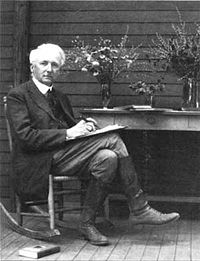

Robert Sterling Yard

Encyclopedia

Wilderness

Wilderness or wildland is a natural environment on Earth that has not been significantly modified by human activity. It may also be defined as: "The most intact, undisturbed wild natural areas left on our planet—those last truly wild places that humans do not control and have not developed with...

activist. Born in Haverstraw, New York

Haverstraw (town), New York

Haverstraw is a town in Rockland County, New York, United States located north of the Town of Clarkstown and the Town of Ramapo; east of Orange County, New York; south of the Town of Stony Point and west of the Hudson River. The town runs from the west to the east border of the county in its...

, Yard graduated from Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

and spent the first twenty years of his career in the editing and publishing business. In 1915, he was recruited by his friend Stephen Mather to help publicize the need for an independent national park agency. Their numerous publications were part of a movement that resulted in legislative support for a National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

(NPS) in 1916. Yard served as head of the National Parks Educational Committee for several years after its conception, but tension within the NPS led him to concentrate on non-government initiatives. He became executive secretary of the National Parks Association

National Parks Conservation Association

The National Parks Conservation Association is the only independent, membership organization devoted exclusively to advocacy on behalf of the National Parks System...

in 1919.

Yard worked to promote the national parks as well as educate Americans about their use. Creating high standards based on aesthetic ideals for park selection, he also opposed commercialism and industrialization of what he called "America's masterpieces". These standards subsequently caused discord with his peers. After helping to establish a relationship between the NPA and the United States Forest Service

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 155 national forests and 20 national grasslands, which encompass...

, Yard later became involved in the protection of wilderness areas. In 1935, he became one of the eight founding members of The Wilderness Society

The Wilderness Society (United States)

The Wilderness Society is an American organization that is dedicated to protecting America's wilderness. It was formed in 1935 and currently has over 300,000 members and supporters.-Founding:The society was incorporated on January 21, 1935...

and acted as its first president from 1937 until his death eight years later. Yard is now considered an important figure in the modern wilderness movement.

Early life and career

Robert Sterling Yard was born in 1861 in Haverstraw, New YorkHaverstraw (town), New York

Haverstraw is a town in Rockland County, New York, United States located north of the Town of Clarkstown and the Town of Ramapo; east of Orange County, New York; south of the Town of Stony Point and west of the Hudson River. The town runs from the west to the east border of the county in its...

to Robert Boyd and Sarah (Purdue) Yard. After attending the Freehold Institute in New Jersey, he graduated from Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

in 1883. Known throughout his life as "Bob", he became a prominent member of Princeton's Alumni Association, and founded the Montclair

Montclair, New Jersey

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 38,977 people, 15,020 households, and 9,687 families residing in the township. The population density was 6,183.6 people per square mile . There were 15,531 housing units at an average density of 2,464.0 per square mile...

Princeton Alumni Association. In 1895, he married Mary Belle Moffat; they had one daughter, Margaret.

During the 1880s and 1890s, Yard worked as a journalist for the New York Sun and the New York Herald

New York Herald

The New York Herald was a large distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between May 6, 1835, and 1924.-History:The first issue of the paper was published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., on May 6, 1835. By 1845 it was the most popular and profitable daily newspaper in the UnitedStates...

. He served in the publishing business from 1900 to 1915, variously as editor-in-chief of The Century Magazine

The Century Magazine

The Century Magazine was first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City as a successor to Scribner's Monthly Magazine...

and Sunday editor of the New York Herald. After serving as editor of Charles Scribner's Sons

Charles Scribner's Sons

Charles Scribner's Sons, or simply Scribner, is an American publisher based in New York City, known for publishing a number of American authors including Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Stephen King, Robert A. Heinlein, Thomas Wolfe, George Santayana, John Clellon...

