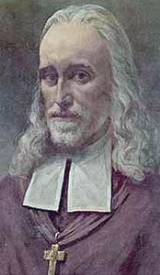

Oliver Plunkett

Encyclopedia

Saint

Oliver Plunkett (alternative spelling Plunket) (1 November 1629 – 1 July 1681) was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.

He maintained his duties in Ireland in the face of English persecution and was eventually arrested and tried for treason. He was brought from a prison cell in Dublin Castle to face trial in Dundalk, during which he made no objection to the all-Protestant jury. The prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court, so the trial soon collapsed. Because of a common belief that no jury in Ireland would ever convict him, irrespective of its makeup, Archbishop Plunkett was then transferred to face trial in Westminster Hall, London. His trial has often been described as a travesty of justice as he was again denied defending counsel, time to assemble his defence witnesses and he was also frustrated in his attempts to obtain the criminal records of those who were to give evidence against him. His servant James McKenna and a relative John Plunkett had travelled back to Ireland and failed within the time available to bring back witnesses and evidence for the defence. During the trial Archbishop Plunkett had disputed the right of the court to try him in England and he also drew attention to the criminal past of the witnesses, but all to no avail. Lord Chief Justice Pemberton addressing these complaints said to the accused, "Look you, Mr. Plunket, it is in vain for you to talk and make this discourse here now..." and later on again, “Look you Mr Plunket, don't mis-spend your own time; for the more you trifle in these things, the less time you will have for your defence". In passing judgement the Chief Justice said: “You have done as much as you could to dishonour God in this case; for the bottom of your treason was your setting up your false religion, than which there is not any thing more displeasing to God, or more pernicious to mankind in the world.”. The jury returned within fifteen minutes with a guilty verdict and Archbishop Plunkett replied: “Deo Gratias” (Latin for "Thanks be to God"). He was hanged, drawn and quartered

at Tyburn

on 1 July 1681, the last Roman Catholic martyr

to die in England. Oliver Plunkett was beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975, the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years.

, County Meath

, Ireland to well-to-do parents of Hiberno-Norman

origin. He was related by birth to a number of landed

families, such as the recently ennobled Earl of Roscommon

, as well as the long-established Earl of Fingall

, Lord Louth

and Lord Dunsany

. Until his sixteenth year, the boy's education was entrusted to his cousin Patrick Plunkett, Abbot of St Mary's, Dublin, and brother of the first Earl of Fingall

who later became bishop, successively, of Ardagh and Meath. As an aspirant to the priesthood, he set out for Rome in 1647, under the care of Father Pierfrancesco Scarampi

, of the Roman Oratory. At this time, the Irish Confederate Wars

were raging in Ireland; these were essentially conflicts between native Irish Roman Catholics, English, and Irish Anglicans and Protestants. Scarampi was the Papal envoy to the Roman Catholic movement known as the Confederation of Ireland

. Many of Plunkett's relatives were involved in this organisation

He was admitted to the Irish College in Rome and he proved to be an able pupil. He was ordained a priest in 1654, and deputed by the Irish bishops to act as their representative in Rome. Meanwhile, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

(1649–53) had defeated the Roman Catholic cause in Ireland and, in the aftermath, the public practice of Roman Catholicism was banned and Roman Catholic clergy were executed. As a result, it was impossible for Plunkett to return to Ireland for many years. He petitioned to remain in Rome and, in 1657, became a professor of theology. Throughout the period of the Commonwealth and the first years of Charles II

's reign, he successfully pleaded the cause of the Irish Roman Church, and also served as theological professor at the College of Propaganda Fide

. At the Congregation of Propaganda Fide on 9 July 1669, he was appointed Archbishop of Armagh, the Irish primatial see, and was consecrated on 30 November at Ghent

by the Bishop of Ghent

, He eventually set foot on Irish soil again on 7 March 1670, as the English Restoration

of 1660 had started on a tolerant basis. The pallium

was granted him in the Consistory

of 28 July 1670.

After arriving back in Ireland, he set about reorganising the ravaged Roman Church and built schools both for the young and for clergy, whom he found 'ignorant in moral theology and controversies'. He tackled drunkenness among the clergy, writing 'Let us remove this defect from an Irish priest, and he will be a saint'. The Penal Laws had been relaxed in line with the Declaration of Breda

in 1660 and he was able to establish a Jesuit College in Drogheda

in 1670. A year later 150 students attended the college, no fewer than 40 of whom were Protestant, making this college the first integrated school in Ireland.

