Robert Boothby

Encyclopedia

Robert John Graham Boothby, Baron Boothby, KBE

(also known as Bob Boothby, 12 February 1900 – 16 July 1986) was a controversial British Conservative

politician.

, KBE, of Edinburgh

and a cousin of Rosalind Kennedy, mother of the broadcaster

Sir Ludovic Kennedy

, Boothby was educated at Eton College

and Magdalen College, Oxford

. He became a partner in a firm of stockbrokers.

in 1923 and was elected as Member of Parliament

(MP) for East Aberdeenshire

in 1924, holding the seat until 1958. He was Parliamentary Private Secretary

to Chancellor of the Exchequer

Winston Churchill

from 1926 to 1929 and held junior ministerial office as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food

in 1940–41. He was later forced to resign his post and go to the back benches for not declaring an interest when asking a parliamentary question. During World War II

, he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

, retiring with the rank of Flight Lieutenant

.

Boothby advocated the UK

's entry into the European Community (now the European Union

) and was a British delegate to the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe

from 1949 until 1957. He was a prominent commentator on public affairs on radio and television, often taking part in the long-running BBC

radio programme Any Questions. He also advocated the virtues of herring

as a food.

He was Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Economic Affairs, 1952–56; Honorary President of the Scottish Chamber of Agriculture, 1934, Rector of the University of St Andrews

, 1958–61; Chairman of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

, 1961–63, and President, Anglo-Israel

Association, 1962–75. He was awarded an Honorary LLD by St Andrews, 1959 and was made an Honorary Burgess of the Burghs of Peterhead

, Fraserburgh

, Turriff

and Rosehearty

. He was appointed an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1950, a KBE

in 1953.

Boothby was raised to the peerage as a life peer

with the title Baron Boothby, of Buchan

and Rattray Head

in the County of Aberdeen

, on 22 August 1958.

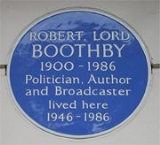

There is a blue plaque

on his house in Eaton Square

, London.

– whose reliability has been questioned – claimed after the death of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

that she had confided to him in a 1991 interview that "The press knew all about it", referring to Boothby's affairs, and that she described him as "a bounder but not a cad".

He was married twice: in 1935 to Diana Cavendish (marriage dissolved in 1937) and in 1967 to Wanda Sanna, a Sardinian woman, 33 years his junior. The writer and broadcaster Sir Ludovic Kennedy

has asserted that Boothby fathered at least three children by the wives of other men (two by one woman, one by another)."

From 1930 he had a long affair with Dorothy Macmillan, wife of the Conservative politician Harold Macmillan

(who would serve as prime minister from 1957 until 1963). He was rumoured to be father of the youngest Macmillan daughter, Sarah, though Harold Macmillan's most recent biographer D. R. Thorpe discounts Boothby's paternity. This connection to Macmillan, via his wife, has been seen as one of the reasons why the police didn't investigate the death of Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire

, who died in the presence of suspected serial killer

Dr John Bodkin Adams

. The duke was Lady Dorothy's brother, and it is thought the police were wary of drawing press attention to her while she was being unfaithful.

, Boothby earned the nickname "the Palladium

", because "he was twice nightly". He later spoke about the role of a speculated homosexual relationship in the drowning of his friend Michael Llewelyn Davies (one of the models for Peter Pan

) and fellow Oxonian Rupert Buxton. He did not start to have physical relationships with women until the age of 25. From 1954 he campaigned publicly for homosexual law reform.

In 1963 Boothby began an illicit affair with East End cat burglar Leslie Holt (d. 1979), a younger man he met at a gambling club. Holt introduced him to the gangster Ronald Kray, the younger Kray twin

, who supplied Boothby with young men and arranged orgies in Cedra Court, receiving personal favours from Boothby in return. When Boothby's underworld associations came to the attention of the Sunday Express, the Conservative

-supporting paper opted not to publish the damaging story. The matter was eventually reported in 1964 in the Labour-supporting Sunday Mirror

tabloid, and the parties subsequently named by the German magazine Stern

.

Boothby denied the story and threatened to sue the Mirror, and because his close homosexual friend, Tom Driberg

, a senior Labour

MP, was also involved in the criminal ring, neither of the major political parties had an interest in publicity, and the paper's owner, Cecil King

, came under pressure from the Labour leadership to drop the matter, to protect Driberg. The Mirror backed down, sacked its editor, apologised, and paid Boothby £40,000 in an out-of-court settlement. Consequently other newspapers became less willing to cover the Krays' criminal activities, which continued unchecked for three more years. The police investigation received no support from Scotland Yard

, while Boothby embarrassed his fellow peers by campaigning on behalf of the Krays in the Lords

, until their increasing violence made association impossible. It has been claimed that journalists who investigated Boothby were subjected to legal threats and break-ins, and that much of this suppression was directed by Arnold Goodman

.

aged 86, Boothby's ashes were scattered at Rattray Head

near Crimond

, Aberdeenshire

.

