Pontiac's Rebellion

Encyclopedia

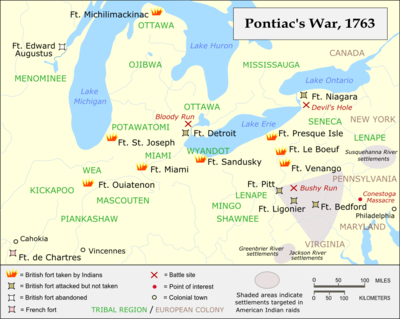

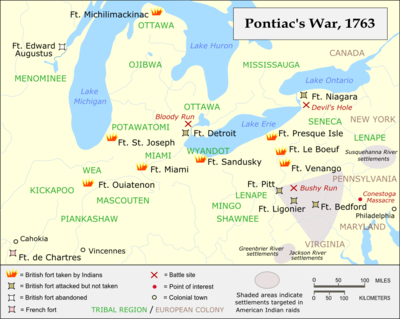

Pontiac's War, Pontiac's Conspiracy, or Pontiac's Rebellion was a war that was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of elements of Native American tribes primarily from the Great Lakes region

, the Illinois Country

, and Ohio Country

who were dissatisfied with British

postwar policies in the Great Lakes region after the British victory in the French and Indian War

(1754–1763). Warriors from numerous tribes joined the uprising in an effort to drive British soldiers and settlers out of the region. The war is named after the Ottawa

leader Pontiac

, the most prominent of many native leaders in the conflict.

The war began in May 1763 when Native Americans, offended by the policies of British General Jeffrey Amherst, attacked a number of British forts and settlements. Eight forts were destroyed, and hundreds of colonists were killed or captured, with many more fleeing the region. Hostilities came to an end after British Army

expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations over the next two years. Native Americans were unable to drive away the British, but the uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

Warfare on the North American frontier was brutal, and the killing of prisoners, the targeting of civilians, and other atrocities were widespread. In what is now perhaps the best-known incident of the war, British officers at Fort Pitt

attempted to infect the besieging

Native Americans with smallpox

using blankets that had been exposed to the virus. The ruthlessness and treachery of the conflict was a reflection of a growing divide between the separate populations of the British colonists and Native Americans. The British government sought to prevent further violence between the two by issuing the Royal Proclamation of 1763

, which created a boundary between colonists and Native Americans. This proved unpopular with British colonists, and may have been one of the early contributing factors to the American Revolution

.

, an influential Seneca

/Mingo

leader. The war became widely known as "Pontiac's Conspiracy" after the publication in 1851 of Francis Parkman

's The Conspiracy of Pontiac. Parkman's influential book, the definitive account of the war for nearly a century, is still in print.

In the 20th century, some historians argued that Parkman exaggerated the extent of Pontiac's influence in the conflict and that it was therefore misleading to name the war after Pontiac. For example, in 1988 Francis Jennings

wrote: "In Francis Parkman's murky mind the backwoods plots emanated from one savage genius, the Ottawa chief Pontiac, and thus they became 'The Conspiracy of Pontiac,' but Pontiac was only a local Ottawa war chief in a 'resistance' involving many tribes." Alternate titles for the war have been proposed, but historians generally continue to refer to the war by the familiar names, with "Pontiac's War" probably the most commonly used. "Pontiac's Conspiracy" is now infrequently used by scholars.

and Great Britain

participated in a series of wars in Europe

that also involved the French and Indian Wars

in North America. The largest of these wars was the worldwide Seven Years' War

, in which France lost New France

in North America to Great Britain. Most fighting in the North American theater

of the war, generally called the French and Indian War

in the United States, came to an end after British General Jeffrey Amherst captured French Montréal

in 1760.

British troops proceeded to occupy the various forts in the Ohio Country

and Great Lakes region

previously garrisoned by the French. Even before the war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763)

, the British Crown began to implement changes in order to administer its vastly expanded North American territory. While the French had long cultivated alliances among certain of the Native Americans, the British post-war approach was essentially to treat the Native Americans as a conquered people. Before long, Native Americans who had been allies of the defeated French found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with the British occupation and the new policies imposed by the victors.

s. At this time and place, a "tribe" was a linguistic or ethnic group rather than a political unit. No chief spoke for an entire tribe, and no tribe acted in unison. For example, Ottawas

did not go to war as a tribe: some Ottawa leaders chose to do so, while other Ottawa leaders denounced the war and stayed clear of the conflict. The tribes of the pays d'en haut consisted of three basic groups.

The first group was the tribes of the Great Lakes region: Ottawas, Ojibwa

s, Potawatomi

s, and Hurons. They had long been allied with French habitants

, with whom they lived, traded, and intermarried. Great Lakes Native Americans were alarmed to learn that they were under British sovereignty after the French loss of North America. When a British garrison took possession of Fort Detroit

from the French in 1760, local Native Americans cautioned them that "this country was given by God to the Indians."

The second group was the tribes of the eastern Illinois Country

The second group was the tribes of the eastern Illinois Country

, which included Miamis

, Wea

s, Kickapoos, Mascouten

s, and Piankashaws. Like the Great Lakes tribes, these people had a long history of close relations with the French. Throughout the war, the British were unable to project military power

into the Illinois Country, which was on the remote western edge of the conflict, and so the Illinois tribes were the last to come to terms with the British.

The third group was the tribes of the Ohio Country: Delawares (Lenape)

, Shawnee

s, Wyandots, and Mingo

s. These people had migrated to the Ohio valley earlier in the century in order to escape British, French, and Iroquois domination elsewhere. Unlike the Great Lakes and Illinois Country tribes, Ohio Native Americans had no great attachment to the French regime, and had fought alongside the French in the previous war only as a means of driving away the British. They made a separate peace with the British with the understanding that the British Army would withdraw from the Ohio Country. But after the departure of the French, the British strengthened their forts in the region rather than abandoning them, and so the Ohioans went to war in 1763 in another attempt to drive out the British.

Outside the pays d'en haut, the influential Iroquois Confederacy

mostly did not participate in Pontiac's War because of their alliance with the British, known as the Covenant Chain

. However, the westernmost Iroquois nation, the Seneca tribe, had become disaffected with the alliance. As early as 1761, Senecas began to send out war messages to the Great Lakes and Ohio Country tribes, urging them to unite in an attempt to drive out the British. When the war finally came in 1763, many Senecas were quick to take action.

General Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America

General Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America

, was in overall charge of administering policy towards Native Americans, which involved both military matters and regulation of the fur trade

. Amherst believed that with France out of the picture, the Native Americans would have no other choice than to accept British rule. He also believed that they were incapable of offering any serious resistance to the British Army; therefore, of the 8,000 troops under his command in North America, only about 500 were stationed in the region where the war erupted. Amherst and officers such as Major Henry Gladwin

, commander at Fort Detroit

, made little effort to conceal their contempt for the Native Americans. Native Americans involved in the uprising frequently complained that the British treated them no better than slaves or dogs.