On the enactment of the Test Act

On the enactment of the Test Act

in 1673, which Plunkett would not agree to for doctrinal reasons, the college was levelled to the ground. Plunkett went into hiding, traveling only in disguise, and refused a government edict to register at a seaport to await passage into exile. In 1678, the so-called Popish Plot

, concocted in England by Titus Oates

, led to further anti-Roman Catholicism. Archbishop Peter Talbot

of Dublin was arrested, and Plunkett again went into hiding. The Privy Council

in London was told he had plotted a French invasion.

Despite being on the run and with a price on his head, he refused to leave his flock. He was arrested in Dublin in December 1679 and imprisoned in Dublin Castle

, where he gave absolution to the dying Talbot. At some point before his final incarceration

, he took refuge in a church that once stood in the townland of Killartry in County Louth, in the parish of Clogherhead

, seven miles outside of Drogheda. He was tried at Dundalk

for conspiring against the state by plotting to bring 20,000 French soldiers into the country, and for levying a tax on his clergy to support 70,000 men for rebellion. Though this was unproven, some in government circles were worried about, and some used the excuse, that another rebellion

was being planned.

Lord Shaftesbury knew Oliver Plunkett would never be convicted in Ireland and had him moved to Newgate Prison

, London. The first grand jury found no true bill, but he was not released. The second trial was claimed to be a kangaroo court

; Lord Campbell, writing of the judge, Sir Francis Pemberton

, claimed it a disgrace to himself and his country. Plunkett was found guilty of high treason on June 1681 "for promoting the Roman faith," and was condemned to a gruesome death.

On 1 July 1681, Plunkett became the last Roman Catholic martyr

On 1 July 1681, Plunkett became the last Roman Catholic martyr

to die in England when he was hanged, drawn and quartered

at Tyburn

. His body was initially buried in two tin boxes next to five Jesuits who had died before in the courtyard of St Giles

. The remains were exhumed in 1683 and moved to the Benedictine monastery at Lamspringe

, near Hildesheim

in Germany. The head was brought to Rome, and from there to Armagh

and eventually to Drogheda

where, since 29 June 1921, it has rested in Saint Peter's Church

. Most of the body was brought to Downside Abbey

, England, where the major part is located today, with some parts remaining at Lamspringe. Some relic

s were brought to Ireland in May 1975, while others are in England, France, Germany, the United States, and Australia.

Oliver Plunkett was beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975, the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years, and the first of the Irish martyrs

to be beatified. For the canonisation, the customary second miracle was waived. (He has since been followed by 17 other Irish martyrs who were beatified by Pope John Paul II

in 1992. Among them were Archbishop

Dermot O'Hurley

, Margaret Ball

, and the Wexford Martyrs

.)

Nevertheless, his ministry during its time was most successful and he confirmed over 48,000 people over a four-year period. In 1997, he became a patron saint for peace and reconciliation in Ireland, adopted by the prayer group campaigning for peace in Ireland, 'St Oliver Plunkett for Peace and Reconciliation'.

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

Oliver Plunkett (alternative spelling Plunket) (1 November 1629 – 1 July 1681) was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland.

He maintained his duties in Ireland in the face of English persecution and was eventually arrested and tried for treason. He was brought from a prison cell in Dublin Castle to face trial in Dundalk, during which he made no objection to the all-Protestant jury. The prosecution witnesses were themselves wanted men and afraid to turn up in court, so the trial soon collapsed. Because of a common belief that no jury in Ireland would ever convict him, irrespective of its makeup, Archbishop Plunkett was then transferred to face trial in Westminster Hall, London. His trial has often been described as a travesty of justice as he was again denied defending counsel, time to assemble his defence witnesses and he was also frustrated in his attempts to obtain the criminal records of those who were to give evidence against him. His servant James McKenna and a relative John Plunkett had travelled back to Ireland and failed within the time available to bring back witnesses and evidence for the defence. During the trial Archbishop Plunkett had disputed the right of the court to try him in England and he also drew attention to the criminal past of the witnesses, but all to no avail. Lord Chief Justice Pemberton addressing these complaints said to the accused, "Look you, Mr. Plunket, it is in vain for you to talk and make this discourse here now..." and later on again, “Look you Mr Plunket, don't mis-spend your own time; for the more you trifle in these things, the less time you will have for your defence". In passing judgement the Chief Justice said: “You have done as much as you could to dishonour God in this case; for the bottom of your treason was your setting up your false religion, than which there is not any thing more displeasing to God, or more pernicious to mankind in the world.”. The jury returned within fifteen minutes with a guilty verdict and Archbishop Plunkett replied: “Deo Gratias” (Latin for "Thanks be to God"). He was hanged, drawn and quartered

Hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I...

at Tyburn

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

on 1 July 1681, the last Roman Catholic martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

to die in England. Oliver Plunkett was beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975, the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years.