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

(also known as Bob Boothby, 12 February 1900 – 16 July 1986) was a controversial British Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

politician.

Early life

The only son of Sir Robert Tuite BoothbyRobert Tuite Boothby

Sir Robert Tuite Boothby KBE was a British banker.-Career:Boothby studied at the University of St Andrews. He was the manager of the Scottish Provident Institution from 1920 to 1940, and a director of the Bank of Scotland...

, KBE, of Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

and a cousin of Rosalind Kennedy, mother of the broadcaster

Presenter

A presenter, or host , is a person or organization responsible for running an event. A museum or university, for example, may be the presenter or host of an exhibit. Likewise, a master of ceremonies is a person that hosts or presents a show...

Sir Ludovic Kennedy

Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy was a British journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author best known for re-examining cases such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and the murder convictions of Timothy Evans and Derek Bentley, and for his role in the abolition of the death penalty in the United...

, Boothby was educated at Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

and Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2006 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £153 million. Magdalen is currently top of the Norrington Table after over half of its 2010 finalists received first-class degrees, a record...

. He became a partner in a firm of stockbrokers.

Politics

He was an unsuccessful parliamentary candidate for Orkney and ShetlandOrkney and Shetland (UK Parliament constituency)

Orkney and Shetland is a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system of election...

in 1923 and was elected as Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP) for East Aberdeenshire

East Aberdeenshire (UK Parliament constituency)

East Aberdeenshire was a Scottish county constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1868 to 1918 and form 1950 to 1983...

in 1924, holding the seat until 1958. He was Parliamentary Private Secretary

Parliamentary Private Secretary

A Parliamentary Private Secretary is a role given to a United Kingdom Member of Parliament by a senior minister in government or shadow minister to act as their contact for the House of Commons; this role is junior to that of Parliamentary Under-Secretary, which is a ministerial post, salaried by...

to Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

from 1926 to 1929 and held junior ministerial office as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food

Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food

The Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Food Control, later the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Food was a junior Ministerial post in the Government of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1921 and then from 1939 to 1954...

in 1940–41. He was later forced to resign his post and go to the back benches for not declaring an interest when asking a parliamentary question. During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve consists of a number of groupings of individual military reservists for the management and operation of the Royal Air Force's Air Training Corps and CCF Air Cadet formations, Volunteer Gliding Squadrons , Air Experience Flights, and also to form the...

, retiring with the rank of Flight Lieutenant

Flight Lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many Commonwealth countries. It ranks above flying officer and immediately below squadron leader. The name of the rank is the complete phrase; it is never shortened to "lieutenant"...

.

Boothby advocated the UK

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

's entry into the European Community (now the European Union

European Union

The European Union is an economic and political union of 27 independent member states which are located primarily in Europe. The EU traces its origins from the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Economic Community , formed by six countries in 1958...

) and was a British delegate to the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe is an international organisation promoting co-operation between all countries of Europe in the areas of legal standards, human rights, democratic development, the rule of law and cultural co-operation...

from 1949 until 1957. He was a prominent commentator on public affairs on radio and television, often taking part in the long-running BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

radio programme Any Questions. He also advocated the virtues of herring

Herring

Herring is an oily fish of the genus Clupea, found in the shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and the North Atlantic oceans, including the Baltic Sea. Three species of Clupea are recognized. The main taxa, the Atlantic herring and the Pacific herring may each be divided into subspecies...

as a food.

He was Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Economic Affairs, 1952–56; Honorary President of the Scottish Chamber of Agriculture, 1934, Rector of the University of St Andrews

Rector of the University of St Andrews

The Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews is a university official chosen every three years by the students of the University of St Andrews...

, 1958–61; Chairman of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It tours widely, and is sometimes referred to as "Britain's national orchestra"...

, 1961–63, and President, Anglo-Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

Association, 1962–75. He was awarded an Honorary LLD by St Andrews, 1959 and was made an Honorary Burgess of the Burghs of Peterhead

Peterhead

Peterhead is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is Aberdeenshire's biggest settlement , with a population of 17,947 at the 2001 Census and estimated to have fallen to 17,330 by 2006....

, Fraserburgh

Fraserburgh

Fraserburgh is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland with a population recorded in the 2001 Census at 12,454 and estimated at 12,630 in 2006. It lies at the extreme northeast corner of Aberdeenshire, around north of Aberdeen, and north of Peterhead...

