William R. King

Encyclopedia

William Rufus DeVane King (April 7, 1786 – April 18, 1853) was the 13th Vice President of the United States

for about six weeks (1853), and earlier a U.S. Representative

from North Carolina

, Minister to France

, and a Senator

from Alabama

. He was a Unionist

and his contemporaries considered him to be a moderate on the issues of sectionalism, slavery, and westward expansion that would eventually lead to the American Civil War

. He helped draft the Compromise of 1850

. The only United States executive official to take the oath of office on foreign soil, King died of tuberculosis

after only 45 days in office. With the exceptions of John Tyler

and Andrew Johnson

—both of whom succeeded to the Presidency—he remains the shortest-serving Vice President.

, to William King and Margaret deVane, and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

in 1803. He was admitted to the bar in 1806 and began practice in Clinton, North Carolina

. King was a member of the North Carolina House of Commons from 1807 to 1809 and city solicitor of Wilmington, North Carolina

, in 1810. He was elected to the Twelfth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Congresses

, serving from March 4, 1811 until November 4, 1816, when he resigned. King was Secretary of the Legation

to William Pinkney

at Naples

, Italy

, and later at St. Petersburg, Russia

. He returned to the United States in 1818 and purchased property at what would later be known as King's Bend on the Alabama River

in Dallas County, Alabama

, between what is now Selma

and Cahaba

. There he established a large Black Belt

cotton plantation that he named Chestnut Hill. King and his relatives were reportedly one of the largest slave-holding

families in Alabama, collectively owning as many as five hundred slaves.

, and was reelected as a Jacksonian

in 1822, 1828, 1834, and 1841, serving from December 14, 1819, until April 15, 1844, when he resigned. He served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate

during the 24th through 27th Congresses. King was Chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Commerce.

He was Minister to France

from 1844 to 1846. He was appointed and subsequently elected as a Democrat to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Arthur P. Bagby

and began serving on July 1, 1848. During the conflicts leading up to the Compromise of 1850

, King supported the Senate's gag rule

against debate on antislavery petitions, and opposed the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. King supported a conservative proslavery position, arguing that the Constitution

protected the institution of slavery in both the Southern states and the federal territories, placing King in opposition to both the abolitionists'

efforts to abolish slavery in the territories and the Fire-Eaters'

calls for Southern secession

.

On July 11, 1850, just two days after the death of President Zachary Taylor

, King was again appointed President pro tempore of the Senate, which made him first in the line of succession to the U.S. Presidency

, because of the Vice Presidential vacancy

. King served until resigning on December 20, 1852, due to poor health. He served as President pro tempore of the Senate during the Thirty-first and Thirty-second Congresses and was Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations

and Committee on Pensions.

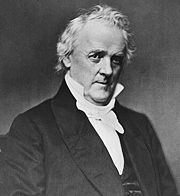

King was close friends with James Buchanan

King was close friends with James Buchanan

, and the two shared a house in Washington, D.C.

for fifteen years prior to Buchanan's presidency. Buchanan and King's close relationship prompted Andrew Jackson

to refer to King as "Miss Nancy" and "Aunt Fancy", while Aaron V. Brown

spoke of the two as "Buchanan and his wife". Further, some of the contemporary press also speculated about Buchanan and King's relationship. Buchanan and King's nieces destroyed their uncles' correspondence, leaving some questions as to what relationship the two men had, but surviving letters illustrate the affection of a special friendship, and Buchanan wrote of his communion with his housemate. Buchanan wrote in 1844, after King left for France, "I am now solitary and alone, having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone; and should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection." While the circumstances surrounding Buchanan and King have led authors such as Paul Boller to speculate that Buchanan was "America's first homosexual president", there is no direct evidence that he and King had a sexual relationship.

on the Democratic ticket with Franklin Pierce

in 1852 and took the oath of office on March 24, 1853, in Cuba

. He had gone to La Ariadne plantation, owned by John Chartrand, in Matanzas

due to his ill health. This unusual inauguration

took place because it was believed that King, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis

, would not live much longer. The privilege of taking the oath on foreign soil was extended by a special act of Congress for his long and distinguished service to the government of the United States. Even though he took the oath 20 days after the inauguration day, he was still Vice President during those three weeks.

Shortly afterward, King returned to his Chestnut Hill plantation and died within two days. He was interred in a vault on the plantation and later reburied in Selma's Live Oak Cemetery.

