Manx language

Encyclopedia

Manx also known as Manx Gaelic, and as the Manks language, is a Goidelic language

of the Indo-European

language family, historically spoken by the Manx people

. Only a small minority of the Island's population is fluent in the language, but a larger minority has some knowledge of it. It is widely considered to be an important part of the Isle of Man's culture and heritage. The last native speaker, Ned Maddrell

, died in 1974. However in recent years the language has been the subject of revival

efforts. Mooinjer Veggey

[muɲdʒer veɣə], a Manx medium playgroup

, was succeeded by the [bʊn-skolʲ ɣɪlɡax], a primary school for 4- to 11-year-olds in St John's. In recent years, despite the small number of speakers, the language has become more visible on the island, with increased signage and radio broadcasts. The revival of Manx has been aided by the fact that the language was well recorded: for example the Bible was translated into Manx, and a number of audio recordings were made of native speakers.

and Scottish Gaelic, use Gaeilge and Gàidhlig respectively for their languages.

To distinguish it from the other two forms of Gaelic, the phrases Gaelg/Gailck Vannin (Gaelic of Mann

) and Gaelg/Gailck Vanninnagh (Manx Gaelic) may also be used.

In addition, the nickname "Çhengey ny Mayrey" (the mother tongue/tongue of the mother) is occasionally used.

, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx) or to avoid confusion with Anglo-Manx

, the form of English as spoken in the Island. Scottish Gaelic is often referred to in English as simply Gaelic, but this is less common with Manx and Irish.

The word Manx is frequently spelled as Manks in historical sources, particularly those written by natives of the island; the word means Mannish, and originates from the Norse Mannisk. The name of the island, Man, is frequently spelled as Mann. It is sometimes accompanied by a footnote explaining that it is a two-syllable word, with the stress on the first syllable, "MAN-en". It comes from the name of the Celtic God "Manannán mac Lir

"

language, closely related to Irish

and Scottish Gaelic. On the whole it is not mutually intelligible with these, though the speakers of the three languages find it easy to gain passive competency in each other's languages and even spoken competency.

Like Scottish Gaelic and modern Irish, Manx is derived from older forms of Irish. The earliest known language of the Isle of Man was a form of Brythonic

.

Manx is descended from Primitive Irish, which is first attested in Ogham

inscriptions from the 4th century AD. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain

. Primitive Irish transitioned into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the 6th century, used the Latin alphabet

and is attested primarily in marginalia

to Latin manuscripts, but there are no extant examples from the Isle of Man. By the 10th century Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland, in Scotland and the Isle of Man. Like the coastal areas of Scotland and Ireland, the Isle of Man was colonised by the Norse, who left their legacy in certain loanwords, personal names, and placenames such as Laxey

(Laksaa) and Ramsay

(Rhumsaa).

During the later Middle Ages, the Isle of Man fell increasingly under the influence of England, and from then on the English language

has been the chief external factor in the development of Manx. Manx began to diverge from Early Modern Irish in around the 13th century and from Scottish Gaelic in the 15th. The language sharply declined during the 19th century and was supplanted by English

.

Manx-language books were not printed until the beginning of the 18th century, and there was no Manx–English dictionary until the 19th century. Except for a few ballads composed in the 16th century and some religious literature, there is no pre-20th century literature in the Manx language. The Manx were to all intents and purposes an oral society, with all folklore, history, interpersonal business and the like passed on by word of mouth.

In 1848, J. G. Cumming wrote that, "there are ... few persons (perhaps none of the young) who speak no English," and Henry Jenner

estimated in 1874 that about 30% of the population habitually spoke Manx (12,340 out of a population of 41,084). According to official census figures, 9.1% of the population claimed to speak Manx in 1901; in 1921 the percentage was only 1.1%. Since the language had fallen to a status of low prestige, parents tended not to teach the language to their children, thinking that Manx would be useless to them compared with English.

Following the decline in the use of Manx during the 19th century, (The Manx Language Society) was founded in 1899. By the middle of the 20th century only a few elderly native speaker

s remained (the last of them, Ned Maddrell

, died on 27 December 1974), but by then a scholarly revival had begun to spread and many people had learned Manx as a second language. The revival of Manx has been aided by the recording work done in the 20th century by researchers. Most notably, the Irish Folklore Commission

was sent in with recording equipment in 1948 by Éamon de Valera

. There is also the work conducted by language enthusiast and fluent speaker Brian Stowell

, who is considered personally responsible for the current revival of the Manx language.

In the 2001 census, 1,689 out of 76,315, or 2.2% of the population, claimed to have knowledge of Manx, although the degree of knowledge varied.

Manx given names are once again becoming common on the Isle of Man, especially Moirrey and Voirrey (Mary, properly pronounced similar to the Scottish Moira, but often mispronounced as Moiree/Voiree when used as a given name by non-Manx speakers), Illiam (William

), Orry (from the Manx King of Norse origin), Breeshey (also Breesha) (Bridget

), Aalish (also Ealish)

(Alice

), Juan (Jack

), Ean (John

), Joney,

Fenella (Fiona

), Pherick (Patrick) and Freya (from the Norse Goddess) remain popular.

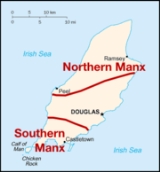

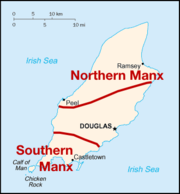

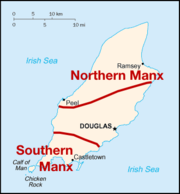

and Scottish Gaelic. It shares a number of developments in phonology, vocabulary and grammar with Irish and Scottish Gaelic (in some cases only with dialects of these), but also shows a number of unique changes. There are two dialects of Manx, Northern Manx and Southern Manx.

Manx shares with Scottish Gaelic the partial loss of contrastive palatalisation of labial consonant

s; thus while in Irish the velarised consonants /pˠ bˠ fˠ w mˠ/ contrast phonemically with palatalised /pʲ bʲ fʲ vʲ mʲ/, in Scottish Gaelic and Manx, the phonemic contrast has been lost to some extent. A consequence of this phonemic merger is that Middle Irish unstressed word-final [əβʲ] (spelled -(a)ibh, -(a)imh in Irish and Gaelic) has merged with [əβ] (-(e)abh, -(e)amh) in Manx; both have become [u], spelled -oo or -u(e). Examples include ("to stand"; Irish ), ("religion"; Irish ), ("fainting"; Early Modern Irish , lit. in clouds), and ("on you (plural)"; Irish ). However, Manx is further advanced in this than is Scottish, where the verb ending -ibh second person plural is consistently [-iv], as it is in the second plural pronoun sibh (shiu in Manx).

Like western and northern dialects of Irish (cf. Irish phonology) and most dialects of Scottish Gaelic, Manx has changed the historical consonant cluster

s /kn ɡn mn tn/ to /kr ɡr mr tr/. For example, Middle Irish ("mockery") and ("women") have become and respectively in Manx. The affrication of [t̪ʲ d̪ʲ] to [tʃ dʒ] is also common to Manx, northern Irish, and Scottish Gaelic.

Also like northern and western dialects of Irish, as well as like southern dialects of Scottish Gaelic (e.g. Arran

, Kintyre

), the unstressed word-final syllable [iʝ] of Middle Irish (spelled -(a)idh and -(a)igh) has developed to [iː] in Manx, where it is spelled -ee, as in ("buy"; cf. Irish ) and ("apparatus"; cf. Gaelic ).

Another property Manx shares with Ulster Irish and some dialects of Scottish Gaelic is that /a/ rather than /ə/ appears in unstressed syllables before /x/ (in Manx spelling, agh), for example ("straight") [ˈdʒiːrax] (Irish ), ("to remember") [ˈkuːnʲaxt̪ən] (Gaelic ).

Similarly to Munster Irish

, historical bh [βʲ] and mh (nasalised [βʲ]) have been lost in the middle or at the end of a word in Manx either with compensatory lengthening

or vocalisation as u resulting in diphthong

isation with the preceding vowel. For example, Manx ("winter") [ˈɡʲeurə], [ˈɡʲuːrə] and ("mountains") [ˈsleːdʒən] correspond to Irish and (Southern Irish dialect spelling and pronunciation gíre ([ˈɟiːɾʲə]) and sléte ([ˈʃlʲeːtʲə])). Another similarity to Munster Irish is the development of the Old Irish diphthongs [oi ai] before velarised consonants (spelled ao in Irish and Scottish Gaelic) to [eː] in many words, as in ("carpenter") [seːr] and ("narrow") [keːl] (spelled and in Irish and Scottish, and pronounced virtually the same in Munster).

