Century Assembly

Encyclopedia

The Century Assembly of the Roman Republic

was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The majority of votes in any Century decided how that Century voted. Each Century received one vote, regardless of how many electors each Century held. Once a majority of Centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting ended, and the matter was decided. Only the Century Assembly could declare war or elect the highest-ranking Roman Magistrates

: "'Consuls

", "Praetors" and "Censors". The Century Assembly could also pass a law that granted constitutional command authority, or "Imperium

", to Consuls and Praetors (the lex de imperio or "Law on Imperium"), and Censorial powers to Censors (the lex de potestate censoria or "Law on Censorial Powers"). In addition, the Century Assembly served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases (in particular, cases involving capital punishment), and ratified the results of a Census.

Since the Romans used a form of direct democracy, citizens, and not elected representatives, voted before each assembly. As such, the citizen-electors had no power, other than the power to cast a vote. Each assembly was presided over by a single Roman Magistrate, and as such, it was the presiding magistrate who made all decisions on matters of procedure and legality. Ultimately, the presiding magistrate's power over the assembly was nearly absolute. The only check on that power came in the form of vetoes handed down by other magistrates. Any decision made by a presiding magistrate could be vetoed by a magistrate known as a "Plebeian Tribune". In addition, decisions made by presiding magistrates could also be vetoed by higher-ranking magistrates.

, two primary types of assembly were used to vote on legislative, electoral, and judicial matters. The first was the Committee (comitia, literally "going together" or "meeting place"). The Century Assembly was a Committee. Committees were assemblies of all citizens, and were used for official purposes, such as for the enactment of laws. Acts of a Committee applied to all of the members of that Committee. The second type of assembly was the Council (concilium), which was a forum where specific groups of citizens met for official purposes. In contrast, the Convention (conventio, literally "coming together") was an unofficial forum for communication. Conventions were simply forums where Romans met for specific unofficial purposes, such as, for example, to hear a political speech. Private citizens who did not hold political office could only speak before a Convention, and not before a Committee or a Council. Conventions were simply meetings, and no legal or legislative decisions could be made in one. Voters always assembled first into Conventions to hear debates and conduct other business before voting, and then into Committees or Councils to actually vote.

A notice always had to be given several days before the assembly was to actually vote. For elections, at least three market-days (often more than seventeen actual days) had to pass between the announcement of the election, and the actual election. During this time period (the trinundinum), the candidates interacted with the electorate, and no legislation could be proposed or voted upon. In 98 BC, a law was passed (the lex Caecilia Didia) which required a similar three market-day interval to pass between the proposal of a law and the vote on that law. During criminal trials, the assembly's presiding magistrate had to give a notice (diem dicere) to the accused person on the first day of the investigation (anquisito). At the end of each day, the magistrate had to give another notice to the accused person (diem prodicere), which informed him of the status of the investigation. After the investigation was complete, a three market-day interval had to elapse before a final vote could be taken with respect to conviction or acquittal.

A notice always had to be given several days before the assembly was to actually vote. For elections, at least three market-days (often more than seventeen actual days) had to pass between the announcement of the election, and the actual election. During this time period (the trinundinum), the candidates interacted with the electorate, and no legislation could be proposed or voted upon. In 98 BC, a law was passed (the lex Caecilia Didia) which required a similar three market-day interval to pass between the proposal of a law and the vote on that law. During criminal trials, the assembly's presiding magistrate had to give a notice (diem dicere) to the accused person on the first day of the investigation (anquisito). At the end of each day, the magistrate had to give another notice to the accused person (diem prodicere), which informed him of the status of the investigation. After the investigation was complete, a three market-day interval had to elapse before a final vote could be taken with respect to conviction or acquittal.

Only one assembly could operate at any given point in time, and any session already underway could be dissolved if a magistrate "called away" (avocare) the electors. In addition to the presiding magistrate, several additional magistrates were often present to act as assistants. They were available to help resolve procedural disputes, and to provide a mechanism through which electors could appeal decisions of the presiding magistrate. There were also religious officials (known as Augur

s) either in attendance or on-call, who would be available to help interpret any signs from the Gods (omens), since the Romans believed that the Gods let their approval or disapproval with proposed actions be known. In addition, a preliminary search for omens (auspices) was conducted by the presiding magistrate the night before any meeting. On several known occasions, presiding magistrates used the claim of unfavorable omens as an excuse to suspend a session that was not going the way they wanted.