, Turriff

Turriff

Turriff is a town and civil parish in Aberdeenshire in Scotland. It is approximately above sea level, and has a population of 5,708.Turriff is known locally as Turra in the Doric dialect of Scots...

and Rosehearty

Rosehearty

Rosehearty , Rizarty in the local dialect, is located on the Moray Firth coast, four miles west of the town Fraserburgh, in the historical county of Aberdeenshire in Scotland....

. He was appointed an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1950, a KBE

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

in 1953.

Boothby was raised to the peerage as a life peer

Life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the Peerage whose titles cannot be inherited. Nowadays life peerages, always of baronial rank, are created under the Life Peerages Act 1958 and entitle the holders to seats in the House of Lords, presuming they meet qualifications such as...

with the title Baron Boothby, of Buchan

Buchan

Buchan is one of the six committee areas and administrative areas of Aberdeenshire Council, Scotland. These areas were created by the council in 1996, when the Aberdeenshire unitary council area was created under the Local Government etc Act 1994...

and Rattray Head

Rattray Head

Rattray Head is a headland in Buchan, Aberdeenshire, on the north east coast Scotland. To north lies Strathbeg Bay and Rattray Bay is to its south...

in the County of Aberdeen

Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire is one of the 32 unitary council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area.The present day Aberdeenshire council area does not include the City of Aberdeen, now a separate council area, from which its name derives. Together, the modern council area and the city formed historic...

, on 22 August 1958.

There is a blue plaque

Blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person or event, serving as a historical marker....

on his house in Eaton Square

Eaton Square

Eaton Square is a residential garden square in London's Belgravia district. It is one of the three garden squares built by the Grosvenor family when they developed the main part of Belgravia in the 19th century, and is named after Eaton Hall, the Grosvenor country house in Cheshire...

, London.

Personal life

Boothby had a colourful, if reasonably discreet, private life, mainly because the press refused to print what they knew of him, or were prevented from doing so. Woodrow WyattWoodrow Wyatt

Woodrow Lyle Wyatt, Baron Wyatt of Weeford , was a British politician, published author, journalist and broadcaster, close to the Queen Mother, Margaret Thatcher and Rupert Murdoch...

– whose reliability has been questioned – claimed after the death of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon was the queen consort of King George VI from 1936 until her husband's death in 1952, after which she was known as Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, to avoid confusion with her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II...

that she had confided to him in a 1991 interview that "The press knew all about it", referring to Boothby's affairs, and that she described him as "a bounder but not a cad".

He was married twice: in 1935 to Diana Cavendish (marriage dissolved in 1937) and in 1967 to Wanda Sanna, a Sardinian woman, 33 years his junior. The writer and broadcaster Sir Ludovic Kennedy

Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy was a British journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author best known for re-examining cases such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and the murder convictions of Timothy Evans and Derek Bentley, and for his role in the abolition of the death penalty in the United...

has asserted that Boothby fathered at least three children by the wives of other men (two by one woman, one by another)."

From 1930 he had a long affair with Dorothy Macmillan, wife of the Conservative politician Harold Macmillan

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC was Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963....

(who would serve as prime minister from 1957 until 1963). He was rumoured to be father of the youngest Macmillan daughter, Sarah, though Harold Macmillan's most recent biographer D. R. Thorpe discounts Boothby's paternity. This connection to Macmillan, via his wife, has been seen as one of the reasons why the police didn't investigate the death of Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire

Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire

Edward William Spencer Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire, KG, MBE, TD , known as Marquess of Hartington , was the head of the Devonshire branch of the Cavendish family...

, who died in the presence of suspected serial killer

Serial killer

A serial killer, as typically defined, is an individual who has murdered three or more people over a period of more than a month, with down time between the murders, and whose motivation for killing is usually based on psychological gratification...

Dr John Bodkin Adams

John Bodkin Adams

John Bodkin Adams was an Irish-born British general practitioner, convicted fraudster and suspected serial killer. Between the years 1946 and 1956, more than 160 of his patients died in suspicious circumstances. Of these, 132 left him money or items in their will. He was tried and acquitted for...

. The duke was Lady Dorothy's brother, and it is thought the police were wary of drawing press attention to her while she was being unfaithful.

Sexuality and the Kray twins

Boothby was a promiscuous bisexual, in a time when male homosexual activity was a criminal offence. While an undergraduate at Magdalen College, OxfordMagdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2006 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £153 million. Magdalen is currently top of the Norrington Table after over half of its 2010 finalists received first-class degrees, a record...