Following King's death the office of Vice-President remained vacant until 1857 when John C. Breckinridge

was inaugurated. In accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, the President pro tempore of the Senate

was next in order of succession to President Pierce from 1853 to 1857.

, a debating society at the university which still maintains an 1839 portrait (see above) of him at Phi Hall.

King was a co-founder of (and named) Selma, Alabama

. He named the Alabama River town after the Ossian

ic poem The Songs of Selma. In recognition of this, city officials in Selma and some of King's family wanted to move his body to Selma, where they believed King's remains should be interred. Other family members wanted his body to remain at Chestnut Hill. In 1882, the Selma City Council appointed a committee to select a new plot for King's body. There are different versions of how his body was taken from the plantation in King's Bend; however, after 29 years of interment at his former plantation, he was re-interred in the city's Live Oak Cemetery under an elaborate white marble mausoleum.

In honor of his election as Vice President, in December 1852 Oregon Territory

named King County

for him, as well as Pierce County

after President-elect Pierce. These counties became part of Washington Territory

when it was created the following year. Washington did not become a state until 1889, and Pierce and King counties still exist. Much later, King County amended its designation and its logo to honor Martin Luther King, Jr.

; the county's action was taken by ordinance

and was later reinforced in a statutory action (SB 5332, April 19, 2005) by the State of Washington.

|-

|-

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

for about six weeks (1853), and earlier a U.S. Representative

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

from North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

, Minister to France

United States Ambassador to France

This article is about the United States Ambassador to France. There has been a United States Ambassador to France since the American Revolution. The United States sent its first envoys to France in 1776, towards the end of the four-centuries-old Bourbon dynasty...

, and a Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

from Alabama

Alabama

Alabama is a state located in the southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Tennessee to the north, Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and Mississippi to the west. Alabama ranks 30th in total land area and ranks second in the size of its inland...

. He was a Unionist

Perpetual Union

The Perpetual Union is a feature of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which established the United States of America as a national entity...

and his contemporaries considered him to be a moderate on the issues of sectionalism, slavery, and westward expansion that would eventually lead to the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. He helped draft the Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

. The only United States executive official to take the oath of office on foreign soil, King died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

after only 45 days in office. With the exceptions of John Tyler

John Tyler

John Tyler was the tenth President of the United States . A native of Virginia, Tyler served as a state legislator, governor, U.S. representative, and U.S. senator before being elected Vice President . He was the first to succeed to the office of President following the death of a predecessor...

and Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

—both of whom succeeded to the Presidency—he remains the shortest-serving Vice President.

Early life

King was born in Sampson County, North CarolinaSampson County, North Carolina

-Demographics:As of the census of 2010, there were 63,431 people, 22,624 households, and 16,214 families residing in the county. The population density was 67.1 people per square mile . There were 26,476 housing units at an average density of 27 per square mile...

, to William King and Margaret deVane, and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is a public research university located in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States...

in 1803. He was admitted to the bar in 1806 and began practice in Clinton, North Carolina

Clinton, North Carolina

Clinton is the county seat of Sampson County, North Carolina, United States. The population of Clinton is 8,639 according to the 2010 US Census. Clinton is named for American Revolution General Richard Clinton.-History:...

. King was a member of the North Carolina House of Commons from 1807 to 1809 and city solicitor of Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington, North Carolina

Wilmington is a port city in and is the county seat of New Hanover County, North Carolina, United States. The population is 106,476 according to the 2010 Census, making it the eighth most populous city in the state of North Carolina...

, in 1810. He was elected to the Twelfth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Congresses

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

, serving from March 4, 1811 until November 4, 1816, when he resigned. King was Secretary of the Legation

Legation

A legation was the term used in diplomacy to denote a diplomatic representative office lower than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an Ambassador, a legation was headed by a Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary....

to William Pinkney

William Pinkney

William Pinkney was an American statesman and diplomat, and the seventh U.S. Attorney General.-Biography:Born in Annapolis, Maryland, Pinkney studied medicine and law, becoming a lawyer after his admission to the bar in 1786...

at Naples

Naples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, and later at St. Petersburg, Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

. He returned to the United States in 1818 and purchased property at what would later be known as King's Bend on the Alabama River

Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery.The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it unites with the Tombigbee, forming the Mobile and Tensaw rivers, which discharge into...

in Dallas County, Alabama

Dallas County, Alabama

Dallas County is a county of the U.S. state of Alabama. Its name is in honor of United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas. The county seat is Selma.- History :...

