Jonathan Jennings

Encyclopedia

Jonathan Jennings was the first Governor of Indiana

and a nine-term congressman from Indiana

. Born in Readington, New Jersey, he studied law with his brother before immigrating to Indiana in 1806 where he took part in land speculation. He became involved in a personal dispute with the Governor William Henry Harrison

that led him to enter politics and set the tone for his early political career. He was elected as the Indiana Territory

's delegate to Congress

by dividing the pro-Harrison supporters and running as an anti-Harrison candidate. By 1812 he was the leader of the anti-slavery, anti-governor, and pro-statehood faction of the territorial government. He and his political allies triumphed in their goals and took control of the territorial assembly and dominated the affairs of the government after the resignation of Governor Harrison. At the Indiana Constitutional Convention

, Jennings was elected President. He was behind the effort to have a ban on slavery constitutionalized and was for the creation of a weak executive branch in favor of a strong legislative branch.

After Indiana was granted statehood, Jennings was elected to serve as the first Governor of Indiana

. He pressed for the construction of roads and schools, and negotiated the Treaty of St. Mary's

to open up central Indiana to American settlement. His opponents attacked his participation in the treaty negotiations as unconstitutional and brought impeachment proceedings against him; the impeachment measure was narrowly defeated by a vote of 15–13 following a month-long investigation and the resignation of the lieutenant governor. During his second term and following the Panic of 1819

, Jennings began to encounter financial problems because to his commitment to accept no salary; the situation was exacerbated by his inability to keep up with his business interests and run the state government simultaneously.

Jennings resigned during his second term as governor upon winning election to the United States House of Representatives. Jennings served another five terms in Congress, promoting federal spending on internal improvements

. Jennings had been a heavy drinker of whiskey since his early life. His addiction worsened after the death of his first wife and his development of heumatism]. The problem led to his defeat in his reelection campaign in 1830. His condition was such that he was unable to work his farm; his finances collapsed and his creditors sought to take his land holdings and Charlestown

farm. To protect him, his friend Senator John Tipton

, purchased his farm and permitted him to continue living there. After his death, his estate was sold by his creditors leaving no funds to purchase a headstone for his grave, which remained unmarked for fifty-seven years.

Historians have had varied interpretations of Jennings’ life and impact on the development of Indiana. Early state historians, like Jacob Piatt Dunn

and William Woollen, gave Jennings high praise and credited him with the defeat of the pro-slavery forces in Indiana and with laying the foundation of the state. More critical historians during the prohibition era, like Logan Eseray, described Jennings as a crafty and self-promoting politician and focused on his alcoholism. Modern historians, like Keith Mills, place Jennings’ importance between the two extremes, saying that the “state owes him a debt which could never be calculated.”

. His mother had also received medical training and assisted her husband in his practice. Around the year 1790, Jennings father became a frontier missionary and his family moved to Dunlap Creek in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

, where Jennings remained until his adulthood. After his mother’s death in 1792, he was raised by his older sister and brother, Sarah and Ebenezer. Jennings attended the nearby grammar school

in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

, and received a basic education. His classmates there included William Hendricks

and William W. Wick

, both of whom would later become his political allies.

Jennings left Pennsylvania in 1804 to live with his brother Obadiah in Cincinnati, Ohio

and apprentice in his law firm. He helped in a number of cases before the Ohio Supreme Court and was admitted to the bar the following year. In 1806 he moved to Jeffersonville

in the Indiana Territory

to open his own law practice. Jennings had difficulty earning an income as a lawyer, finding there were too few clients in the territory to keep him busy. In July he was invited to take a job by John Badollet, a friend who managed the Federal Land Office in Vincennes

. Along with Badollet, he engaged in land speculation. He obtained significant land holdings and made substantial profits.

in 1807 where he first began to have interactions with the territorial governor William Henry Harrison

. Harrison was from a well connected political family, had served as a officer in the Northwest Indian War

, was a former Congressman, and future United States Senator, Ambassador, and President. A dispute arose over Harrison’s proposal to ban the French resident of Vincennes from the university’s commons in which Jennings’ vote proved to be the deciding one in defeating the measure. Harrison was outraged and promptly resigned from the board and made disparaging public comments about Jennings’ character. Jennings was at that time an election candidate against an enemy of Harrison, Davis Floyd

, for the clerkship of the territorial legislature. Jennings dropped out of the race and guaranteeing the victory of anti-slavery Floyd who became an important political ally to Jennings. Harrison was further angered against Jennings' by the election, and returned to the university board where he was easily reelected as its president. He immediately ordered the creation of a commission to investigate the moral character of Jennings. Jennings in turn resigned from the board; he felt he was mistreated by Harrison. The situation created a considerable amount of personal animosity that prevailed for many years.

