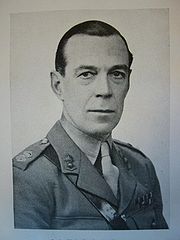

Philip Toosey

Encyclopedia

Brigadier

Brigadier is a senior military rank, the meaning of which is somewhat different in different military services. The brigadier rank is generally superior to the rank of colonel, and subordinate to major general....

Sir Philip John Denton Toosey, CBE

Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is an order of chivalry established on 4 June 1917 by George V of the United Kingdom. The Order comprises five classes in civil and military divisions...

, DSO

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

, TD

Territorial Decoration

The Territorial Decoration was a medal of the United Kingdom awarded for long service in the Territorial Force and its successor, the Territorial Army...

, JP

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

, LLD

Legum Doctor

Legum Doctor is a doctorate-level academic degree in law, or an honorary doctorate, depending on the jurisdiction. The double L in the abbreviation refers to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both Canon Law and Civil Law, the double L indicating the plural, Doctor of both...

{Liverpool University} (12 August 1904 – 22 December 1975) was (as a Lieutenant-Colonel) the senior Allied officer in the Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese prisoner-of-war camp at Tha Maa Kham (known as Tamarkan) in Thailand

Thailand

Thailand , officially the Kingdom of Thailand , formerly known as Siam , is a country located at the centre of the Indochina peninsula and Southeast Asia. It is bordered to the north by Burma and Laos, to the east by Laos and Cambodia, to the south by the Gulf of Thailand and Malaysia, and to the...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. The men at this camp built the Bridge on the River Kwai which was described in a book by Pierre Boulle

Pierre Boulle

Pierre Boulle was a French novelist largely known for two famous works, The Bridge over the River Kwai and Planet of the Apes .-Biography:...

and later in an Oscar-winning film in which Alec Guinness

Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness, CH, CBE was an English actor. He was featured in several of the Ealing Comedies, including Kind Hearts and Coronets in which he played eight different characters. He later won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai...

played the senior British officer. Both the book and film outraged former prisoners because Toosey did not collaborate

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

with the enemy, unlike the fictional Colonel Nicholson.

Early life

Toosey was born in Upton Road, OxtonOxton, Merseyside

Oxton is a suburb of Birkenhead, on the Wirral Peninsula, England. Administratively it is a ward of the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral. Originally a village in its own right, it became part of the Municipal Borough of Birkenhead upon its creation in 1877...

, Birkenhead

Birkenhead

Birkenhead is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral in Merseyside, England. It is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the west bank of the River Mersey, opposite the city of Liverpool...

. He was educated at home until the age of nine, then at Birkenhead School

Birkenhead School

Birkenhead School is an independent, selective, co-educational school located on the Wirral Peninsula in the northwest of England. It is a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference.-Overview:The school is subdivided into...

to the age of thirteen and then at Gresham's School

Gresham's School

Gresham’s School is an independent coeducational boarding school in Holt in North Norfolk, England, a member of the HMC.The school was founded in 1555 by Sir John Gresham as a free grammar school for forty boys, following King Henry VIII's dissolution of the Augustinian priory at Beeston Regis...

, Holt, Norfolk

Holt, Norfolk

Holt is a market town and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The town is north of the city of Norwich, west of Cromer and east of King's Lynn. The town is on the route of the A148 King's Lynn to Cromer road. The nearest railway station is in the town of Sheringham where access to the...

. His father forbade him to accept a scholarship to Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

and so he was apprenticed to a firm of Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

cotton merchants. In 1927 he was commissioned into 59th (4th West Lancs) Medium Brigade RA of the Territorial Army. In 1929 he joined Baring Brothers

Barings Bank

Barings Bank was the oldest merchant bank in London until its collapse in 1995 after one of the bank's employees, Nick Leeson, lost £827 million due to speculative investing, primarily in futures contracts, at the bank's Singapore office.-History:-1762–1890:Barings Bank was founded in 1762 as the...

, merchant bankers as Assistant Agent. His commanding officer in the TA, Colonel Alan Tod, was the Liverpool Agent at the time. He married Muriel Alexandra (Alex) Eccles on 27 July 1932 and they had two sons and a daughter.