Additional Native resentment resulted from Amherst's decision in February 1761 to cut back on the gifts given to the Native Americans. Gift giving had been an integral part of the relationship between the French and the tribes of the pays d'en haut. Following a Native American custom that carried important symbolic meaning, the French gave presents (such as guns, knives, tobacco, and clothing) to village chiefs, who in turn redistributed these gifts to their people. By this process, the village chiefs gained stature among their people, and were thus able to maintain the alliance with the French. Amherst, however, considered this process to be a form of bribery that was no longer necessary, especially since he was under pressure to cut expenses after the war with France. Many Native Americans regarded this change in policy as an insult and an indication that the British looked upon them as conquered people rather than as allies.

Amherst also began to restrict the amount of ammunition and gunpowder that traders could sell to Native Americans. While the French had always made these supplies available, Amherst did not trust the Native Americans, particularly after the "Cherokee Rebellion"

of 1761, in which Cherokee

warriors took up arms against their former British allies. The Cherokee war effort had collapsed because of a shortage of gunpowder, and so Amherst hoped that future uprisings could be prevented by limiting the distribution of gunpowder. This created resentment and hardship because gunpowder and ammunition were wanted by native men because it made providing food for their families and skins for the fur trade much easier. Many Native Americans began to believe that the British were disarming them as a prelude to making war upon them. Sir William Johnson

, the Superintendent of the Indian Department, tried to warn Amherst of the dangers of cutting back on presents and gunpowder, to no avail.

had been displaced by British colonists in the east, and this motivated their involvement in the war. On the other hand, Native Americans in the Great Lakes region and the Illinois Country

had not been greatly affected by white settlement, although they were aware of the experiences of tribes in the east. Historian Gregory Dowd argues that most Native Americans involved in Pontiac's Rebellion were not immediately threatened with displacement by white settlers, and that historians have therefore overemphasized British colonial expansion as a cause of the war. Dowd believes that the presence, attitude, and policies of the British Army, which the Native Americans found threatening and insulting, were more important factors.

Also contributing to the outbreak of war was a religious awakening which swept through Native settlements in the early 1760s. The movement was fed by discontent with the British as well as food shortages and epidemic disease. The most influential individual in this phenomenon was Neolin

, known as the "Delaware Prophet", who called upon Native Americans to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the whites. Merging elements

from Christianity

into traditional religious beliefs, Neolin told listeners that the Master of Life

was displeased with the Native Americans for taking up the bad habits of the white men, and that the British posed a threat to their very existence. "If you suffer the English among you," said Neolin, "you are dead men. Sickness, smallpox, and their poison [alcohol] will destroy you entirely." It was a powerful message for a people whose world was being changed by forces that seemed beyond their control.

) which called for the tribes to form a confederacy and drive away the British. The Mingos, led by Guyasuta and Tahaiadoris, were concerned about being surrounded by British forts. Similar war belts originated from Detroit and the Illinois Country. The Native Americans were not unified, however, and in June 1761, Native Americans at Detroit informed the British commander of the Seneca plot. After William Johnson held a large council with the tribes at Detroit in September 1761 a tenuous peace was maintained, but war belts continued to circulate. Violence finally erupted after the Native Americans learned in early 1763 of the imminent French cession of the pays d'en haut to the British.

The war began at Fort Detroit under the leadership of Pontiac, and quickly spread throughout the region. Eight British forts were taken; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac portrayed these attacks as a coordinated operation planned by Pontiac. Parkman's interpretation remains well known, but other historians have since argued that there is no clear evidence that the attacks were part of a master plan or overall "conspiracy". The prevailing view among scholars today is that, rather than being planned in advance, the uprising spread as word of Pontiac's actions at Detroit traveled throughout the pays d'en haut, inspiring already discontented Native Americans to join the revolt. The attacks on British forts were not simultaneous: most Ohio Native Americans did not enter the war until nearly a month after the beginning of Pontiac's siege at Detroit.

Parkman also believed that Pontiac's War had been secretly instigated by French colonists

who were stirring up the Native Americans in order to make trouble for the British. This belief was widely held by British officials at the time, but subsequent historians have found no evidence of official French involvement in the uprising. (The rumor of French instigation arose in part because French war belts from the Seven Years' War were still in circulation in some Native villages.) Rather than the French stirring up the Native Americans, some historians now argue that the Native Americans were trying to stir up the French. Pontiac and other native leaders frequently spoke of the imminent return of French power and the revival of the Franco-Native alliance; Pontiac even flew a French flag in his village. All of this was apparently intended to inspire the French to rejoin the struggle against the British. Although some French colonists and traders supported the uprising, the war was initiated and conducted by Native Americans who had Native—not French—objectives.

Middleton (2007) argues that Pontiac's vision, courage, persistence, and organizational abilities allowed him to activate a remarkable coalition of Indian nations prepared to fight successfully against the British. Though the idea to liberate Native Americans west of the Alleghany Mountains did not originate with him but with two Seneca leaders, by February 1763 Pontiac appeared to embrace the idea. At an emergency council meeting, Pontiac clarified his military support of the broad Seneca plan and worked to galvanize other nations into the military operation that he helped lead, in direct contradiction to traditional Indian leadership and tribal structure.

. Using the teachings of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwa

s, Potawatomi

s, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit

. On May 1, Pontiac visited the fort with 50 Ottawas in order to assess the strength of the garrison. According to a French chronicler, in a second council Pontiac proclaimed:

Hoping to take the stronghold by surprise, on May 7 Pontiac entered Fort Detroit with about 300 men carrying concealed weapons. The British had learned of Pontiac's plan, however, and were armed and ready. His tactic foiled, Pontiac withdrew after a brief council and, two days later, laid siege to the fort. Pontiac and his allies killed all of the British soldiers and settlers they could find outside of the fort, including women and children. One of the soldiers was ritually cannibalized

, as was the custom in some Great Lakes Native cultures. The violence was directed at the British; French colonists were generally left alone. Eventually more than 900 warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege. Meanwhile, on 28 May a British supply column from Fort Niagara

led by Lieutenant

Abraham Cuyler was ambushed and defeated at Point Pelee

.

After receiving reinforcements, the British attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiac's encampment. But Pontiac was ready and waiting, and defeated them at the Battle of Bloody Run

After receiving reinforcements, the British attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiac's encampment. But Pontiac was ready and waiting, and defeated them at the Battle of Bloody Run

on July 31, 1763. Nevertheless, the situation at Fort Detroit remained a stalemate, and Pontiac's influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Native Americans began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. On October 31, 1763, finally convinced that the French in Illinois would not come to his aid at Detroit, Pontiac lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River

, where he continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.