' the Book Buyer, Yard helped launch the publishing firm of Moffat, Yard and Company. He served as vice president and editor-in-chief of the firm.

National Park Service

In 1915, Yard was invited to Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

by his friend Stephen Mather, who had started working on national parks as assistant to the Secretary of Interior. Yard and Mather had met while working for the New York Sun and became friends; Yard was the best man at Mather's wedding in 1893.

Mather, who wanted someone to help publicize the need for an independent agency to oversee the national parks movement, personally paid Yard's salary from his independent income. The United States had authorized 14 parks and 22 monuments over the previous forty years (1872–1915), but there was no single agency to provide unified management of the resources. In addition, some resources were managed by political appointees without professional qualifications. Together Mather and Yard ran a national parks publicity campaign for the Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior is the United States federal executive department of the U.S. government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land and natural resources, and the administration of programs relating to Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native...

, writing numerous articles that praised the scenic qualities of the parks and their possibilities for educational, inspirational and recreational benefits. The unprecedented press coverage persuaded influential Americans about the importance of national parks, and encouraged Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

to create an independent parks agency.

Although Yard was not an outdoorsman like most advocates of a national park service, he felt a connection to the cause, and eventually became personally invested in its success. At the National Park Conference in March 1915, he stated, "I, the treader of dusty city streets, boldly claim common kinship with you of the plains, the mountains, and the glaciers." He gathered data regarding popular American tourist destinations, such as Switzerland, France, Germany, Italy, and Canada, together with reasons why people visited certain areas; he also collected photographs and compiled lists of those who might enlist in the conservation cause. One of his most recognized and passionate articles of the time, entitled "Making a Business of Scenery", appeared in The Nation's Business in June 1916:

Yard's most successful publicity initiative during this time was the National Parks Portfolio (1916), a collection of nine pamphlets that—through photographs interspersed with text lauding the scenic grandeur of the nation's major parks—connected the parks with a sense of national identity to make visitation an imperative of American citizenship. Yard and Mather distributed this publication to a carefully selected list of prominent Americans, including every member of Congress. That same year, Yard wrote and published Glimpses of Our National Parks, which was followed in 1917 by a similar volume titled The Top of the Continent. The latter volume, which was subtitled A Cheerful Journey through Our National Parks and geared toward a younger audience, became a bestseller.

Yard and Mather's publicity and lobbying resulted in the creation of the National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

; on August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

signed a bill establishing the agency "to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and wild life therein, and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." Mather served as its first director beginning in 1917, and while he appointed Horace Albright

Horace M. Albright

Horace Marden Albright was an American conservationist.Horace Albright was born 1890 in Bishop, California, the son of George Albright, a miner. He graduated from University of California, Berkeley in 1912 , and earned a law degree from Georgetown University...

as assistant director, he put Yard in charge of the National Parks Educational Committee. Consisting only of Yard and a secretary, this division of the NPS produced informative publicity in order to draw visitors to parks and develop programs to enhance the educational value of their experience.

In January 1917, Mather suffered a mental breakdown

Mental breakdown

Mental breakdown is a non-medical term used to describe an acute, time-limited phase of a specific disorder that presents primarily with features of depression or anxiety.-Definition:...

and had to take an extended leave. Yard believed he would be appointed interim director at the NPS. Disagreements within the organization, however, kept him from the position. Yard, who has been described as "intense, urbane and opinionated", was disappointed when the position was given to Albright, who was then only 27 years old. After more than a year of working in the Educational Division, Yard began to look outside the NPS for support.

National Parks Association

Yard believed that while the National Park Service was effective as a government agency, it was not capable of promoting the wishes of the common American. He wrote in June 1918 that the national park movement must "be cultivated only by an organization of the people outside the government, and unhampered by politics and routine". On May 29, 1919, the National Parks AssociationNational Parks Conservation Association

The National Parks Conservation Association is the only independent, membership organization devoted exclusively to advocacy on behalf of the National Parks System...