Like southern and western varieties of Irish and northern varieties of Scottish Gaelic, but unlike the geographically closer varieties of Ulster Irish

and Arran and Kintyre Gaelic, Manx shows vowel lengthening or diphthongisation before the Old Irish fortis and lenis sonorants. For example, ("children") [klɔːn], ("brown") [d̪ɔːn], ("butter") [iːᵇm] correspond to Irish/Scottish Gaelic , , and respectively, which have long vowels or diphthongs in western and southern Irish and in the Scottish Gaelic dialects of the Outer Hebrides

and Skye

, thus western Irish [klˠɑːn̪ˠ], Southern Irish/Northern Scottish [kl̪ˠaun̪ˠ], [d̪ˠaun̪ˠ]/[d̪ˠoun̪ˠ], [iːm]/[ɤim]), but short vowels and 'long' consonants in northern Irish, Arran, and Kintyre, [kl̪ˠan̪ːˠ], [d̪ˠon̪ːˠ] and [imʲː].

Another similarity with southern Irish is the treatment of Middle Irish word-final unstressed [əð], spelled -(e)adh in Irish and Scottish Gaelic. In nouns (including verbal noun

s), this became [ə] in Manx, as it did in southern Irish, e.g. ("war") [ˈkaːɣə], ("to praise") [ˈmɔlə]; cf. Irish and , pronounced [ˈkˠɔɡˠə] and [ˈmˠɔl̪ˠə] in southern Irish. In finite verb

forms before full nouns (as opposed to pronouns) [əð] became [ax] in Manx, as in southern Irish, e.g. [ˈvɔlax] ("would praise"), cf. Irish , pronounced [ˈvˠɔl̪ˠhəx] in southern Irish.

Linguistic analysis of the last few dozen native speakers reveals a number of dialectal differences between the northern and the southern parts of the island. Northern Manx is reflected by speakers from towns and villages from Maughold

Linguistic analysis of the last few dozen native speakers reveals a number of dialectal differences between the northern and the southern parts of the island. Northern Manx is reflected by speakers from towns and villages from Maughold

in the northeast of the island to Peel on the west coast. Southern Manx is used by speakers from the Sheading of Rushen

.

In Southern Manx, older á and in some cases ó have become [eː]. In Northern Manx the same happens, but á sometimes remains [aː] as well. For example, ("day", cf. Irish ) is [leː] in the south but [leː] or [laː] in the north. Old ó is always [eː] in both dialects, e.g. ("young", cf. Irish ) is [eːɡ] in both dialects.

In Northern Manx, older (e)a before nn in the same syllable is diphthongised, while in Southern Manx it is lengthened but remains a monophthong

. For example, ("head", cf. Irish ) is [kʲaun] in the north but [kʲoːn] in the south.

In both dialects of Manx, words with ua and in some cases ao in Irish and Scottish are spelled with eay in Manx. In Northern Manx, this sound is [iː], while in Southern Manx it is [ɯː], [uː], or [yː]. For example, ("wind", cf. Irish ) is [ɡiː] in the north and [ɡɯː] in the south, while ("coal", cf. Irish is [ɡiːl] in the north and [ɡyːl], [ɡɯːl], or [ɡuːl] in the south.

In both the north and the south, there is a tendency to insert a short [d] sound before a word-final [n] in monosyllabic words, as in [sleᵈn] for ("whole") and [beᵈn] for ("woman"). This phenomenon is known as pre-occlusion

. In Southern Manx, however, there is also pre-occlusion of [d] before [l] and of [ɡ] before [ŋ], as in [ʃuːᵈl] for ("walking") and [lɔᶢŋ] for ("ship"). These forms are generally pronounced without pre-occlusion in the north. Preocclusion of [b] before [m], on the other hand, is more common in the north, as in ("heavy"), which is [t̪roᵇm] in the north but [t̪roːm] or [t̪roːᵇm] in the south. This feature is also found in Cornish

.

Southern Manx tends to lose word-initial [ɡ] before [lʲ], while Northern Manx usually preserves it, e.g. ("glen") is [ɡlʲɔᵈn] in the north and [lʲɔᵈn] in the south, and ("knee") is [ɡlʲuːn] in the north and [lʲuːᵈn] in the south.

is unlike that of Irish and Scottish Gaelic, both of which use closely related modernised variants of the orthography of Early Modern Irish, the language of the educated Gaelic elite of both Ireland and Scotland (where it is called Classical Gaelic

) until the mid-19th century. These orthographies in general show both word pronunciation and word derivation from the Gaelic past, though not in a one-to-one system, there being only 18 letters to represent around 50 phonemes. While Manx in effect uses the English alphabet, except for ⟨x⟩ and ⟨z⟩, the 24 letters of its alphabet likewise do not cover a similar range of phonemes, and therefore many digraphs and trigraphs are used.

The orthography was developed by people who were unaware of traditional Gaelic orthography, as they had learned literacy in Welsh

and English (the initial development in the 16th century), then only English (later developments). Therefore, the orthography shows the pronunciation of words mainly from the point of view of early Modern English "phonetics", and to a small extent Welsh, rather than from the Gaelic point of view. The result is an inconsistent and only partially phonetic spelling system, in the same way that English orthographic practices are inconsistent and only partially phonetic. T. F. O'Rahilly expressed the opinion that Gaelic in the Isle of Man was saddled with a corrupt spelling which is neither traditional nor phonetic; if the traditional Gaelic orthography had been preserved, the close kinship that exists between Manx Gaelic and Scottish Gaelic would be obvious to all at first sight.

There is no evidence of Gaelic script having been used on the island.

s, but a cedilla

is often (but not always) used to differentiate between the two pronunciations of "ch".

, a speaker of Southern Manx.

has been translated into all the Goidelic tongues. Although the wording is not completely cognate, they demonstrate the different orthographies.

" tales and the like were known, with the Manx ballad Fin as Oshin commemorating Finn MacCool and Ossian

. With the coming of Protestantism, this slowly disappeared, while a tradition of carvals, religious songs or carols, developed with religious sanction.

As far as is known, there was no distinctively Manx written literature before the Reformation

, and by this time any presumed literary link with Ireland and Scotland, such as through Irish-trained priests, had been lost. The first published literature in Manx was the Book of Common Prayer

, translated by John Phillips

, the Welsh-born Bishop of Sodor and Man

(1605–33). The early Manx script does have some similarities with orthographical systems found occasionally in Scotland and in Ireland for the transliteration of Gaelic, such as the Book of the Dean of Lismore

, as well as in some cases extensive texts based on English and Scottish English orthographical practices of the time. Little secular Manx literature

has been preserved.

When the Anglican church authorities commenced the production of written literature in the language in the 18th century, the system developed by John Philips was further "anglicized", the one Welsh-retention being the use of ⟨y⟩ to represent schwa (e.g. [kaːβəl] "horse" and [kuːnə] "help" as well as /ɪ/ (e.g. [fɪz] “knowledge”), though it is also used to represent [j], as in English (e.g. [ə juːan] "John" (vocative), [jiːəst] "fish").

Later pieces included short stories and poetry. Translations also occurred, notably of Paradise Lost

in 1796.

In 2006, the first full length novel in Manx, Dunveryssyn yn Tooder-Folley (The Vampire Murders) was published by Brian Stowell, after being serialised in the press.

by the Reverend W. Awdry were written in English, Manx had a significant influence on the world in which they were set. Thomas the Tank Engine

and his fellow locomotive characters live on the fictional Island of Sodor, which is to the east of the Isle of Man, but at the same time loosely based on it. It has its own language "Sudric", which "is fast dying out and is akin to Manx and Gaelic" – but the difference between Manx and Sudric is not enough to prevent the two communities understanding one another.

A lot of the names, are clearly based on Manx forms, but often the nouns are inverted to match English word order. Some of the locations have quasi-Manx names, e.g. Killdane, which comes from "Keeill-y-Deighan" (Church of the Devil), hills are called Knock and Cronk, while "Nagh Beurla", means "I speak no English", a distortion of the Manx. The names of some of the 'historical' characters – used in the background but not appearing in the stories – were taken from locations on the Isle of Man, such as Sir Crosby Marown (Crosby

being a small village in the parish of Marown) and Harold Regaby.

The voiceless plosives are pronounced with aspiration

. The dental, postalveolar and palato-velar plosives /t̪ d̪ tʲ dʲ kʲ/ are affricated to [t̪͡θ d̪͡ð t͡ʃ d͡ʒ kʲ͡ç] in many contexts.