Life

Oliver Plunkett was born in 1629 in LoughcrewLoughcrew

Loughcrew is near Oldcastle, County Meath, Ireland. . Loughcrew is a site of considerable historical importance in Ireland...

, County Meath

County Meath

County Meath is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the ancient Kingdom of Mide . Meath County Council is the local authority for the county...

, Ireland to well-to-do parents of Hiberno-Norman

Hiberno-Norman

The Hiberno-Normans are those Norman lords who settled in Ireland who admitted little if any real fealty to the Anglo-Norman settlers in England, and who soon began to interact and intermarry with the Gaelic nobility of Ireland. The term embraces both their origins as a distinct community with...

origin. He was related by birth to a number of landed

Landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant . When a juristic person is in this position, the term landlord is used. Other terms include lessor and owner...

families, such as the recently ennobled Earl of Roscommon

Earl of Roscommon

Earl of Roscommon was a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created on 5 August 1622 for James Dillon, 1st Baron Dillon. He had already been created Baron Dillon on 24 January 1619, also in the Peerage of Ireland. The fourth Earl was a courtier, poet and critic. The titles became dormant on the...

, as well as the long-established Earl of Fingall

Earl of Fingall

Baron Killeen and Earl of Fingall were titles in the Peerage of Ireland. Baron Fingall was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom...

, Lord Louth

Baron Louth

Baron Louth is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1541 for Sir Oliver Plunkett. His great-great-great-grandson, the seventh Baron, served as Lord Lieutenant of County Louth. However, he later supported King James II and was outlawed. His great-great-grandson, the eleventh Baron,...

and Lord Dunsany

Baron Dunsany

The title Baron of Dunsany or, more commonly, Lord Dunsany, is one of the oldest dignities in the Peerage of Ireland, one of just a handful of 13th to 15th century titles still extant, having had 20 holders to date...

. Until his sixteenth year, the boy's education was entrusted to his cousin Patrick Plunkett, Abbot of St Mary's, Dublin, and brother of the first Earl of Fingall

Earl of Fingall

Baron Killeen and Earl of Fingall were titles in the Peerage of Ireland. Baron Fingall was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom...

who later became bishop, successively, of Ardagh and Meath. As an aspirant to the priesthood, he set out for Rome in 1647, under the care of Father Pierfrancesco Scarampi

Pierfrancesco Scarampi

Pierfrancesco Scarampi was a Roman Catholic oratorian and Papal envoy.-Early life and ordination:Scarampi was born into the noble Scarampi family in the Marquisate of Montferrat, today a part of Piedmont, in 1596. He was destined by his parents for the military career, but during a visit to the...

, of the Roman Oratory. At this time, the Irish Confederate Wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

were raging in Ireland; these were essentially conflicts between native Irish Roman Catholics, English, and Irish Anglicans and Protestants. Scarampi was the Papal envoy to the Roman Catholic movement known as the Confederation of Ireland

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

. Many of Plunkett's relatives were involved in this organisation

He was admitted to the Irish College in Rome and he proved to be an able pupil. He was ordained a priest in 1654, and deputed by the Irish bishops to act as their representative in Rome. Meanwhile, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

(1649–53) had defeated the Roman Catholic cause in Ireland and, in the aftermath, the public practice of Roman Catholicism was banned and Roman Catholic clergy were executed. As a result, it was impossible for Plunkett to return to Ireland for many years. He petitioned to remain in Rome and, in 1657, became a professor of theology. Throughout the period of the Commonwealth and the first years of Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

's reign, he successfully pleaded the cause of the Irish Roman Church, and also served as theological professor at the College of Propaganda Fide

Roman Colleges

Note: This article is based on the "Catholic Encyclopedia" 1913 and contains a large amount of out-dated information throughout, including the numbers of students...