, Boothby earned the nickname "the Palladium

London Palladium

The London Palladium is a 2,286 seat West End theatre located off Oxford Street in the City of Westminster. From the roster of stars who have played there and many televised performances, it is arguably the most famous theatre in London and the United Kingdom, especially for musical variety...

", because "he was twice nightly". He later spoke about the role of a speculated homosexual relationship in the drowning of his friend Michael Llewelyn Davies (one of the models for Peter Pan

Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a character created by Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie . A mischievous boy who can fly and magically refuses to grow up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending childhood adventuring on the small island of Neverland as the leader of his gang the Lost Boys, interacting with...

) and fellow Oxonian Rupert Buxton. He did not start to have physical relationships with women until the age of 25. From 1954 he campaigned publicly for homosexual law reform.

In 1963 Boothby began an illicit affair with East End cat burglar Leslie Holt (d. 1979), a younger man he met at a gambling club. Holt introduced him to the gangster Ronald Kray, the younger Kray twin

Kray twins

Reginald "Reggie" Kray and his twin brother Ronald "Ronnie" Kray were the foremost perpetrators of organised crime in London's East End during the 1950s and 1960s...

, who supplied Boothby with young men and arranged orgies in Cedra Court, receiving personal favours from Boothby in return. When Boothby's underworld associations came to the attention of the Sunday Express, the Conservative

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

-supporting paper opted not to publish the damaging story. The matter was eventually reported in 1964 in the Labour-supporting Sunday Mirror

Sunday Mirror

The Sunday Mirror is the Sunday sister paper of the Daily Mirror. It began life in 1915 as the Sunday Pictorial and was renamed the Sunday Mirror in 1963. Trinity Mirror also owns The People...

tabloid, and the parties subsequently named by the German magazine Stern

Stern (magazine)

Stern is a weekly news magazine published in Germany. It was founded in 1948 by Henri Nannen, and is currently published by Gruner + Jahr, a subsidiary of Bertelsmann. In the first quarter of 2006, its print run was 1.019 million copies and it reached 7.84 million readers according to...

.

Boothby denied the story and threatened to sue the Mirror, and because his close homosexual friend, Tom Driberg

Tom Driberg, Baron Bradwell

Thomas Edward Neil Driberg, Baron Bradwell , generally known as Tom Driberg, was a British journalist, politician and High Anglican churchman who served as a Member of Parliament from 1942 to 1955 and from 1959 to 1974...

, a senior Labour

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

MP, was also involved in the criminal ring, neither of the major political parties had an interest in publicity, and the paper's owner, Cecil King

Cecil Harmsworth King

Cecil Harmsworth King was owner of Mirror Group Newspapers, and later a director at the Bank of England .He came on his father's side from a Protestant Irish family, and was brought up in Ireland...

, came under pressure from the Labour leadership to drop the matter, to protect Driberg. The Mirror backed down, sacked its editor, apologised, and paid Boothby £40,000 in an out-of-court settlement. Consequently other newspapers became less willing to cover the Krays' criminal activities, which continued unchecked for three more years. The police investigation received no support from Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

, while Boothby embarrassed his fellow peers by campaigning on behalf of the Krays in the Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

, until their increasing violence made association impossible. It has been claimed that journalists who investigated Boothby were subjected to legal threats and break-ins, and that much of this suppression was directed by Arnold Goodman

Arnold Goodman, Baron Goodman

Arnold Abraham Goodman, Baron Goodman, CH, QC, was a British lawyer and political advisor.-Life:Lord Goodman was educated at University College London and Downing College, Cambridge. He became a leading London lawyer as Senior Partner in the law firm Goodman, Derrick & Co...

.

Death

After his death in WestminsterCity of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a London borough occupying much of the central area of London, England, including most of the West End. It is located to the west of and adjoining the ancient City of London, directly to the east of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and its southern boundary...

aged 86, Boothby's ashes were scattered at Rattray Head

Rattray Head

Rattray Head is a headland in Buchan, Aberdeenshire, on the north east coast Scotland. To north lies Strathbeg Bay and Rattray Bay is to its south...

near Crimond

Crimond

Crimond is a village in the northeast of Scotland, located nine miles northwest of the port of Peterhead and just over two miles from the coast.- Local area :...

, Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire is one of the 32 unitary council areas in Scotland and a lieutenancy area.The present day Aberdeenshire council area does not include the City of Aberdeen, now a separate council area, from which its name derives. Together, the modern council area and the city formed historic...

.

Publications

- The New Economy, 1943;

- I Fight to Live, 1947;

- My Yesterday, Your Tomorrow, 1962;

- Boothby: recollections of a rebel, 1978.