, between what is now Selma

Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, Alabama, United States, located on the banks of the Alabama River. The population was 20,512 at the 2000 census....

and Cahaba

Cahaba, Alabama

Cahaba, also spelled Cahawba, was the first permanent state capital of Alabama from 1820 to 1825. It is now a ghost town and state historic site. The site is located in Dallas County, southwest of Selma.-Capital:...

. There he established a large Black Belt

Black Belt (region of Alabama)

The Black Belt is a region of the U.S. state of Alabama, and part of the larger Black Belt Region of the Southern United States, which stretches from Texas to Maryland. The term originally referred to the region underlain by a thin layer of rich, black topsoil developed atop the chalk of the Selma...

cotton plantation that he named Chestnut Hill. King and his relatives were reportedly one of the largest slave-holding

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

families in Alabama, collectively owning as many as five hundred slaves.

Politics

King was a delegate to the convention which organized the Alabama state government. Upon the admission of Alabama as a State in 1819 he was elected as a Democratic-Republican to the United States SenateUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, and was reelected as a Jacksonian

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

in 1822, 1828, 1834, and 1841, serving from December 14, 1819, until April 15, 1844, when he resigned. He served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate

President pro tempore of the United States Senate

The President pro tempore is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate. The United States Constitution states that the Vice President of the United States is the President of the Senate and the highest-ranking official of the Senate despite not being a member of the body...

during the 24th through 27th Congresses. King was Chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Commerce.

He was Minister to France

United States Ambassador to France

This article is about the United States Ambassador to France. There has been a United States Ambassador to France since the American Revolution. The United States sent its first envoys to France in 1776, towards the end of the four-centuries-old Bourbon dynasty...

from 1844 to 1846. He was appointed and subsequently elected as a Democrat to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Arthur P. Bagby

Arthur P. Bagby

Arthur Pendleton Bagby was the tenth Governor of the U.S. state of Alabama from 1837 to 1841. Born in Louisa County, Virginia in 1794, he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1819, practicing in Claiborne, Alabama...

and began serving on July 1, 1848. During the conflicts leading up to the Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

, King supported the Senate's gag rule

Gag rule

A gag rule is a rule that limits or forbids the raising, consideration or discussion of a particular topic by members of a legislative or decision-making body.-Origin and pros and cons:...

against debate on antislavery petitions, and opposed the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. King supported a conservative proslavery position, arguing that the Constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

protected the institution of slavery in both the Southern states and the federal territories, placing King in opposition to both the abolitionists'

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

efforts to abolish slavery in the territories and the Fire-Eaters'

Fire-Eaters

In United States history, the term Fire-Eaters refers to a group of extremist pro-slavery politicians from the South who urged the separation of southern states into a new nation, which became known as the Confederate States of America.-Impact:...

calls for Southern secession

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

.

On July 11, 1850, just two days after the death of President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

, King was again appointed President pro tempore of the Senate, which made him first in the line of succession to the U.S. Presidency

United States presidential line of succession

The United States presidential line of succession defines who may become or act as President of the United States upon the incapacity, death, resignation, or removal from office of a sitting president or a president-elect.- Current order :This is a list of the current presidential line of...

, because of the Vice Presidential vacancy

Acting Vice President

Acting Vice President of the United States is an unofficial designation that has occasionally been used when the office of Vice President was vacant....

. King served until resigning on December 20, 1852, due to poor health. He served as President pro tempore of the Senate during the Thirty-first and Thirty-second Congresses and was Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations

United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It is charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. The Foreign Relations Committee is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid programs as...

and Committee on Pensions.

Relationship with James Buchanan

James Buchanan

James Buchanan, Jr. was the 15th President of the United States . He is the only president from Pennsylvania, the only president who remained a lifelong bachelor and the last to be born in the 18th century....

, and the two shared a house in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

for fifteen years prior to Buchanan's presidency. Buchanan and King's close relationship prompted Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

to refer to King as "Miss Nancy" and "Aunt Fancy", while Aaron V. Brown

Aaron V. Brown

Aaron Venable Brown was a Governor of Tennessee and Postmaster General in the Buchanan administration. He was also the law partner of James K. Polk.-Biography:...

spoke of the two as "Buchanan and his wife". Further, some of the contemporary press also speculated about Buchanan and King's relationship. Buchanan and King's nieces destroyed their uncles' correspondence, leaving some questions as to what relationship the two men had, but surviving letters illustrate the affection of a special friendship, and Buchanan wrote of his communion with his housemate. Buchanan wrote in 1844, after King left for France, "I am now solitary and alone, having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone; and should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection." While the circumstances surrounding Buchanan and King have led authors such as Paul Boller to speculate that Buchanan was "America's first homosexual president", there is no direct evidence that he and King had a sexual relationship.