Army career

In August 1939 he was mobilized and saw brief action in BelgiumBelgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

in May 1940 before retreating back into France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. He was evacuated from Dunkirk. Following a course at the Senior Officers' School, he commanded and trained a home defence battery at Cambridge. In 1941, promoted to lieutenant-colonel, he was appointed to command the 135th Hertfordshire Yeomanry

Hertfordshire Yeomanry

The Hertfordshire Yeomanry is a British Army unit specializing in artillery and yeomanry that can trace its formation to the late 18th century. First seeing service in the Boer War, it subsequently served in both World Wars....

Field Artillery Regiment. In October 1941, his unit was shipped to the Far East. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

for heroism during the defence of Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

. Because of his qualities of leadership, his superiors ordered him on 12 February 1942 to join the evacuation of Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

, but Toosey refused so that he could remain with his men during their captivity.

Building the bridges

Geneva Convention (1929)

The Geneva Convention was signed at Geneva, July 27, 1929. Its official name is the Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva July 27, 1929. It entered into force 19 June 1931. It is this version of the Geneva Conventions which covered the treatment of prisoners of war...

) to build railway bridges over the Khwae Yai

Khwae Yai River

The Khwae Yai River , also known as the Si Sawat , is a river in western Thailand. It flows for about 380 kilometres through Sangkhla Buri, Si Sawat, and Mueang Districts of Kanchanaburi Province, where it merges with the Khwae Noi to form the Mae Klong River at Pak Phraek subdistrict.The famous...

near where it joins the Khwae Noi to form the Mae Klong

Mae Klong

The Mae Klong is a river in western Thailand. The river begins at the confluence of the Khwae Noi or Khwae Sai Yok and the Khwae Yai River or Khwae Si Sawat in Kanchanaburi, pass Ratchaburi Province and empties into the Gulf of Thailand in Samut Songkhram....

in Thailand.. The Khwae Mae Khlong above the confluence was renamed the Khwae Yai in 1960. This was part of a project to link existing Thai and Burmese railway lines to create a route from Bangkok

Bangkok

Bangkok is the capital and largest urban area city in Thailand. It is known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon or simply Krung Thep , meaning "city of angels." The full name of Bangkok is Krung Thep Mahanakhon Amon Rattanakosin Mahintharayutthaya Mahadilok Phop Noppharat Ratchathani Burirom...

to Rangoon to support the Japanese occupation of Burma. About a hundred thousand conscripted Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

n labourers and 12,000 prisoners of war died on the whole project, which was nicknamed the Death Railway

Death Railway

The Burma Railway, also known as the Death Railway, the Thailand–Burma Railway and similar names, was a railway between Bangkok, Thailand, and Rangoon, Burma , built by the Empire of Japan during World War II, to support its forces in the Burma campaign.Forced labour was used in its construction...

.

A camp was established at Tamarkan, which is about five kilometres from Kanchanaburi

Kanchanaburi

Kanchanaburi ) is a town in the west of Thailand and the capital of Kanchanaburi province. In 2006 it had a population of 31,327...

. In the Tamarkan camp, Toosey worked courageously to ensure that as many as possible of the 2,000 Allied prisoners would survive. He endured regular beatings when he complained of ill-treatment of prisoners, but as a skilled negotiator he was able to win many concessions from the Japanese by convincing them that this would speed the completion of the work. Toosey also organised the smuggling in of food and medicine, working with Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu

Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu

Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu was a Thai businessman, Kanchanaburi mayor and Seri Thai captain who smuggled supplies to the POWs of Tamarkan, while they were building the Death Railway between Bangkok and Rangoon during World War II. See also Philip Toosey....

. Boonpong was a Thai merchant who supplied camps at the southern end of the railway taking great risks and was honoured after the war.

Toosey maintained discipline in the camp and, where possible, cleanliness and hygiene. His policy was of unity and equality and so refused to allow a separate officers' mess or officers' accommodation. He also ordered his officers to intervene if necessary to protect the men. For his conduct in the camp, he won the undying respect of his men. He was considered by many to be the outstanding British officer on the railway.

Behind the backs of the Japanese, Toosey did everything possible to delay and sabotage the construction without endangering his men. Refusal to work would have meant instant execution. Termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures and the concrete was badly mixed. Toosey also helped organise a daring escape, at considerable cost to himself. (In the film the fictional colonel forbids escapes.) The two escaping officers had been given a month's rations and Toosey concealed their escape for 48 hours. After a month the two escapees were recaptured and bayoneted. Toosey was punished for concealing the escape.

The film portrays the Japanese as not being capable of designing a good bridge and so needed British expertise. This is incorrect; the Japanese army had excellent engineers who surprised their enemies by completing the railway within 16 months, albeit at vast human cost, the Japanese having relied upon Allied prisoners as slave laborers. British Army engineers had estimated five years.

Two bridges were built: a temporary wooden bridge and a few months later a permanent steel and concrete bridge which was completed in 1943. At the end of the film the wooden bridge is destroyed by a commando raid when actually, both bridges were used for two years until they were destroyed by Allied aerial bombing, the steel bridge first in June 1945; there had been seven previous bombing missions. The steel bridge has been repaired and is still in use today.

After the bridges

After completion of the steel bridge the majority of fit men were moved to camps further up the line. Toosey was ordered to organize Tamarkan as a hospital, which he did despite difficulties including minimal food and medical supplies. The Japanese considered it the best-run prisoner-of-war camp on the railway and gave him considerable autonomy. In December 1943 he was transferred to help run Nong Pladuk camp, and in December 1944 he was moved to the allied officers' camp at Kanchanaburi where he was the liaison officer with the Japanese.He and some other officers had been separated from his men at Nakhon Nayok camp and was being held there as a hostage when Japan surrendered in August 1945. At that time, Toosey weighed 105 pounds (47 kg); before the war he weighed 175 pounds. Despite his weak state, Toosey insisted on travelling 300 miles (500 km) into the jungle to oversee the liberation of his men.

After the war

After the war Toosey resumed his service with the Territorial Army and was promoted brigadier

Brigadier

Brigadier is a senior military rank, the meaning of which is somewhat different in different military services. The brigadier rank is generally superior to the rank of colonel, and subordinate to major general....

. He retired from the TA in 1954, and was awarded a CBE in 1955. Toosey also returned to banking with Barings in Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

and expanded their services greatly.

He worked for the veterans all his life, and in 1966 became President of the National Federation of Far East Prisoners of War

Far East Prisoners of War

Far East Prisoners of War is a term used in the United Kingdom to describe former British and Commonwealth prisoners of war held in the Far East during the Second World War...

.

The film The Bridge on the River Kwai

The Bridge on the River Kwai

The Bridge on the River Kwai is a 1957 British World War II film by David Lean based on The Bridge over the River Kwai by French writer Pierre Boulle. The film is a work of fiction but borrows the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–43 for its historical setting. It stars William...

was released in 1957. In the film, the senior British officer was portrayed as working with the Japanese. This was regarded by many former prisoners of war as a gross travesty of the truth. Toosey initially refused repeated requests by the veterans to speak out against the film, being much too modest to seek any glory or recognition for himself. Eventually he was persuaded to write a letter to the Daily Telegraph, which caused several other veterans to emphasise the injustice that had occurred. Nevertheless the film was highly successful and so formed the public perception of events at Tamarkan. As a result Toosey agreed several years later to be interviewed by Professor Peter Davies, providing 48 hours of taped interviews on the understanding that they were not to be published until after Toosey's death. Eventually Davies documented Toosey's achievements in a 1991 book entitled The Man Behind the Bridge (ISBN 0-485-11402-X) and a BBC Timewatch programme. A book by his oldest granddaughter, Julie Summers, The Colonel of Tamarkan, was published in 2005 (ISBN 0-7432-6350-2).

Toosey was a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

, High Sheriff of Lancashire

High Sheriff of Lancashire

The High Sheriff of Lancashire is an ancient officer, now largely ceremonial, granted to Lancashire, a county in North West England. High Shrievalties are the oldest secular titles under the Crown, in England and Wales...

for 1964, and raised funds for the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

The Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine is a research and teaching institution focused on neglected tropical diseases and the control of diseases caused by poverty. It is a registered charity affiliated to the University of Liverpool...

. In 1974 he was awarded an honorary LLD by Liverpool University and was knighted. Phil Toosey died on 22 December 1975. The Territorial Army Barracks on Aigburth Road in Liverpool was renamed The Brigadier Phillip Toosey Barracks. His ashes were buried in Landican Cemetery outside Birkenhead.