On the day of the vote, the electors first assembled into their Conventions for debate and campaigning. In the Conventions, the electors were not sorted into their respective Centuries. Speeches from private citizens were only heard if the issue to be voted upon was a legislative or judicial matter, and even then, only if the citizen received permission from the presiding magistrate. If the purpose of the ultimate vote was for an election, no speeches from private citizens were heard, and instead, the candidates for office used the Convention to campaign. During the Convention, the bill to be voted upon was read to the assembly by an officer known as a "Herald". A Plebeian Tribune could use his veto against pending legislation up until this point, but not after.

The electors were then told to break up the Convention ("depart to your separate groups", or discedite, quirites), and assemble into their formal Century. The electors assembled behind a fenced off area and voted by placing a pebble or written ballot into an appropriate jar. The baskets (cistae) that held the votes were watched by specific officers (the custodes), who then counted the ballots, and reported the results to the presiding magistrate. The majority of votes in any Century decided how that Century voted. If the process was not complete by nightfall, the electors were dismissed without having reached a decision, and the process had to begin again the next day.

"), wore a purple-bordered toga

, and was accompanied by bodyguards called lictors. Each lictor carried the symbol of state power, the fasces

, which was a bundle of white birch rods, tied together with a red leather ribbon into a cylinder, and with a blade on the side, projecting from the bundle. While the voters in this assembly wore white undecorated togas and were unarmed, they were still soldiers, and as such they could not meet inside of the physical boundary of the city of Rome (the pomerium). Because of this, as well as the large size of the assembly (as many as 373 centuries), the assembly often met on the Field of Mars

(Latin: Campus Martius), which was a large field located right outside of the city wall. The president of the Century Assembly was usually a Consul (although sometimes a Praetor). Only Consuls (the highest-ranking of all Roman Magistrates) could preside over the Century Assembly during elections because the higher-ranking Consuls were always elected together with the lower-ranking Praetors. Consuls and Praetors were usually elected in July, and took office in January. Two Consuls, and at least six Praetors, were elected each year for an annual term that began in January and ended in December. In contrast, two Censors were elected every five years. Once every five years, after the new Consuls for the year took office, they presided over the Century Assembly as it elected the two Censors.

, less than a century before the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC. As such, the original design of the Century Assembly was known as the "Servian Organization". Under this organization, the assembly was supposedly designed to mirror the Roman army during the time of the Roman Kingdom

. The Roman army

was based on units called "Centuries

", which were comparable to Companies

in a modern army. While Centuries in the Roman army always consisted of about one hundred soldiers, Centuries in the Century Assembly usually did not. This was because the property qualifications for membership in a voting Century did not change over time, as property qualifications for membership in a military Century did. Soldiers in the Roman army were classified on the basis of the amount of property that they owned, and as such, soldiers with more property outranked soldiers with less property. Since the wealthy soldiers were divided into more Centuries in the early Roman army, the wealthy soldiers were also divided into more Centuries in the Century Assembly. Thus, the wealthy soldiers, who were fewer in number and had more to lose, had a greater overall influence.

The 193 Centuries in the assembly under the Servian Organization were each divided into one of three different grades: the officer class (the cavalry or equites), the enlisted class (infantry or pedites) and the miscellaneous class (mostly unarmed adjuncts). The officer class was grouped into eighteen Centuries, six of which (the sex suffragia) were composed exclusively of Patricians (Roman aristocrats). The enlisted class was grouped into 170 Centuries. Most enlisted individuals (those aged seventeen to forty-six) were grouped into eighty-five Centuries of "junior soldiers" (iuniores or "young men"). The relatively limited number of enlisted soldiers who were aged forty-six to sixty were grouped into eighty-five Centuries of "senior soldiers" (seniores or "old men"). The result of this arrangement was that the votes of the older soldiers carried more weight than did the votes of the numerically greater younger soldiers. According to Cicero

, the Consul of 63 BC, this design was intentional so that the decisions of the assembly were more in line with the will of the more experienced soldiers who arguably had more to lose. The 170 Centuries of enlisted soldiers were divided into five classes, each with a separate property requirement: The first class consisted of soldiers with heavy armor, the lower classes had successively less armor, and the soldiers of the fifth class had nothing more than slings and stones. Each of the five property classes were divided equally between Centuries of younger soldiers and Centuries of older soldiers. The first class of enlisted soldiers consisted of eighty Centuries, classes two through four consisted of twenty Centuries each, and class five consisted of thirty Centuries. The unarmed soldiers were divided into the final five Centuries: four of these Centuries were composed of artisans and musicians (such as trumpeters and horn blowers), while the fifth Century (the proletarii) consisted of people with little or no property.