(NPA) was officially created to fill this role. Yard, who became a pivotal figure in the new society, was elected its executive secretary. His duties as the only full-time employee of the NPA were practically the same as they had been with the NPS—to promote the national parks and to educate Americans about their use. In its early years, the NPA was Yard's livelihood and passion: he recruited the key founding members, raised money and wrote various press releases. Yard also served as editor of the NPA's National Parks Bulletin from 1919 to 1936. In the first issue, Yard outlined the organization's objectives in order to craft a broad educational program: not only would they attract students, artists and writers to the parks, but a "complete and rational system" would be created and adhered to by Congress and the Park Service.

Yard believed that eligible national parks had to be scenically stunning. He noted in his 1919 volume The Book of the National Parks that the major characteristic of almost all national parks was that their scenery had been forged by geological or biological processes. He wrote, "[W]e shall not really enjoy our possession of the grandest scenery in the world until we realize that scenery is the written page of the History of Creation, and until we learn to read that page." Yard's standards also insisted upon "complete conservation", meaning avoidance of commercialism and industrialization. Often referring to parks as "American masterpieces", he sought to protect them from economic activities such as timber cutting and mineral extracting. In such, Yard often advocated the preservation of "wilderness

Wilderness

Wilderness or wildland is a natural environment on Earth that has not been significantly modified by human activity. It may also be defined as: "The most intact, undisturbed wild natural areas left on our planet—those last truly wild places that humans do not control and have not developed with...

" conditions in America's national parks.

In 1920, Congress passed the Water Power Act

Federal Power Act

The Federal Power Act is a law appearing in Chapter 12 of Title 16 of the United States Code, entitled "Federal Regulation and Development of Power". Enacted as the Federal Water Power Act on June 10, 1920, and amended many times since, its original purpose was to more effectively coordinate the...

, which granted licenses to develop hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity is the term referring to electricity generated by hydropower; the production of electrical power through the use of the gravitational force of falling or flowing water. It is the most widely used form of renewable energy...

projects on federal lands, including national parks. Yard and the NPA joined again with Mather and the National Park Service to oppose the intrusion on Park Service control. In 1921, Congress passed the Jones-Esch Bill, amending the Water Power Act to exclude existing national parks from hydroelectric development.

Conflict and the Forest Service

Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park is a United States National Park spanning eastern portions of Tuolumne, Mariposa and Madera counties in east central California, United States. The park covers an area of and reaches across the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain chain...

in 1926, he stated that the valley was "lost" after he found crowds, automobiles, jazz music and a bear show.

In 1924, the United States Forest Service

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 155 national forests and 20 national grasslands, which encompass...

started a program to set aside "primitive areas" in the national forests to protect wilderness while opening it to use. Yard, who preferred to give the land that did not meet his standards to the Forest Service rather than the NPS, began to work closely with the USFS. Beginning in 1925, he served as secretary of the Joint Committee on the Recreational Survey of Federal Lands, a position he held until 1930. Composed of members of both the NPA and the USFS, the committee sought a separate national recreation policy that would distinguish between recreational and preservation areas. The NPA and Yard were both criticized by activists who feared that the association would be eclipsed by the Forest Service's own program goals. Yard at times felt isolated and under-appreciated by his peers. He wrote in 1926, "I wonder whether I'm justified in forcing this work upon people who seem to care so little about it."