. At the Congregation of Propaganda Fide on 9 July 1669, he was appointed Archbishop of Armagh, the Irish primatial see, and was consecrated on 30 November at Ghent

Ghent

Ghent is a city and a municipality located in the Flemish region of Belgium. It is the capital and biggest city of the East Flanders province. The city started as a settlement at the confluence of the Rivers Scheldt and Lys and in the Middle Ages became one of the largest and richest cities of...

by the Bishop of Ghent

Bishop of Ghent

The Bishop of Ghent is the Ordinary of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gent, which comprises the entire province of East Flanders as well as the Antwerp municipalities of Zwijndrecht and Burcht. The current Bishop of Ghent is Mgr...

, He eventually set foot on Irish soil again on 7 March 1670, as the English Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

of 1660 had started on a tolerant basis. The pallium

Pallium

The pallium is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Roman Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the Pope, but for many centuries bestowed by him on metropolitans and primates as a symbol of the jurisdiction delegated to them by the Holy See. In that context it has always remained unambiguously...

was granted him in the Consistory

Consistory

-Antiquity:Originally, the Latin word consistorium meant simply 'sitting together', just as the Greek synedrion ....

of 28 July 1670.

After arriving back in Ireland, he set about reorganising the ravaged Roman Church and built schools both for the young and for clergy, whom he found 'ignorant in moral theology and controversies'. He tackled drunkenness among the clergy, writing 'Let us remove this defect from an Irish priest, and he will be a saint'. The Penal Laws had been relaxed in line with the Declaration of Breda

Declaration of Breda

The Declaration of Breda was a proclamation by Charles II of England in which he promised a general pardon for crimes committed during the English Civil War and the Interregnum for all those who recognised Charles as the lawful king; the retention by the current owners of property purchased during...

in 1660 and he was able to establish a Jesuit College in Drogheda

Drogheda

Drogheda is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 56 km north of Dublin. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea....

in 1670. A year later 150 students attended the college, no fewer than 40 of whom were Protestant, making this college the first integrated school in Ireland.

Persecution

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

in 1673, which Plunkett would not agree to for doctrinal reasons, the college was levelled to the ground. Plunkett went into hiding, traveling only in disguise, and refused a government edict to register at a seaport to await passage into exile. In 1678, the so-called Popish Plot

Popish Plot

The Popish Plot was a fictitious conspiracy concocted by Titus Oates that gripped England, Wales and Scotland in Anti-Catholic hysteria between 1678 and 1681. Oates alleged that there existed an extensive Catholic conspiracy to assassinate Charles II, accusations that led to the execution of at...

, concocted in England by Titus Oates

Titus Oates

Titus Oates was an English perjurer who fabricated the "Popish Plot", a supposed Catholic conspiracy to kill King Charles II.-Early life:...

, led to further anti-Roman Catholicism. Archbishop Peter Talbot

Archbishop Peter Talbot

Peter Talbot was the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin from 1669 to his death.- Early life :Talbot was born at Malahide, County Dublin, Ireland, in 1620. At an early age he entered the Society of Jesus in Portugal. He was ordained a priest at Rome, and for some years thereafter held the chair...

of Dublin was arrested, and Plunkett again went into hiding. The Privy Council

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

in London was told he had plotted a French invasion.

Despite being on the run and with a price on his head, he refused to leave his flock. He was arrested in Dublin in December 1679 and imprisoned in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

, where he gave absolution to the dying Talbot. At some point before his final incarceration

Incarceration

Incarceration is the detention of a person in prison, typically as punishment for a crime .People are most commonly incarcerated upon suspicion or conviction of committing a crime, and different jurisdictions have differing laws governing the function of incarceration within a larger system of...

, he took refuge in a church that once stood in the townland of Killartry in County Louth, in the parish of Clogherhead

Clogherhead

Clogherhead is a fishing village in County Louth, Ireland. Located in a picturesque natural bay on the East Coast it is bordered by the villages of Annagassan to the north and Termonfeckin to the south. with an administrative population per the 2011 Census of 3026, it is in the townlands of...

, seven miles outside of Drogheda. He was tried at Dundalk

Dundalk

Dundalk is the county town of County Louth in Ireland. It is situated where the Castletown River flows into Dundalk Bay. The town is close to the border with Northern Ireland and equi-distant from Dublin and Belfast. The town's name, which was historically written as Dundalgan, has associations...

for conspiring against the state by plotting to bring 20,000 French soldiers into the country, and for levying a tax on his clergy to support 70,000 men for rebellion. Though this was unproven, some in government circles were worried about, and some used the excuse, that another rebellion

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

was being planned.