, a small blockhouse

on the shore of Lake Erie

. It had been built in 1761 by order of General Amherst, despite the objections of local Wyandots, who in 1762 warned the commander that they would soon burn it down. On May 16, 1763, a group of Wyandots gained entry under the pretense of holding a council, the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit nine days earlier. They seized the commander and killed the other 15 soldiers, as well as British traders at the fort. These were among the first of about 100 traders who were killed in the early stages of the war. The dead were ritually scalped

and the fort—as the Wyandots had warned a year earlier—was burned to the ground.

Fort St. Joseph

(the site of present-day Niles

, Michigan

) was captured on May 25, 1763, by the same method as at Sandusky. Potawatomis seized the commander and killed most of the 15-man garrison outright. Fort Miami

(on the site of present Fort Wayne

, Indiana

) was the third fort to fall. On May 27, 1763, the commander was lured out of the fort by his Native mistress and shot dead by Miami Native Americans. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.

In the Illinois Country, Weas, Kickapoos, and Mascoutens took Fort Ouiatenon

(about 5 miles (8 km) southwest of present Lafayette

, Indiana

) on June 1, 1763. They lured soldiers outside for a council, and took the 20-man garrison captive without bloodshed. The Native Americans around Fort Ouiatenon had good relations with the British garrison, but emissaries from Pontiac at Detroit had convinced them to strike. The warriors apologized to the commander for taking the fort, saying that "they were obliged to do it by the other Nations." In contrast with other forts, the Natives did not kill the British captives at Ouiatenon.

The fifth fort to fall, Fort Michilimackinac

(present Mackinaw City

, Michigan

), was the largest fort taken by surprise. On June 2, 1763, local Ojibwas staged a game of stickball (a forerunner of lacrosse

) with visiting Sauks. The soldiers watched the game, as they had done on previous occasions. The ball was hit through the open gate of the fort; the teams rushed in and were given weapons which Native women had smuggled into the fort. The warriors killed about 15 of the 35-man garrison in the struggle; later they killed five more in ritual torture.

Three forts in the Ohio Country were taken in a second wave of attacks in mid-June. Iroquois

Seneca

s took Fort Venango

(near the site of the present Franklin, Pennsylvania

) around June 16, 1763. They killed the entire 12-man garrison outright, keeping the commander alive to write down the grievances of the Senecas. After that, they ritually burned him at the stake. Possibly the same Seneca warriors attacked Fort Le Boeuf

(on the site of Waterford

, Pennsylvania

) on June 18, but most of the 12-man garrison escaped to Fort Pitt.

On June 19, 1763, about 250 Ottawa, Ojibwa, Wyandot, and Seneca warriors surrounded Fort Presque Isle

(on the site of Erie

, Pennsylvania

), the eighth and final fort to fall. After holding out for two days, the garrison of about 30 to 60 men surrendered, on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt. The warriors killed most of the soldiers after they came out of the fort.

is among us." Fort Pitt was attacked on June 22, 1763, primarily by Delawares. Too strong to be taken by force, the fort was kept under siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee

war parties raided deep into Pennsylvania, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of settlers in scattered farms. Two smaller strongholds that linked Fort Pitt to the east, Fort Bedford

and Fort Ligonier

, were sporadically fired upon throughout the conflict, but were never taken.

Before the war, Amherst had dismissed the possibility that the Native Americans would offer any effective resistance to British rule, but that summer he found the military situation becoming increasingly grim. He ordered subordinates to "immediately ... put to death" captured enemy Native American warriors. To Colonel Henry Bouquet

at Lancaster

, Pennsylvania

, who was preparing to lead an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt, Amherst wrote on about June 29, 1763: "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them."

Bouquet agreed, replying to Amherst on July 13: "I will try to inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself." Amherst responded on July 16: "You will do well to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race."

Officers at the besieged Fort Pitt had already attempted to do what Amherst and Bouquet were discussing, apparently on their own initiative. During a parley at Fort Pitt on June 24, 1763, Ecuyer gave Delaware representatives two blankets and a handkerchief that had been exposed to smallpox, hoping to spread the disease to the Native Americans in order to end the siege. William Trent, the militia commander, left records that showed the purpose of giving the blankets was "to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians."

It is uncertain whether this fully documented attempt to spread smallpox to the Native Americans was successful. Because many Native Americans died from smallpox during Pontiac's Rebellion, historian Francis Jennings concluded that the attempt was "unquestionably effective". But, some subsequent scholars have raised doubts about whether the smallpox outbreak can be traced to blankets from Fort Pitt with certainty.

According to an eyewitness report, smallpox was spreading among the Ohio Native Americans before the blanket incident. Because smallpox was already in the area, it may have reached Native villages through a number of sources. Eyewitnesses reported that Native warriors contracted the disease after attacking infected white settlements, and spread the disease upon their return home. Historian Michael McConnell argued that even if the Fort Pitt attempt was successful, Native Americans were familiar with the disease and adept at isolating the infected. For these reasons, McConnell concluded that "British efforts to use pestilence as a weapon may not have been either necessary or particularly effective." According to historian David Dixon, the Native Americans outside Fort Pitt were apparently unaffected by any outbreak of disease. Dixon argued that "the Indians may well have received the dreaded disease from a number of sources, but infected blankets from Fort Pitt was not one of them."

. Although his force suffered heavy casualties, Bouquet fought off the attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20, bringing the siege to an end. His victory at Bushy Run was celebrated in the British colonies—church bells rang through the night in Philadelphia—and praised by King George

.

This victory was soon followed by a costly defeat. Fort Niagara

, one of the most important western forts, was not assaulted, but on September 14, 1763, at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls

portage. Two companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. More than 70 soldiers and teamsters were killed in these actions, which Anglo-Americans called the "Devil's Hole Massacre", the deadliest engagement for British soldiers during the war.

The violence and terror of Pontiac's War convinced many western Pennsylvanians that their government was not doing enough to protect them. This discontent was manifested most seriously in an uprising led by a vigilante

The violence and terror of Pontiac's War convinced many western Pennsylvanians that their government was not doing enough to protect them. This discontent was manifested most seriously in an uprising led by a vigilante

group that came to be known as the Paxton Boys

, so-called because they were primarily from the area around the Pennsylvania village of Paxton (or Paxtang

). The Paxtonians turned their anger towards Native Americans—many of them Christians—who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements. Prompted by rumors that a Native war party had been seen at the Native village of Conestoga, on December 14, 1763, a group of more than 50 Paxton Boys marched on the village and murdered the six Susquehannock

s they found there. Pennsylvania officials placed the remaining 14 Susquehannocks in protective custody in Lancaster

, but on December 27 the Paxton Boys broke into the jail and slaughtered them. Governor John Penn

issued bounties for the arrest of the murderers, but no one came forward to identify them.