During a vote, all of the Centuries of one class had to vote before the Centuries of the next lower class could vote. The seven classes voted by order of seniority: first the officer class, then the first enlisted class, then the second enlisted class, then the third enlisted class, then the fourth enlisted class, then the fifth enlisted class, and then finally the unarmed Centuries. When a measure received a majority of the vote, the voting ended, and as such, many lower ranking Centuries rarely if ever had a chance to actually vote.

During a vote, all of the Centuries of one class had to vote before the Centuries of the next lower class could vote. The seven classes voted by order of seniority: first the officer class, then the first enlisted class, then the second enlisted class, then the third enlisted class, then the fourth enlisted class, then the fifth enlisted class, and then finally the unarmed Centuries. When a measure received a majority of the vote, the voting ended, and as such, many lower ranking Centuries rarely if ever had a chance to actually vote.

and Gaius Aurelius Cotta, in order to give more weight to the lower ranking Centuries, and thus make the assembly less aristocratic. Under the old system, there were a total of 193 Centuries, while under the new system, there were a total of 373 Centuries. Under the new system, the thirty-five Tribes were each divided into ten Centuries: five of older soldiers, and five of younger soldiers. Of each of these five Centuries, one was assigned to one of the five property classes. Therefore, each Tribe had two Centuries (one of older soldiers and one of younger soldiers) allocated to each of the five property classes. In addition, the property requirements for each of the five classes were probably raised. In total, this resulted in 350 Centuries of enlisted soldiers. The same eighteen Centuries of officers, and the same five Centuries of unarmed soldiers, were also included in the redesign. Now, majorities usually could not be reached until the third class of enlisted Centuries had begun voting.

Since the lowest ranking Century in the Century Assembly, the fifth unarmed Century (the proletarii), was always the last Century to vote, it never had any real influence on elections, and as such, it was so poorly regarded that it was all but ignored during the Census. In 107 BC, in response to high unemployment and a severe manpower shortage in the army, the general and Consul Gaius Marius

reformed the organization of the army

, and allowed individuals with no property to enlist. As a consequence of these reforms, this fifth unarmed Century came to encompass almost the entire Roman army. This mass disenfranchisement of most of the soldiers in the army played an important role in the chaos that led to the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC.

During his dictatorship

from 82 BC until 80 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

restored the old Servian organization to this assembly. This reform was one in a slate of constitutional reforms enacted by Sulla as a consequence of the recent Civil War between his supporters and those of the politically-populist then-former Consul Gaius Marius

. His reforms were intended to reassert aristocratic control over the constitution, and thus prevent the emergence of another Marius. Sulla died in 78 BC, and in 70 BC, the Consuls Pompey Magnus

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

repealed Sulla's constitutional reforms, including his restoration of the Servian Organization to this assembly. They restored the less aristocratic organization (from 241 BC by the Censors Marcus Fabius Buteo

and Gaius Aurelius Cotta). The organization of the Century Assembly was not changed again until its powers were all transferred to the Roman Senate

by the first Roman Emperor

, Augustus

, after the fall of the Roman Republic in 27

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

was the democratic assembly of Roman soldiers. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of Centuries for military purposes. The Centuries gathered into the Century Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The majority of votes in any Century decided how that Century voted. Each Century received one vote, regardless of how many electors each Century held. Once a majority of Centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting ended, and the matter was decided. Only the Century Assembly could declare war or elect the highest-ranking Roman Magistrates

Roman Magistrates

The Roman Magistrates were elected officials in Ancient Rome. During the period of the Roman Kingdom, the King of Rome was the principal executive magistrate. His power, in practice, was absolute. He was the chief priest, lawgiver, judge, and the sole commander of the army...

: "'Consuls

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

", "Praetors" and "Censors". The Century Assembly could also pass a law that granted constitutional command authority, or "Imperium

Imperium

Imperium is a Latin word which, in a broad sense, translates roughly as 'power to command'. In ancient Rome, different kinds of power or authority were distinguished by different terms. Imperium, referred to the sovereignty of the state over the individual...

", to Consuls and Praetors (the lex de imperio or "Law on Imperium"), and Censorial powers to Censors (the lex de potestate censoria or "Law on Censorial Powers"). In addition, the Century Assembly served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases (in particular, cases involving capital punishment), and ratified the results of a Census.