Manx has an optional process of lenition

of plosives between vowels, whereby voiced plosives and voiceless fricatives become voiced fricatives and voiceless plosives become either voiced plosives or voiced fricatives. This process introduces the allophone

s [β ð z ʒ] to the series of voiced fricatives in Manx. The voiced fricative [ʒ] may be further lenited to [j], and [ɣ] may disappear altogether. Examples include:

Voiceless plosive to voiced plosive → [d̪]: [ˈbrad̪aɡ] "flag, rag" → [ɡ]: [ˈpɛɡə] "sin"

Voiceless plosive to voiced fricative → [v]: [ˈkavan] "cup" → [ð]: [ˈbɛːða] "boat" → [ɣ]: [ˈfiːɣəl] "tooth"

Voiced plosive to voiced fricative → [v]: [ˈkaːvəl] "horse" → [ð]: [ˈɛðənʲ] "face" → [ʒ]: [ˈpaːʒər] "prayer" → [ʒ] → [j]: [ˈmaːʒə], [ˈmaːjə] "stick" → [ɣ]: [ˈroɣət] "born"

Voiceless fricative to voiced fricative → [ð] or [z]: [ˈpuːðitʲ] or [ˈpuːzitʲ] "married" → [ð]: [ˈʃaːðu] "stand" → [ʒ]: [ˈɛːʒax] "easy" → [ʒ] → [j]: [ˈt̪ɔʒax], [ˈt̪ɔjax] "beginning" → [ɣ]: [ˈbɛːɣə] "live" → [ɣ] → : [ʃaː] "past"

Another optional process of Manx phonology is pre-occlusion

, the insertion of a very short plosive consonant before a sonorant consonant. In Manx, this applies to stressed monosyllabic words (i.e. words one syllable long). The inserted consonant is homorganic with the following sonorant, which means it has the same place of articulation

. Long vowels are often shortened before pre-occluded sounds. Examples include: → [ᵇm]: /t̪roːm/ → [t̪roᵇm] "heavy" → [ᵈn]: /kʲoːn/ → [kʲoᵈn] "head" → [ᵈnʲ]: /eːnʲ/ → [eːᵈnʲ], [eᵈnʲ] "birds" → [ᶢŋ]: /loŋ/ → [loᶢŋ] "ship" → [ᵈl]: /ʃuːl/ → [ʃuːᵈl] "walking"

The trill /r/ is realised as a one- or two-contact flap [ɾ] at the beginning of syllable, and as a stronger trill [r] when preceded by another consonant in the same syllable. At the end of a syllable, /r/ can be pronounced either as a strong trill [r] or, more frequently, as a weak fricative [ɹ̝], which may vocalise to a nonsyllabic [ə̯] or disappear altogether. This vocalisation may be due to the influence of Manx English

, which is itself a non-rhotic accent. Examples of the pronunciation of /r/ include: "snare" [ˈɾibə] "bread" [ˈaɾan] "big" [muːr], [muːɹ̝], [muːə̯], [muː]

The status of æ and æː as separate phonemes is debatable, but is suggested by the allophony of certain words such as "is", "women", and so on. An alternative analysis is that Manx has the following system, where the vowels /a/ and /aː/ have allophones ranging from [ɛ]/[ɛː] through [æ]/[æː] to [a]/[aː]. As with Irish and Scottish Gaelic, there is a large amount of vowel allophony, such as that of /a/,/a:/. This depends mainly on the 'broad' and 'slender' status of the neighbouring consonants:

When stressed, /ə/ is realised as [ø].

Manx has a relatively large number of diphthong

s, all of them falling:

, masculine or feminine. Nouns are inflected for number

(the plural

being formed in a variety of ways, most commonly by addition of the suffix -yn [ən]), but usually there is no inflection for case

, except in a minority of nouns that have a distinct genitive singular form, which is formed in various ways (most common is the addition of the suffix -ey [ə] to feminine nouns). Historical genitive singulars are often encountered in compound

s even when they are no longer productive

forms; for example "cowhouse" uses the old genitive of "cattle".

Manx verbs generally form their finite

forms by means of periphrasis

: inflected forms of the auxiliary verb

s "to be" or "to do" are combined with the verbal noun

of the main verb. Only the future

, conditional, preterite

, and imperative

can be formed directly by inflecting the main verb, but even in these tenses, the periphrastic formation is more common in Late Spoken Manx. Examples:

The future and conditional tenses (and in some irregular verb

s, the preterite) make a distinction between "independent" and "dependent" forms

. Independent forms are used when the verb is not preceded by any particle; dependent forms are used when a particle (e.g. "not") does precede the verb. For example, "you will lose" is with the independent form ("will lose"), while "you will not lose" is with the dependent form (which has undergone eclipsis to after ). Similarly "they went" is with the independent form ("went"), while "they did not go" is with the dependent form . This contrast is inherited from Old Irish, which shows such pairs as ("(s)he carries") vs. ("(s)he does not carry"), and is found in Scottish Gaelic as well, e.g. ("will take") vs. ("will not take"). In Modern Irish, the distinction is found only in irregular verbs (e.g. ("saw") vs. ("did not see").

Like the other Insular Celtic languages

, Manx has so-called inflected preposition

s, contractions of a preposition with a pronominal

direct object. For example, the preposition "at" has the following forms:

and/or syntactic

environment. Manx has two mutations: lenition

and nasalisation, found on nouns and verbs in a variety of environments; adjectives can undergo lenition but not nasalisation. In the late spoken language of the 20th century the system was breaking down, with speakers frequently failing to use mutation in environments where it was called for, and occasionally using it in environments where it was not called for.

, which itself precedes the direct object. However, as noted above, most finite verbs are formed periphrastically, using an auxiliary verb in conjunction with the verbal noun. In this case, only the auxiliary verb precedes the subject, while the verbal noun comes after the subject. The auxiliary verb may be a modal verb

rather than a form of ("be") or ("do"). Particles like the negative ("not") precede the inflected verb. Examples:

verb}}

| colspan=2 |

| colspan=2 |

|-

| || || || || ||

|-

| put- || the || priest || his || hand || on her

|-

| colspan=6 | "The priest put his hand on her."

|}

Goidelic languages

The Goidelic languages or Gaelic languages are one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic languages, the other consisting of the Brythonic languages. Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from the south of Ireland through the Isle of Man to the north of Scotland...

of the Indo-European

Indo-European

Indo-European may refer to:* Indo-European languages** Aryan race, a 19th century and early 20th century term for those peoples who are the native speakers of Indo-European languages...

language family, historically spoken by the Manx people

Manx people

The Manx are an ethnic group coming from the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea in northern Europe. They are often described as a Celtic people, though they have had a mixed background including Norse and English influences....

. Only a small minority of the Island's population is fluent in the language, but a larger minority has some knowledge of it. It is widely considered to be an important part of the Isle of Man's culture and heritage. The last native speaker, Ned Maddrell

Ned Maddrell

Edward "Ned" Maddrell was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the Manx language.Following the death of Mrs. Sage Kinvig Edward "Ned" Maddrell (1877 – December 27, 1974) was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the...

, died in 1974. However in recent years the language has been the subject of revival

Language revival

Language revitalization, language revival or reversing language shift is the attempt by interested parties, including individuals, cultural or community groups, governments, or political authorities, to reverse the decline of a language. If the decline is severe, the language may be endangered,...

efforts. Mooinjer Veggey

Mooinjer veggey

is the Manx for little people, a term used for fairies in Gaelic lore. The equivalent Irish is Muintir Bheaga.-Manx folklore:In Manx folklore, the are small creatures from two to three feet in height, otherwise very like mortals. They wear red caps and green jackets and are most often seen on...

[muɲdʒer veɣə], a Manx medium playgroup

Playgroup

Playgroup may refer to:* Pre-school playgroup, a kind of pre-school care*Playgroup , a British dance act*Playgroup , arts and entertainment events in England...

, was succeeded by the [bʊn-skolʲ ɣɪlɡax], a primary school for 4- to 11-year-olds in St John's. In recent years, despite the small number of speakers, the language has become more visible on the island, with increased signage and radio broadcasts. The revival of Manx has been aided by the fact that the language was well recorded: for example the Bible was translated into Manx, and a number of audio recordings were made of native speakers.

Manx

In Manx the language is called Gaelg or Gailck, a word which shares the same etymological root as the English word "Gaelic". The two sister languages of Manx, IrishIrish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

and Scottish Gaelic, use Gaeilge and Gàidhlig respectively for their languages.