The Paxton Boys then set their sights on other Native Americans living within eastern Pennsylvania, many of whom fled to Philadelphia for protection. Several hundred Paxtonians marched on Philadelphia in January 1764, where the presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia

prevented them from doing more violence. Benjamin Franklin

, who had helped organize the local militia, negotiated with the Paxton leaders and brought an end to the immediate crisis. Franklin published a scathing indictment of the Paxton Boys. "If an Indian injures me," he asked, "does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?" One leader of the Paxton Boys was Lazarus Stewart

who would be killed in the Wyoming Massacre of 1778.

, 15 colonists working in a field near Fort Cumberland

were killed. On June 14, about 13 settlers near Fort Loudoun

in Pennsylvania were killed and their homes burned. The most notorious raid

occurred on July 26, when four Delaware warriors killed and scalped a school teacher and ten children in what is now Franklin County

, Pennsylvania

. Incidents such as these prompted the Pennsylvania Assembly, with the approval of Governor Penn, to reintroduce the scalp bounties offered during the French and Indian War, which paid money for every Native killed above the age of ten, including women.

General Amherst, held responsible for the uprising by the Board of Trade

, was recalled to London in August 1763 and replaced by Major General Thomas Gage

. In 1764, Gage sent two expeditions into the west to crush the rebellion, rescue British prisoners, and arrest the Native Americans responsible for the war. According to historian Fred Anderson

, Gage's campaign, which had been designed by Amherst, prolonged the war for more than a year because it focused on punishing the Native Americans rather than ending the war. Gage's one significant departure from Amherst's plan was to allow William Johnson to conduct a peace treaty at Niagara, giving those Native Americans who were ready to "bury the hatchet" a chance to do so.

with about 2,000 Native Americans in attendance, primarily Iroquois. Although most Iroquois had stayed out of the war, Senecas from the Genesee River

valley had taken up arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the Covenant Chain

alliance. As restitution for the Devil's Hole ambush, the Senecas were compelled to cede the strategically important Niagara portage to the British. Johnson even convinced the Iroquois to send a war party against the Ohio Native Americans. This Iroquois expedition captured a number of Delawares and destroyed abandoned Delaware and Shawnee towns in the Susquehanna Valley

, but otherwise the Iroquois did not contribute to the war effort as much as Johnson had desired.

, was to travel by boat across Lake Erie and reinforce Detroit. Bradstreet was to subdue the Native Americans around Detroit before marching south into the Ohio Country. The second expedition, commanded by Colonel Bouquet, was to march west from Fort Pitt and form a second front in the Ohio Country.

Bradstreet set out from Fort Schlosser

in early August 1764 with about 1,200 soldiers and a large contingent of Native allies enlisted by Sir William Johnson. Bradstreet felt that he did not have enough troops to subdue enemy Native Americans by force, and so when strong winds on Lake Erie forced him to stop at Presque Isle

on August 12, he decided to negotiate a treaty with a delegation of Ohio Native Americans led by Guyasuta. Bradstreet exceeded his authority by conducting a peace treaty rather than a simple truce, and by agreeing to halt Bouquet's expedition, which had not yet left Fort Pitt. Gage, Johnson, and Bouquet were outraged when they learned what Bradstreet had done. Gage rejected the treaty, believing that Bradstreet had been duped into abandoning his offensive in the Ohio Country. Gage may have been correct: the Ohio Native Americans did not return prisoners as promised in a second meeting with Bradstreet in September, and some Shawnees were trying to enlist French aid in order to continue the war.

Bradstreet continued westward, as yet unaware that his unauthorized diplomacy was angering his superiors. He reached Fort Detroit on August 26, where he negotiated another treaty. In an attempt to discredit Pontiac, who was not present, Bradstreet chopped up a peace belt the Ottawa leader had sent to the meeting. According to historian Richard White

, "such an act, roughly equivalent to a European ambassador's urinating on a proposed treaty, had shocked and offended the gathered Indians." Bradstreet also claimed that the Native Americans had accepted British sovereignty as a result of his negotiations, but Johnson believed that this had not been fully explained to the Native Americans and that further councils would be needed. Although Bradstreet had successfully reinforced and reoccupied British forts in the region, his diplomacy proved to be controversial and inconclusive.

Colonel Bouquet, delayed in Pennsylvania while mustering the militia, finally set out from Fort Pitt on October 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. He marched to the Muskingum River

Colonel Bouquet, delayed in Pennsylvania while mustering the militia, finally set out from Fort Pitt on October 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. He marched to the Muskingum River

in the Ohio Country, within striking distance of a number of native villages. Now that treaties had been negotiated at Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit, the Ohio Native Americans were isolated and, with some exceptions, ready to make peace. In a council which began on 17 October, Bouquet demanded that the Ohio Native Americans return all captives, including those not yet returned from the French and Indian War. Guyasuta and other leaders reluctantly handed over more than 200 captives, many of whom had been adopted into Native families. Because not all of the captives were present, the Native Americans were compelled to surrender hostages as a guarantee that the other captives would be returned. The Ohio Native Americans agreed to attend a more formal peace conference with William Johnson, which was finalized in July 1765.

from the French. A Shawnee war chief named Charlot Kaské

emerged as the most strident anti-British leader in the region, temporarily surpassing Pontiac in influence. Kaské traveled as far south as New Orleans in an effort to enlist French aid against the British.

In 1765, the British decided that the occupation of the Illinois Country could only be accomplished by diplomatic means. British officials focused on Pontiac, who had become less militant after hearing of Bouquet's truce with the Ohio country Native Americans. Johnson's deputy, George Croghan

, traveled to the Illinois country in the summer of 1765, and although he was injured along the way in an attack by Kickapoos and Mascoutens, he managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac. While Charlot Kaské wanted to burn Croghan at the stake, Pontiac urged moderation and agreed to travel to New York, where he made a formal treaty with William Johnson at Fort Ontario

on July 25, 1766. It was hardly a surrender: no lands were ceded, no prisoners returned, and no hostages were taken. Rather than accept British sovereignty, Kaské left British territory by crossing the Mississippi River

with other French and Native refugees.

Pontiac's War has traditionally been portrayed as a defeat for the Native Americans, but scholars now usually view it as a military stalemate: while the Native Americans had failed to drive away the British, the British were unable to conquer the Native Americans. Negotiation and accommodation, rather than success on the battlefield, ultimately brought an end to the war. The Native Americans had in fact won a victory of sorts by compelling the British government to abandon Amherst's policies and instead create a relationship with the Native Americans modeled on the Franco-Native alliance.