Since the Romans used a form of direct democracy, citizens, and not elected representatives, voted before each assembly. As such, the citizen-electors had no power, other than the power to cast a vote. Each assembly was presided over by a single Roman Magistrate, and as such, it was the presiding magistrate who made all decisions on matters of procedure and legality. Ultimately, the presiding magistrate's power over the assembly was nearly absolute. The only check on that power came in the form of vetoes handed down by other magistrates. Any decision made by a presiding magistrate could be vetoed by a magistrate known as a "Plebeian Tribune". In addition, decisions made by presiding magistrates could also be vetoed by higher-ranking magistrates.

Assembly procedure

In the Roman system of direct democracyDirect democracy

Direct democracy is a form of government in which people vote on policy initiatives directly, as opposed to a representative democracy in which people vote for representatives who then vote on policy initiatives. Direct democracy is classically termed "pure democracy"...

, two primary types of assembly were used to vote on legislative, electoral, and judicial matters. The first was the Committee (comitia, literally "going together" or "meeting place"). The Century Assembly was a Committee. Committees were assemblies of all citizens, and were used for official purposes, such as for the enactment of laws. Acts of a Committee applied to all of the members of that Committee. The second type of assembly was the Council (concilium), which was a forum where specific groups of citizens met for official purposes. In contrast, the Convention (conventio, literally "coming together") was an unofficial forum for communication. Conventions were simply forums where Romans met for specific unofficial purposes, such as, for example, to hear a political speech. Private citizens who did not hold political office could only speak before a Convention, and not before a Committee or a Council. Conventions were simply meetings, and no legal or legislative decisions could be made in one. Voters always assembled first into Conventions to hear debates and conduct other business before voting, and then into Committees or Councils to actually vote.

Only one assembly could operate at any given point in time, and any session already underway could be dissolved if a magistrate "called away" (avocare) the electors. In addition to the presiding magistrate, several additional magistrates were often present to act as assistants. They were available to help resolve procedural disputes, and to provide a mechanism through which electors could appeal decisions of the presiding magistrate. There were also religious officials (known as Augur

Augur

The augur was a priest and official in the classical world, especially ancient Rome and Etruria. His main role was to interpret the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds: whether they are flying in groups/alone, what noises they make as they fly, direction of flight and what kind of...

s) either in attendance or on-call, who would be available to help interpret any signs from the Gods (omens), since the Romans believed that the Gods let their approval or disapproval with proposed actions be known. In addition, a preliminary search for omens (auspices) was conducted by the presiding magistrate the night before any meeting. On several known occasions, presiding magistrates used the claim of unfavorable omens as an excuse to suspend a session that was not going the way they wanted.

On the day of the vote, the electors first assembled into their Conventions for debate and campaigning. In the Conventions, the electors were not sorted into their respective Centuries. Speeches from private citizens were only heard if the issue to be voted upon was a legislative or judicial matter, and even then, only if the citizen received permission from the presiding magistrate. If the purpose of the ultimate vote was for an election, no speeches from private citizens were heard, and instead, the candidates for office used the Convention to campaign. During the Convention, the bill to be voted upon was read to the assembly by an officer known as a "Herald". A Plebeian Tribune could use his veto against pending legislation up until this point, but not after.

The electors were then told to break up the Convention ("depart to your separate groups", or discedite, quirites), and assemble into their formal Century. The electors assembled behind a fenced off area and voted by placing a pebble or written ballot into an appropriate jar. The baskets (cistae) that held the votes were watched by specific officers (the custodes), who then counted the ballots, and reported the results to the presiding magistrate. The majority of votes in any Century decided how that Century voted. If the process was not complete by nightfall, the electors were dismissed without having reached a decision, and the process had to begin again the next day.

The presiding magistrate and elections

The presiding magistrate sat on a special chair (the "curule chairCurule chair

In the Roman Republic, and later the Empire, the curule seat was the chair upon which senior magistrates or promagistrates owning imperium were entitled to sit, including dictators, masters of the horse, consuls, praetors, censors, and the curule aediles...

"), wore a purple-bordered toga

Toga

The toga, a distinctive garment of Ancient Rome, was a cloth of perhaps 20 ft in length which was wrapped around the body and was generally worn over a tunic. The toga was made of wool, and the tunic under it often was made of linen. After the 2nd century BC, the toga was a garment worn...

, and was accompanied by bodyguards called lictors. Each lictor carried the symbol of state power, the fasces

Fasces

Fasces are a bundle of wooden sticks with an axe blade emerging from the center, which is an image that traditionally symbolizes summary power and jurisdiction, and/or "strength through unity"...