By the late 1920s, Yard had come to believe preservation of wilderness was a solution to more commercially motivated park making. He continued to clash with others regarding legislation on park proposals. These included the Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park encompasses part of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the U.S. state of Virginia. This national park is long and narrow, with the broad Shenandoah River and valley on the west side, and the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont on the east...

in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, which Yard thought was too recreational and not of the caliber of a national park. He hesitated at the nomination of the Everglades National Park

Everglades National Park

Everglades National Park is a national park in the U.S. state of Florida that protects the southern 25 percent of the original Everglades. It is the largest subtropical wilderness in the United States, and is visited on average by one million people each year. It is the third-largest...

in Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

. When the Tropic Everglades National Park Association was founded in 1928 to promote the idea of a national park in south Florida, Yard was initially skeptical that it was necessary. Although he recognized the need for preservation, he did not accept proposals for a national park unless the area met his high scenic standards. He slowly warmed to the Everglades idea, and in 1931 supported the proposal under conditions that the area remain pristine, with limited tourist development. The Everglades National Park was authorized by Congress in 1934.

The Wilderness Society

Yard's preservationist goals exceeded those of the Park Service in the 1930s. Drifting away from the national parks lobby, he pushed to preserve what he called "primitive" land; he and John C. MerriamJohn C. Merriam

John Campbell Merriam was an American paleontologist. The first vertebrate paleontologist on the West Coast of the United States, he is best known for his taxonomy of vertebrate fossils at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, particularly with the genus Smilodon, more commonly known as the...

had discussed forming a group called "Save the Primitive League". Although that group was not formed, Yard was soon invited to become a founding member of The Wilderness Society

The Wilderness Society (United States)

The Wilderness Society is an American organization that is dedicated to protecting America's wilderness. It was formed in 1935 and currently has over 300,000 members and supporters.-Founding:The society was incorporated on January 21, 1935...

. Seventy-four-years old at the time, he was known for his tireless work ethic and youthfulness; for decades he had jokingly insisted to colleagues that he was a mere 47.

The society was officially formed in January 1935 to lead wilderness preservation in the United States. Additional founding members included notable conservationists Bob Marshall

Bob Marshall (wilderness activist)

Robert "Bob" Marshall was an American forester, writer and wilderness activist. The son of wealthy constitutional lawyer and conservationist Louis Marshall, Bob Marshall developed a love for the outdoors as a young child...

, Benton MacKaye

Benton MacKaye

Benton MacKaye was an American forester, planner and conservationist. He was born in Stamford, Connecticut; his father was actor and dramatist Steele MacKaye. After studying forestry at Harvard University , Benton later taught there for several years. He joined a number of Federal bureaus and...

, Bernard Frank

Bernard Frank (wilderness activist)

Bernard Frank was an American forester and wilderness activist. He is known for being one of the eight founding members of The Wilderness Society....

and Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold was an American author, scientist, ecologist, forester, and environmentalist. He was a professor at the University of Wisconsin and is best known for his book A Sand County Almanac , which has sold over two million copies...

. In September, Yard published the first issue of the society's magazine, The Living Wilderness. He wrote of the society's genesis, "The Wilderness Society is born of an emergency in conservation which admits of no delay. The craze is to build all the highways possible everywhere while billions may yet be borrowed from the unlucky future. The fashion is to barber and manicure wild America as smartly as the modern girl. Our mission is clear."

Although Marshall proposed that Leopold act as the society's first president, in 1937 Yard accepted the role, as well as that of permanent secretary. He ran the society from his home in Washington, D.C. and single-handedly produced The Living Wilderness during its early years, with one issue annually until 1945. Yard did the greater share of work during the Society's early years; he solicited membership, corresponded with other conservation groups, and kept track of congressional activities related to wilderness areas. Although much older than some of his colleagues, Yard was described as a cautious and non-confrontational leader.

Death and legacy

While ill from pneumonia at the end of his life, he ran the society's affairs from his bed. He died on May 17, 1945, at the age of 84.The National Park Service and what is now called the National Parks Conservation Association remain successful organizations. The National Park System of the United States comprises 390 areas covering more than 84 million acres (339,936.2 km²) in 49 states, Washington, D.C., American Samoa

American Samoa

American Samoa is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the sovereign state of Samoa...