Relations between British colonists and Native Americans, which had been severely strained during the French and Indian War, reached a new low during Pontiac's Rebellion. According to historian David Dixon, "Pontiac's War was unprecedented for its awful violence, as both sides seemed intoxicated with genocidal

fanaticism." Historian Daniel Richter characterizes the Native attempt to drive out the British, and the effort of the Paxton Boys to eliminate Native Americans from their midst, as parallel examples of ethnic cleansing

. People on both sides of the conflict had come to the conclusion that colonists and Native Americans were inherently different and could not live with each other. According to Richter, the war saw the emergence of "the novel idea that all Native people were 'Indians,' that all Euro-Americans were 'Whites,' and that all on one side must unite to destroy the other."

The British government also came to the conclusion that colonists and Native Americans must be kept apart. On October 7, 1763, the Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763

, an effort to reorganize British North America

after the Treaty of Paris

. The Proclamation, already in the works when Pontiac's War erupted, was hurriedly issued after news of the uprising reached London. Officials drew a boundary line between the British colonies along the seaboard and Native American lands west of the Appalachian Mountains

, creating a vast 'Indian Reserve'

that stretched from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River

and from Florida

to Quebec

. By forbidding colonists from trespassing on Native lands, the British government hoped to avoid more conflicts like Pontiac's Rebellion. "The Royal Proclamation," writes historian Colin Calloway, "reflected the notion that segregation not interaction should characterize Indian-white relations."

The effects of Pontiac's War were long-lasting. Because the Proclamation officially recognized that indigenous people had certain rights to the lands they occupied, it has been called the Native Americans' "Bill of Rights", and still informs the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations

. For British colonists and land speculators, however, the Proclamation seemed to deny them the fruits of victory—western lands—that had been won in the war with France. The resentment which this created undermined colonial attachment to the Empire, contributing to the coming of the American Revolution

. According to Colin Calloway, "Pontiac's Revolt was not the last American war for independence—American colonists launched a rather more successful effort a dozen years later, prompted in part by the measures the British government took to try to prevent another war like Pontiac's."

For Native Americans, Pontiac's War demonstrated the possibilities of pan-tribal cooperation in resisting Anglo-American colonial expansion. Although the conflict divided tribes and villages, the war also saw the first extensive multi-tribal resistance to European colonization

in North America, and was the first war between Europeans and Native North Americans that did not end in complete defeat for the Native Americans. The Proclamation of 1763 ultimately did not prevent British colonists and land speculators from expanding westward, and so Native Americans found it necessary to form new resistance movements. Beginning with conferences hosted by Shawnees in 1767, in the following decades leaders such as Joseph Brant

, Alexander McGillivray

, Blue Jacket

, and Tecumseh

would attempt to forge confederacies that would revive the resistance efforts of Pontiac's War.

Great Lakes region (North America)

The Great Lakes region of North America, occasionally known as the Third Coast or the Fresh Coast , includes the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as well as the Canadian province of Ontario...

, the Illinois Country

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

, and Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

who were dissatisfied with British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

postwar policies in the Great Lakes region after the British victory in the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

(1754–1763). Warriors from numerous tribes joined the uprising in an effort to drive British soldiers and settlers out of the region. The war is named after the Ottawa

Odawa people

The Odawa or Ottawa, said to mean "traders," are a Native American and First Nations people. They are one of the Anishinaabeg, related to but distinct from the Ojibwe nation. Their original homelands are located on Manitoulin Island, near the northern shores of Lake Huron, on the Bruce Peninsula in...

leader Pontiac

Chief Pontiac

Pontiac or Obwandiyag , was an Ottawa leader who became famous for his role in Pontiac's Rebellion , an American Indian struggle against the British military occupation of the Great Lakes region following the British victory in the French and Indian War. Historians disagree about Pontiac's...

, the most prominent of many native leaders in the conflict.

The war began in May 1763 when Native Americans, offended by the policies of British General Jeffrey Amherst, attacked a number of British forts and settlements. Eight forts were destroyed, and hundreds of colonists were killed or captured, with many more fleeing the region. Hostilities came to an end after British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations over the next two years. Native Americans were unable to drive away the British, but the uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

Warfare on the North American frontier was brutal, and the killing of prisoners, the targeting of civilians, and other atrocities were widespread. In what is now perhaps the best-known incident of the war, British officers at Fort Pitt

Fort Pitt (Pennsylvania)

Fort Pitt was a fort built at the location of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.-French and Indian War:The fort was built from 1759 to 1761 during the French and Indian War , next to the site of former Fort Duquesne, at the confluence the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River...

attempted to infect the besieging

Siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition or assault. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit". Generally speaking, siege warfare is a form of constant, low intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static...

Native Americans with smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

using blankets that had been exposed to the virus. The ruthlessness and treachery of the conflict was a reflection of a growing divide between the separate populations of the British colonists and Native Americans. The British government sought to prevent further violence between the two by issuing the Royal Proclamation of 1763

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued October 7, 1763, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

, which created a boundary between colonists and Native Americans. This proved unpopular with British colonists, and may have been one of the early contributing factors to the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

.

Naming the conflict

The conflict is named after its most famous participant, the Ottawa leader Pontiac; variations include "Pontiac's War", "Pontiac's Rebellion", and "Pontiac's Uprising". An early name for the war was the "Kiyasuta and Pontiac War", "Kiyasuta" being an alternate spelling for GuyasutaGuyasuta

Guyasuta was an important leader of the Seneca people in the second half of the eighteenth century, playing a central role in the diplomacy and warfare of that era...

, an influential Seneca

Seneca nation

The Seneca are a group of indigenous people native to North America. They were the nation located farthest to the west within the Six Nations or Iroquois League in New York before the American Revolution. While exact population figures are unknown, approximately 15,000 to 25,000 Seneca live in...

/Mingo

Mingo

The Mingo are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans made up of peoples who migrated west to the Ohio Country in the mid-eighteenth century. Anglo-Americans called these migrants mingos, a corruption of mingwe, an Eastern Algonquian name for Iroquoian-language groups in general. Mingos have also...

leader. The war became widely known as "Pontiac's Conspiracy" after the publication in 1851 of Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman was an American historian, best known as author of The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life and his monumental seven-volume France and England in North America. These works are still valued as history and especially as literature, although the biases of his...

's The Conspiracy of Pontiac. Parkman's influential book, the definitive account of the war for nearly a century, is still in print.

In the 20th century, some historians argued that Parkman exaggerated the extent of Pontiac's influence in the conflict and that it was therefore misleading to name the war after Pontiac. For example, in 1988 Francis Jennings

Francis Jennings

Francis Jennings was an American historian, best known for his works on the colonial history of the United States.Jennings taught at Cedar Crest College....

wrote: "In Francis Parkman's murky mind the backwoods plots emanated from one savage genius, the Ottawa chief Pontiac, and thus they became 'The Conspiracy of Pontiac,' but Pontiac was only a local Ottawa war chief in a 'resistance' involving many tribes." Alternate titles for the war have been proposed, but historians generally continue to refer to the war by the familiar names, with "Pontiac's War" probably the most commonly used. "Pontiac's Conspiracy" is now infrequently used by scholars.