To distinguish it from the other two forms of Gaelic, the phrases Gaelg/Gailck Vannin (Gaelic of Mann

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man , otherwise known simply as Mann , is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, located in the Irish Sea between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, within the British Isles. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann. The Lord of Mann is...

) and Gaelg/Gailck Vanninnagh (Manx Gaelic) may also be used.

In addition, the nickname "Çhengey ny Mayrey" (the mother tongue/tongue of the mother) is occasionally used.

English

The language is usually referred to in English as Manx. The term Manx Gaelic is also often used, for example when discussing the relationship between the three Goidelic languages (IrishIrish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx) or to avoid confusion with Anglo-Manx

Manx English

Manx English, or Anglo-Manx, is the historic dialect of English spoken on the Isle of Man, though today in decline. It has many borrowings from the original Manx language, a Goidelic language, and it differs widely from any other English, including other Celtic-derived dialects such as Welsh...

, the form of English as spoken in the Island. Scottish Gaelic is often referred to in English as simply Gaelic, but this is less common with Manx and Irish.

The word Manx is frequently spelled as Manks in historical sources, particularly those written by natives of the island; the word means Mannish, and originates from the Norse Mannisk. The name of the island, Man, is frequently spelled as Mann. It is sometimes accompanied by a footnote explaining that it is a two-syllable word, with the stress on the first syllable, "MAN-en". It comes from the name of the Celtic God "Manannán mac Lir

Manannán mac Lir

Manannán mac Lir is a sea deity in Irish mythology. He is the son of the obscure Lir . He is often seen as a psychopomp, and has strong affiliations with the Otherworld, the weather and the mists between the worlds...

"

History

Manx is a GoidelicGoidelic languages

The Goidelic languages or Gaelic languages are one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic languages, the other consisting of the Brythonic languages. Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from the south of Ireland through the Isle of Man to the north of Scotland...

language, closely related to Irish

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

and Scottish Gaelic. On the whole it is not mutually intelligible with these, though the speakers of the three languages find it easy to gain passive competency in each other's languages and even spoken competency.

Like Scottish Gaelic and modern Irish, Manx is derived from older forms of Irish. The earliest known language of the Isle of Man was a form of Brythonic

British language

The British language was an ancient Celtic language spoken in Britain.British language may also refer to:* Any of the Languages of the United Kingdom.*The Welsh language or the Brythonic languages more generally* British English...

.

Manx is descended from Primitive Irish, which is first attested in Ogham

Ogham

Ogham is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the Old Irish language, and occasionally the Brythonic language. Ogham is sometimes called the "Celtic Tree Alphabet", based on a High Medieval Bríatharogam tradition ascribing names of trees to the individual letters.There are roughly...

inscriptions from the 4th century AD. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

. Primitive Irish transitioned into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the 6th century, used the Latin alphabet

Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet, also called the Roman alphabet, is the most recognized alphabet used in the world today. It evolved from a western variety of the Greek alphabet called the Cumaean alphabet, which was adopted and modified by the Etruscans who ruled early Rome...

and is attested primarily in marginalia

Marginalia

Marginalia are scribbles, comments, and illuminations in the margins of a book.- Biblical manuscripts :Biblical manuscripts have liturgical notes at the margin, for liturgical use. Numbers of texts' divisions are given at the margin...

to Latin manuscripts, but there are no extant examples from the Isle of Man. By the 10th century Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland, in Scotland and the Isle of Man. Like the coastal areas of Scotland and Ireland, the Isle of Man was colonised by the Norse, who left their legacy in certain loanwords, personal names, and placenames such as Laxey

Laxey

Laxey is a village on the east coast of the Isle of Man. Its name derives from the Old Norse Laxa meaning 'Salmon River'.The village lies on the A2, the main Douglas to Ramsey road. Laxey Glen is one of the Manx National Glens, with Dhoon Glen being located close by...

(Laksaa) and Ramsay

Ramsey, Isle of Man

Ramsey is a town in the north of the Isle of Man. It is the second largest town on the island after Douglas. Its population is 7,309 according to the 2006 census . It has one of the biggest harbours on the island, and has a prominent derelict pier, called the Queen's Pier. It was formerly one of...

(Rhumsaa).

During the later Middle Ages, the Isle of Man fell increasingly under the influence of England, and from then on the English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

has been the chief external factor in the development of Manx. Manx began to diverge from Early Modern Irish in around the 13th century and from Scottish Gaelic in the 15th. The language sharply declined during the 19th century and was supplanted by English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

.

Manx-language books were not printed until the beginning of the 18th century, and there was no Manx–English dictionary until the 19th century. Except for a few ballads composed in the 16th century and some religious literature, there is no pre-20th century literature in the Manx language. The Manx were to all intents and purposes an oral society, with all folklore, history, interpersonal business and the like passed on by word of mouth.

In 1848, J. G. Cumming wrote that, "there are ... few persons (perhaps none of the young) who speak no English," and Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner FSA was a British scholar of the Celtic languages, a Cornish cultural activist, and the chief originator of the Cornish language revival....

estimated in 1874 that about 30% of the population habitually spoke Manx (12,340 out of a population of 41,084). According to official census figures, 9.1% of the population claimed to speak Manx in 1901; in 1921 the percentage was only 1.1%. Since the language had fallen to a status of low prestige, parents tended not to teach the language to their children, thinking that Manx would be useless to them compared with English.

Following the decline in the use of Manx during the 19th century, (The Manx Language Society) was founded in 1899. By the middle of the 20th century only a few elderly native speaker

Native Speaker

Native Speaker is Chang-Rae Lee’s first novel. In Native Speaker, he creates a man named Henry Park who tries to assimilate into American society and become a “native speaker.”-Plot summary:...

s remained (the last of them, Ned Maddrell

Ned Maddrell

Edward "Ned" Maddrell was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the Manx language.Following the death of Mrs. Sage Kinvig Edward "Ned" Maddrell (1877 – December 27, 1974) was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the...

, died on 27 December 1974), but by then a scholarly revival had begun to spread and many people had learned Manx as a second language. The revival of Manx has been aided by the recording work done in the 20th century by researchers. Most notably, the Irish Folklore Commission

Irish Folklore Commission

The Irish Folklore Commission was set up in 1935 by the Irish Government to study and collect information on the folklore and traditions of Ireland....

was sent in with recording equipment in 1948 by Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

. There is also the work conducted by language enthusiast and fluent speaker Brian Stowell

Brian Stowell

Brian Stowell is a Manx radio personality, linguist and author. He is considered one of the primary people behind the revival of the Manx language. While a student he became fluent in the language, and made tape recordings of its elderly speakers. He became fluent in Irish and used his fluency to...

, who is considered personally responsible for the current revival of the Manx language.

In the 2001 census, 1,689 out of 76,315, or 2.2% of the population, claimed to have knowledge of Manx, although the degree of knowledge varied.

Manx given names are once again becoming common on the Isle of Man, especially Moirrey and Voirrey (Mary, properly pronounced similar to the Scottish Moira, but often mispronounced as Moiree/Voiree when used as a given name by non-Manx speakers), Illiam (William

William (name)

William is a popular given name of old Germanic origin. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era...

), Orry (from the Manx King of Norse origin), Breeshey (also Breesha) (Bridget

Bridget (given name)

Bridget or Brigid is a Celtic/Irish female name derived from the noun brígh, meaning "power, strength, vigor, virtue." An alternate meaning of the name is "exalted one"...

), Aalish (also Ealish)

(Alice

Alice (given name)

Alice is a feminine given name used primarily in English, French, and Italian. It is a shortened form of the Old French Adelais, which is derivation from the Germanic name Adalheidis, from the Germanic word elements adal, meaning noble and heid, meaning type...

), Juan (Jack

Jack (name)

Jack is a male given name, although in very rare cases it can be used as a female given name, and sometimes as a surname.In English it is traditionally used as the diminutive form of the name John, though it is also often given as a proper name in its own right.The name Jack is unique in the...

), Ean (John

John (name)

John is a masculine given name in the English language. The name is derived from the Latin Ioannes, Iohannes, which is in turn a form of the Greek , Iōánnēs. This Greek name is a form of the Hebrew name , , which means "God is generous"...

), Joney,

Fenella (Fiona

Fiona

Fiona is a feminine given name. The name Fiona was invented, and first used, by the Scottish poet James Macpherson , author of the Ossian poems, which he claimed were translations from ancient Gaelic sources...

), Pherick (Patrick) and Freya (from the Norse Goddess) remain popular.

