Constitution of the Roman Republic

Encyclopedia

The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten, uncodified, and constantly evolving. Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy

(as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy

(as was ancient Sparta

), or a monarchy

(as was Rome before

and, in many respects, after

the Republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements, thus creating three separate branches of government. The democratic element took the form of the legislative assemblies, the aristocratic element took the form of the Senate

, and the monarchical element took the form of the many term-limited executive magistrates

.

The ultimate source of sovereignty in this ancient republic, as in modern republics, was the demos (people). The People of Rome

gathered into legislative assemblies to pass laws and to elect executive magistrates. Election to a magisterial office resulted in automatic membership in the Senate (for life, unless impeached

). The Senate managed the day-to-day affairs in Rome, while senators presided over the courts. Executive magistrates enforced the law, and presided over the Senate and the legislative assemblies. A complex set of checks and balances developed between these three branches, so as to minimize the risk of tyranny and corruption, and to maximize the likelihood of good government. However, the separation of powers between these three branches of government was not absolute. Also, there was the frequent usage of several constitutional devices that were out of harmony with the genius of the Roman constitution. A constitutional crisis began in 133 BC, as a result of the struggles between the aristocracy and the common people. This crisis ultimately led to the collapse of the Roman Republic

and its eventual subversion

into a much more autocratic

form of government, the Roman Empire

.

, began in 753 BC, and ended in 510 BC. After the monarchy had been overthrown, and the Roman Republic

had been founded, the people of Rome began electing two Roman Consul

s each year. In 501 BC, the office of "Roman Dictator

" was created. In the year 494 BC, the Plebeians (commoners) seceded to the Mons Sacer

, and demanded of the Patricians (the aristocrats) the right to elect their own officials. The Patricians duly capitulated, and the Plebeians ended their secession. The Plebeians called these new officials "Plebeian Tribunes

", and gave these Tribunes two assistants, called "Plebeian Aediles

".

In 449 BC, the Senate promulgated the Twelve Tables

as the centerpiece of the Roman Constitution. In 443 BC, the office of "Roman Censor" was created, and in 367 BC, Plebeians were allowed to stand for the Consulship. The opening of the Consulship to the Plebeian class implicitly opened both the Censorship as well as the Dictatorship to Plebeians. In 366 BC, in an effort by the Patricians to reassert their influence over the magisterial offices, two new offices were created. While these two offices, the Praetor

ship and the Curule Aedileship

, were at first open only to Patricians, within a generation, they were open to Plebeians as well.

Beginning around the year 350 BC, the senators and the Plebeian Tribunes began to grow closer. The senate began giving Tribunes more power, and, unsurprisingly, the Tribunes began to feel indebted to the senate. As the Tribunes and the senators grew closer, Plebeian senators began to routinely secure the office of Tribune for members of their own families. Also around the year 350 BC, the Plebeian Council

(popular assembly) enacted a significant law (the "Ovinian Law") which transferred, from the Consuls to the Censors, the power to appoint new senators. This law also required the Censors to appoint any newly elected magistrate to the senate, which probably resulted in a significant increase in the number of Plebeian senators. This, along with the closeness between the Plebeian Tribunes and the senate, helped to facilitate the creation of a new Plebeian aristocracy. This new Plebeian aristocracy soon merged with the old Patrician aristocracy, creating a combined "Patricio-Plebeian" aristocracy. The old aristocracy existed through the force of law, because only Patricians had been allowed to stand for high office. Now, however, the new aristocracy existed due to the organization of society, and as such, this order could only be overthrown through a revolution.

In 287 BC, the Plebeians seceded to the Janiculum hill

. To end the secession, a law (the "Hortensian Law") was passed, which ended the requirement that the Patrician senators consent before a bill could be brought before the Plebeian Council for a vote. This was not the first law to require that an act of the Plebeian Council have the full force of law (over both Plebeians and Patricians), since the Plebeian Council had acquired this power in 449 BC. The ultimate significance of this law was in the fact that it robbed the Patricians of their final weapon over the Plebeians. The result was that the ultimate control over the state fell, not onto the shoulders of democracy, but onto the shoulders of the new Patricio-Plebeian aristocracy. The Hortensian Law resolved the last great political question of the earlier era, and as such, no important political changes occurred over the next 150 years (between 287 BC and 133 BC). The critical laws of this era were still enacted by the senate. In effect, the democracy was satisfied with the possession of power, but did not care to actually use it.