Lord Shaftesbury knew Oliver Plunkett would never be convicted in Ireland and had him moved to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

, London. The first grand jury found no true bill, but he was not released. The second trial was claimed to be a kangaroo court

Kangaroo court

A kangaroo court is "a mock court in which the principles of law and justice are disregarded or perverted".The outcome of a trial by kangaroo court is essentially determined in advance, usually for the purpose of ensuring conviction, either by going through the motions of manipulated procedure or...

; Lord Campbell, writing of the judge, Sir Francis Pemberton

Francis Pemberton

Sir Francis Pemberton was an English judge and briefly Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench in the course of a turbulent career.-Early life:...

, claimed it a disgrace to himself and his country. Plunkett was found guilty of high treason on June 1681 "for promoting the Roman faith," and was condemned to a gruesome death.

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

to die in England when he was hanged, drawn and quartered

Hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I...

at Tyburn

Tyburn, London

Tyburn was a village in the county of Middlesex close to the current location of Marble Arch in present-day London. It took its name from the Tyburn or Teo Bourne 'boundary stream', a tributary of the River Thames which is now completely covered over between its source and its outfall into the...

. His body was initially buried in two tin boxes next to five Jesuits who had died before in the courtyard of St Giles

St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields, Holborn, is a church in the London Borough of Camden, in the West End. It is close to the Centre Point office tower and the Tottenham Court Road tube station. The church is part of the Diocese of London within the Church of England...

. The remains were exhumed in 1683 and moved to the Benedictine monastery at Lamspringe

Lamspringe

Lamspringe is a village and a municipality in the district of Hildesheim, in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated approx. 20 km south of Hildesheim....

, near Hildesheim

Hildesheim

Hildesheim is a city in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is located in the district of Hildesheim, about 30 km southeast of Hanover on the banks of the Innerste river, which is a small tributary of the Leine river...

in Germany. The head was brought to Rome, and from there to Armagh

Armagh

Armagh is a large settlement in Northern Ireland, and the county town of County Armagh. It is a site of historical importance for both Celtic paganism and Christianity and is the seat, for both the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of Ireland, of the Archbishop of Armagh...

and eventually to Drogheda

Drogheda

Drogheda is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 56 km north of Dublin. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea....

where, since 29 June 1921, it has rested in Saint Peter's Church

St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, Drogheda

St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church is a Roman Catholic church located in Drogheda, Ireland.The first Church on the site was built in 1791 to a design by Francis Johnston and was partly incorporated into the present building one hundred years later. The facade is an imposing structure in the Gothic...

. Most of the body was brought to Downside Abbey

Downside Abbey

The Basilica of St Gregory the Great at Downside, commonly known as Downside Abbey, is a Roman Catholic Benedictine monastery and the Senior House of the English Benedictine Congregation. One of its main apostolates is a school for children aged nine to eighteen...

, England, where the major part is located today, with some parts remaining at Lamspringe. Some relic

Relic

In religion, a relic is a part of the body of a saint or a venerated person, or else another type of ancient religious object, carefully preserved for purposes of veneration or as a tangible memorial...

s were brought to Ireland in May 1975, while others are in England, France, Germany, the United States, and Australia.

Oliver Plunkett was beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975, the first new Irish saint for almost seven hundred years, and the first of the Irish martyrs

Irish Martyrs

Irish Catholic Martyrs were dozens of people who have been sanctified in varying degrees for dying for their Roman Catholic faith between 1537 and 1714 in Ireland.-Causes:...

to be beatified. For the canonisation, the customary second miracle was waived. (He has since been followed by 17 other Irish martyrs who were beatified by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

in 1992. Among them were Archbishop

Archbishop

An archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop...

Dermot O'Hurley

Dermot O'Hurley

Blessed Dermot O'Hurley - in Irish Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile - was a Roman Catholic Archbishop of Cashel during the reign of Elizabeth I who was put to death for treason...

, Margaret Ball

Margaret Ball

Blessed Margaret Ball was born Margaret Birmingham near Skryne in County Meath, and died of deprivation in the dungeons of Dublin Castle. She was the wife of the Mayor of Dublin in 1553. She was beatified in 1992.-Early life:...

, and the Wexford Martyrs

Wexford Martyrs

The Wexford Martyrs were Matthew Lambert, Robert Tyler, Edward Cheevers, Patrick Cavanagh and two unknown individuals. In 1581, they were found guilty of treason for aiding in the escape of James Eustace, 3rd Viscount Baltinglass and refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy and declare Elizabeth I of...

.)

Nevertheless, his ministry during its time was most successful and he confirmed over 48,000 people over a four-year period. In 1997, he became a patron saint for peace and reconciliation in Ireland, adopted by the prayer group campaigning for peace in Ireland, 'St Oliver Plunkett for Peace and Reconciliation'.

Timeline of events

- 4 March 1651 – tonsureTonsureTonsure is the traditional practice of Christian churches of cutting or shaving the hair from the scalp of clerics, monastics, and, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, all baptized members...

& minor ordersMinor ordersThe minor orders are the lowest ranks in the Christian clergy. The most recognized minor orders are porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. In the Latin rite Catholic Church, the minor orders were in most cases replaced by "instituted" ministries of lector and acolyte, though communities that use... - 20 December 1653 – ordained as subdeaconSubdeacon-Subdeacons in the Orthodox Church:A subdeacon or hypodeacon is the highest of the minor orders of clergy in the Orthodox Church. This order is higher than the reader and lower than the deacon.-Canonical Discipline:...

- 26 December 1653 – ordained as deaconDeaconDeacon is a ministry in the Christian Church that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions...

- 1 January 1654 – ordained as priestPriestA priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities...

in Rome - November 1657 – appointed Professor of Theology at Propaganda college, Rome

- 1 December 1669 – consecrated as archbishopArchbishopAn archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop...

- 7 March 1670 – landed at Ringsend, Dublin, ending 23 years of self imposed exile abroad

- 6 December 1679 – arrested

- 23 July 1680 – trial

- 24 October 1680 – transfer from Ireland to London

- 8 June 1681 – trial

- 15 June 1681 – sentenced to death

- 1 July 1681 (OSOld Style and New Style datesOld Style and New Style are used in English language historical studies either to indicate that the start of the Julian year has been adjusted to start on 1 January even though documents written at the time use a different start of year ; or to indicate that a date conforms to the Julian...

) = 11 July 1681 (NS) – hanged, drawn, quarteredHanged, drawn and quarteredTo be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I...

(the punishment for treason against the state), beheaded - 9 December 1886 declared venerableVenerableThe Venerable is used as a style or epithet in several Christian churches. It is also the common English-language translation of a number of Buddhist titles.-Roman Catholic:...

- 17 March 1918 – declaration of martyrdom

- Pentecost Sunday, 23 May 1920 – beatified

- 12 October 1975 – canonized

In popular culture

- In Harold PinterHarold PinterHarold Pinter, CH, CBE was a Nobel Prize–winning English playwright and screenwriter. One of the most influential modern British dramatists, his writing career spanned more than 50 years. His best-known plays include The Birthday Party , The Homecoming , and Betrayal , each of which he adapted to...

's The Birthday PartyThe Birthday Party (play)The Birthday Party is the first full-length play by Harold Pinter and one of Pinter's best-known and most-frequently performed plays...

, McCann asks Stanley "What about the blessed Oliver Plunkett?" - In J. P. DonleavyJ. P. DonleavyJames Patrick Donleavy is an Irish American author, born to Irish immigrants. He served in the U.S. Navy during World War II after which he moved to Ireland. In 1946 he began studies at Trinity College, Dublin, but left before taking a degree...

's The Ginger ManThe Ginger ManThe Ginger Man is a 1955 novel by J. P. Donleavy.First published in Paris, the novel is set in Dublin, Ireland, in post war 1947. Upon its publication, it was banned in the Republic of Ireland and the United States of America for obscenity....

, Sebastian Dangerfield repeatedly calls on the name of "the Blessed Oliver" and, towards the end of the book, receives a wooden carving of the saint's head. - In David CaffreyDavid CaffreyDavid Caffrey is an Irish-born film director. His most recent film is Grand Theft Parsons starring Johnny Knoxville and Christina Applegate. The film is an account of an urban myth about the death of folk rock legend, Gram Parsons.-Filmography:...

's 2001 film On The NoseOn the NoseOn the Nose may refer to:*On the Nose , a 2001 film by David Caffrey*"On the Nose" a Price Is Right princing game*"On the Nose", an Australian and New Zealand punting horse race wager...

, Nana, played by Francis Burke refers to an aborigine's head in a large specimen jar as "Oliver Plunkett". - In 2011's musical comedy short film The Holy Ghost of Oliver by Les Doherty and Craig C. Kavanagh, the head of Oliver Plunkett is stolen.

External links

- Cobbett's Complete Collection of State Trials digitised by Google Books

- Biography of St Oliver Plunket

- St Oliver Plunkett webpage maintained by Drogheda Borough Council & St. Peter's Church