Classification and dialects

Manx is one of the three descendants of Old Irish (via Middle Irish and early Modern Gaelic), and is closely related to IrishIrish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

and Scottish Gaelic. It shares a number of developments in phonology, vocabulary and grammar with Irish and Scottish Gaelic (in some cases only with dialects of these), but also shows a number of unique changes. There are two dialects of Manx, Northern Manx and Southern Manx.

Manx shares with Scottish Gaelic the partial loss of contrastive palatalisation of labial consonant

Labial consonant

Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. This precludes linguolabials, in which the tip of the tongue reaches for the posterior side of the upper lip and which are considered coronals...

s; thus while in Irish the velarised consonants /pˠ bˠ fˠ w mˠ/ contrast phonemically with palatalised /pʲ bʲ fʲ vʲ mʲ/, in Scottish Gaelic and Manx, the phonemic contrast has been lost to some extent. A consequence of this phonemic merger is that Middle Irish unstressed word-final [əβʲ] (spelled -(a)ibh, -(a)imh in Irish and Gaelic) has merged with [əβ] (-(e)abh, -(e)amh) in Manx; both have become [u], spelled -oo or -u(e). Examples include ("to stand"; Irish ), ("religion"; Irish ), ("fainting"; Early Modern Irish , lit. in clouds), and ("on you (plural)"; Irish ). However, Manx is further advanced in this than is Scottish, where the verb ending -ibh second person plural is consistently [-iv], as it is in the second plural pronoun sibh (shiu in Manx).

Like western and northern dialects of Irish (cf. Irish phonology) and most dialects of Scottish Gaelic, Manx has changed the historical consonant cluster

Consonant cluster

In linguistics, a consonant cluster is a group of consonants which have no intervening vowel. In English, for example, the groups and are consonant clusters in the word splits....

s /kn ɡn mn tn/ to /kr ɡr mr tr/. For example, Middle Irish ("mockery") and ("women") have become and respectively in Manx. The affrication of [t̪ʲ d̪ʲ] to [tʃ dʒ] is also common to Manx, northern Irish, and Scottish Gaelic.

Also like northern and western dialects of Irish, as well as like southern dialects of Scottish Gaelic (e.g. Arran

Isle of Arran

Arran or the Isle of Arran is the largest island in the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, and with an area of is the seventh largest Scottish island. It is in the unitary council area of North Ayrshire and the 2001 census had a resident population of 5,058...

, Kintyre

Kintyre

Kintyre is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The region stretches approximately 30 miles , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south, to East Loch Tarbert in the north...

), the unstressed word-final syllable [iʝ] of Middle Irish (spelled -(a)idh and -(a)igh) has developed to [iː] in Manx, where it is spelled -ee, as in ("buy"; cf. Irish ) and ("apparatus"; cf. Gaelic ).

Another property Manx shares with Ulster Irish and some dialects of Scottish Gaelic is that /a/ rather than /ə/ appears in unstressed syllables before /x/ (in Manx spelling, agh), for example ("straight") [ˈdʒiːrax] (Irish ), ("to remember") [ˈkuːnʲaxt̪ən] (Gaelic ).

Similarly to Munster Irish

Munster Irish

Munster Irish is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Munster. Gaeltacht regions in Munster are found in the Dingle Peninsula Gaeltacht of west Kerry, in the Iveragh Peninsula in south Kerry, in Cape Clear Island off the coast of west Cork, in West Muskerry; Coolea,...

, historical bh [βʲ] and mh (nasalised [βʲ]) have been lost in the middle or at the end of a word in Manx either with compensatory lengthening

Compensatory lengthening

Compensatory lengthening in phonology and historical linguistics is the lengthening of a vowel sound that happens upon the loss of a following consonant, usually in the syllable coda...

or vocalisation as u resulting in diphthong

Diphthong

A diphthong , also known as a gliding vowel, refers to two adjacent vowel sounds occurring within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: That is, the tongue moves during the pronunciation of the vowel...

isation with the preceding vowel. For example, Manx ("winter") [ˈɡʲeurə], [ˈɡʲuːrə] and ("mountains") [ˈsleːdʒən] correspond to Irish and (Southern Irish dialect spelling and pronunciation gíre ([ˈɟiːɾʲə]) and sléte ([ˈʃlʲeːtʲə])). Another similarity to Munster Irish is the development of the Old Irish diphthongs [oi ai] before velarised consonants (spelled ao in Irish and Scottish Gaelic) to [eː] in many words, as in ("carpenter") [seːr] and ("narrow") [keːl] (spelled and in Irish and Scottish, and pronounced virtually the same in Munster).

Like southern and western varieties of Irish and northern varieties of Scottish Gaelic, but unlike the geographically closer varieties of Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish

Ulster Irish is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the Province of Ulster. The largest Gaeltacht region today is in County Donegal, so that the term Donegal Irish is often used synonymously. Nevertheless, records of the language as it was spoken in other counties do exist, and help provide...

and Arran and Kintyre Gaelic, Manx shows vowel lengthening or diphthongisation before the Old Irish fortis and lenis sonorants. For example, ("children") [klɔːn], ("brown") [d̪ɔːn], ("butter") [iːᵇm] correspond to Irish/Scottish Gaelic , , and respectively, which have long vowels or diphthongs in western and southern Irish and in the Scottish Gaelic dialects of the Outer Hebrides

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

and Skye

Skye

Skye or the Isle of Skye is the largest and most northerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin hills...

, thus western Irish [klˠɑːn̪ˠ], Southern Irish/Northern Scottish [kl̪ˠaun̪ˠ], [d̪ˠaun̪ˠ]/[d̪ˠoun̪ˠ], [iːm]/[ɤim]), but short vowels and 'long' consonants in northern Irish, Arran, and Kintyre, [kl̪ˠan̪ːˠ], [d̪ˠon̪ːˠ] and [imʲː].

Another similarity with southern Irish is the treatment of Middle Irish word-final unstressed [əð], spelled -(e)adh in Irish and Scottish Gaelic. In nouns (including verbal noun

Verbal noun

In linguistics, the verbal noun turns a verb into a noun and corresponds to the infinitive in English language usage. In English the infinitive form of the verb is formed when preceded by to, e.g...

s), this became [ə] in Manx, as it did in southern Irish, e.g. ("war") [ˈkaːɣə], ("to praise") [ˈmɔlə]; cf. Irish and , pronounced [ˈkˠɔɡˠə] and [ˈmˠɔl̪ˠə] in southern Irish. In finite verb

Finite verb

A finite verb is a verb that is inflected for person and for tense according to the rules and categories of the languages in which it occurs. Finite verbs can form independent clauses, which can stand on their own as complete sentences....

forms before full nouns (as opposed to pronouns) [əð] became [ax] in Manx, as in southern Irish, e.g. [ˈvɔlax] ("would praise"), cf. Irish , pronounced [ˈvˠɔl̪ˠhəx] in southern Irish.

Maughold

Saint Maughold of Man is venerated as the patron saint of the Isle of Man...

in the northeast of the island to Peel on the west coast. Southern Manx is used by speakers from the Sheading of Rushen

Rushen

Rushen , formerly Kirk Christ Rushen , is a parish in the sheading of the same name in the Isle of Man. The parish is a fishing and agricultural district at the south-westernmost point of the island. The parish is one of three in the sheading of Rushen...

.

In Southern Manx, older á and in some cases ó have become [eː]. In Northern Manx the same happens, but á sometimes remains [aː] as well. For example, ("day", cf. Irish ) is [leː] in the south but [leː] or [laː] in the north. Old ó is always [eː] in both dialects, e.g. ("young", cf. Irish ) is [eːɡ] in both dialects.

In Northern Manx, older (e)a before nn in the same syllable is diphthongised, while in Southern Manx it is lengthened but remains a monophthong

Monophthong

A monophthong is a pure vowel sound, one whose articulation at both beginning and end is relatively fixed, and which does not glide up or down towards a new position of articulation....

. For example, ("head", cf. Irish ) is [kʲaun] in the north but [kʲoːn] in the south.

In both dialects of Manx, words with ua and in some cases ao in Irish and Scottish are spelled with eay in Manx. In Northern Manx, this sound is [iː], while in Southern Manx it is [ɯː], [uː], or [yː]. For example, ("wind", cf. Irish ) is [ɡiː] in the north and [ɡɯː] in the south, while ("coal", cf. Irish is [ɡiːl] in the north and [ɡyːl], [ɡɯːl], or [ɡuːl] in the south.