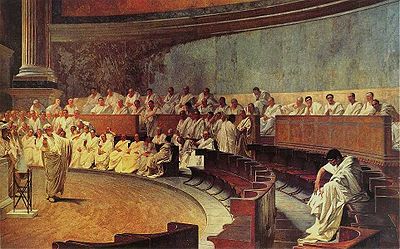

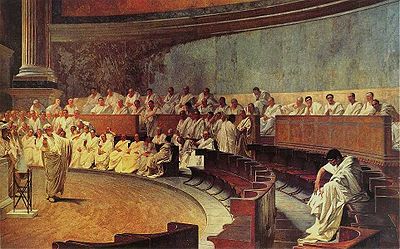

The Roman Senate was a political institution in the Roman Republic

The Roman Senate was a political institution in the Roman Republic

. The Roman senate's authority derived from Roman precedent, custom, and the high caliber of the senators. The senate's principal role was as an advisory council to the two Roman Consul

s on matters of foreign and military policy, and as such, it exercised a great deal of influence over the two Consuls. The senate also managed civil administration within the city. For example, only the senate could authorize the appropriation of public monies from the treasury, unless a Consul demanded it. In addition, the senate would try individuals accused of political crimes (such as treason). The senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consultum. While this was officially "advice" from the senate to a magistrate, the senatus consulta were usually obeyed by the magistrates. If a senatus consultum conflicted with a law that was passed by a popular assembly, the law overrode the senatus consultum.

Meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium

), and were usually presided over by a Consul. The presiding Consul began each meeting with a speech on an issue, and then referred the issue to the senators, who discussed the matter by order of seniority. Unimportant matters could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands, while important votes resulted in a physical division of the house, with senators voting by taking a place on either side of the chamber. Any vote was always between a proposal and its negative. Since all meetings had to end by nightfall, a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster

) if he could keep the debate going until nightfall. Any proposed motion could be vetoed by a tribune, and if it was not vetoed, it was then turned into a final senatus consultum. Each senatus consultum was transcribed into a document by the presiding magistrate, and then deposited into the building that housed the treasury.

. There were two types of Roman assembly. The first was the Committee, which was an assembly of all Roman citizens. Here, Roman citizens gathered to enact laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The second type of assembly was the Council, which was an assembly of a specific group of citizens. For example, the "Plebeian Council" was an assembly where plebeians gathered to elect Plebeian magistrates, pass laws that applied only to Plebeians, and try judicial cases concerning Plebeians. A "convention", in contrast, was an unofficial forum for communication, where citizens gathered to debate bills, campaign for office, and decide judicial cases. The voters first assembled into conventions to deliberate, and then they assembled into committees or councils to actually vote. In addition to the Curia (familial groupings), Roman citizens were also organized into "Centuries" (for military purposes) and "Tribes" (for civil purposes). Each gathered into an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Century Assembly

was the assembly of the Centuries, while the Tribal Assembly

was the assembly of the Tribes. Only a bloc of voters (Century, Tribe or Curia), and not the individual electors, cast the formal vote (one vote per bloc) before the assembly. The majority of votes in any Century, Tribe, or Curia decided how that Century, Tribe, or Curia voted.

The Century Assembly was divided into 193 (later 373) Centuries, with each Century belonging to one of three classes: the officer class, the enlisted class, and the unarmed adjuncts. During a vote, the Centuries voted, one at a time, by order of seniority. The president of the Century Assembly was usually a Consul. Only the Century Assembly could elect Consuls

, Praetors and Censors, only it could declare war

, and only it could ratify the results of a census. While it had the power to pass ordinary laws, it rarely did so.

The organization of the Tribal Assembly was much simpler than the Century Assembly, since its organization was based on the thirty-five Tribes. The Tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical divisions (similar to modern electoral districts or constituencies). The president of the Tribal Assembly was usually the Consul, and under his presidency, the assembly elected Quaestors, Curule Aediles

The organization of the Tribal Assembly was much simpler than the Century Assembly, since its organization was based on the thirty-five Tribes. The Tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical divisions (similar to modern electoral districts or constituencies). The president of the Tribal Assembly was usually the Consul, and under his presidency, the assembly elected Quaestors, Curule Aediles

, and Military Tribunes

. While it had the power to pass ordinary laws, it rarely did so. The assembly known as the "Plebeian Council

" was identical to the Tribal Assembly with one key exception: only Plebeians (the commoners) had the power to vote before it. Members of the aristocratic Patrician class were excluded from this assembly. In contrast, both classes were entitled to a vote in the Tribal Assembly. Under the presidency of a Plebeian Tribune

, the Plebeian Council elected Plebeian Tribunes and Plebeian Aediles

, enacted laws called "plebiscites", and presided over judicial cases involving Plebeians.

