country of southern Australia, located on the Great Australian Bight coast with the Great Victoria Desert to its north. It is the world's largest single piece of limestone, and occupies an area of about...

, notably at Ooldea

Ooldea, South Australia

Ooldea is a tiny settlement in South Australia. It is on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain, 863 km west of Port Augusta on the Trans-Australian Railway...

in South Australia, she researched and wrote millions of words on the subject. She was also famed for her strict lifelong adherence to Edwardian fashion

Fashion

Fashion, a general term for a currently popular style or practice, especially in clothing, foot wear, or accessories. Fashion references to anything that is the current trend in look and dress up of a person...

, including boots, gloves and a veil.

She also worked tirelessly for Aboriginal welfare, setting up camps to feed, clothe and nurse the transient population, drawing on her own income to meet the needs of the aged. She fought against the policy of having native people assimilated into white Australian society and resisted the sexual exploitation of Aboriginal women by white men. She was said to have worn pistols even in her old age and to have been quite prepared to use them to threaten police when she caught them mistreating 'her' Aborigines.

In spite of her fascination with their way of life, Bates was convinced that the Australian Aborigines were a dying race and that her mission was to record as much as she could about them before they disappeared. She dismissed people of part Aboriginal descent as worthless and wrote in the Perth Sunday Times on 12 June 1921, 'As to the half-castes, however early they may be taken and trained, with very few exceptions, the only good half-caste is a dead one.'

Western Australia

On her return voyage she met Father Dean Martelli, a Roman Catholic priest who had worked with Aborigines and who gave her an insight into the conditions they faced. She found a school and home for her son in PerthPerth, Western Australia

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia and the fourth most populous city in Australia. The Perth metropolitan area has an estimated population of almost 1,700,000....

, invested some of her money in property as a security for her old age, bought note books and supplies and left for the state's remote north-west to gather information on Aborigines and the effects of white settlement.

She wrote articles about conditions around Port Hedland

Port Hedland, Western Australia

Port Hedland is the highest tonnage port in Australia and largest town in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, with a population of approximately 14,000 ....

and other areas for geographical society journals, local newspapers and The Times. This experience kindled her life-long interest in the lives and welfare of Aboriginal people in Western and South Australia

South Australia

South Australia is a state of Australia in the southern central part of the country. It covers some of the most arid parts of the continent; with a total land area of , it is the fourth largest of Australia's six states and two territories.South Australia shares borders with all of the mainland...

.

Based at the Beagle Bay Mission near Broome

Broome, Western Australia

Broome is a pearling and tourist town in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, north of Perth. The year round population is approximately 14,436, growing to more than 45,000 per month during the tourist season...

, Bates, now thirty-six, began her life's work. Her accounts, among the first attempts at a serious study of Aboriginal culture, were published in the Journal of Agriculture and later by anthropological

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

and geographical

Geography

Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes...

societies in Australia and overseas.

While at the mission she also compiled a local dictionary of several dialects, comprising some two thousand words and sentences, as well as notes on legends and myths. In April 1902 Bates, accompanied by her son and her husband, set out on a droving trip from Broome to Perth. It provided good material for her articles but after spending six months in the saddle and travelling four thousand kilometres, Bates knew that her marriage was over.

Following her final separation from Bates in 1902, she spent most of the rest of her life in outback Western and South Australia, studying and working for the remote Aboriginal tribes, who were being decimated by the incursions of European settlement and the introduction of modern technology, western culture and exotic diseases.

In 1904, the Registrar General's Department of Western Australia appointed her to research Aboriginal customs, languages and dialects, a task which took nearly six years to compile and arrange the data. Many of her papers were read at Geographical and Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

meetings.

Alfred Radcliffe-Brown

Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was an English social anthropologist who developed the theory of Structural Functionalism.- Biography :...

) and writer and biologist E. L. Grant Watson

E. L. Grant Watson

Elliot Lovegood Grant Watson was a writer and biologist whose works combine the scrutiny of a scientist with the insight of the poet...

on a Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

ethnological expedition to inquire into Western Australian marriage customs. She was appointed a 'Travelling Protector

Protector of Aborigines

The role of Protectors of Aborigines resulted from a recommendation of the report of the Select Committee of the House of Commons on Aborigines . On 31 January 1838, Lord Glenelg, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies sent Governor Gipps the report.The report recommended that Protectors of...

' with a special commission to conduct inquiries into all native conditions and problems, such as employment on stations, guardianship and the morality of native and half-caste women in towns and mining camps.

Bates later came into conflict with Radcliffe-Brown because she sent him her manuscript report of the expedition. Much to Bates's chagrin, it was not returned for many years and when it came back it was heavily annotated with Radcliffe-Brown's critical remarks. The conflict culminated in a famous incident at a symposium, where Bates accused Radcliffe-Brown of plagiarism—Bates was scheduled to speak after Radcliffe-Brown had presented his paper, but when she rose it was only to compliment him sarcastically on his presentation of her work, after which she resumed her seat.

A "Protector of Aborigines"

After 1912, despite having earlier been appointed as Travelling Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia, her application to become the Northern Territory's Protector of Aborigines was rejected on basis of her genderGender

Gender is a range of characteristics used to distinguish between males and females, particularly in the cases of men and women and the masculine and feminine attributes assigned to them. Depending on the context, the discriminating characteristics vary from sex to social role to gender identity...

, Bates continued her work on her own, financing it by selling her cattle station.

The same year she became the first woman ever to be appointed Honorary Protector of Aborigines at Eucla

Eucla, Western Australia

Eucla is the easternmost locality in Western Australia, located in the Goldfields-Esperance region of Western Australia along the Eyre Highway, approximately west of the South Australian border...