In both the north and the south, there is a tendency to insert a short [d] sound before a word-final [n] in monosyllabic words, as in [sleᵈn] for ("whole") and [beᵈn] for ("woman"). This phenomenon is known as pre-occlusion

Pre-occlusion

Pre-occlusion is a phonological process, involving the insertion of a very short plosive consonant before a sonorant consonant. In Manx, this applies to stressed monosyllabic words , and is also found in Cornish on certain stressed syllables. The inserted consonant is homorganic with the following...

. In Southern Manx, however, there is also pre-occlusion of [d] before [l] and of [ɡ] before [ŋ], as in [ʃuːᵈl] for ("walking") and [lɔᶢŋ] for ("ship"). These forms are generally pronounced without pre-occlusion in the north. Preocclusion of [b] before [m], on the other hand, is more common in the north, as in ("heavy"), which is [t̪roᵇm] in the north but [t̪roːm] or [t̪roːᵇm] in the south. This feature is also found in Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

.

Southern Manx tends to lose word-initial [ɡ] before [lʲ], while Northern Manx usually preserves it, e.g. ("glen") is [ɡlʲɔᵈn] in the north and [lʲɔᵈn] in the south, and ("knee") is [ɡlʲuːn] in the north and [lʲuːᵈn] in the south.

Orthography

The Manx orthographyOrthography

The orthography of a language specifies a standardized way of using a specific writing system to write the language. Where more than one writing system is used for a language, for example Kurdish, Uyghur, Serbian or Inuktitut, there can be more than one orthography...

is unlike that of Irish and Scottish Gaelic, both of which use closely related modernised variants of the orthography of Early Modern Irish, the language of the educated Gaelic elite of both Ireland and Scotland (where it is called Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic

Classical Gaelic is the term used in Scotland for the shared literary form that was in use in Scotland and Ireland 13th to the 18th century. The language is that of Early Modern Irish...

) until the mid-19th century. These orthographies in general show both word pronunciation and word derivation from the Gaelic past, though not in a one-to-one system, there being only 18 letters to represent around 50 phonemes. While Manx in effect uses the English alphabet, except for ⟨x⟩ and ⟨z⟩, the 24 letters of its alphabet likewise do not cover a similar range of phonemes, and therefore many digraphs and trigraphs are used.

The orthography was developed by people who were unaware of traditional Gaelic orthography, as they had learned literacy in Welsh

Welsh language

Welsh is a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages spoken natively in Wales, by some along the Welsh border in England, and in Y Wladfa...

and English (the initial development in the 16th century), then only English (later developments). Therefore, the orthography shows the pronunciation of words mainly from the point of view of early Modern English "phonetics", and to a small extent Welsh, rather than from the Gaelic point of view. The result is an inconsistent and only partially phonetic spelling system, in the same way that English orthographic practices are inconsistent and only partially phonetic. T. F. O'Rahilly expressed the opinion that Gaelic in the Isle of Man was saddled with a corrupt spelling which is neither traditional nor phonetic; if the traditional Gaelic orthography had been preserved, the close kinship that exists between Manx Gaelic and Scottish Gaelic would be obvious to all at first sight.

There is no evidence of Gaelic script having been used on the island.

Cedilla

Manx uses relatively few diacriticDiacritic

A diacritic is a glyph added to a letter, or basic glyph. The term derives from the Greek διακριτικός . Diacritic is both an adjective and a noun, whereas diacritical is only an adjective. Some diacritical marks, such as the acute and grave are often called accents...

s, but a cedilla

Cedilla

A cedilla , also known as cedilha or cédille, is a hook added under certain letters as a diacritical mark to modify their pronunciation.-Origin:...

is often (but not always) used to differentiate between the two pronunciations of "ch".

- Çhiarn (ˈtʃaːrn) means "lord" and is pronounced with a hard "ch" (/tʃ/) as in the English "watch"

- Cha means "not", and is pronounced with a velar fricativeVoiceless velar fricativeThe voiceless velar fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The sound was part of the consonant inventory of Old English and can still be found in some dialects of English, most notably in Scottish English....

, as in the correct pronunciation of the Scots "loch" (/ˈlɒx/ ), a sound which is more commonly represented by "gh" in Manx. This is one of the features Manx shares with the Northern dialects of Irish and Scottish Gaelic (instead of the negation ní used elsewhere in Ireland).

Examples

The following examples are taken from Broderick 1984–86, 1:178–79 and 1:350–53. The first example is from a speaker of Northern Manx, the second from Ned MaddrellNed Maddrell

Edward "Ned" Maddrell was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the Manx language.Following the death of Mrs. Sage Kinvig Edward "Ned" Maddrell (1877 – December 27, 1974) was a fisherman from the Isle of Man who was the last surviving native speaker of the...

, a speaker of Southern Manx.

| Orthography | Phonetic transcription | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| vod̪ ˈsmuːnʲaxt̪ən d̪ə biəx ˈkaːbəl dʒiːən skiː as ˈd̪øinʲax uns ə ˈvoːxəri d̪ə biəx e er vi ek nə ˈferiʃən fod̪ nə høi as biəx əd̪ kør leʃ ən ˈsaːɡərt̪ d̪ə kør ə ˈvanax er | They used to think if a horse was looking tired and weary in the morning then it had been with the fairies all night and they would bring the priest to put his blessing on it. | |

| və ˈbɛn əˈsoː ən ˈtʃaːn ˈkai as vai ˈlaːl ˈmiʃ ði ˈjinðax i ðə ˈɡreː in ˈpaːdʒər ən ˈtʃaːrn ‖ d̪ot̪ i ðə ˈrau i ɡreː a ˈt̪reː vai iˈnʲin ˈveːɡ ‖ ax t̪e ˈolʲu dʒaˈrud̪ətʃ ek ‖ as vei ˈlaːl ˈɡʲinðax a ˈriːʃ san ðə ˈɡreː ə əɡ ˈvraːst̪əl nə ˈrið ənax ‖ as ˈd̪ut̪ miʃ ðə ˈdʒinax mi ˈdʒinu mə ˈʃeː san ðə ˈkunə lʲei as ˈrenʲ i ˈtʃit̪ oˈsoː san ðə ˈklaːʃtʲən a ‖ as vel u ˈlaːl ðə ˈklaːʃtʲən mi ðə ˈɡreː a ‖ | There was a woman here last week and she wanted me to teach her to say the Lord's Prayer. She said that she used to say it when she was a little girl, but she has forgotten it all, and she wanted to learn it again to say it at a class or something. And I said I would do my best to help her and she came here to hear it, and do you want to hear me say it? |

Gaelic versions of the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's PrayerLord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer is a central prayer in Christianity. In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, it appears in two forms: in the Gospel of Matthew as part of the discourse on ostentation in the Sermon on the Mount, and in the Gospel of Luke, which records Jesus being approached by "one of his...

has been translated into all the Goidelic tongues. Although the wording is not completely cognate, they demonstrate the different orthographies.

- The standard version of the Lord's Prayer in Manx

- Ayr ain t'ayns niau,

- Casherick dy row dt'ennym.

- Dy jig dty reeriaght.

- Dt'aigney dy row jeant er y thalloo,

- myr t'ayns niau.

- Cur dooin nyn arran jiu as gagh laa,

- as leih dooin nyn loghtyn,

- myr ta shin leih dauesyn ta jannoo loghtyn nyn 'oi.

- As ny leeid shin ayns miolagh,

- agh livrey shin veih olk:

- Son lhiats y reeriaght, as y phooar, as y ghloyr, son dy bragh as dy bragh.

- Amen.

- Manx version of 1713

- Ayr Ain, t'ayns Niau;

- Caſherick dy rou dt'ennym;

- Di jig dty Reereeaght;

- Dt'aigney dy rou jeant er y Talloo

- myr t'ayns Niau;

- Cur dooin nyn Arran jiu as gagh laa;

- As leih dooin nyn Loghtyn,

- myr ta ſhin leih daueſyn ta janoo loghtyn ny noi ſhin;

- As ny leeid ſhin ayns Miolagh;

- Agh livrey ſhin veih olk;

- Son liats y Reeriaght y Phooar as y Ghloyr, ſon dy bragh as dy bragh.

- Amen

- The prayer in Old Irish

- A athair fil hi nimib,

- Noemthar thainm.

- Tost do flaithius.

- Did do toil i talmain

- amail ata in nim.

- Tabair dun indiu ar sasad lathi.

- Ocus log dun ar fiachu

- amail logmaitne diar fhechemnaib.

- Ocus nis lecea sind i n-amus n-dofulachtai.

- Acht ron soer o cech ulc.

- Amen ropfir.