Origins

In the decades before Pontiac's Rebellion, FranceFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

participated in a series of wars in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

that also involved the French and Indian Wars

French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars is a name used in the United States for a series of conflicts lasting 74 years in North America that represented colonial events related to the European dynastic wars...

in North America. The largest of these wars was the worldwide Seven Years' War

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

, in which France lost New France

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

in North America to Great Britain. Most fighting in the North American theater

Theater (warfare)

In warfare, a theater, is defined as an area or place within which important military events occur or are progressing. The entirety of the air, land, and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations....

of the war, generally called the French and Indian War

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War is the common American name for the war between Great Britain and France in North America from 1754 to 1763. In 1756, the war erupted into the world-wide conflict known as the Seven Years' War and thus came to be regarded as the North American theater of that war...

in the United States, came to an end after British General Jeffrey Amherst captured French Montréal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

in 1760.

British troops proceeded to occupy the various forts in the Ohio Country

Ohio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

and Great Lakes region

Great Lakes region (North America)

The Great Lakes region of North America, occasionally known as the Third Coast or the Fresh Coast , includes the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as well as the Canadian province of Ontario...

previously garrisoned by the French. Even before the war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763)

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, often called the Peace of Paris, or the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. It ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

, the British Crown began to implement changes in order to administer its vastly expanded North American territory. While the French had long cultivated alliances among certain of the Native Americans, the British post-war approach was essentially to treat the Native Americans as a conquered people. Before long, Native Americans who had been allies of the defeated French found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with the British occupation and the new policies imposed by the victors.

Tribes involved

Native Americans involved in Pontiac's Rebellion lived in a vaguely defined region of New France known as the pays d'en haut ("the upper country"), which was claimed by France until the Paris peace treaty of 1763. Native Americans of the pays d'en haut were from many different tribeTribe

A tribe, viewed historically or developmentally, consists of a social group existing before the development of, or outside of, states.Many anthropologists use the term tribal society to refer to societies organized largely on the basis of kinship, especially corporate descent groups .Some theorists...

s. At this time and place, a "tribe" was a linguistic or ethnic group rather than a political unit. No chief spoke for an entire tribe, and no tribe acted in unison. For example, Ottawas

Ottawa (tribe)

The Odawa or Ottawa, said to mean "traders," are a Native American and First Nations people. They are one of the Anishinaabeg, related to but distinct from the Ojibwe nation. Their original homelands are located on Manitoulin Island, near the northern shores of Lake Huron, on the Bruce Peninsula in...

did not go to war as a tribe: some Ottawa leaders chose to do so, while other Ottawa leaders denounced the war and stayed clear of the conflict. The tribes of the pays d'en haut consisted of three basic groups.

The first group was the tribes of the Great Lakes region: Ottawas, Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

s, Potawatomi

Potawatomi

The Potawatomi are a Native American people of the upper Mississippi River region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a member of the Algonquian family. In the Potawatomi language, they generally call themselves Bodéwadmi, a name that means "keepers of the fire" and that was applied...

s, and Hurons. They had long been allied with French habitants

Habitants

Habitants is the name used to refer to both the French settlers and the inhabitants of French origin who farmed the land along the two shores of the St. Lawrence Gulf and River in what is the present-day Province of Quebec in Canada...

, with whom they lived, traded, and intermarried. Great Lakes Native Americans were alarmed to learn that they were under British sovereignty after the French loss of North America. When a British garrison took possession of Fort Detroit

Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Détroit was a fort established by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701. The location of the former fort is now in the city of Detroit in the U.S...

from the French in 1760, local Native Americans cautioned them that "this country was given by God to the Indians."

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

, which included Miamis

Miami tribe

The Miami are a Native American nation originally found in what is now Indiana, southwest Michigan, and western Ohio. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is the only federally recognized tribe of Miami Indians in the United States...

, Wea

Wea

The Wea were a Miami-Illinois-speaking tribe originally located in western Indiana, closely related to the Miami. The name Wea is used today as the a shortened version of their many recorded names...

s, Kickapoos, Mascouten

Mascouten

The Mascouten were a tribe of Algonquian-speaking native Americans who are believed to have dwelt on both sides of the Mississippi River adjacent to the present-day Wisconsin-Illinois border....

s, and Piankashaws. Like the Great Lakes tribes, these people had a long history of close relations with the French. Throughout the war, the British were unable to project military power

Power projection

Power projection is a term used in military and political science to refer to the capacity of a state to conduct expeditionary warfare, i.e. to intimidate other nations and implement policy by means of force, or the threat thereof, in an area distant from its own territory.This ability is a...

into the Illinois Country, which was on the remote western edge of the conflict, and so the Illinois tribes were the last to come to terms with the British.

The third group was the tribes of the Ohio Country: Delawares (Lenape)

Lenape

The Lenape are an Algonquian group of Native Americans of the Northeastern Woodlands. They are also called Delaware Indians. As a result of the American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, today the main groups live in Canada, where they are enrolled in the...

, Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

s, Wyandots, and Mingo

Mingo

The Mingo are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans made up of peoples who migrated west to the Ohio Country in the mid-eighteenth century. Anglo-Americans called these migrants mingos, a corruption of mingwe, an Eastern Algonquian name for Iroquoian-language groups in general. Mingos have also...

s. These people had migrated to the Ohio valley earlier in the century in order to escape British, French, and Iroquois domination elsewhere. Unlike the Great Lakes and Illinois Country tribes, Ohio Native Americans had no great attachment to the French regime, and had fought alongside the French in the previous war only as a means of driving away the British. They made a separate peace with the British with the understanding that the British Army would withdraw from the Ohio Country. But after the departure of the French, the British strengthened their forts in the region rather than abandoning them, and so the Ohioans went to war in 1763 in another attempt to drive out the British.

Outside the pays d'en haut, the influential Iroquois Confederacy

Iroquois

The Iroquois , also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are an association of several tribes of indigenous people of North America...

mostly did not participate in Pontiac's War because of their alliance with the British, known as the Covenant Chain

Covenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties involving the Iroquois Confederacy , the British colonies of North America, and a number of other Indian tribes...

. However, the westernmost Iroquois nation, the Seneca tribe, had become disaffected with the alliance. As early as 1761, Senecas began to send out war messages to the Great Lakes and Ohio Country tribes, urging them to unite in an attempt to drive out the British. When the war finally came in 1763, many Senecas were quick to take action.

Amherst's policies

Commander-in-Chief, North America

The office of Commander-in-Chief, North America was a military position of the British Army. Established in 1755 in the early years of the Seven Years' War, holders of the post were generally responsible for land-based military personnel and activities in and around those parts of North America...

, was in overall charge of administering policy towards Native Americans, which involved both military matters and regulation of the fur trade

Fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of world market for in the early modern period furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most valued...

. Amherst believed that with France out of the picture, the Native Americans would have no other choice than to accept British rule. He also believed that they were incapable of offering any serious resistance to the British Army; therefore, of the 8,000 troops under his command in North America, only about 500 were stationed in the region where the war erupted. Amherst and officers such as Major Henry Gladwin

Henry Gladwin

Henry Gladwin was the British commander at Fort Detroit when it was besieged during Pontiac's Rebellion.British army officer in colonial America...

, commander at Fort Detroit

Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Détroit was a fort established by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701. The location of the former fort is now in the city of Detroit in the U.S...

, made little effort to conceal their contempt for the Native Americans. Native Americans involved in the uprising frequently complained that the British treated them no better than slaves or dogs.

Additional Native resentment resulted from Amherst's decision in February 1761 to cut back on the gifts given to the Native Americans. Gift giving had been an integral part of the relationship between the French and the tribes of the pays d'en haut. Following a Native American custom that carried important symbolic meaning, the French gave presents (such as guns, knives, tobacco, and clothing) to village chiefs, who in turn redistributed these gifts to their people. By this process, the village chiefs gained stature among their people, and were thus able to maintain the alliance with the French. Amherst, however, considered this process to be a form of bribery that was no longer necessary, especially since he was under pressure to cut expenses after the war with France. Many Native Americans regarded this change in policy as an insult and an indication that the British looked upon them as conquered people rather than as allies.

Amherst also began to restrict the amount of ammunition and gunpowder that traders could sell to Native Americans. While the French had always made these supplies available, Amherst did not trust the Native Americans, particularly after the "Cherokee Rebellion"

Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War , also known as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, the Cherokee Rebellion, was a conflict between British forces in North America and Cherokee Indians during the French and Indian War...

of 1761, in which Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

warriors took up arms against their former British allies. The Cherokee war effort had collapsed because of a shortage of gunpowder, and so Amherst hoped that future uprisings could be prevented by limiting the distribution of gunpowder. This created resentment and hardship because gunpowder and ammunition were wanted by native men because it made providing food for their families and skins for the fur trade much easier. Many Native Americans began to believe that the British were disarming them as a prelude to making war upon them. Sir William Johnson

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet was an Anglo-Irish official of the British Empire. As a young man, Johnson came to the Province of New York to manage an estate purchased by his uncle, Admiral Peter Warren, which was located amidst the Mohawk, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois League...

, the Superintendent of the Indian Department, tried to warn Amherst of the dangers of cutting back on presents and gunpowder, to no avail.

Land and religion

Land was also an issue in the coming of the war. While the French colonists—few of whom were farmers—had always been relatively few, there seemed to be no end of settlers in the British colonies. Shawnees and Delawares in the Ohio CountryOhio Country

The Ohio Country was the name used in the 18th century for the regions of North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and in the region of the upper Ohio River south of Lake Erie...

had been displaced by British colonists in the east, and this motivated their involvement in the war. On the other hand, Native Americans in the Great Lakes region and the Illinois Country

Illinois Country

The Illinois Country , also known as Upper Louisiana, was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States that was explored and settled by the French during the 17th and 18th centuries. The terms referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in...

had not been greatly affected by white settlement, although they were aware of the experiences of tribes in the east. Historian Gregory Dowd argues that most Native Americans involved in Pontiac's Rebellion were not immediately threatened with displacement by white settlers, and that historians have therefore overemphasized British colonial expansion as a cause of the war. Dowd believes that the presence, attitude, and policies of the British Army, which the Native Americans found threatening and insulting, were more important factors.

Also contributing to the outbreak of war was a religious awakening which swept through Native settlements in the early 1760s. The movement was fed by discontent with the British as well as food shortages and epidemic disease. The most influential individual in this phenomenon was Neolin

Neolin

Neolin was a prophet of the Lenni Lenape, who was derided by the British as "The Imposter." Beginning in 1762, Neolin believed that the native people needed to reject European goods and abandon dependency on foreign settlers in order to return to a more traditional lifestyle. He made arguments...

, known as the "Delaware Prophet", who called upon Native Americans to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the whites. Merging elements

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

from Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

into traditional religious beliefs, Neolin told listeners that the Master of Life

Great Spirit

The Great Spirit, also called Wakan Tanka among the Sioux, the Creator or the Great Maker in English, and Gitchi Manitou in Algonquian, is a conception of a supreme being prevalent among some Native American and First Nations cultures...

was displeased with the Native Americans for taking up the bad habits of the white men, and that the British posed a threat to their very existence. "If you suffer the English among you," said Neolin, "you are dead men. Sickness, smallpox, and their poison [alcohol] will destroy you entirely." It was a powerful message for a people whose world was being changed by forces that seemed beyond their control.

Outbreak of war, 1763

Planning the war

Although fighting in Pontiac's Rebellion began in 1763, rumors reached British officials as early as 1761 that discontented Native Americans were planning an attack. Senecas of the Ohio Country (Mingos) circulated messages ("war belts" made of wampumWampum

Wampum are traditional, sacred shell beads of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of the indigenous people of North America. Wampum include the white shell beads fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell; and the white and purple beads made from the quahog, or Western North Atlantic...

) which called for the tribes to form a confederacy and drive away the British. The Mingos, led by Guyasuta and Tahaiadoris, were concerned about being surrounded by British forts. Similar war belts originated from Detroit and the Illinois Country. The Native Americans were not unified, however, and in June 1761, Native Americans at Detroit informed the British commander of the Seneca plot. After William Johnson held a large council with the tribes at Detroit in September 1761 a tenuous peace was maintained, but war belts continued to circulate. Violence finally erupted after the Native Americans learned in early 1763 of the imminent French cession of the pays d'en haut to the British.

The war began at Fort Detroit under the leadership of Pontiac, and quickly spread throughout the region. Eight British forts were taken; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac portrayed these attacks as a coordinated operation planned by Pontiac. Parkman's interpretation remains well known, but other historians have since argued that there is no clear evidence that the attacks were part of a master plan or overall "conspiracy". The prevailing view among scholars today is that, rather than being planned in advance, the uprising spread as word of Pontiac's actions at Detroit traveled throughout the pays d'en haut, inspiring already discontented Native Americans to join the revolt. The attacks on British forts were not simultaneous: most Ohio Native Americans did not enter the war until nearly a month after the beginning of Pontiac's siege at Detroit.

Parkman also believed that Pontiac's War had been secretly instigated by French colonists

Habitants

Habitants is the name used to refer to both the French settlers and the inhabitants of French origin who farmed the land along the two shores of the St. Lawrence Gulf and River in what is the present-day Province of Quebec in Canada...

who were stirring up the Native Americans in order to make trouble for the British. This belief was widely held by British officials at the time, but subsequent historians have found no evidence of official French involvement in the uprising. (The rumor of French instigation arose in part because French war belts from the Seven Years' War were still in circulation in some Native villages.) Rather than the French stirring up the Native Americans, some historians now argue that the Native Americans were trying to stir up the French. Pontiac and other native leaders frequently spoke of the imminent return of French power and the revival of the Franco-Native alliance; Pontiac even flew a French flag in his village. All of this was apparently intended to inspire the French to rejoin the struggle against the British. Although some French colonists and traders supported the uprising, the war was initiated and conducted by Native Americans who had Native—not French—objectives.

Middleton (2007) argues that Pontiac's vision, courage, persistence, and organizational abilities allowed him to activate a remarkable coalition of Indian nations prepared to fight successfully against the British. Though the idea to liberate Native Americans west of the Alleghany Mountains did not originate with him but with two Seneca leaders, by February 1763 Pontiac appeared to embrace the idea. At an emergency council meeting, Pontiac clarified his military support of the broad Seneca plan and worked to galvanize other nations into the military operation that he helped lead, in direct contradiction to traditional Indian leadership and tribal structure.

Siege of Fort Detroit

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council about 10 miles (16.1 km) below the settlement of DetroitDetroit, Michigan

Detroit is the major city among the primary cultural, financial, and transportation centers in the Metro Detroit area, a region of 5.2 million people. As the seat of Wayne County, the city of Detroit is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan and serves as a major port on the Detroit River...

. Using the teachings of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

s, Potawatomi

Potawatomi

The Potawatomi are a Native American people of the upper Mississippi River region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a member of the Algonquian family. In the Potawatomi language, they generally call themselves Bodéwadmi, a name that means "keepers of the fire" and that was applied...

s, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit

Fort Detroit

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or Fort Détroit was a fort established by the French officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac in 1701. The location of the former fort is now in the city of Detroit in the U.S...

. On May 1, Pontiac visited the fort with 50 Ottawas in order to assess the strength of the garrison. According to a French chronicler, in a second council Pontiac proclaimed:

It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have done from our brothers, the French.... Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and wait no longer. Nothing prevents us; they are few in numbers, and we can accomplish it.

Hoping to take the stronghold by surprise, on May 7 Pontiac entered Fort Detroit with about 300 men carrying concealed weapons. The British had learned of Pontiac's plan, however, and were armed and ready. His tactic foiled, Pontiac withdrew after a brief council and, two days later, laid siege to the fort. Pontiac and his allies killed all of the British soldiers and settlers they could find outside of the fort, including women and children. One of the soldiers was ritually cannibalized

Cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh of other human beings. It is also called anthropophagy...

, as was the custom in some Great Lakes Native cultures. The violence was directed at the British; French colonists were generally left alone. Eventually more than 900 warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege. Meanwhile, on 28 May a British supply column from Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara

Fort Niagara is a fortification originally built to protect the interests of New France in North America. It is located near Youngstown, New York, on the eastern bank of the Niagara River at its mouth, on Lake Ontario.-Origin:...

led by Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

Abraham Cuyler was ambushed and defeated at Point Pelee

Point Pelee National Park

-See also:*National Parks of Canada*List of National Parks of Canada*Long Point-External links:**...

.

Battle of Bloody Run

The Battle of Bloody Run was fought during Pontiac's Rebellion on July 31, 1763. In an attempt to break Pontiac's siege of Fort Detroit, about 250 British troops attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiac's encampment....

on July 31, 1763. Nevertheless, the situation at Fort Detroit remained a stalemate, and Pontiac's influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Native Americans began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. On October 31, 1763, finally convinced that the French in Illinois would not come to his aid at Detroit, Pontiac lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River

Maumee River

The Maumee River is a river in northwestern Ohio and northeastern Indiana in the United States. It is formed at Fort Wayne, Indiana by the confluence of the St. Joseph and St. Marys rivers, and meanders northeastwardly for through an agricultural region of glacial moraines before flowing into the...

, where he continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.

Small forts taken

Before other British outposts had learned about Pontiac's siege at Detroit, Native Americans captured five small forts in a series of attacks between May 16 and June 2. The first to be taken was Fort SanduskyFort Sandusky

Fort Sandusky was a small British fort in the Ohio Country, on the shore of Lake Erie in present-day Ohio, which was captured and destroyed by American Indians during Pontiac's Rebellion....

, a small blockhouse

Blockhouse

In military science, a blockhouse is a small, isolated fort in the form of a single building. It serves as a defensive strong point against any enemy that does not possess siege equipment or, in modern times, artillery...

on the shore of Lake Erie

Lake Erie

Lake Erie is the fourth largest lake of the five Great Lakes in North America, and the tenth largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has the shortest average water residence time. It is bounded on the north by the...

. It had been built in 1761 by order of General Amherst, despite the objections of local Wyandots, who in 1762 warned the commander that they would soon burn it down. On May 16, 1763, a group of Wyandots gained entry under the pretense of holding a council, the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit nine days earlier. They seized the commander and killed the other 15 soldiers, as well as British traders at the fort. These were among the first of about 100 traders who were killed in the early stages of the war. The dead were ritually scalped

Scalping

Scalping is the act of removing another person's scalp or a portion of their scalp, either from a dead body or from a living person. The initial purpose of scalping was to provide a trophy of battle or portable proof of a combatant's prowess in war...

and the fort—as the Wyandots had warned a year earlier—was burned to the ground.

Fort St. Joseph

Fort St. Joseph (Niles)

Fort Saint Joseph was a fort established on land granted to the Jesuits by King Louis XIV; it was located on what is now the south side of the present-day town of Niles, Michigan. Père Claude-Jean Allouez established the Mission de Saint-Joseph in the 1680s...

(the site of present-day Niles

Niles, Michigan

Niles is a city in Berrien and Cass counties in the U.S. state of Michigan, near South Bend, Indiana. The population was 11,600 at the 2010 census. It is the greater populated of two principal cities of and included in the Niles-Benton Harbor, Michigan Metropolitan Statistical Area, which has a...

, Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

) was captured on May 25, 1763, by the same method as at Sandusky. Potawatomis seized the commander and killed most of the 15-man garrison outright. Fort Miami

Forts of Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne in modern Fort Wayne, Indiana, was established by Captain Jean François Hamtramck under orders from General "Mad" Anthony Wayne as part of the campaign against the Indians of the area. It was named after General Wayne, who was victorious at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne may have...

(on the site of present Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in the US state of Indiana and the county seat of Allen County. The population was 253,691 at the 2010 Census making it the 74th largest city in the United States and the second largest in Indiana...

, Indiana

Indiana