, Guam

Guam

Guam is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States located in the western Pacific Ocean. It is one of five U.S. territories with an established civilian government. Guam is listed as one of 16 Non-Self-Governing Territories by the Special Committee on Decolonization of the United...

, Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

, Saipan

Saipan

Saipan is the largest island of the United States Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands , a chain of 15 tropical islands belonging to the Marianas archipelago in the western Pacific Ocean with a total area of . The 2000 census population was 62,392...

, and the Virgin Islands

Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands are the western island group of the Leeward Islands, which are the northern part of the Lesser Antilles, which form the border between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean...

. His work to preserve wilderness in the United States has also endured. After his death, three members of The Wilderness Society took on his various duties; Benton MacKaye

Benton MacKaye

Benton MacKaye was an American forester, planner and conservationist. He was born in Stamford, Connecticut; his father was actor and dramatist Steele MacKaye. After studying forestry at Harvard University , Benton later taught there for several years. He joined a number of Federal bureaus and...

officially replaced him as president, but executive secretary Howard Zahniser

Howard Zahniser

Howard Clinton Zahniser was an American environmental activist. Zahniser is noted for being the primary author of the Wilderness Act of 1964....

and director Olaus Murie

Olaus Murie

Olaus Murie , called the "father of modern elk management", was a naturalist, author, and wildlife biologist who did groundbreaking field research on a variety of large northern mammals. He also served as president of The Wilderness Society, The Wildlife Society, and as director of the Izaak Walton...

ran the society for the next two decades. Zahniser also took over the society's magazine, making The Living Wilderness into a successful quarterly publication.

The December 1945 issue of The Living Wilderness was dedicated to Yard's life and work; in one article, fellow co-founder Ernest Oberholtzer

Ernest Oberholtzer

Ernest Carl Oberholtzer was an American explorer, author and conservationist.Nicknamed "Ober", he was born and raised in Davenport, Iowa, but he lived most of his adult life in Minnesota. Oberholtzer attended Harvard University and received a bachelor of arts degree, but left after one year of...

wrote that "the form he [Yard] gave The Wilderness Society was the crowning of a life-long vision. He undertook it with a freshness that belied his years and revealed, as nothing else could, the vitality of his inspiration. Few men in America have ever had such understanding of the spiritual quality of the American scene, and fewer still the voice to go with it."

Yard's effect on the Wilderness Society proved long-lasting; he was responsible for initiating cooperation with other major preservationist groups, including the National Park Association. He also established a durable alliance with the Sierra Club

Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is the oldest, largest, and most influential grassroots environmental organization in the United States. It was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by the conservationist and preservationist John Muir, who became its first president...

, founded in 1892 by noted preservationist John Muir

John Muir

John Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions...

. This alliance proved crucial during the proposal and eventual passage of the Wilderness Act

Wilderness Act

The Wilderness Act of 1964 was written by Howard Zahniser of The Wilderness Society. It created the legal definition of wilderness in the United States, and protected some 9 million acres of federal land. The result of a long effort to protect federal wilderness, the Wilderness Act was signed...

. The act, which was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

on September 3, 1964, was the first major victory for The Wilderness Society. Written by Zahniser, it enabled Congress to set aside selected areas in the national forests, national parks, national wildlife refuges and other federal lands, as units to be kept permanently unchanged by humans. Since its conception, The Wilderness Society has contributed a total of 104 million acres (421,000 km²) to the National Wilderness Preservation System

National Wilderness Preservation System

The National Wilderness Preservation System of the United States protects federally managed land areas designated for preservation in their natural condition. It was established by the Wilderness Act upon the signature of President Lyndon B. Johnson on September 3, 1964...

.

Selected list of works

- The Publisher (1913)

- Glimpses of Our National Parks (1916)

- The Top of the Continent (1917)

- The Book of the National Parks (1919)

- The National Parks Portfolio (1921)

- Our Federal Lands: A Romance of American Development (1928)