- The Prayer in modern Irish

- Ár n-Athair, atá ar neamh:

- go naofar d'ainm (alt. go naomhaíthear t'ainm).

- Go dtaga do ríocht (alt.go dtagaidh do ríocht).

- Go ndéantar do thoil ar an talamh (alt. ar an dtalamh),

- mar dhéantar ar neamh.

- Ár n-arán laethúil tabhair dúinn inniu,

- agus maith dúinn ár bhfiacha (alt. ár gcionta),

- mar mhaithimid dár bhféichiúna féin (alt. mar a mhaithimíd dóibh a chiontaíonn inár n-aghaidh).

- Agus ná lig sinn i gcathú (alt. i gcathaíbh),

- ach saor sinn ó olc (alt. ón olc).

- Óir is leatsa an Ríocht agus an Chumhacht agus an Ghloir, tré shaol na saol (alt. le saol na saol / go síoraí).

- Amen (alt. Âiméin).

- The Prayer in Scottish Gaelic

- Ar n-Athair a tha air nèamh,

- Gu naomhaichear d' ainm.

- Thigeadh do rìoghachd.

- Dèanar do thoil air an talamh,

- mar a nithear air nèamh.

- Tabhair dhuinn an-diugh ar n-aran làitheil.

- Agus maith dhuinn ar fiachan,

- amhail a mhaitheas sinne dar luchd-fiach.

- Agus na leig ann am buaireadh sinn;

- ach saor sinn o olc:

- oir is leatsa an rìoghachd, agus a' chumhachd, agus a' ghlòir, gu sìorraidh.

- Amen.

Literature

Because Manx has never had a large user base, it has never been practical to produce large amounts of written literature. A body of oral literature, on the other hand, did exist. It is known that the "FiannaFianna

Fianna were small, semi-independent warrior bands in Irish mythology and Scottish mythology, most notably in the stories of the Fenian Cycle, where they are led by Fionn mac Cumhaill....

" tales and the like were known, with the Manx ballad Fin as Oshin commemorating Finn MacCool and Ossian

Ossian

Ossian is the narrator and supposed author of a cycle of poems which the Scottish poet James Macpherson claimed to have translated from ancient sources in the Scots Gaelic. He is based on Oisín, son of Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill, anglicised to Finn McCool, a character from Irish mythology...

. With the coming of Protestantism, this slowly disappeared, while a tradition of carvals, religious songs or carols, developed with religious sanction.

As far as is known, there was no distinctively Manx written literature before the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, and by this time any presumed literary link with Ireland and Scotland, such as through Irish-trained priests, had been lost. The first published literature in Manx was the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

, translated by John Phillips

John Philips (bishop)

John Phillips was the Anglican Bishop of Sodor and Man between 1604/5 and 1633. His most notable contribution to society was the writing down of the Manx Language.-Preceding and following bishops:...

, the Welsh-born Bishop of Sodor and Man

Bishop of Sodor and Man

The Bishop of Sodor and Man is the Ordinary of the Diocese of Sodor and Man in the Province of York in the Church of England. The diocese covers the Isle of Man. The see is in the town of Peel where the bishop's seat is located at the Cathedral Church of St German, elevated to cathedral status on 1...

(1605–33). The early Manx script does have some similarities with orthographical systems found occasionally in Scotland and in Ireland for the transliteration of Gaelic, such as the Book of the Dean of Lismore

Book of the Dean of Lismore

The Book of the Dean of Lismore is a famous Scottish manuscript, compiled in eastern Perthshire in the first half of the 16th century. The chief compiler, after whom it is named, was James MacGregor , vicar of Fortingall and titular Dean of Lismore Cathedral, although there are other probable...

, as well as in some cases extensive texts based on English and Scottish English orthographical practices of the time. Little secular Manx literature

Manx literature

Manx literature is literature in the Manx language.The earliest datable text in Manx , a poetic history of the Isle of Man from the introduction of Christianity, dates to the 16th century at the latest....

has been preserved.

When the Anglican church authorities commenced the production of written literature in the language in the 18th century, the system developed by John Philips was further "anglicized", the one Welsh-retention being the use of ⟨y⟩ to represent schwa (e.g. [kaːβəl] "horse" and [kuːnə] "help" as well as /ɪ/ (e.g. [fɪz] “knowledge”), though it is also used to represent [j], as in English (e.g. [ə juːan] "John" (vocative), [jiːəst] "fish").

Later pieces included short stories and poetry. Translations also occurred, notably of Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books, with a total of over ten thousand individual lines of verse...

in 1796.

In 2006, the first full length novel in Manx, Dunveryssyn yn Tooder-Folley (The Vampire Murders) was published by Brian Stowell, after being serialised in the press.

The Railway Series

Although the books of The Railway SeriesThe Railway Series

The Railway Series is a set of story books about a railway system located on the fictional Island of Sodor. There are 42 books in the series, the first being published in 1945. Twenty-six were written by the Rev. W. Awdry, up to 1972. A further 16 were written by his son, Christopher Awdry; 14...

by the Reverend W. Awdry were written in English, Manx had a significant influence on the world in which they were set. Thomas the Tank Engine

Thomas the Tank Engine

Thomas the Tank Engine is a fictional steam locomotive in The Railway Series books by the Reverend Wilbert Awdry and his son, Christopher. He became the most popular character in the series, and the accompanying television spin-off series, Thomas and Friends.Thomas is a tank engine, painted blue...

and his fellow locomotive characters live on the fictional Island of Sodor, which is to the east of the Isle of Man, but at the same time loosely based on it. It has its own language "Sudric", which "is fast dying out and is akin to Manx and Gaelic" – but the difference between Manx and Sudric is not enough to prevent the two communities understanding one another.

A lot of the names, are clearly based on Manx forms, but often the nouns are inverted to match English word order. Some of the locations have quasi-Manx names, e.g. Killdane, which comes from "Keeill-y-Deighan" (Church of the Devil), hills are called Knock and Cronk, while "Nagh Beurla", means "I speak no English", a distortion of the Manx. The names of some of the 'historical' characters – used in the background but not appearing in the stories – were taken from locations on the Isle of Man, such as Sir Crosby Marown (Crosby

Crosby, Isle of Man

Crosby is a small village 6 km west of Douglas, Isle of Man on the Isle of Man. It has a population of about 900. The River Dhoo flows through the village.-Village:...

being a small village in the parish of Marown) and Harold Regaby.

Consonants

The consonant phonemes of Manx are as follows:| Bilabial Bilabial consonant In phonetics, a bilabial consonant is a consonant articulated with both lips. The bilabial consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:... |

Labio- dental Labiodental consonant In phonetics, labiodentals are consonants articulated with the lower lip and the upper teeth.-Labiodental consonant in IPA:The labiodental consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:... |

Dental | Alveolar Alveolar consonant Alveolar consonants are articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior alveolar ridge, which is called that because it contains the alveoli of the superior teeth... |

Post- alveolar Postalveolar consonant Postalveolar consonants are consonants articulated with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge, further back in the mouth than the alveolar consonants, which are at the ridge itself, but not as far back as the hard palate... |

Palatal Palatal consonant Palatal consonants are consonants articulated with the body of the tongue raised against the hard palate... |

Palato- velar Palatalization In linguistics, palatalization , also palatization, may refer to two different processes by which a sound, usually a consonant, comes to be produced with the tongue in a position in the mouth near the palate.... |

Velar Velar consonant Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate, the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum).... |

Labio- velar |

Glottal Glottal consonant Glottal consonants, also called laryngeal consonants, are consonants articulated with the glottis. Many phoneticians consider them, or at least the so-called fricative, to be transitional states of the glottis without a point of articulation as other consonants have; in fact, some do not consider... |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive Stop consonant In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or an oral stop, is a stop consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases. The occlusion may be done with the tongue , lips , and &... |

p | b | t̪ | d̪ | tʲ | dʲ | kʲ | ɡʲ | k | ɡ | ||||||||||

| Fricative Fricative consonant Fricatives are consonants produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate, in the case of German , the final consonant of Bach; or... |

f | v | s | ʃ | xʲ | ɣʲ | x | ɣ | h | |||||||||||

| Nasal Nasal consonant A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :... |

m | n | nʲ | ŋ | ||||||||||||||||

| Trill Trill consonant In phonetics, a trill is a consonantal sound produced by vibrations between the articulator and the place of articulation. Standard Spanish <rr> as in perro is an alveolar trill, while in Parisian French it is almost always uvular.... |

r | |||||||||||||||||||

| Approximant Approximant consonant Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough or with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do produce a turbulent airstream, and vowels, which produce no... |

j | w | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lateral Lateral consonant A lateral is an el-like consonant, in which airstream proceeds along the sides of the tongue, but is blocked by the tongue from going through the middle of the mouth.... |

l | lʲ | ||||||||||||||||||

The voiceless plosives are pronounced with aspiration

Aspiration (phonetics)

In phonetics, aspiration is the strong burst of air that accompanies either the release or, in the case of preaspiration, the closure of some obstruents. To feel or see the difference between aspirated and unaspirated sounds, one can put a hand or a lit candle in front of one's mouth, and say pin ...