. During the sixteen months she spent there, Bates changed from a semi-professional scientist and ethnologist to a staunch friend and protector of the Aborigines, deciding to live among them and look after them, and to observe and record their lives and lifestyle.

Bates stayed at Eucla until 1914, when she travelled to Adelaide

Adelaide

Adelaide is the capital city of South Australia and the fifth-largest city in Australia. Adelaide has an estimated population of more than 1.2 million...

, Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

and Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

to attend the Science Congress of the Association for the Advancement of Science. Before returning to the desert, she gave lectures in Adelaide which aroused the interests of several women's organisations.

During her years at Ooldea she financed the supplies she bought for the Aborigines from the sale of her property. To maintain her income she wrote numerous articles and papers for newspapers, magazines and learned societies. Through journalist and author Ernestine Hill

Ernestine Hill

Ernestine Hill was an Australian journalist, travel writer and novelist.-Life:Born in Rockhampton, Queensland, Hill attended All Hallows' School in Brisbane, and then Stott & Hoare's Business College, Brisbane...

, Bates's work was introduced to the general public, although much of the publicity tended to focus on her sensational stories of cannibalism.

In August 1933 the Commonwealth Government invited Bates to Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

to advise on Aboriginal affairs. The next year she was created a Commander of the Order of the British Empire by King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

. More important to Bates was the opportunity to put her work in print.

South Australia

She left Ooldea and went to AdelaideAdelaide

Adelaide is the capital city of South Australia and the fifth-largest city in Australia. Adelaide has an estimated population of more than 1.2 million...

where, with the help of Ernestine Hill

Ernestine Hill

Ernestine Hill was an Australian journalist, travel writer and novelist.-Life:Born in Rockhampton, Queensland, Hill attended All Hallows' School in Brisbane, and then Stott & Hoare's Business College, Brisbane...

, she produced a series of articles for leading Australian newspapers, titled My Natives and I.

Aged seventy-one, she still walked every day to her office at The Advertiser

The Advertiser (Australia)

The Advertiser is a daily tabloid-format newspaper published in the city of Adelaide, South Australia. First published as a broadsheet named "The South Australian Advertiser" on 12 July 1858, it is currently printed daily from Monday to Saturday. A Sunday edition exists under the name of the Sunday...

building. Later the Commonwealth Government paid her a stipend of $4 a week to assist her in putting all her papers and notes in order and prepare her manuscript. But with no other income it was impossible for her to remain in Adelaide so she moved to the village settlement of Pyap on the Murray River

Murray River

The Murray River is Australia's longest river. At in length, the Murray rises in the Australian Alps, draining the western side of Australia's highest mountains and, for most of its length, meanders across Australia's inland plains, forming the border between New South Wales and Victoria as it...

where she pitched her tent and set up her typewriter.

In 1938, she published The Passing of the Aborigines which caused controversy due to its claims of cannibalism

Cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh of other human beings. It is also called anthropophagy...

Final years

In 1941 she went back to her tent life at Wynbring Siding, east of Ooldea, and she remained there on and off until her health forced her back to Adelaide in 1945.In 1918 she tried, through the Australian Army, to contact her son Arnold, who by then was serving in France. Later, in 1949, she contacted the Army again, through the RSL

Returned and Services League of Australia

The Returned and Services League of Australia is a support organisation for men and women who have served or are serving in the Australian Defence Force ....

, in an effort to communicate with him. Arnold was living in New Zealand but refused to have anything to do with his mother.

Daisy Bates died on 18 April 1951, aged 91. She is buried at Adelaide's North Road Cemetery. An episode in her life was the basis for Margaret Sutherland

Margaret Sutherland

Margaret Sutherland was an Australian composer, probably the best-known female composer her country has produced....

's chamber opera

Chamber opera

Chamber opera is a designation for operas written to be performed with a chamber ensemble rather than a full orchestra.The term and form were invented by Benjamin Britten in the 1940s, when the English Opera Group needed works that could easily be taken on tour and performed in a variety of small...

The Young Kabbarli

The Young Kabbarli

The Young Kabbarli is a one-act chamber opera written in 1964 by the Australian composer Margaret Sutherland; it is her only work in the operatic genre. The libretto was by Maie Casey, based on poetry by Judith Wright and Shaw Neilson....

(1964) and her involvement with the aboriginal people is the basis for the 1983 lithograph The Ghost of Kabbarli by Susan Dorothea White

Susan Dorothea White

Susan Dorothea White , also called Sue White and Susan White, is an Australian painter, sculptor, and printmaker. She is a narrative artist and her work concerns the natural world and human situation, increasingly incorporating satire and irony to convey her concern for human rights and equality...

.

Further reading

- Blackburn, Julia. (1994) Daisy Bates in the Desert: A Woman's Life Among the Aborigines London, Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0436201119

- De Vries, Susanna. (2008) Desert Queen: The many lives and loves of Daisy Bates Pymble, N.S.W. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780732282431

- Reece, Bob. (2007) Daisy Bates: grand dame of the desert Canberra, A.C.T. National Library of Australia. ISBN 9780642276544

External links

- "Seven Sisters" - includes a collection of quotes by and about Daisy Bates

- Daisy Bates - A list of her papers held by University of Adelaide Library

- Daisy Bates - Guide to the papers at the National Library of Australia (including the rare maps)

- Daisy May Bates - Guide to records at the South Australian Museum Archives

- Works by Daisy Bates at Project Gutenberg Australia

- The Ghost of Kabbarli (Daisy Bates), lithograph (1983) by Susan Dorothea White