, which was a bundle of white birch rods, tied together with a red leather ribbon into a cylinder, and with a blade on the side, projecting from the bundle. While the voters in this assembly wore white undecorated togas and were unarmed, they were still soldiers, and as such they could not meet inside of the physical boundary of the city of Rome (the pomerium). Because of this, as well as the large size of the assembly (as many as 373 centuries), the assembly often met on the Field of Mars

Field of Mars

The Field of Mars was an area of the ancient city of Rome, the Campus Martius.Field of Mars may also refer to:*Field of Mars , An large public greenplace in Paris...

(Latin: Campus Martius), which was a large field located right outside of the city wall. The president of the Century Assembly was usually a Consul (although sometimes a Praetor). Only Consuls (the highest-ranking of all Roman Magistrates) could preside over the Century Assembly during elections because the higher-ranking Consuls were always elected together with the lower-ranking Praetors. Consuls and Praetors were usually elected in July, and took office in January. Two Consuls, and at least six Praetors, were elected each year for an annual term that began in January and ended in December. In contrast, two Censors were elected every five years. Once every five years, after the new Consuls for the year took office, they presided over the Century Assembly as it elected the two Censors.

The Servian Organization of the Century Assembly (509-107 BC)

The Century Assembly was supposedly founded by the legendary Roman King Servius TulliusServius Tullius

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of ancient Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned 578-535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome's first Etruscan king, who was assassinated in 579 BC...

, less than a century before the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC. As such, the original design of the Century Assembly was known as the "Servian Organization". Under this organization, the assembly was supposedly designed to mirror the Roman army during the time of the Roman Kingdom

Roman Kingdom

The Roman Kingdom was the period of the ancient Roman civilization characterized by a monarchical form of government of the city of Rome and its territories....

. The Roman army

Roman army

The Roman army is the generic term for the terrestrial armed forces deployed by the kingdom of Rome , the Roman Republic , the Roman Empire and its successor, the Byzantine empire...

was based on units called "Centuries

Centuria

Centuria is a Latin substantive from the stem centum , denoting units consisting of 100 men. It also denotes a Roman unit of land area: 1 centuria = 100 heredia...

", which were comparable to Companies

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

in a modern army. While Centuries in the Roman army always consisted of about one hundred soldiers, Centuries in the Century Assembly usually did not. This was because the property qualifications for membership in a voting Century did not change over time, as property qualifications for membership in a military Century did. Soldiers in the Roman army were classified on the basis of the amount of property that they owned, and as such, soldiers with more property outranked soldiers with less property. Since the wealthy soldiers were divided into more Centuries in the early Roman army, the wealthy soldiers were also divided into more Centuries in the Century Assembly. Thus, the wealthy soldiers, who were fewer in number and had more to lose, had a greater overall influence.

The 193 Centuries in the assembly under the Servian Organization were each divided into one of three different grades: the officer class (the cavalry or equites), the enlisted class (infantry or pedites) and the miscellaneous class (mostly unarmed adjuncts). The officer class was grouped into eighteen Centuries, six of which (the sex suffragia) were composed exclusively of Patricians (Roman aristocrats). The enlisted class was grouped into 170 Centuries. Most enlisted individuals (those aged seventeen to forty-six) were grouped into eighty-five Centuries of "junior soldiers" (iuniores or "young men"). The relatively limited number of enlisted soldiers who were aged forty-six to sixty were grouped into eighty-five Centuries of "senior soldiers" (seniores or "old men"). The result of this arrangement was that the votes of the older soldiers carried more weight than did the votes of the numerically greater younger soldiers. According to Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, the Consul of 63 BC, this design was intentional so that the decisions of the assembly were more in line with the will of the more experienced soldiers who arguably had more to lose. The 170 Centuries of enlisted soldiers were divided into five classes, each with a separate property requirement: The first class consisted of soldiers with heavy armor, the lower classes had successively less armor, and the soldiers of the fifth class had nothing more than slings and stones. Each of the five property classes were divided equally between Centuries of younger soldiers and Centuries of older soldiers. The first class of enlisted soldiers consisted of eighty Centuries, classes two through four consisted of twenty Centuries each, and class five consisted of thirty Centuries. The unarmed soldiers were divided into the final five Centuries: four of these Centuries were composed of artisans and musicians (such as trumpeters and horn blowers), while the fifth Century (the proletarii) consisted of people with little or no property.