Vice Presidency and death

King was elected Vice President of the United StatesVice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

on the Democratic ticket with Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce was the 14th President of the United States and is the only President from New Hampshire. Pierce was a Democrat and a "doughface" who served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Pierce took part in the Mexican-American War and became a brigadier general in the Army...

in 1852 and took the oath of office on March 24, 1853, in Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

. He had gone to La Ariadne plantation, owned by John Chartrand, in Matanzas

Matanzas

Matanzas is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas. It is famed for its poets, culture, and Afro-Cuban folklore.It is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Matanzas , east of the capital Havana and west of the resort town of Varadero.Matanzas is called the...

due to his ill health. This unusual inauguration

Inauguration

An inauguration is a formal ceremony to mark the beginning of a leader's term of office. An example is the ceremony in which the President of the United States officially takes the oath of office....

took place because it was believed that King, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

, would not live much longer. The privilege of taking the oath on foreign soil was extended by a special act of Congress for his long and distinguished service to the government of the United States. Even though he took the oath 20 days after the inauguration day, he was still Vice President during those three weeks.

Shortly afterward, King returned to his Chestnut Hill plantation and died within two days. He was interred in a vault on the plantation and later reburied in Selma's Live Oak Cemetery.

Following King's death the office of Vice-President remained vacant until 1857 when John C. Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

was inaugurated. In accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, the President pro tempore of the Senate

President pro tempore of the United States Senate

The President pro tempore is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate. The United States Constitution states that the Vice President of the United States is the President of the Senate and the highest-ranking official of the Senate despite not being a member of the body...

was next in order of succession to President Pierce from 1853 to 1857.

Legacy

The King Residence Quadrangle at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, his alma mater, is named in William R. King's honor, and is the site of Mangum, Manly, Ruffin and Grimes house residences. King also maintained membership in The Dialectic and Philanthropic SocietiesThe Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies

The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, commonly known as Di-Phi, are the debate and literary societies of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.- History :...

, a debating society at the university which still maintains an 1839 portrait (see above) of him at Phi Hall.

King was a co-founder of (and named) Selma, Alabama

Selma, Alabama

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, Alabama, United States, located on the banks of the Alabama River. The population was 20,512 at the 2000 census....

. He named the Alabama River town after the Ossian

Ossian

Ossian is the narrator and supposed author of a cycle of poems which the Scottish poet James Macpherson claimed to have translated from ancient sources in the Scots Gaelic. He is based on Oisín, son of Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill, anglicised to Finn McCool, a character from Irish mythology...

ic poem The Songs of Selma. In recognition of this, city officials in Selma and some of King's family wanted to move his body to Selma, where they believed King's remains should be interred. Other family members wanted his body to remain at Chestnut Hill. In 1882, the Selma City Council appointed a committee to select a new plot for King's body. There are different versions of how his body was taken from the plantation in King's Bend; however, after 29 years of interment at his former plantation, he was re-interred in the city's Live Oak Cemetery under an elaborate white marble mausoleum.

In honor of his election as Vice President, in December 1852 Oregon Territory

Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Originally claimed by several countries , the region was...

named King County

King County, Washington

King County is a county located in the U.S. state of Washington. The population in the 2010 census was 1,931,249. King is the most populous county in Washington, and the 14th most populous in the United States....

for him, as well as Pierce County

Pierce County, Washington

right|thumb|[[Tacoma, Washington|Tacoma]] - Seat of Pierce CountyPierce County is the second most populous county in the U.S. state of Washington. Formed out of Thurston County on December 22, 1852, by the legislature of Oregon Territory...

after President-elect Pierce. These counties became part of Washington Territory

Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 8, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington....

when it was created the following year. Washington did not become a state until 1889, and Pierce and King counties still exist. Much later, King County amended its designation and its logo to honor Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the...

; the county's action was taken by ordinance

Local ordinance

A local ordinance is a law usually found in a municipal code.-United States:In the United States, these laws are enforced locally in addition to state law and federal law.-Japan:...

and was later reinforced in a statutory action (SB 5332, April 19, 2005) by the State of Washington.

External links

- Who is William Rufus King?

- Obituary addresses on the occasion of the death of the Hon. William R. King, of Alabama, vice-president of the United States : delivered in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, eighth of December, 1853

|-

|-