. The dental, postalveolar and palato-velar plosives /t̪ d̪ tʲ dʲ kʲ/ are affricated to [t̪͡θ d̪͡ð t͡ʃ d͡ʒ kʲ͡ç] in many contexts.

Manx has an optional process of lenition

Lenition

In linguistics, lenition is a kind of sound change that alters consonants, making them "weaker" in some way. The word lenition itself means "softening" or "weakening" . Lenition can happen both synchronically and diachronically...

of plosives between vowels, whereby voiced plosives and voiceless fricatives become voiced fricatives and voiceless plosives become either voiced plosives or voiced fricatives. This process introduces the allophone

Allophone

In phonology, an allophone is one of a set of multiple possible spoken sounds used to pronounce a single phoneme. For example, and are allophones for the phoneme in the English language...

s [β ð z ʒ] to the series of voiced fricatives in Manx. The voiced fricative [ʒ] may be further lenited to [j], and [ɣ] may disappear altogether. Examples include:

Voiceless plosive to voiced plosive → [d̪]: [ˈbrad̪aɡ] "flag, rag" → [ɡ]: [ˈpɛɡə] "sin"

Voiceless plosive to voiced fricative → [v]: [ˈkavan] "cup" → [ð]: [ˈbɛːða] "boat" → [ɣ]: [ˈfiːɣəl] "tooth"

Voiced plosive to voiced fricative → [v]: [ˈkaːvəl] "horse" → [ð]: [ˈɛðənʲ] "face" → [ʒ]: [ˈpaːʒər] "prayer" → [ʒ] → [j]: [ˈmaːʒə], [ˈmaːjə] "stick" → [ɣ]: [ˈroɣət] "born"

Voiceless fricative to voiced fricative → [ð] or [z]: [ˈpuːðitʲ] or [ˈpuːzitʲ] "married" → [ð]: [ˈʃaːðu] "stand" → [ʒ]: [ˈɛːʒax] "easy" → [ʒ] → [j]: [ˈt̪ɔʒax], [ˈt̪ɔjax] "beginning" → [ɣ]: [ˈbɛːɣə] "live" → [ɣ] → : [ʃaː] "past"

Another optional process of Manx phonology is pre-occlusion

Pre-occlusion

Pre-occlusion is a phonological process, involving the insertion of a very short plosive consonant before a sonorant consonant. In Manx, this applies to stressed monosyllabic words , and is also found in Cornish on certain stressed syllables. The inserted consonant is homorganic with the following...

, the insertion of a very short plosive consonant before a sonorant consonant. In Manx, this applies to stressed monosyllabic words (i.e. words one syllable long). The inserted consonant is homorganic with the following sonorant, which means it has the same place of articulation

Place of articulation

In articulatory phonetics, the place of articulation of a consonant is the point of contact where an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract between an articulatory gesture, an active articulator , and a passive location...

. Long vowels are often shortened before pre-occluded sounds. Examples include: → [ᵇm]: /t̪roːm/ → [t̪roᵇm] "heavy" → [ᵈn]: /kʲoːn/ → [kʲoᵈn] "head" → [ᵈnʲ]: /eːnʲ/ → [eːᵈnʲ], [eᵈnʲ] "birds" → [ᶢŋ]: /loŋ/ → [loᶢŋ] "ship" → [ᵈl]: /ʃuːl/ → [ʃuːᵈl] "walking"

The trill /r/ is realised as a one- or two-contact flap [ɾ] at the beginning of syllable, and as a stronger trill [r] when preceded by another consonant in the same syllable. At the end of a syllable, /r/ can be pronounced either as a strong trill [r] or, more frequently, as a weak fricative [ɹ̝], which may vocalise to a nonsyllabic [ə̯] or disappear altogether. This vocalisation may be due to the influence of Manx English

Manx English

Manx English, or Anglo-Manx, is the historic dialect of English spoken on the Isle of Man, though today in decline. It has many borrowings from the original Manx language, a Goidelic language, and it differs widely from any other English, including other Celtic-derived dialects such as Welsh...

, which is itself a non-rhotic accent. Examples of the pronunciation of /r/ include: "snare" [ˈɾibə] "bread" [ˈaɾan] "big" [muːr], [muːɹ̝], [muːə̯], [muː]

Vowels

The vowel phonemes of Manx are as follows:| Short Vowel length In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived duration of a vowel sound. Often the chroneme, or the "longness", acts like a consonant, and may etymologically be one, such as in Australian English. While not distinctive in most dialects of English, vowel length is an important phonemic factor in... |

Long | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front Front vowel A front vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a front vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far in front as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Front vowels are sometimes also... |

Central Central vowel A central vowel is a type of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a central vowel is that the tongue is positioned halfway between a front vowel and a back vowel... |

Back Back vowel A back vowel is a type of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the tongue is positioned as far back as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant. Back vowels are sometimes also called dark... |

Front | Central | Back | |

| Close Close vowel A close vowel is a type of vowel sound used in many spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a close vowel is that the tongue is positioned as close as possible to the roof of the mouth without creating a constriction that would be classified as a consonant.This term is prescribed by the... |

i | u | iː | uː | ||

| Mid Mid vowel A mid vowel is a vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a mid vowel is that the tongue is positioned mid-way between an open vowel and a close vowel... |

e | ə | o | eː | oː | |

| Open Open vowel An open vowel is defined as a vowel sound in which the tongue is positioned as far as possible from the roof of the mouth. Open vowels are sometimes also called low vowels in reference to the low position of the tongue... |

(æ) | a | (æː) | aː | ||

The status of æ and æː as separate phonemes is debatable, but is suggested by the allophony of certain words such as "is", "women", and so on. An alternative analysis is that Manx has the following system, where the vowels /a/ and /aː/ have allophones ranging from [ɛ]/[ɛː] through [æ]/[æː] to [a]/[aː]. As with Irish and Scottish Gaelic, there is a large amount of vowel allophony, such as that of /a/,/a:/. This depends mainly on the 'broad' and 'slender' status of the neighbouring consonants:

| Phoneme | "Slender" | "Broad" |

|---|---|---|

| /i/, /i:/ | [i], [i:] | [ɪ], [ɪ:] |

| /e/,/e:/ | [e]/[e:] | [ɛ]/[ɛ:] |

| /a/,/a:/ | [ɛ~æ]/[ɛ:~æ:] | [a]/[a:] |

| /ə/ | [ɨ] | [ə] |

| /əi/ (Middle Gaelic) | [i:] | [ɛ:],[ɯ:],[ɪ:] |

| /o/,/o:/ | [o],[o:] | [ɔ],[ɔ:] |

| /u/,/u:/ | [u],[u:] | [ø~ʊ],[u:] |

| /uə/ (Middle Gaelic) | [i:],[y:] | [ɪ:],[ɯ:],[u:] |

When stressed, /ə/ is realised as [ø].

Manx has a relatively large number of diphthong

Diphthong

A diphthong , also known as a gliding vowel, refers to two adjacent vowel sounds occurring within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: That is, the tongue moves during the pronunciation of the vowel...

s, all of them falling:

| Second element is /i/ | Second element is /u/ | Second element is /ə/ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First element is close | ui | iə • uə | |

| First element is mid | ei • əi • oi | eu • əu | |

| First element is open | ai | au |

Stress

Stress generally falls on the first syllable of a word in Manx, but in many cases, stress is attracted to a long vowel in the second syllable. Examples include: /bəˈɣeːn/ "sprite" /t̪aˈruːx/ "busy" /riːˈoːl/ "royal" /vonˈd̪eːʃ/ "advantage"Morphology

Manx nouns fall into one of two gendersGrammatical gender

Grammatical gender is defined linguistically as a system of classes of nouns which trigger specific types of inflections in associated words, such as adjectives, verbs and others. For a system of noun classes to be a gender system, every noun must belong to one of the classes and there should be...

, masculine or feminine. Nouns are inflected for number

Grammatical number

In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, and adjective and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions ....

(the plural

Plural