Reorganization of the Century Assembly (241 BC- 27 AD)

Under the Servian Organization, the assembly was so aristocratic that the officer class and the first class of enlisted soldiers controlled enough Centuries for an outright majority. In 241 BC, this assembly was reorganized by the Censors Marcus Fabius ButeoMarcus Fabius Buteo

Marcus Fabius Buteo was a Roman politician during the 3rd century BC. He served as consul and as censor, and in 216 BC, being the oldest living ex-censor, he was appointed dictator, legendo senatui, for the purpose of filling vacancies in the senate after the Battle of Cannae. He was appointed by...

and Gaius Aurelius Cotta, in order to give more weight to the lower ranking Centuries, and thus make the assembly less aristocratic. Under the old system, there were a total of 193 Centuries, while under the new system, there were a total of 373 Centuries. Under the new system, the thirty-five Tribes were each divided into ten Centuries: five of older soldiers, and five of younger soldiers. Of each of these five Centuries, one was assigned to one of the five property classes. Therefore, each Tribe had two Centuries (one of older soldiers and one of younger soldiers) allocated to each of the five property classes. In addition, the property requirements for each of the five classes were probably raised. In total, this resulted in 350 Centuries of enlisted soldiers. The same eighteen Centuries of officers, and the same five Centuries of unarmed soldiers, were also included in the redesign. Now, majorities usually could not be reached until the third class of enlisted Centuries had begun voting.

Since the lowest ranking Century in the Century Assembly, the fifth unarmed Century (the proletarii), was always the last Century to vote, it never had any real influence on elections, and as such, it was so poorly regarded that it was all but ignored during the Census. In 107 BC, in response to high unemployment and a severe manpower shortage in the army, the general and Consul Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius was a Roman general and statesman. He was elected consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his dramatic reforms of Roman armies, authorizing recruitment of landless citizens, eliminating the manipular military formations, and reorganizing the...

reformed the organization of the army

Marian reforms

The Marian reforms of 107 BC were a group of military reforms initiated by Gaius Marius, a statesman and general of the Roman republic.- Roman army before the Marian reforms :...

, and allowed individuals with no property to enlist. As a consequence of these reforms, this fifth unarmed Century came to encompass almost the entire Roman army. This mass disenfranchisement of most of the soldiers in the army played an important role in the chaos that led to the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC.

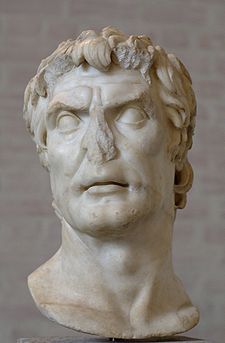

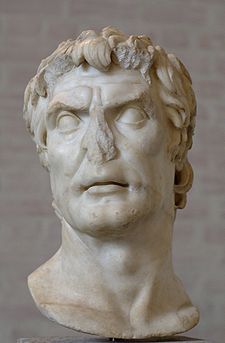

During his dictatorship

Roman dictator

In the Roman Republic, the dictator , was an extraordinary magistrate with the absolute authority to perform tasks beyond the authority of the ordinary magistrate . The office of dictator was a legal innovation originally named Magister Populi , i.e...

from 82 BC until 80 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

restored the old Servian organization to this assembly. This reform was one in a slate of constitutional reforms enacted by Sulla as a consequence of the recent Civil War between his supporters and those of the politically-populist then-former Consul Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius was a Roman general and statesman. He was elected consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his dramatic reforms of Roman armies, authorizing recruitment of landless citizens, eliminating the manipular military formations, and reorganizing the...

. His reforms were intended to reassert aristocratic control over the constitution, and thus prevent the emergence of another Marius. Sulla died in 78 BC, and in 70 BC, the Consuls Pompey Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

and Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and politician who commanded the right wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the...

repealed Sulla's constitutional reforms, including his restoration of the Servian Organization to this assembly. They restored the less aristocratic organization (from 241 BC by the Censors Marcus Fabius Buteo

Marcus Fabius Buteo

Marcus Fabius Buteo was a Roman politician during the 3rd century BC. He served as consul and as censor, and in 216 BC, being the oldest living ex-censor, he was appointed dictator, legendo senatui, for the purpose of filling vacancies in the senate after the Battle of Cannae. He was appointed by...

and Gaius Aurelius Cotta). The organization of the Century Assembly was not changed again until its powers were all transferred to the Roman Senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

by the first Roman Emperor

Roman Emperor

The Roman emperor was the ruler of the Roman State during the imperial period . The Romans had no single term for the office although at any given time, a given title was associated with the emperor...

, Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

, after the fall of the Roman Republic in 27

See also

Primary sources

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius