Anekantavada

Encyclopedia

is one of the most important and fundamental doctrines of Jainism

. It refers to the principles of pluralism

and multiplicity of viewpoints, the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth.

Jains contrast all attempts to proclaim absolute truth with adhgajanyāyah, which can be illustrated through the parable of the "blind men and an elephant

". In this story, each blind man felt a different part of an elephant (trunk, leg, ear, etc.). All the men claimed to understand and explain the true appearance of the elephant, but could only partly succeed, due to their limited perspectives. This principle is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. According to the Jains, only the Kevalins

—omniscient beings—can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge. Consequently, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth

.

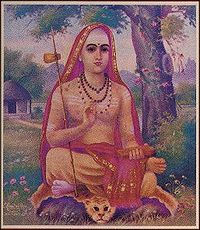

The origins of anekāntavāda can be traced back to the teachings of Mahāvīra

(599–527 BCE), the 24th Jain . The dialectic

al concepts of syādvāda "conditioned viewpoints" and nayavāda "partial viewpoints" arose from anekāntavāda, providing it with more detailed logical structure and expression. The Sanskrit

compound literally means "doctrine of non-exclusivity or multiple viewpoints (an- "not", eka- "one", vada- "viewpoint")"; it is roughly translated into English as "non-absolutism

". An

-ekānta "uncertainty, non-exclusivity" is the opposite of (+) "exclusiveness, absoluteness, necessity" (or also "monotheistic doctrine").

Anekāntavāda encourages its adherents to consider the views and beliefs of their rivals and opposing parties. Proponents of anekāntavāda apply this principle to religion

and philosophy

, reminding themselves that any religion or philosophy—even Jainism—which clings too dogmatically to its own tenets, is committing an error based on its limited point of view. The principle of anekāntavāda also influenced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to adopt principles of religious tolerance, and satyagraha

.

words: anekānta ("manifoldness") and vāda ("school of thought"). The word anekānta is a compound of the Sanskrit negative prefix an, eka ("one"), and anta ("attribute"). Hence, anekānta means "not of solitary attribute". The Jain doctrine lays a strong emphasis on samyaktva, that is, rationality and logic. According to Jains, the ultimate principle should always be logical and no principle can be devoid of logic or reason. Thus, the Jain texts contain deliberative exhortations on every subject, whether they are constructive or obstructive, inferential or analytical, enlightening or destructive.

used for logic and reasoning. The other two are:

These Jain philosophical

concepts made important contributions to ancient Indian philosophy

, especially in the areas of skepticism and relativity.

is the theory of conditioned

predication

, which provides an expression to anekānta by recommending that the epithet Syād be prefixed to every phrase or expression. Syādvāda is not only an extension of anekānta ontology

, but a separate system of logic capable of standing on its own. The Sanskrit etymological root of the term syād is "perhaps" or "maybe", but in the context of syādvāda, it means "in some ways" or "from a perspective". As reality is complex, no single proposition can express the nature of reality fully. Thus the term "syāt" should be prefixed before each proposition giving it a conditional point of view and thus removing any dogmatism in the statement. Since it ensures that each statement is expressed from seven different conditional and relative viewpoints or propositions, syādvāda is known as saptibhaṅgīnāya or the theory of seven conditioned predications. These seven propositions, also known as saptibhaṅgī, are:

Each of these seven propositions examines the complex and multifaceted nature of reality from a relative point of view of time, space, substance and mode. To ignore the complexity of reality is to commit the fallacy of dogmatism.

words—naya ("partial viewpoint") and vāda ("school of thought or debate"). It is used to arrive at a certain inference

from a point of view. An object has infinite aspects to it, but when we describe an object in practice, we speak of only relevant aspects and ignore irrelevant ones. This does not deny the other attributes, qualities, modes and other aspects; they are just irrelevant from a particular perspective. Authors like Natubhai Shah explain nayavāda with the example of a car; for instance, when we talk of a "blue BMW

" we are simply considering the color and make of the car. However, our statement does not imply that the car is devoid of other attributes like engine type, cylinders, speed, price and the like. This particular viewpoint is called a naya or a partial viewpoint. As a type of critical philosophy

, nayavāda holds that all philosophical disputes arise out of confusion of standpoints, and the standpoints we adopt are, although we may not realize it, "the outcome of purposes that we may pursue". While operating within the limits of language and seeing the complex nature of reality, Māhavīra

used the language of nayas. Naya, being a partial expression of truth, enables us to comprehend reality part by part.

The age of Māhavīra and Buddha

The age of Māhavīra and Buddha

was an age of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self. Upanishadic thought postulated the absolute unchanging reality of Brahman

and Ātman

and claimed that change was mere illusion. The theory advanced by Buddhists denied the reality of permanence of conditioned phenomena

, asserting only interdependence and impermanence. According to the vedāntin (Upanishadic) conceptual scheme, the Buddhists were wrong in denying permanence and absolutism, and within the Buddhist conceptual scheme, the vedāntins were wrong in denying the reality of impermanence. The two positions were contradictory and mutually exclusive from each others' point of view. The Jains managed a synthesis of the two uncompromising positions with anekāntavāda. From the perspective of a higher, inclusive level made possible by the ontology

and epistemology of anekāntavāda and syādvāda, Jains do not see such claims as contradictory or mutually exclusive; instead, they are seen as ekantika or only partially true. The Jain breadth of vision embraces the perspectives of both Vedānta which, according to Jainism, "recognizes substances but not process", and Buddhism, which "recognizes process but not substance". Jainism, on the other hand, pays equal attention to both substance (dravya) and process (paryaya).

Mahāvīra's responses to various questions asked by his disciples and recorded in the Jain canon Vyakhyaprajnapti

demonstrate recognition that there are complex and multiple aspects to truth and reality and a mutually exclusive approach cannot be taken to explain such reality:

Thousands of questions were asked and Mahāvīra’s responses suggested a complex and multifaceted reality with each answer qualified from a viewpoint. According to Jainism, even a , who possesses and perceives infinite knowledge, cannot express reality completely because of the limitations of language, which is of human creation.

This philosophical syncretisation of paradox of change through anekānta has been acknowledged by modern scholars such as Arvind Sharma

, who wrote:

However, anekāntavāda is simply not about syncretisation or compromise between competing ideas, as it is about finding the hidden elements of shared truth between such ideas. Anekāntavāda is not about denying the truth; rather truth is acknowledged as an ultimate spiritual goal. For ordinary humans, it is an elusive goal, but they are still obliged to work towards its attainment. Anekāntavāda also does not mean compromising or diluting ones own values and principles. On the contrary, it allows us to understand and be tolerant of conflicting and opposing views, while respectfully maintaining the validity of ones own view-point. Hence, John Koller calls anekāntavāda as – “epistemological respect for view of others”. Anekāntavāda, thus, did not prevent the Jain thinkers from defending the truth and validity of their own doctrine while simultaneously respecting and understanding the rival doctrines. Anne Vallely notes that the epistemological respect for other viewpoints was put to practice when she was invited by Ācārya Tulsi

, the head of the Terāpanthī order, to teach sadhvi

s the tenets of Christianity

. Commenting on their adherence to and anekāntavāda, she says:

Anekāntavāda is also different from moral relativism

. It does not mean conceding that all arguments and all views are equal, but rather logic and evidence determine which views are true, in what respect and to what extent. While employing anekāntavāda, the 17th century philosopher monk, also cautions against anābhigrahika (indiscriminate attachment to all views as being true), which is effectively a kind of misconceived relativism. Jains thus consider anekāntavāda as a positive concept corresponding to religious pluralism

that transcends monism

and dualism

, implying a sophisticated conception of a complex reality. It does not merely involve rejection of partisanship, but reflects a positive spirit of reconciliation of opposite views. However, it is argued that pluralism often degenerates to some form of moral relativism

or religious exclusivism

. According to Anne Vallely, anekānta is a way out of this epistemological quagmire, as it makes a genuinely pluralistic view possible without lapsing into extreme moral relativism or exclusivity.

The ancient Jain texts often explain the concepts of anekāntvāda and syādvāda with the parable

The ancient Jain texts often explain the concepts of anekāntvāda and syādvāda with the parable

of the blind men and an elephant

(Andhgajanyāyah), which addresses the manifold nature of truth.

Two of the many references to this parable are found in Tattvarthaslokavatika of Vidyanandi (9th century) and Syādvādamanjari of Ācārya Mallisena (13th century). Mallisena uses the parable to argue that immature people deny various aspects of truth; deluded by the aspects they do understand, they deny the aspects they don't understand. "Due to extreme delusion produced on account of a partial viewpoint, the immature deny one aspect and try to establish another. This is the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant." Mallisena also cites the parable when noting the importance of considering all viewpoints in obtaining a full picture of reality. "It is impossible to properly understand an entity consisting of infinite properties without the method of modal description consisting of all viewpoints, since it will otherwise lead to a situation of seizing mere sprouts (i.e., a superficial, inadequate cognition), on the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant."

concepts. The development of anekāntavāda also encouraged the development of the dialectics of syādvāda

(conditioned viewpoints), saptibhaṅgī (the seven conditioned predication), and nayavāda (partial viewpoints).

that contained teachings of the prior to Māhavīra. German Indologist

Hermann Jacobi

believes Māhavīra effectively employed the dialectics of anekāntavāda to refute the agnosticism

of . Sutrakritanga

, the second oldest canon of Jainism, contains the first references to syādvāda and . According to Sūtrakritanga, Māhavīra advised his disciples to use syādvāda to preach his teachings:

contains references to Vibhagyavāda, which, according to Jacobi, is the same as syādvāda and saptibhaṅgī. The early Jain canons and teachings contained multitudes of references to anekāntavāda and syādvāda in rudimentary form without giving it proper structure or establishing it as a separate doctrine. Bhagvatisūtra mentions only three primary predications of the saptibhaṅgīnaya. After Māhavīra, Kundakunda

(1st century CE) was the first author–saint to expound on the doctrine of syādvāda and saptibhaṅgī and give it a proper structure in his famous works Pravacanasāra and Pancastikayasāra

. Kundakunda also used nayas to discuss the essence of the self

in Samayasāra

. Proper classification of the nayas was provided by the philosopher monk, Umāsvāti (2nd century CE) in Tattvārthasūtra

. Samantabhadra (2nd century CE) and Siddhasena Divākara (3rd century CE) further fine-tuned Jain epistemology and logic by expounding on the concepts of anekāntavāda in proper form and structure.

Ācārya Siddhasena Divākara

expounded on the nature of truth in the court of King Vikramāditya

:

In Sanmatitarka, Divākara further adds: "All doctrines are right in their own respective spheres—but if they encroach upon the province of other doctrines and try to refute their view, they are wrong. A man who holds the view of the cumulative character of truth never says that a particular view is right or that a particular view is wrong."

. By the time of Akalanka (5th century CE), whose works are a landmark in Jain logic, anekāntavāda was firmly entrenched in Jain texts, as is evident from the various teachings of the Jain scriptures.

Ācārya Haribhadra

(8th century CE) was one of the leading proponents of anekāntavāda. He was the first classical author to write a doxography

, a compendium of a variety of intellectual views. This attempted to contextualise Jain thoughts within the broad framework, rather than espouse narrow partisan views. It interacted with the many possible intellectual orientations available to Indian thinkers around the 8th century.

Ācārya Amrtacandra starts his famous 10th century CE work Purusathasiddhiupaya with strong praise for anekāntavāda: "I bow down to the principle of anekānta, the source and foundation of the highest scriptures, the dispeller of wrong one-sided notions, that which takes into account all aspects of truth, reconciling diverse and even contradictory traits of all objects or entity."

Ācārya Vidyānandi (11th century CE) provides the analogy of the ocean to explain the nature of truth in Tattvarthaslokavārtikka, 116: "Water from the ocean contained in a pot can neither be called an ocean nor a non-ocean, but simply a part of ocean. Similarly, a doctrine, though arising from absolute truth can neither be called a whole truth nor a non-truth."

, a 17th century Jain monk, went beyond anekāntavāda by advocating madhāyastha, meaning "standing in the middle" or "equidistance". This position allowed him to praise qualities in others even though the people were non-Jain and belonged to other faiths. There was a period of stagnation after Yasovijayaji, as there were no new contributions to the development of Jain philosophy.

s, and Christian

s at various times. According to Hermann Jacobi

, Māhavīra

used such concepts as syādvāda and saptbhangi to silence some of his opponents. The discussions of the agnostics led by had probably influenced many of their contemporaries and consequently syādvāda may have seemed to them a way out of ajñānavāda. Jacobi further speculates that many of their followers would have gone over to Māhavīra's creed, convinced of the truth of the saptbhanginaya. According to Professor Christopher Key Chapple, anekāntavāda allowed Jains to survive during the most hostile and unfavourable moments in history. According to John Koller, professor of Asian studies

, anekāntavāda allowed Jain thinkers to maintain the validity of their doctrine, while at the same time respectfully criticizing the views of their opponents.

Anekāntavāda was often used by Jain monks to obtain royal patronage from Hindu Kings. Ācārya Hemacandra

used anekāntavāda to gain the confidence and respect of the Cālukya

Emperor Jayasimha Siddharaja. According to the Jain text Prabandhacantamani, Emperor Siddharaja desired enlightenment and liberation and he questioned teachers from various traditions. He remained in a quandary when he discovered that they all promoted their own teachings while disparaging other teachings. Among the teachers he questioned was Hemacandra, who, rather than promote Jainism, told him a story with a different message. According to his story, a sick man was cured of his disease after eating all the herbs available, as he was not aware which herb was medicinal. The moral of the tale, according to Hemacandra, was that just as the man was restored by the herb, even though no one knew which particular herb did the trick, so in the kaliyuga

("age of vice") the wise should obtain salvation by supporting all religious traditions, even though no-one can say with absolute certainty which tradition it is that provides that salvation.

is the only correct religious path. It is thus an intellectual , or of the mind. Burch writes, "Jain logic is intellectual . Just as a right-acting person respects the life of all beings, so a right-thinking person acknowledges the validity of all judgments. This means recognizing all aspects of reality, not merely one or some aspects, as is done in non-Jain philosophies."

Māhavīra encouraged his followers to study and understand rival traditions in his Acaranga Sutra

: "Comprehend one philosophical view through the comprehensive study of another one."

In anekāntavāda, there is no "battle of ideas", because this is considered to be a form of intellectual himsa or violence, leading quite logically to physical violence and war. In today's world, the limitations of the adversarial, "either with us or against us

" form of argument are increasingly apparent by the fact that the argument leads to political, religious and social conflicts. Sūtrakrtānga

, the second oldest canon of Jainism, provides a solution by stating: "Those who praise their own doctrines and ideology and disparage the doctrine of others distort the truth and will be confined to the cycle of birth and death."

This ecumenical and irenical attitude, engendered by anekāntavāda, allowed modern Jain monks such as Vijayadharmasuri to declare: "I am neither a Jain nor a Buddhist, a Vaisnava nor a Saivite, a Hindu

nor a Muslim

, but a traveler on the path of peace shown by the supreme soul, the God who is free from passion."

in general and anekāntavāda in particular can provide a solution to many problems facing the world. They claim that even the mounting ecological crisis is linked to adversarialism, because it arises from a false division between humanity and "the rest" of nature. Modern judicial systems, democracy, freedom of speech

, and secularism

all implicitly reflect an attitude of anekāntavāda. Many authors, such as Kamla Jain, have claimed that the Jain tradition, with its emphasis on ahimsā and anekāntavāda, is capable of solving religious intolerance, terrorism

, wars, the depletion of natural resources, environmental degradation and many other problems. Referring to the September 11 attacks, John Koller believes that violence in society mainly exists due to faulty epistemology and metaphysics as well as faulty ethics. A failure to respect the life and views of others, rooted in dogmatic and mistaken knowledge and refusal to acknowledge the legitimate claims of different perspectives, leads to violent and destructive behavior. Koller suggests that anekāntavāda has a larger role to play in the world peace. According to Koller, because anekāntavāda is designed to avoid one-sided errors, reconcile contradictory viewpoints, and accept the multiplicity and relativity of truth, the Jain philosophy is in a unique position to support dialogue and negotiations amongst various nations and peoples.

Some Indologists like Professor John Cort have cautioned against giving undue importance to "intellectual " as the basis of anekāntavāda. He points out that Jain monks have also used anekāntavāda and syādvāda as debating weapons to silence their critics and prove the validity of the Jain doctrine over others. According to Dundas, in Jain hands, this method of analysis became a fearsome weapon of philosophical polemic

with which the doctrines of Hinduism

and Buddhism

could be pared down to their ideological bases of simple permanence and impermanence, respectively, and thus could be shown to be one-pointed and inadequate as the overall interpretations of reality they purported to be.Dundas, Paul (2002) p. 192 On the other hand, the many-sided approach was claimed by the Jains to be immune from criticism since it did not present itself as a philosophical or dogmatic view.

, and Stephen Hay, these early childhood impressions and experiences contributed to the formation of Gandhi's character and his further moral and spiritual development. In his writings, Mahatma Gandhi attributed his seemingly contradictory positions over a period of time to the learning process, experiments with truth and his belief in anekāntavāda. He proclaimed that the duty of every individual is to determine what is personally true and act on that relative perception of truth. According to Gandhi, a satyagrahi

is duty bound to act according to his relative truth, but at the same time, he is also equally bound to learn from truth held by his opponent. In response to a friend's query on religious tolerance, he responded in the journal "Young India

- 21 Jan 1926":

In defense of the doctrine, Jains point out that anekāntavāda seeks to reconcile apparently opposing viewpoints rather than refuting them.

Anekāntavāda received much criticism from the Vedantists, notably Adi Sankarācārya

Anekāntavāda received much criticism from the Vedantists, notably Adi Sankarācārya

(9th century C.E.). Sankara argued against some tenets of Jainism in his bhasya on Brahmasutra (2:2:33–36). His main arguments centre on anekāntavāda:

However, many believe that Sankara fails to address genuine anekāntavāda. By identifying syādavāda with sansayavāda, he instead addresses "agnosticism

", which was argued by . Many authors like Pandya believe that Sankara overlooked that, the affirmation of the existence of an object is in respect to the object itself, and its negation is in respect to what the object is not. Genuine anekāntavāda thus considers positive and negative attributes of an object, at the same time, and without any contradictions.

Another Buddhist logician Dharmakirti

ridiculed anekāntavāda in Pramānavarttikakārika: "With the differentiation removed, all things have dual nature. Then, if somebody is implored to eat curd, then why he does not eat camel?" The insinuation is obvious; if curd exists from the nature of curd and does not exist from the nature of a camel, then one is justified in eating camel, as by eating camel, he is merely eating the negation of curd. Ācārya Akalanka, while agreeing that Dharmakirti may be right from one viewpoint, took it upon himself to issue a rejoinder:

Jainism

Jainism is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state...

. It refers to the principles of pluralism

Pluralism (philosophy)

Pluralism is a term used in philosophy, meaning "doctrine of multiplicity", often used in opposition to monism and dualism . The term has different connotations in metaphysics and epistemology...

and multiplicity of viewpoints, the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth.

Jains contrast all attempts to proclaim absolute truth with adhgajanyāyah, which can be illustrated through the parable of the "blind men and an elephant

Blind Men and an Elephant

The story of the blind men and an elephant originated in India from where it is widely diffused. It has been used to illustrate a range of truths and fallacies...

". In this story, each blind man felt a different part of an elephant (trunk, leg, ear, etc.). All the men claimed to understand and explain the true appearance of the elephant, but could only partly succeed, due to their limited perspectives. This principle is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. According to the Jains, only the Kevalins

Kevala Jnana

In Jainism, ' or ' , "Perfect or Absolute Knowledge", is the highest form of knowledge that a soul can attain. A person who has attained is called a Kevalin, which is synonymous with Jina "victor" and Arihant "the worthy one"...

—omniscient beings—can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge. Consequently, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth

Universality (philosophy)

In philosophy, universalism is a doctrine or school claiming universal facts can be discovered and is therefore understood as being in opposition to relativism. In certain religions, universality is the quality ascribed to an entity whose existence is consistent throughout the universe...

.

The origins of anekāntavāda can be traced back to the teachings of Mahāvīra

Mahavira

Mahāvīra is the name most commonly used to refer to the Indian sage Vardhamāna who established what are today considered to be the central tenets of Jainism. According to Jain tradition, he was the 24th and the last Tirthankara. In Tamil, he is referred to as Arukaṉ or Arukadevan...

(599–527 BCE), the 24th Jain . The dialectic

Dialectic

Dialectic is a method of argument for resolving disagreement that has been central to Indic and European philosophy since antiquity. The word dialectic originated in Ancient Greece, and was made popular by Plato in the Socratic dialogues...

al concepts of syādvāda "conditioned viewpoints" and nayavāda "partial viewpoints" arose from anekāntavāda, providing it with more detailed logical structure and expression. The Sanskrit

Sanskrit

Sanskrit , is a historical Indo-Aryan language and the primary liturgical language of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.Buddhism: besides Pali, see Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Today, it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand...

compound literally means "doctrine of non-exclusivity or multiple viewpoints (an- "not", eka- "one", vada- "viewpoint")"; it is roughly translated into English as "non-absolutism

Problem of universals

The problem of universals is an ancient problem in metaphysics about whether universals exist. Universals are general or abstract qualities, characteristics, properties, kinds or relations, such as being male/female, solid/liquid/gas or a certain colour, that can be predicated of individuals or...

". An

Privative a

In Ancient Greek grammar, privative a is the prefix a- that expresses negation or absence . It is derived from a Proto-Indo-European syllabic nasal *, the zero ablaut grade of the negation *ne, i.e. /n/ used as a vowel...

-ekānta "uncertainty, non-exclusivity" is the opposite of (+) "exclusiveness, absoluteness, necessity" (or also "monotheistic doctrine").

Anekāntavāda encourages its adherents to consider the views and beliefs of their rivals and opposing parties. Proponents of anekāntavāda apply this principle to religion

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

and philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, reminding themselves that any religion or philosophy—even Jainism—which clings too dogmatically to its own tenets, is committing an error based on its limited point of view. The principle of anekāntavāda also influenced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to adopt principles of religious tolerance, and satyagraha

Satyagraha

Satyagraha , loosely translated as "insistence on truth satya agraha soul force" or "truth force" is a particular philosophy and practice within the broader overall category generally known as nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. The term "satyagraha" was conceived and developed by Mahatma...

.

Philosophical overview

The etymological root of anekāntavāda lies in the compound of two SanskritSanskrit

Sanskrit , is a historical Indo-Aryan language and the primary liturgical language of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.Buddhism: besides Pali, see Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Today, it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand...

words: anekānta ("manifoldness") and vāda ("school of thought"). The word anekānta is a compound of the Sanskrit negative prefix an, eka ("one"), and anta ("attribute"). Hence, anekānta means "not of solitary attribute". The Jain doctrine lays a strong emphasis on samyaktva, that is, rationality and logic. According to Jains, the ultimate principle should always be logical and no principle can be devoid of logic or reason. Thus, the Jain texts contain deliberative exhortations on every subject, whether they are constructive or obstructive, inferential or analytical, enlightening or destructive.

Jain doctrines of relativity

Anekāntavāda is one of the three Jain doctrines of relativityRelativism

Relativism is the concept that points of view have no absolute truth or validity, having only relative, subjective value according to differences in perception and consideration....

used for logic and reasoning. The other two are:

- syādvāda—the theory of conditioned predication and;

- nayavāda—the theory of partial standpoints.

These Jain philosophical

Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy deals extensively with the problems of metaphysics, reality, cosmology, ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is essentially a transtheistic religion of ancient India. It is a continuation of the ancient tradition which co-existed with the Vedic tradition since ancient...

concepts made important contributions to ancient Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy

India has a rich and diverse philosophical tradition dating back to ancient times. According to Radhakrishnan, the earlier Upanisads constitute "...the earliest philosophical compositions of the world."...

, especially in the areas of skepticism and relativity.

Syādvāda

SyādvādaSyadvada

Syādvāda is the Doctrine of Postulation of Jainism. In other words, Syādvāda provides the body of teachings or instruction which one uses to derive a postulate or axiom. The starting assumption or postulate is given as saptabhanginaya, from which other statements are logically derived...

is the theory of conditioned

Conditional sentence

In grammar, conditional sentences are sentences discussing factual implications or hypothetical situations and their consequences. Languages use a variety of conditional constructions and verb forms to form such sentences....

predication

Predicate (grammar)

There are two competing notions of the predicate in theories of grammar. Traditional grammar tends to view a predicate as one of two main parts of a sentence, the other being the subject, which the predicate modifies. The other understanding of predicates is inspired from work in predicate calculus...

, which provides an expression to anekānta by recommending that the epithet Syād be prefixed to every phrase or expression. Syādvāda is not only an extension of anekānta ontology

Ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of the nature of being, existence or reality as such, as well as the basic categories of being and their relations...

, but a separate system of logic capable of standing on its own. The Sanskrit etymological root of the term syād is "perhaps" or "maybe", but in the context of syādvāda, it means "in some ways" or "from a perspective". As reality is complex, no single proposition can express the nature of reality fully. Thus the term "syāt" should be prefixed before each proposition giving it a conditional point of view and thus removing any dogmatism in the statement. Since it ensures that each statement is expressed from seven different conditional and relative viewpoints or propositions, syādvāda is known as saptibhaṅgīnāya or the theory of seven conditioned predications. These seven propositions, also known as saptibhaṅgī, are:

- syād-asti—in some ways, it is,

- syād-nāsti—in some ways, it is not,

- syād-asti-nāsti—in some ways, it is, and it is not,

- —in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable,

- —in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable,

- —in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable,

- —in some ways, it is indescribable.

Each of these seven propositions examines the complex and multifaceted nature of reality from a relative point of view of time, space, substance and mode. To ignore the complexity of reality is to commit the fallacy of dogmatism.

Nayavāda

Nayavāda is the theory of partial standpoints or viewpoints. Nayavāda is a compound of two SanskritSanskrit

Sanskrit , is a historical Indo-Aryan language and the primary liturgical language of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.Buddhism: besides Pali, see Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Today, it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand...

words—naya ("partial viewpoint") and vāda ("school of thought or debate"). It is used to arrive at a certain inference

Inference

Inference is the act or process of deriving logical conclusions from premises known or assumed to be true. The conclusion drawn is also called an idiomatic. The laws of valid inference are studied in the field of logic.Human inference Inference is the act or process of deriving logical conclusions...

from a point of view. An object has infinite aspects to it, but when we describe an object in practice, we speak of only relevant aspects and ignore irrelevant ones. This does not deny the other attributes, qualities, modes and other aspects; they are just irrelevant from a particular perspective. Authors like Natubhai Shah explain nayavāda with the example of a car; for instance, when we talk of a "blue BMW

BMW

Bayerische Motoren Werke AG is a German automobile, motorcycle and engine manufacturing company founded in 1916. It also owns and produces the Mini marque, and is the parent company of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars. BMW produces motorcycles under BMW Motorrad and Husqvarna brands...

" we are simply considering the color and make of the car. However, our statement does not imply that the car is devoid of other attributes like engine type, cylinders, speed, price and the like. This particular viewpoint is called a naya or a partial viewpoint. As a type of critical philosophy

Critical philosophy

Attributed to Immanuel Kant, the critical philosophy movement sees the primary task of philosophy as criticism rather than justification of knowledge; criticism, for Kant, meant judging as to the possibilities of knowledge before advancing to knowledge itself...

, nayavāda holds that all philosophical disputes arise out of confusion of standpoints, and the standpoints we adopt are, although we may not realize it, "the outcome of purposes that we may pursue". While operating within the limits of language and seeing the complex nature of reality, Māhavīra

Mahavira

Mahāvīra is the name most commonly used to refer to the Indian sage Vardhamāna who established what are today considered to be the central tenets of Jainism. According to Jain tradition, he was the 24th and the last Tirthankara. In Tamil, he is referred to as Arukaṉ or Arukadevan...

used the language of nayas. Naya, being a partial expression of truth, enables us to comprehend reality part by part.

Syncretisation of changing and unchanging reality

Gautama Buddha

Siddhārtha Gautama was a spiritual teacher from the Indian subcontinent, on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. In most Buddhist traditions, he is regarded as the Supreme Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit: सिद्धार्थ गौतम; Pali: Siddhattha Gotama) was a spiritual teacher from the Indian...

was an age of intense intellectual debates, especially on the nature of reality and self. Upanishadic thought postulated the absolute unchanging reality of Brahman

Brahman

In Hinduism, Brahman is the one supreme, universal Spirit that is the origin and support of the phenomenal universe. Brahman is sometimes referred to as the Absolute or Godhead which is the Divine Ground of all being...

and Ātman

Ātman (Hinduism)

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that means 'self'. In Hindu philosophy, especially in the Vedanta school of Hinduism it refers to one's true self beyond identification with phenomena...

and claimed that change was mere illusion. The theory advanced by Buddhists denied the reality of permanence of conditioned phenomena

Sankhara

' or ' is a term figuring prominently in the teaching of the Buddha. The word means "that which has been put together" and "that which puts together". In the first sense, refers to conditioned phenomena generally but specifically to all mental "dispositions"...

, asserting only interdependence and impermanence. According to the vedāntin (Upanishadic) conceptual scheme, the Buddhists were wrong in denying permanence and absolutism, and within the Buddhist conceptual scheme, the vedāntins were wrong in denying the reality of impermanence. The two positions were contradictory and mutually exclusive from each others' point of view. The Jains managed a synthesis of the two uncompromising positions with anekāntavāda. From the perspective of a higher, inclusive level made possible by the ontology

Ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of the nature of being, existence or reality as such, as well as the basic categories of being and their relations...

and epistemology of anekāntavāda and syādvāda, Jains do not see such claims as contradictory or mutually exclusive; instead, they are seen as ekantika or only partially true. The Jain breadth of vision embraces the perspectives of both Vedānta which, according to Jainism, "recognizes substances but not process", and Buddhism, which "recognizes process but not substance". Jainism, on the other hand, pays equal attention to both substance (dravya) and process (paryaya).

Mahāvīra's responses to various questions asked by his disciples and recorded in the Jain canon Vyakhyaprajnapti

Vyakhyaprajnapti

Vyākhyāprajñapti commonly known as Bhagavati sūtra is the fifth of the 12 Jain āagam said to be promulgated by Bhagwan Mahavara. Vyākhyāprajñapti translated as "Exposition of Explanations" is said to have been composed by Sudharma Swami Gandhara as per the Svethambara tradition. It is the largest...

demonstrate recognition that there are complex and multiple aspects to truth and reality and a mutually exclusive approach cannot be taken to explain such reality:

Thousands of questions were asked and Mahāvīra’s responses suggested a complex and multifaceted reality with each answer qualified from a viewpoint. According to Jainism, even a , who possesses and perceives infinite knowledge, cannot express reality completely because of the limitations of language, which is of human creation.

This philosophical syncretisation of paradox of change through anekānta has been acknowledged by modern scholars such as Arvind Sharma

Arvind Sharma

Arvind Sharma is the Birks Professor of Comparative Religion at McGill University. Sharma's works focus on comparative religion, Hinduism, and the role of women in religion. Some of his more famous works include Our Religions and Women in World Religions...

, who wrote:

However, anekāntavāda is simply not about syncretisation or compromise between competing ideas, as it is about finding the hidden elements of shared truth between such ideas. Anekāntavāda is not about denying the truth; rather truth is acknowledged as an ultimate spiritual goal. For ordinary humans, it is an elusive goal, but they are still obliged to work towards its attainment. Anekāntavāda also does not mean compromising or diluting ones own values and principles. On the contrary, it allows us to understand and be tolerant of conflicting and opposing views, while respectfully maintaining the validity of ones own view-point. Hence, John Koller calls anekāntavāda as – “epistemological respect for view of others”. Anekāntavāda, thus, did not prevent the Jain thinkers from defending the truth and validity of their own doctrine while simultaneously respecting and understanding the rival doctrines. Anne Vallely notes that the epistemological respect for other viewpoints was put to practice when she was invited by Ācārya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi was a Jainist Acharya . He was the founder of the Anuvrata and the Jain Vishva Bharti Institute, Ladnun and the author of over one-hundred books. Dr. Radhakrishnan in his "Living with Purpose" included him in the world's 15 great persons. He was given the title "Yuga-Pradhan" in a...

, the head of the Terāpanthī order, to teach sadhvi

Sadhu

In Hinduism, sādhu denotes an ascetic, wandering monk. Although the vast majority of sādhus are yogīs, not all yogīs are sādhus. The sādhu is solely dedicated to achieving mokṣa , the fourth and final aśrama , through meditation and contemplation of brahman...

s the tenets of Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

. Commenting on their adherence to and anekāntavāda, she says:

Anekāntavāda is also different from moral relativism

Moral relativism

Moral relativism may be any of several descriptive, meta-ethical, or normative positions. Each of them is concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different people and cultures:...

. It does not mean conceding that all arguments and all views are equal, but rather logic and evidence determine which views are true, in what respect and to what extent. While employing anekāntavāda, the 17th century philosopher monk, also cautions against anābhigrahika (indiscriminate attachment to all views as being true), which is effectively a kind of misconceived relativism. Jains thus consider anekāntavāda as a positive concept corresponding to religious pluralism

Religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is a loosely defined expression concerning acceptance of various religions, and is used in a number of related ways:* As the name of the worldview according to which one's religion is not the sole and exclusive source of truth, and thus that at least some truths and true values...

that transcends monism

Monism

Monism is any philosophical view which holds that there is unity in a given field of inquiry. Accordingly, some philosophers may hold that the universe is one rather than dualistic or pluralistic...

and dualism

Dualism

Dualism denotes a state of two parts. The term 'dualism' was originally coined to denote co-eternal binary opposition, a meaning that is preserved in metaphysical and philosophical duality discourse but has been diluted in general or common usages. Dualism can refer to moral dualism, Dualism (from...

, implying a sophisticated conception of a complex reality. It does not merely involve rejection of partisanship, but reflects a positive spirit of reconciliation of opposite views. However, it is argued that pluralism often degenerates to some form of moral relativism

Moral relativism

Moral relativism may be any of several descriptive, meta-ethical, or normative positions. Each of them is concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different people and cultures:...

or religious exclusivism

Religious exclusivism

Religious exclusivism is the doctrine that only one particular religion is true. In its normative form it is simply the belief in one's own religion and non-belief in religions other than one's own...

. According to Anne Vallely, anekānta is a way out of this epistemological quagmire, as it makes a genuinely pluralistic view possible without lapsing into extreme moral relativism or exclusivity.

Parable of the blind men and elephant

Parable

A parable is a succinct story, in prose or verse, which illustrates one or more instructive principles, or lessons, or a normative principle. It differs from a fable in that fables use animals, plants, inanimate objects, and forces of nature as characters, while parables generally feature human...

of the blind men and an elephant

Blind Men and an Elephant

The story of the blind men and an elephant originated in India from where it is widely diffused. It has been used to illustrate a range of truths and fallacies...

(Andhgajanyāyah), which addresses the manifold nature of truth.

Two of the many references to this parable are found in Tattvarthaslokavatika of Vidyanandi (9th century) and Syādvādamanjari of Ācārya Mallisena (13th century). Mallisena uses the parable to argue that immature people deny various aspects of truth; deluded by the aspects they do understand, they deny the aspects they don't understand. "Due to extreme delusion produced on account of a partial viewpoint, the immature deny one aspect and try to establish another. This is the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant." Mallisena also cites the parable when noting the importance of considering all viewpoints in obtaining a full picture of reality. "It is impossible to properly understand an entity consisting of infinite properties without the method of modal description consisting of all viewpoints, since it will otherwise lead to a situation of seizing mere sprouts (i.e., a superficial, inadequate cognition), on the maxim of the blind (men) and the elephant."

History and development

The principle of anekāntavāda is the foundation of many Jain philosophicalJain philosophy

Jain philosophy deals extensively with the problems of metaphysics, reality, cosmology, ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is essentially a transtheistic religion of ancient India. It is a continuation of the ancient tradition which co-existed with the Vedic tradition since ancient...

concepts. The development of anekāntavāda also encouraged the development of the dialectics of syādvāda

Syadvada

Syādvāda is the Doctrine of Postulation of Jainism. In other words, Syādvāda provides the body of teachings or instruction which one uses to derive a postulate or axiom. The starting assumption or postulate is given as saptabhanginaya, from which other statements are logically derived...

(conditioned viewpoints), saptibhaṅgī (the seven conditioned predication), and nayavāda (partial viewpoints).

Origins

The origins of anekāntavāda lie in the teachings of Māhavīra, who used it effectively to show the relativity of truth and reality. Taking a relativistic viewpoint, Māhavīra is said to have explained the nature of the soul as both permanent, from the point of view of underlying substance, and temporary, from the point of view of its modes and modification. The importance and antiquity of anekāntavāda are also demonstrated by the fact that it formed the subject matter of Astinasti Pravāda, the fourth part of the lost PurvaPurvas

The Fourteen Purvas, translated as ancient or prior knowledge, are a large body of Jain scriptures that was preached by all Tirthankaras of Jainism encompassing the entire gamut of knowledge available in this universe. The persons having the knowledge of purvas were given an exalted status of...

that contained teachings of the prior to Māhavīra. German Indologist

Indology

Indology is the academic study of the history and cultures, languages, and literature of the Indian subcontinent , and as such is a subset of Asian studies....

Hermann Jacobi

Hermann Jacobi

Hermann Georg Jacobi was an eminent German Indologist.-Education:Jacobi was born in Köln on 11 February 1850...

believes Māhavīra effectively employed the dialectics of anekāntavāda to refute the agnosticism

Agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view that the truth value of certain claims—especially claims about the existence or non-existence of any deity, but also other religious and metaphysical claims—is unknown or unknowable....

of . Sutrakritanga

Sutrakritanga

Sutrakritanga Sutra is the second agama of the 12 main angās of the Jain canons. According to the Svetambara tradition it was written by Gandhara Sudharmasvami in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit...

, the second oldest canon of Jainism, contains the first references to syādvāda and . According to Sūtrakritanga, Māhavīra advised his disciples to use syādvāda to preach his teachings:

Early history

SutrakritangaSutrakritanga

Sutrakritanga Sutra is the second agama of the 12 main angās of the Jain canons. According to the Svetambara tradition it was written by Gandhara Sudharmasvami in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit...

contains references to Vibhagyavāda, which, according to Jacobi, is the same as syādvāda and saptibhaṅgī. The early Jain canons and teachings contained multitudes of references to anekāntavāda and syādvāda in rudimentary form without giving it proper structure or establishing it as a separate doctrine. Bhagvatisūtra mentions only three primary predications of the saptibhaṅgīnaya. After Māhavīra, Kundakunda

Kundakunda

Kundakunda is a celebrated Jain Acharya, Jain scholar monk, 2nd century CE, composer of spiritual classics such as: Samayasara, Niyamasara, Pancastikayasara, Pravacanasara, Atthapahuda and Barasanuvekkha. He occupies the highest place in the tradition of the Jain acharyas.He belonged to the Mula...

(1st century CE) was the first author–saint to expound on the doctrine of syādvāda and saptibhaṅgī and give it a proper structure in his famous works Pravacanasāra and Pancastikayasāra

Pancastikayasara

Pañcastikayasara, or the essence of reality, is a Digambara text by Kundakunda is part of his trilogy, known as the prahbrta-traya or the nataka-traya. Kundakunda explains the Jaina concepts of Ontology and Ethics...

. Kundakunda also used nayas to discuss the essence of the self

Self (philosophy)

The philosophy of self defines the essential qualities that make one person distinct from all others. There have been numerous approaches to defining these qualities. The self is the idea of a unified being which is the source of consciousness. Moreover, this self is the agent responsible for the...

in Samayasāra

Samayasara

' is a famous Jain text by Acharya Kundakunda.Its ten chapters discuss the nature of jiva , its attachment to karmas and moksha....

. Proper classification of the nayas was provided by the philosopher monk, Umāsvāti (2nd century CE) in Tattvārthasūtra

Tattvartha Sutra

Tattvartha Sutra is a Jain text written by Acharya Umaswati. It was an attempt to bring together the different elements of the Jain path, epistemological, metaphysical, cosmological, ethical and practical, otherwise unorganized around the scriptures in an unsystematic format...

. Samantabhadra (2nd century CE) and Siddhasena Divākara (3rd century CE) further fine-tuned Jain epistemology and logic by expounding on the concepts of anekāntavāda in proper form and structure.

Ācārya Siddhasena Divākara

Siddhasen Diwakar

Siddhasen Diwakar was a highly intelligent Jain acharya of his time. Siddhasen could study the scriptures and realize their truth in a short time. In due course he became the best known Jain scholar of the time. He was like the illuminating lamp of the Jain order and therefore came to be known...

expounded on the nature of truth in the court of King Vikramāditya

Vikramaditya

Vikramaditya was a legendary emperor of Ujjain, India, famed for his wisdom, valour and magnanimity. The title "Vikramaditya" was later assumed by many other kings in Indian history, notably the Gupta King Chandragupta II and Samrat Hem Chandra Vikramaditya .The name King Vikramaditya is a...

:

In Sanmatitarka, Divākara further adds: "All doctrines are right in their own respective spheres—but if they encroach upon the province of other doctrines and try to refute their view, they are wrong. A man who holds the view of the cumulative character of truth never says that a particular view is right or that a particular view is wrong."

Age of logic

The period beginning with the start of common era, up to the modern period is often referred to as the age of logic in the history of Jain philosophyJain philosophy

Jain philosophy deals extensively with the problems of metaphysics, reality, cosmology, ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is essentially a transtheistic religion of ancient India. It is a continuation of the ancient tradition which co-existed with the Vedic tradition since ancient...

. By the time of Akalanka (5th century CE), whose works are a landmark in Jain logic, anekāntavāda was firmly entrenched in Jain texts, as is evident from the various teachings of the Jain scriptures.

Ācārya Haribhadra

Haribhadra

Haribhadra Suri was a Svetambara mendicant Jain leader and author.-History:There are multiple contradictory dates assigned to his birth. These include 459, 478, and 529. However, given his familiarity with Dharmakirti, a more likely choice would be sometime after 650...

(8th century CE) was one of the leading proponents of anekāntavāda. He was the first classical author to write a doxography

Doxography

Doxography is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term was coined by the German classical scholar Hermann Alexander Diels.- Classic Greek philosophy :...

, a compendium of a variety of intellectual views. This attempted to contextualise Jain thoughts within the broad framework, rather than espouse narrow partisan views. It interacted with the many possible intellectual orientations available to Indian thinkers around the 8th century.

Ācārya Amrtacandra starts his famous 10th century CE work Purusathasiddhiupaya with strong praise for anekāntavāda: "I bow down to the principle of anekānta, the source and foundation of the highest scriptures, the dispeller of wrong one-sided notions, that which takes into account all aspects of truth, reconciling diverse and even contradictory traits of all objects or entity."

Ācārya Vidyānandi (11th century CE) provides the analogy of the ocean to explain the nature of truth in Tattvarthaslokavārtikka, 116: "Water from the ocean contained in a pot can neither be called an ocean nor a non-ocean, but simply a part of ocean. Similarly, a doctrine, though arising from absolute truth can neither be called a whole truth nor a non-truth."

, a 17th century Jain monk, went beyond anekāntavāda by advocating madhāyastha, meaning "standing in the middle" or "equidistance". This position allowed him to praise qualities in others even though the people were non-Jain and belonged to other faiths. There was a period of stagnation after Yasovijayaji, as there were no new contributions to the development of Jain philosophy.

Role in ensuring the survival of Jainism

Anekāntavāda played a pivotal role in the growth as well as the survival of Jainism in ancient India, especially against onslaughts from Śaivas, Vaiṣṇavas, Buddhists, MuslimMuslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

s, and Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

s at various times. According to Hermann Jacobi

Hermann Jacobi

Hermann Georg Jacobi was an eminent German Indologist.-Education:Jacobi was born in Köln on 11 February 1850...

, Māhavīra

Mahavira

Mahāvīra is the name most commonly used to refer to the Indian sage Vardhamāna who established what are today considered to be the central tenets of Jainism. According to Jain tradition, he was the 24th and the last Tirthankara. In Tamil, he is referred to as Arukaṉ or Arukadevan...

used such concepts as syādvāda and saptbhangi to silence some of his opponents. The discussions of the agnostics led by had probably influenced many of their contemporaries and consequently syādvāda may have seemed to them a way out of ajñānavāda. Jacobi further speculates that many of their followers would have gone over to Māhavīra's creed, convinced of the truth of the saptbhanginaya. According to Professor Christopher Key Chapple, anekāntavāda allowed Jains to survive during the most hostile and unfavourable moments in history. According to John Koller, professor of Asian studies

Asian studies

Asian studies, a term used usually in the United States for Oriental studies and is concerned with the Asian peoples, their cultures, languages, history and politics...

, anekāntavāda allowed Jain thinkers to maintain the validity of their doctrine, while at the same time respectfully criticizing the views of their opponents.

Anekāntavāda was often used by Jain monks to obtain royal patronage from Hindu Kings. Ācārya Hemacandra

Acharya Hemachandra

Acharya Hemachandra was a Jain scholar, poet, and polymath who wrote on grammar, philosophy, prosody, and contemporary history. Noted as a prodigy by his contemporaries, he gained the title Kalikāl Sarvagya "all-knowing of the Kali Yuga"....

used anekāntavāda to gain the confidence and respect of the Cālukya

Solanki

The Solanki was a royal Hindu Indian dynasty that ruled parts of western and central India between the 10th to 13th centuries. A number of scholars including V. A. Smith assign them Gurjar origin....

Emperor Jayasimha Siddharaja. According to the Jain text Prabandhacantamani, Emperor Siddharaja desired enlightenment and liberation and he questioned teachers from various traditions. He remained in a quandary when he discovered that they all promoted their own teachings while disparaging other teachings. Among the teachers he questioned was Hemacandra, who, rather than promote Jainism, told him a story with a different message. According to his story, a sick man was cured of his disease after eating all the herbs available, as he was not aware which herb was medicinal. The moral of the tale, according to Hemacandra, was that just as the man was restored by the herb, even though no one knew which particular herb did the trick, so in the kaliyuga

Kali Yuga

Kali Yuga is the last of the four stages that the world goes through as part of the cycle of yugas described in the Indian scriptures. The other ages are Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga and Dvapara Yuga...

("age of vice") the wise should obtain salvation by supporting all religious traditions, even though no-one can say with absolute certainty which tradition it is that provides that salvation.

Influence

Jain religious tolerance fits well with the ecumenical disposition typical of Indian religions. It can be traced to the analogous Jain principles of anekāntavāda and . The epistemology of anekāntavāda and syādvāda also had a profound impact on the development of ancient Indian logic and philosophy. In recent times, Jainism influenced Gandhi, who advocated and satyagraha.Intellectual ahimsā and religious tolerance

The concepts of anekāntavāda and syādvāda allow Jains to accept the truth in other philosophies from their own perspective and thus inculcate tolerance for other viewpoints. Anekāntavāda is non-absolutist and stands firmly against all dogmatisms, including any assertion that JainismJainism

Jainism is an Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence towards all living beings. Its philosophy and practice emphasize the necessity of self-effort to move the soul towards divine consciousness and liberation. Any soul that has conquered its own inner enemies and achieved the state...

is the only correct religious path. It is thus an intellectual , or of the mind. Burch writes, "Jain logic is intellectual . Just as a right-acting person respects the life of all beings, so a right-thinking person acknowledges the validity of all judgments. This means recognizing all aspects of reality, not merely one or some aspects, as is done in non-Jain philosophies."

Māhavīra encouraged his followers to study and understand rival traditions in his Acaranga Sutra

Acaranga Sutra

The Acaranga Sutra is the first of the eleven Angas, part of the agamas which were compiled based on the teachings of Lord Mahavira.The Acaranga Sutra discusses the conduct of a Jain monk...

: "Comprehend one philosophical view through the comprehensive study of another one."

In anekāntavāda, there is no "battle of ideas", because this is considered to be a form of intellectual himsa or violence, leading quite logically to physical violence and war. In today's world, the limitations of the adversarial, "either with us or against us

You're either with us, or against us

The phrase "you're either with us, or against us" and similar variations are used to depict situations as being polarized and to force witnesses and bystanders to become allies or lose favor...

" form of argument are increasingly apparent by the fact that the argument leads to political, religious and social conflicts. Sūtrakrtānga

Sutrakritanga

Sutrakritanga Sutra is the second agama of the 12 main angās of the Jain canons. According to the Svetambara tradition it was written by Gandhara Sudharmasvami in Ardhamagadhi Prakrit...

, the second oldest canon of Jainism, provides a solution by stating: "Those who praise their own doctrines and ideology and disparage the doctrine of others distort the truth and will be confined to the cycle of birth and death."

This ecumenical and irenical attitude, engendered by anekāntavāda, allowed modern Jain monks such as Vijayadharmasuri to declare: "I am neither a Jain nor a Buddhist, a Vaisnava nor a Saivite, a Hindu

Hindu

Hindu refers to an identity associated with the philosophical, religious and cultural systems that are indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. As used in the Constitution of India, the word "Hindu" is also attributed to all persons professing any Indian religion...

nor a Muslim

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

, but a traveler on the path of peace shown by the supreme soul, the God who is free from passion."

Contemporary role and influence

Some modern authors believe that Jain philosophyJain philosophy

Jain philosophy deals extensively with the problems of metaphysics, reality, cosmology, ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is essentially a transtheistic religion of ancient India. It is a continuation of the ancient tradition which co-existed with the Vedic tradition since ancient...

in general and anekāntavāda in particular can provide a solution to many problems facing the world. They claim that even the mounting ecological crisis is linked to adversarialism, because it arises from a false division between humanity and "the rest" of nature. Modern judicial systems, democracy, freedom of speech

Freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship. The term freedom of expression is sometimes used synonymously, but includes any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used...

, and secularism

Secularism

Secularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

all implicitly reflect an attitude of anekāntavāda. Many authors, such as Kamla Jain, have claimed that the Jain tradition, with its emphasis on ahimsā and anekāntavāda, is capable of solving religious intolerance, terrorism

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

, wars, the depletion of natural resources, environmental degradation and many other problems. Referring to the September 11 attacks, John Koller believes that violence in society mainly exists due to faulty epistemology and metaphysics as well as faulty ethics. A failure to respect the life and views of others, rooted in dogmatic and mistaken knowledge and refusal to acknowledge the legitimate claims of different perspectives, leads to violent and destructive behavior. Koller suggests that anekāntavāda has a larger role to play in the world peace. According to Koller, because anekāntavāda is designed to avoid one-sided errors, reconcile contradictory viewpoints, and accept the multiplicity and relativity of truth, the Jain philosophy is in a unique position to support dialogue and negotiations amongst various nations and peoples.

Some Indologists like Professor John Cort have cautioned against giving undue importance to "intellectual " as the basis of anekāntavāda. He points out that Jain monks have also used anekāntavāda and syādvāda as debating weapons to silence their critics and prove the validity of the Jain doctrine over others. According to Dundas, in Jain hands, this method of analysis became a fearsome weapon of philosophical polemic

Polemic

A polemic is a variety of arguments or controversies made against one opinion, doctrine, or person. Other variations of argument are debate and discussion...

with which the doctrines of Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism is the predominant and indigenous religious tradition of the Indian Subcontinent. Hinduism is known to its followers as , amongst many other expressions...

and Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

could be pared down to their ideological bases of simple permanence and impermanence, respectively, and thus could be shown to be one-pointed and inadequate as the overall interpretations of reality they purported to be.Dundas, Paul (2002) p. 192 On the other hand, the many-sided approach was claimed by the Jains to be immune from criticism since it did not present itself as a philosophical or dogmatic view.

Influence on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Since childhood, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was exposed to the actual practice of non-violence, non-possession and anekāntavāda by his mother. According to biographers like Uma Majumdar, Rajmohan GandhiRajmohan Gandhi

Rajmohan Gandhi is a biographer and grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, and a research professor at the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.Gandhi's maternal grandfather was C...

, and Stephen Hay, these early childhood impressions and experiences contributed to the formation of Gandhi's character and his further moral and spiritual development. In his writings, Mahatma Gandhi attributed his seemingly contradictory positions over a period of time to the learning process, experiments with truth and his belief in anekāntavāda. He proclaimed that the duty of every individual is to determine what is personally true and act on that relative perception of truth. According to Gandhi, a satyagrahi

Satyagraha

Satyagraha , loosely translated as "insistence on truth satya agraha soul force" or "truth force" is a particular philosophy and practice within the broader overall category generally known as nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. The term "satyagraha" was conceived and developed by Mahatma...

is duty bound to act according to his relative truth, but at the same time, he is also equally bound to learn from truth held by his opponent. In response to a friend's query on religious tolerance, he responded in the journal "Young India

Young India

Young India was a weekly journal published in English by Mahatma Gandhi from 1919 to 1932. Gandhi wrote various quotations in this journal that inspired many. He used the Young India to spread his unique ideology and thoughts regarding independence....

- 21 Jan 1926":

Criticism

The doctrines of anekāntavāda and syādavāda are often criticised on the grounds that they engender a degree of hesitancy and uncertainty, and may compound problems rather than solve them. It is also pointed out that Jain epistemology asserts its own doctrines, but at the cost of being unable to deny contradictory doctrines. Furthermore, it is also argued that this doctrine could be self-defeating. It is argued that if reality is so complex that no single doctrine can describe it adequately, then anekāntavāda itself, being a single doctrine, must be inadequate. This criticism seems to have been anticipated by Ācārya Samantabhadra who said: "From the point of view of pramana (means of knowledge) it is anekānta (multi-sided), but from a point of view of naya (partial view) it is ekanta (one-sided)."In defense of the doctrine, Jains point out that anekāntavāda seeks to reconcile apparently opposing viewpoints rather than refuting them.

Adi Shankara

Adi Shankara Adi Shankara Adi Shankara (IAST: pronounced , (Sanskrit: , ) (788 CE - 820 CE), also known as ' and ' was an Indian philosopher from Kalady of present day Kerala who consolidated the doctrine of advaita vedānta...

(9th century C.E.). Sankara argued against some tenets of Jainism in his bhasya on Brahmasutra (2:2:33–36). His main arguments centre on anekāntavāda:

However, many believe that Sankara fails to address genuine anekāntavāda. By identifying syādavāda with sansayavāda, he instead addresses "agnosticism

Agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view that the truth value of certain claims—especially claims about the existence or non-existence of any deity, but also other religious and metaphysical claims—is unknown or unknowable....

", which was argued by . Many authors like Pandya believe that Sankara overlooked that, the affirmation of the existence of an object is in respect to the object itself, and its negation is in respect to what the object is not. Genuine anekāntavāda thus considers positive and negative attributes of an object, at the same time, and without any contradictions.

Another Buddhist logician Dharmakirti

Dharmakirti

Dharmakīrti , was an Indian scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian philosophical logic. He was one of the primary theorists of Buddhist atomism, according to which the only items considered to exist are momentary states of consciousness.-History:Born around the turn of the 7th century,...

ridiculed anekāntavāda in Pramānavarttikakārika: "With the differentiation removed, all things have dual nature. Then, if somebody is implored to eat curd, then why he does not eat camel?" The insinuation is obvious; if curd exists from the nature of curd and does not exist from the nature of a camel, then one is justified in eating camel, as by eating camel, he is merely eating the negation of curd. Ācārya Akalanka, while agreeing that Dharmakirti may be right from one viewpoint, took it upon himself to issue a rejoinder:

See also

- Buddhist philosophyBuddhist philosophyBuddhist philosophy deals extensively with problems in metaphysics, phenomenology, ethics, and epistemology.Some scholars assert that early Buddhist philosophy did not engage in ontological or metaphysical speculation, but was based instead on empirical evidence gained by the sense organs...

- ContextualismContextualismContextualism describes a collection of views in philosophy which emphasize the context in which an action, utterance, or expression occurs, and argues that, in some important respect, the action, utterance, or expression can only be understood relative to that context...

- Degrees of truth

- False dilemmaFalse dilemmaA false dilemma is a type of logical fallacy that involves a situation in which only two alternatives are considered, when in fact there are additional options...

- Fuzzy logicFuzzy logicFuzzy logic is a form of many-valued logic; it deals with reasoning that is approximate rather than fixed and exact. In contrast with traditional logic theory, where binary sets have two-valued logic: true or false, fuzzy logic variables may have a truth value that ranges in degree between 0 and 1...

- Hindu philosophyHindu philosophyHindu philosophy is divided into six schools of thought, or , which accept the Vedas as supreme revealed scriptures. Three other schools do not accept the Vedas as authoritative...

- Indian logicIndian logicThe development of Indian logic dates back to the anviksiki of Medhatithi Gautama the Sanskrit grammar rules of Pāṇini ; the Vaisheshika school's analysis of atomism ; the analysis of inference by Gotama , founder of the Nyaya school of Hindu philosophy; and the tetralemma of Nagarjuna...

- Logical disjunctionLogical disjunctionIn logic and mathematics, a two-place logical connective or, is a logical disjunction, also known as inclusive disjunction or alternation, that results in true whenever one or more of its operands are true. E.g. in this context, "A or B" is true if A is true, or if B is true, or if both A and B are...

- Logical equalityLogical equalityLogical equality is a logical operator that corresponds to equality in Boolean algebra and to the logical biconditional in propositional calculus...

- Logical valueLogical valueIn logic and mathematics, a truth value, sometimes called a logical value, is a value indicating the relation of a proposition to truth.In classical logic, with its intended semantics, the truth values are true and false; that is, classical logic is a two-valued logic...

- Multiplicities

- Multi-valued logicMulti-valued logicIn logic, a many-valued logic is a propositional calculus in which there are more than two truth values. Traditionally, in Aristotle's logical calculus, there were only two possible values for any proposition...

- PerspectivismPerspectivismPerspectivism is the philosophical view developed by Friedrich Nietzsche that all ideations take place from particular perspectives. This means that there are many possible conceptual schemes, or perspectives in which judgment of truth or value can be made...

- Principle of BivalencePrinciple of bivalenceIn logic, the semantic principle of bivalence states that every declarative sentence expressing a proposition has exactly one truth value, either true or false...

- Propositional logic

- RelativismRelativismRelativism is the concept that points of view have no absolute truth or validity, having only relative, subjective value according to differences in perception and consideration....

- Rhizome (philosophy)Rhizome (philosophy)Rhizome is a philosophical concept developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their Capitalism and Schizophrenia project...

- Value pluralism

External links

- Pravin K. Shah on Anekantvada

- http://www.jainworld.com/jainbooks/firstep-2/indianjaina-1-1.htmThe Indian-Jaina Dialectic of SyadvadaSyadvadaSyādvāda is the Doctrine of Postulation of Jainism. In other words, Syādvāda provides the body of teachings or instruction which one uses to derive a postulate or axiom. The starting assumption or postulate is given as saptabhanginaya, from which other statements are logically derived...

in Relation to Probability] by P.C. Mahalanobis, Dialectica 8, 1954, 95–111. - http://www.jainworld.com/jainbooks/firstep-2/sspredication.htmThe SyadvadaSyadvadaSyādvāda is the Doctrine of Postulation of Jainism. In other words, Syādvāda provides the body of teachings or instruction which one uses to derive a postulate or axiom. The starting assumption or postulate is given as saptabhanginaya, from which other statements are logically derived...

System of Predication] by J. B. S. Haldane, Sankhya 18, 195–200, 1957. - Anekantvada. The Pluralism Project at Harvard UniversityHarvard UniversityHarvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

.