. Each Roman magistrate was vested with a degree of power. Dictators

had the highest level of power. After the Dictator was the Censor, and then the Consul

, and then the Praetor

, and then the Curule Aedile

, and finally the Quaestor

. Each magistrate could only veto an action that was taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of power. Since Plebeian Tribunes (as well as "Plebeian Aediles") were technically not magistrates, they relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct. If one did not comply with the orders of a Plebeian Tribune, the Tribune could 'interpose the sacrosanctity of his person (intercessio) to physically stop that particular action. Any resistance against the Tribune was considered to be a capital offense.

The most significant constitutional power that a magistrate could hold was that of "Command" (Imperium

), which was held only by Consuls and Praetors. This gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military or otherwise). Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he had to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Since this did create problems for some magistrates, these magistrates occasionally had their command powers extended, which, in effect, allowed them to retain the powers of their office as a Promagistrate

.

The Consul

of the Roman Republic was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Two Consuls were elected every year, and they had supreme power in both civil and military matters. Throughout the year, one Consul was superior in rank to the other Consul, and this ranking flipped every month, between the two Consuls. Praetors administered civil law, presided over the courts, and commanded provincial armies. Another magistrate, the Censor, conducted a census

, during which time they could appoint people to the senate. Aedile

s were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, and were vested with powers over the markets, and over public games and shows. Quaestor

s usually assisted the Consuls in Rome, and the governors in the provinces with financial tasks. Two other magistrates, the Plebeian Tribunes and the Plebeian Aediles

, were considered to be the representatives of the people. Thus, they acted as a popular check over the senate (through their veto powers), and safeguarded the civil liberties of all Roman citizens.

In times of military emergency, a "Roman Dictator" was appointed for a term of six months. Constitutional government dissolved, and the Dictator became the absolute master of the state. The Dictator then appointed a"Master of the Horse" to serve as his most senior lieutenant. Often the Dictator resigned his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved. When the Dictator's term ended, constitutional government was restored. The last ordinary Dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the decree senatus consultum ultimum

In times of military emergency, a "Roman Dictator" was appointed for a term of six months. Constitutional government dissolved, and the Dictator became the absolute master of the state. The Dictator then appointed a"Master of the Horse" to serve as his most senior lieutenant. Often the Dictator resigned his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved. When the Dictator's term ended, constitutional government was restored. The last ordinary Dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the decree senatus consultum ultimum

("ultimate decree of the senate"). This suspended civil government, declared martial law

, and vested the Consuls with Dictatorial powers.

In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus

In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus

was elected Plebeian Tribune, and attempted to enact a law to distribute land to Rome's landless citizens. Tiberius's law was vetoed by an aristocrat named Marcus Octavius

. In an attempt to force Octavius to capitulate, Tiberius tried to turn the mob against Octavius by enacting a blanket veto over all governmental functions, which, in effect, shut down the entire city and precipitated rioting. While the land law was enacted, Tiberius was murdered when he stood for reelection to the tribunate. In 123 BC, Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected Plebeian Tribune. After passing a series of laws which were intended to weaken the senate, Gaius Gracchus

was murdered by his supporters. The people, however, had finally realized how weak the senate had become.

In 88 BC, an aristocratic senator named Lucius Cornelius Sulla

was elected Consul, and soon left for glory in the east. When a Tribune revoked Sulla's command of the war, Sulla brought his army back to Italy, marched on Rome, secured the city, and left for the east again. In 83 BC he returned to Rome, and captured the city a second time. In 82 BC, he made himself Dictator, and then used his status as Dictator to pass a series of constitutional reforms

that were intended to strengthen the senate. In 80 BC he resigned his Dictatorship, and by 78 BC he was dead. While he thought that he had firmly established aristocratic rule, his own career had illustrated the fatal weakness in the constitution: that it was the army, and not the senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state. In 70 BC, the generals Pompey Magnus

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

were both elected Consul, and quickly dismantled Sulla's constitution.

In 62 BC Pompey

returned to Rome from battle in the east, but found the senate refusing to ratify the arrangements that he had made. Thus, when Julius Caesar

returned from his governorship in Spain in 61 BC, he found it easy to make an arrangement with Pompey. Caesar and Pompey, along with Crassus, established a private agreement, known as the First Triumvirate

. Under the agreement, Pompey's arrangements were to be ratified, Crassus was to be promised a future Consulship, and Caesar was to be promised the Consulship in 59 BC, and then the governorship of Gaul

(modern France) immediately afterwards. Caesar became Consul in 59 BC, and, when his term as Consul ended, he took command of four provinces. Eventually, the triumvirate was renewed, and Caesar's term as governor was extended for five years. In 54 BC, violence began sweeping the city. The triumvirate ended in 53 BC when Crassus was killed in battle. In 50 BC, near the end of his term as governor, Caesar demanded the right to stand for election to the Consulship in absentia. Without the protection afforded to him by the Consulship or his army, he could be prosecuted for crimes he had committed. The senate refused Caesar's demand, and in January of 49 BC, the senate passed a resolution which declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July of that year, he would be considered an enemy of the republic. In response, Caesar quickly crossed the Rubicon

with his veteran army, and marched towards Rome. Caesar's rapid advance forced Pompey, the Consuls and the senate to abandon Rome for Greece, and allowed Caesar to enter the city unopposed.

wanted to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed. He assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome's other political institutions. Caesar held the office of Roman Dictator

, and alternated between the Consulship

(the chief-magistracy) and the Proconsul

ship (in effect, a military governorship). In 48 BC, Caesar was given the powers of a Plebeian Tribune, which made his person sacrosanct, gave him the power to veto the Roman Senate

, and allowed him to dominate the legislative process. In 46 BC, Caesar was given the powers of Censor, which he used to fill the senate with his own partisans. Caesar then raised the membership of the senate from 600 to 900, which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made it increasingly subservient to him. Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire

. Since his absence from Rome would limit his ability to install his own Consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates in 43 BC, and all Consuls and Plebeian Tribunes in 42 BC. This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people, to being representatives of the Dictator.

After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, Mark Antony

formed an alliance with Caesar's adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian

. Along with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

, they formed an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate

, and held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution. In effect, there was no constitutional difference between an individual who held the title of Dictator and an individual who held the title of "Triumvir". While the conspirators who had assassinated Caesar were defeated at the Battle of Philippi

in 42 BC, the peace that resulted was only temporary. Antony and Octavian fought against each other in one last battle in 31 BC, at the Battle of Actium

. Antony was defeated, and in 30 BC he committed suicide. In 29 BC, Octavian returned to Rome as the unchallenged master of the state. He eventually enacted a series of constitutional reforms, the most important of which occurred in 27 BC, which overthrew the old republic. The reign of Octavian, whom history remembers as Augustus

, the first Roman Emperor

, marked the dividing line between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

. By the time this process was complete, Rome had completed its transformation from a city-state with a network of dependencies into the capital of a world empire.

Secondary source material

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

(as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

(as was ancient Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

), or a monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

(as was Rome before

Roman Kingdom

The Roman Kingdom was the period of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a monarchical form of government of the city of Rome and its territories....

and, in many respects, after

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

the Republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements, thus creating three separate branches of government. The democratic element took the form of the legislative assemblies, the aristocratic element took the form of the Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

, and the monarchical element took the form of the many term-limited executive magistrates

Executive Magistrates of the Roman Republic

The Executive Magistrates of the Roman Republic were officials of the ancient Roman Republic , elected by the People of Rome...

.

The ultimate source of sovereignty in this ancient republic, as in modern republics, was the demos (people). The People of Rome

SPQR

SPQR is an initialism from a Latin phrase, Senatus Populusque Romanus , referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic, and used as an official emblem of the modern day comune of Rome...

gathered into legislative assemblies to pass laws and to elect executive magistrates. Election to a magisterial office resulted in automatic membership in the Senate (for life, unless impeached

Impeachment

Impeachment is a formal process in which an official is accused of unlawful activity, the outcome of which, depending on the country, may include the removal of that official from office as well as other punishment....

). The Senate managed the day-to-day affairs in Rome, while senators presided over the courts. Executive magistrates enforced the law, and presided over the Senate and the legislative assemblies. A complex set of checks and balances developed between these three branches, so as to minimize the risk of tyranny and corruption, and to maximize the likelihood of good government. However, the separation of powers between these three branches of government was not absolute. Also, there was the frequent usage of several constitutional devices that were out of harmony with the genius of the Roman constitution. A constitutional crisis began in 133 BC, as a result of the struggles between the aristocracy and the common people. This crisis ultimately led to the collapse of the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

and its eventual subversion

Subversion (politics)

Subversion refers to an attempt to transform the established social order, its structures of power, authority, and hierarchy; examples of such structures include the State. In this context, a "subversive" is sometimes called a "traitor" with respect to the government in-power. A subversive is...

into a much more autocratic

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

form of government, the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

Constitutional history (509–133 BC)

At one time, Rome had been ruled by a succession of kings. The Romans believed that this era, that of the Roman KingdomRoman Kingdom

The Roman Kingdom was the period of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a monarchical form of government of the city of Rome and its territories....

, began in 753 BC, and ended in 510 BC. After the monarchy had been overthrown, and the Roman Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

had been founded, the people of Rome began electing two Roman Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

s each year. In 501 BC, the office of "Roman Dictator

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

" was created. In the year 494 BC, the Plebeians (commoners) seceded to the Mons Sacer

Monte Sacro

Monte Sacro is a hill in Rome on the banks of the river Aniene, some kilometres to the north-east of the Campidoglio. It popularly derives its name from being the site of rituals by augurs or haruspices and gives its name to the Monte Sacro quarter....

, and demanded of the Patricians (the aristocrats) the right to elect their own officials. The Patricians duly capitulated, and the Plebeians ended their secession. The Plebeians called these new officials "Plebeian Tribunes

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

", and gave these Tribunes two assistants, called "Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

".

In 449 BC, the Senate promulgated the Twelve Tables

Twelve Tables

The Law of the Twelve Tables was the ancient legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. The Law of the Twelve Tables formed the centrepiece of the constitution of the Roman Republic and the core of the mos maiorum...

as the centerpiece of the Roman Constitution. In 443 BC, the office of "Roman Censor" was created, and in 367 BC, Plebeians were allowed to stand for the Consulship. The opening of the Consulship to the Plebeian class implicitly opened both the Censorship as well as the Dictatorship to Plebeians. In 366 BC, in an effort by the Patricians to reassert their influence over the magisterial offices, two new offices were created. While these two offices, the Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

ship and the Curule Aedileship

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

, were at first open only to Patricians, within a generation, they were open to Plebeians as well.

Beginning around the year 350 BC, the senators and the Plebeian Tribunes began to grow closer. The senate began giving Tribunes more power, and, unsurprisingly, the Tribunes began to feel indebted to the senate. As the Tribunes and the senators grew closer, Plebeian senators began to routinely secure the office of Tribune for members of their own families. Also around the year 350 BC, the Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

(popular assembly) enacted a significant law (the "Ovinian Law") which transferred, from the Consuls to the Censors, the power to appoint new senators. This law also required the Censors to appoint any newly elected magistrate to the senate, which probably resulted in a significant increase in the number of Plebeian senators. This, along with the closeness between the Plebeian Tribunes and the senate, helped to facilitate the creation of a new Plebeian aristocracy. This new Plebeian aristocracy soon merged with the old Patrician aristocracy, creating a combined "Patricio-Plebeian" aristocracy. The old aristocracy existed through the force of law, because only Patricians had been allowed to stand for high office. Now, however, the new aristocracy existed due to the organization of society, and as such, this order could only be overthrown through a revolution.

In 287 BC, the Plebeians seceded to the Janiculum hill

Janiculum

The Janiculum is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although the second-tallest hill in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the proverbial Seven Hills of Rome, being west of the Tiber and outside the boundaries of the ancient city.-Sights:The Janiculum is one of the...

. To end the secession, a law (the "Hortensian Law") was passed, which ended the requirement that the Patrician senators consent before a bill could be brought before the Plebeian Council for a vote. This was not the first law to require that an act of the Plebeian Council have the full force of law (over both Plebeians and Patricians), since the Plebeian Council had acquired this power in 449 BC. The ultimate significance of this law was in the fact that it robbed the Patricians of their final weapon over the Plebeians. The result was that the ultimate control over the state fell, not onto the shoulders of democracy, but onto the shoulders of the new Patricio-Plebeian aristocracy. The Hortensian Law resolved the last great political question of the earlier era, and as such, no important political changes occurred over the next 150 years (between 287 BC and 133 BC). The critical laws of this era were still enacted by the senate. In effect, the democracy was satisfied with the possession of power, but did not care to actually use it.

Senate

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. The Roman senate's authority derived from Roman precedent, custom, and the high caliber of the senators. The senate's principal role was as an advisory council to the two Roman Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

s on matters of foreign and military policy, and as such, it exercised a great deal of influence over the two Consuls. The senate also managed civil administration within the city. For example, only the senate could authorize the appropriation of public monies from the treasury, unless a Consul demanded it. In addition, the senate would try individuals accused of political crimes (such as treason). The senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consultum. While this was officially "advice" from the senate to a magistrate, the senatus consulta were usually obeyed by the magistrates. If a senatus consultum conflicted with a law that was passed by a popular assembly, the law overrode the senatus consultum.

Meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium

Pomerium

The pomerium or pomoerium , was the sacred boundary of the city of Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within the pomerium; everything beyond it was simply territory belonging to Rome.-Location and extensions:Tradition maintained that it was the original line ploughed by Romulus around the...

), and were usually presided over by a Consul. The presiding Consul began each meeting with a speech on an issue, and then referred the issue to the senators, who discussed the matter by order of seniority. Unimportant matters could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands, while important votes resulted in a physical division of the house, with senators voting by taking a place on either side of the chamber. Any vote was always between a proposal and its negative. Since all meetings had to end by nightfall, a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster

Filibuster

A filibuster is a type of parliamentary procedure. Specifically, it is the right of an individual to extend debate, allowing a lone member to delay or entirely prevent a vote on a given proposal...

) if he could keep the debate going until nightfall. Any proposed motion could be vetoed by a tribune, and if it was not vetoed, it was then turned into a final senatus consultum. Each senatus consultum was transcribed into a document by the presiding magistrate, and then deposited into the building that housed the treasury.

Legislative Assemblies

The Roman assemblies were political institutions in the Roman RepublicRoman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. There were two types of Roman assembly. The first was the Committee, which was an assembly of all Roman citizens. Here, Roman citizens gathered to enact laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The second type of assembly was the Council, which was an assembly of a specific group of citizens. For example, the "Plebeian Council" was an assembly where plebeians gathered to elect Plebeian magistrates, pass laws that applied only to Plebeians, and try judicial cases concerning Plebeians. A "convention", in contrast, was an unofficial forum for communication, where citizens gathered to debate bills, campaign for office, and decide judicial cases. The voters first assembled into conventions to deliberate, and then they assembled into committees or councils to actually vote. In addition to the Curia (familial groupings), Roman citizens were also organized into "Centuries" (for military purposes) and "Tribes" (for civil purposes). Each gathered into an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Century Assembly

Century Assembly

The Century Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial...

was the assembly of the Centuries, while the Tribal Assembly

Tribal Assembly

The Tribal Assembly of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman citizens. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of thirty-five Tribes: Four Tribes encompassed citizens inside the city of Rome, while the other thirty-one Tribes encompassed...

was the assembly of the Tribes. Only a bloc of voters (Century, Tribe or Curia), and not the individual electors, cast the formal vote (one vote per bloc) before the assembly. The majority of votes in any Century, Tribe, or Curia decided how that Century, Tribe, or Curia voted.

The Century Assembly was divided into 193 (later 373) Centuries, with each Century belonging to one of three classes: the officer class, the enlisted class, and the unarmed adjuncts. During a vote, the Centuries voted, one at a time, by order of seniority. The president of the Century Assembly was usually a Consul. Only the Century Assembly could elect Consuls

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

, Praetors and Censors, only it could declare war

Declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one nation goes to war against another. The declaration is a performative speech act by an authorized party of a national government in order to create a state of war between two or more states.The legality of who is competent to declare war varies...

, and only it could ratify the results of a census. While it had the power to pass ordinary laws, it rarely did so.

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

, and Military Tribunes

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

. While it had the power to pass ordinary laws, it rarely did so. The assembly known as the "Plebeian Council

Plebeian Council

The Concilium Plebis — known in English as the Plebeian Council or People's Assembly — was the principal popular assembly of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative assembly, through which the plebeians could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian...

" was identical to the Tribal Assembly with one key exception: only Plebeians (the commoners) had the power to vote before it. Members of the aristocratic Patrician class were excluded from this assembly. In contrast, both classes were entitled to a vote in the Tribal Assembly. Under the presidency of a Plebeian Tribune

Tribune

Tribune was a title shared by elected officials in the Roman Republic. Tribunes had the power to convene the Plebeian Council and to act as its president, which also gave them the right to propose legislation before it. They were sacrosanct, in the sense that any assault on their person was...

, the Plebeian Council elected Plebeian Tribunes and Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

, enacted laws called "plebiscites", and presided over judicial cases involving Plebeians.

Executive Magistrates

The Roman Magistrates were elected officials of the Roman RepublicRoman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. Each Roman magistrate was vested with a degree of power. Dictators

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

had the highest level of power. After the Dictator was the Censor, and then the Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

, and then the Praetor

Praetor

Praetor was a title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to men acting in one of two official capacities: the commander of an army, usually in the field, or the named commander before mustering the army; and an elected magistratus assigned varied duties...

, and then the Curule Aedile

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

, and finally the Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

. Each magistrate could only veto an action that was taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of power. Since Plebeian Tribunes (as well as "Plebeian Aediles") were technically not magistrates, they relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct. If one did not comply with the orders of a Plebeian Tribune, the Tribune could 'interpose the sacrosanctity of his person (intercessio) to physically stop that particular action. Any resistance against the Tribune was considered to be a capital offense.

The most significant constitutional power that a magistrate could hold was that of "Command" (Imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

), which was held only by Consuls and Praetors. This gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military or otherwise). Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he had to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Since this did create problems for some magistrates, these magistrates occasionally had their command powers extended, which, in effect, allowed them to retain the powers of their office as a Promagistrate

Promagistrate

A promagistrate is a person who acts in and with the authority and capacity of a magistrate, but without holding a magisterial office. A legal innovation of the Roman Republic, the promagistracy was invented in order to provide Rome with governors of overseas territories instead of having to elect...

.

The Consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

of the Roman Republic was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Two Consuls were elected every year, and they had supreme power in both civil and military matters. Throughout the year, one Consul was superior in rank to the other Consul, and this ranking flipped every month, between the two Consuls. Praetors administered civil law, presided over the courts, and commanded provincial armies. Another magistrate, the Censor, conducted a census

Census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring and recording information about the members of a given population. It is a regularly occurring and official count of a particular population. The term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common...

, during which time they could appoint people to the senate. Aedile

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

s were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, and were vested with powers over the markets, and over public games and shows. Quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

s usually assisted the Consuls in Rome, and the governors in the provinces with financial tasks. Two other magistrates, the Plebeian Tribunes and the Plebeian Aediles

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

, were considered to be the representatives of the people. Thus, they acted as a popular check over the senate (through their veto powers), and safeguarded the civil liberties of all Roman citizens.

Senatus consultum ultimum

Senatus consultum ultimum , more properly senatus consultum de re publica defendenda is the modern term given to a decree of the Roman Senate during the late Roman Republic passed in times of emergency...

("ultimate decree of the senate"). This suspended civil government, declared martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

, and vested the Consuls with Dictatorial powers.

Constitutional instability (133–49 BC)

By the middle of the 2nd century BC, the economic situation for the average Plebeian had declined significantly. The long military campaigns had forced citizens to leave their farms to fight, only to return to farms that had fallen into disrepair. The landed aristocracy began buying bankrupted farms at discounted prices, creating a situation that made it impossible for the average farmer to operate his farm at a profit. Masses of unemployed Plebeians soon began to flood into Rome, and thus into the ranks of the legislative assemblies, where their economic status usually led them to vote for the candidate who offered the most for them. A new culture of dependency was emerging, which would look to any populist leader for relief.

Gracchi

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, were Roman Plebian nobiles who both served as tribunes in 2nd century BC. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. For this legislation and their membership in the...

was elected Plebeian Tribune, and attempted to enact a law to distribute land to Rome's landless citizens. Tiberius's law was vetoed by an aristocrat named Marcus Octavius

Marcus Octavius

Marcus Octavius was a Roman tribune and a major rival of Tiberius Gracchus. A serious and discreet person, he earned himself a reputation as an influential orator. Though originally close friends, Octavius became alarmed by Gracchus's populist agenda and, at the behest of the Roman senate,...

. In an attempt to force Octavius to capitulate, Tiberius tried to turn the mob against Octavius by enacting a blanket veto over all governmental functions, which, in effect, shut down the entire city and precipitated rioting. While the land law was enacted, Tiberius was murdered when he stood for reelection to the tribunate. In 123 BC, Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected Plebeian Tribune. After passing a series of laws which were intended to weaken the senate, Gaius Gracchus

Gracchi

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, were Roman Plebian nobiles who both served as tribunes in 2nd century BC. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians. For this legislation and their membership in the...

was murdered by his supporters. The people, however, had finally realized how weak the senate had become.

In 88 BC, an aristocratic senator named Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

was elected Consul, and soon left for glory in the east. When a Tribune revoked Sulla's command of the war, Sulla brought his army back to Italy, marched on Rome, secured the city, and left for the east again. In 83 BC he returned to Rome, and captured the city a second time. In 82 BC, he made himself Dictator, and then used his status as Dictator to pass a series of constitutional reforms

Constitutional Reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla

The Constitutional Reforms of Lucius Cornelius Sulla were a series of laws that were enacted by the Roman Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla between 82 and 80 BC, which reformed the Constitution of the Roman Republic. In the decades before Sulla had become Dictator, a series of political developments...

that were intended to strengthen the senate. In 80 BC he resigned his Dictatorship, and by 78 BC he was dead. While he thought that he had firmly established aristocratic rule, his own career had illustrated the fatal weakness in the constitution: that it was the army, and not the senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state. In 70 BC, the generals Pompey Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and politician who commanded the right wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the...

were both elected Consul, and quickly dismantled Sulla's constitution.

In 62 BC Pompey

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

returned to Rome from battle in the east, but found the senate refusing to ratify the arrangements that he had made. Thus, when Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

returned from his governorship in Spain in 61 BC, he found it easy to make an arrangement with Pompey. Caesar and Pompey, along with Crassus, established a private agreement, known as the First Triumvirate

First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was the political alliance of Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Unlike the Second Triumvirate, the First Triumvirate had no official status whatsoever; its overwhelming power in the Roman Republic was strictly unofficial influence, and...

. Under the agreement, Pompey's arrangements were to be ratified, Crassus was to be promised a future Consulship, and Caesar was to be promised the Consulship in 59 BC, and then the governorship of Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

(modern France) immediately afterwards. Caesar became Consul in 59 BC, and, when his term as Consul ended, he took command of four provinces. Eventually, the triumvirate was renewed, and Caesar's term as governor was extended for five years. In 54 BC, violence began sweeping the city. The triumvirate ended in 53 BC when Crassus was killed in battle. In 50 BC, near the end of his term as governor, Caesar demanded the right to stand for election to the Consulship in absentia. Without the protection afforded to him by the Consulship or his army, he could be prosecuted for crimes he had committed. The senate refused Caesar's demand, and in January of 49 BC, the senate passed a resolution which declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July of that year, he would be considered an enemy of the republic. In response, Caesar quickly crossed the Rubicon

Rubicon

The Rubicon is a shallow river in northeastern Italy, about 80 kilometres long, running from the Apennine Mountains to the Adriatic Sea through the southern Emilia-Romagna region, between the towns of Rimini and Cesena. The Latin word rubico comes from the adjective "rubeus", meaning "red"...

with his veteran army, and marched towards Rome. Caesar's rapid advance forced Pompey, the Consuls and the senate to abandon Rome for Greece, and allowed Caesar to enter the city unopposed.

The transition from Republic to Empire (49–27 BC)

By 48 BC, after having defeated the last of his major enemies, Julius CaesarJulius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

wanted to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed. He assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome's other political institutions. Caesar held the office of Roman Dictator

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

, and alternated between the Consulship

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

(the chief-magistracy) and the Proconsul

Proconsul

A proconsul was a governor of a province in the Roman Republic appointed for one year by the senate. In modern usage, the title has been used for a person from one country ruling another country or bluntly interfering in another country's internal affairs.-Ancient Rome:In the Roman Republic, a...

ship (in effect, a military governorship). In 48 BC, Caesar was given the powers of a Plebeian Tribune, which made his person sacrosanct, gave him the power to veto the Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

, and allowed him to dominate the legislative process. In 46 BC, Caesar was given the powers of Censor, which he used to fill the senate with his own partisans. Caesar then raised the membership of the senate from 600 to 900, which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made it increasingly subservient to him. Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire

Parthia

Parthia is a region of north-eastern Iran, best known for having been the political and cultural base of the Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire....

. Since his absence from Rome would limit his ability to install his own Consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates in 43 BC, and all Consuls and Plebeian Tribunes in 42 BC. This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people, to being representatives of the Dictator.

After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, Mark Antony

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius , known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general. As a military commander and administrator, he was an important supporter and loyal friend of his mother's cousin Julius Caesar...

formed an alliance with Caesar's adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

. Along with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (triumvir)

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus , was a Roman patrician who rose to become a member of the Second Triumvirate and Pontifex Maximus. His father, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, had been involved in a rebellion against the Roman Republic.Lepidus was among Julius Caesar's greatest supporters...

, they formed an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate

Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate is the name historians give to the official political alliance of Octavius , Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, and Mark Antony, formed on 26 November 43 BC with the enactment of the Lex Titia, the adoption of which marked the end of the Roman Republic...

, and held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution. In effect, there was no constitutional difference between an individual who held the title of Dictator and an individual who held the title of "Triumvir". While the conspirators who had assassinated Caesar were defeated at the Battle of Philippi

Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian and the forces of Julius Caesar's assassins Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus in 42 BC, at Philippi in Macedonia...

in 42 BC, the peace that resulted was only temporary. Antony and Octavian fought against each other in one last battle in 31 BC, at the Battle of Actium

Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was the decisive confrontation of the Final War of the Roman Republic. It was fought between the forces of Octavian and the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC, on the Ionian Sea near the city of Actium, at the Roman...

. Antony was defeated, and in 30 BC he committed suicide. In 29 BC, Octavian returned to Rome as the unchallenged master of the state. He eventually enacted a series of constitutional reforms, the most important of which occurred in 27 BC, which overthrew the old republic. The reign of Octavian, whom history remembers as Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

, the first Roman Emperor

Roman Emperor

The Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

, marked the dividing line between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. By the time this process was complete, Rome had completed its transformation from a city-state with a network of dependencies into the capital of a world empire.

See also

Further reading

Primary sources- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius

Secondary source material