Jennings began writing articles for the Vincennes' Western Sun newspaper. The city was the center of the pro-slavery establishment in the territory. Jennings' parents had been raised him to be bitterly opposed to slavery. The issue was attracting widespread attention in the territory because of Harrison's recent attempts to legalize the institution. Many of Jennings' articles attacked Harrison's administration and its pro-slavery sentiments. By March 1809, Jennings came to believe that his future in the Harrison dominated western part of the territory was bleak, so he left Vincennes and moved to Charlestown

.

In 1808 Congressman Benjamin Parke

resigned from office and Harrison ordered a special election to fill the vacancy. Jennings entered the race against Harrison’s candidate Thomas Randolph. He campaigned across the territory, riding from settlement to settlement to give speeches against slavery. He spoke against what he believed to be the aristocratic tendencies of the territorial government, which was almost entirely appointed by the governor, and their attempts to legalize slavery and deny rights to the new immigrants to the territory. He found his greatest support among the growing Quaker community in the eastern part of the territory. On November 27, 1809, Jennings was elected as a delegate to the 11th Congress. The election was close and Jennings won by plurality, 429–405, with a third candidate taking eighty-one votes. Randolph challenged the election results and traveled to Washington D.C to take his case to the House of Representatives. Randolph claimed that one of the precincts did not follow the proper procedures for certifying the counting of their votes, and that the precinct's votes should be discarded. Once discarded, the revised vote totals would make Randolph the winner. A House committee took up the case and issued a resolution in Randolph's favor, and recommended a new election be held. Randolph immediately left for the Indiana territory to launch a new campaign for the seat, but the motion was ultimately defeated in the full house and Jennings was permitted to take his seat.

In 1810 Randolph challenged Jennings in his reelection bid, and this time Harrison came out to personally stump on Randolph’s behalf. Jennings again focused on the slavery issue and tied Randolph to Harrison’s continued attempt to legalize the institution. He also attempted to expand his political base by stumping among the disaffected French residents of the territory. The election was the first in the territory where the legislature was also to be popularly elected. The pro-slavery faction had suffered a significant setback because the Illinois Territory had been separated from Indiana Territory just before the election, cutting Harrison off from most of his supporters. Jennings and the anti-slavery candidates triumphed in the election and began enacting a legislative agenda repudiating Harrison and his pro-slavery policies. Randolph was angry with his second electoral loss and began haranguing Jennings’ supporters and challenged one to a duel

In 1810 Randolph challenged Jennings in his reelection bid, and this time Harrison came out to personally stump on Randolph’s behalf. Jennings again focused on the slavery issue and tied Randolph to Harrison’s continued attempt to legalize the institution. He also attempted to expand his political base by stumping among the disaffected French residents of the territory. The election was the first in the territory where the legislature was also to be popularly elected. The pro-slavery faction had suffered a significant setback because the Illinois Territory had been separated from Indiana Territory just before the election, cutting Harrison off from most of his supporters. Jennings and the anti-slavery candidates triumphed in the election and began enacting a legislative agenda repudiating Harrison and his pro-slavery policies. Randolph was angry with his second electoral loss and began haranguing Jennings’ supporters and challenged one to a duel

. Randolph was stabbed three times in the fight, leading him to end his political career.

In his first full term in Congress, Jennings ratcheted up his attacks on Harrison, accusing him of using his office for personal gain, of taking part in questionable land speculation deals, and needlessly of raising tensions with the Native American tribes on the frontier. When Harrison was up for reappointment as governor in 1810, Jennings sent a scathing letter to President James Madison

recommending against his reappointment. Harrison, however, also had a number of powerful allies in Washington who argued on his behalf and aided him in securing reappointment. In 1811, hostilities broke out on the frontier between the Americans and the native tribes culminating in the Battle of Tippecanoe

in November. Jennings successfully promoted the passage of a bill to grant all veterans of the battle double pay, and to give the widows and orphans of those killed a pension for five years. Privately he wrote to his friends in the territory that he believed Harrison was at fault for agitating the situation and accused him of causing the needless loss of life.

As calls for war with Great Britain

increased, Jennings was not among the war hawks, but ultimately supported the declaration beginning the War of 1812

. Early in the war, Harrison was commissioned as a military general and dispatched to defend the frontier and invade Canada

, causing him to resign as governor. Jennings saw the resignation as a victory and he and his allies moved quickly to take advantage of the situation. The elderly acting-governor, John Gibson

, did not challenge the territorial legislature's agenda and allowed them to have their way in most matters. The legislature proceeded to move the capital away from pro-Harrison Vincennes and embark on a course for statehood. By the time Harrison’s successor, Thomas Posey

, was appointed and arrived in the territory the legislature had become entrenched in power.

. The election campaign was the most divisive in Jennings’ career; Taylor derided Jennings as a "pitiful coward" and not doing enough to protect the territory. He even went so far as to challenge Jennings to a duel, but Jennings refused. Jennings ran on the slavery issue again, fielding his new motto: "No slavery in Indiana,” and tying Taylor to the pro-slavery movement. He easily won reelection thanks to his growing base of support which had expanded to include the growing community of Harmonists

.

During his third term in Congress, Jennings began advocating that statehood be granted to Indiana, but held off formally introducing legislation until the end of the War of 1812. He developed jaundice

in 1813 and was too ill to attend Congress for a few weeks. He had been a heavy drinker of alcohol since his youth, which brought on the disease. He soon recovered and continued his push for statehood, and ran on that issued in his 1814 reelection campaign. He won again, and introduced a statehood bill to Congress. In 1815 the House of Representatives began debate on the measure, and in early 1816 the bill passed. The Enabling Act granted Indiana the right to form a government and write a constitution

. Governor Posey was concerned that the territory was too underpopulated to provide sufficient tax revenue to fund a state government. In a letter to President Madison, he recommended the President veto the bill and hold off on statehood for another three years, which would allow him to finish his term as governor. Madison signed the bill despite Posey's plea.

Dennis Pennington

, a leading member of the territorial legislature, was able to promote the election of many anti-slavery delegates to the constitutional convention. At the convention in 1816, held in the new capital of Corydon

, Jennings' partisans were able to elect him as president of the assembly, which permitted him to appoint all the committee chairmen of the convention. This gave Jennings a great sway in influencing the body, and allowed him and his allies to have their way in the writing of the constitution. Much of the constitution was directly copied from that of other states, but a few items were new and unique to Indiana. Jennings was the architect of the unique provisions. Among them was the wording of the ban on slavery, which prevented slavery from being legalized, even by constitutional amendment. The governor was also given limited powers, primarily as a final act of repudiation of the territorial governors. Most power was given to the Indiana General Assembly

. At the end of the convention Jennings announced his candidacy for governor.

In 1818, Jennings began promoting a plan of large scale plan for internal improvements in the state. Most of the projects where directed toward the constructions of roads, canals, and other projects that were would enhance the commercial appeal and economic viability of the state. The General Assembly approved a number of measures and $100,000 for creating roads and allowed for the improvement of some of the more important routes, but was considerably short of the amount Jennings wanted. The largest project authorized was the Indiana Canal Company

, who the state granted over $1.5 million over a period of several years. Jennings also pushed for the quick creation of a state funded school system as called for in the constitution, but the General Assembly believed priority should be given to creating government infrastructure. The state was experiencing budget shortages because the low tax revenues predicted by Posey, and Jennings had to pursue other means to finance the projects, mainly by issuing government bonds to the state bank and the sale of public land. The spending and borrowing led to problems in the short term budget, but despite early setbacks, the infrastructure improvements initiated by Jennings had the desired effects in the decades after his governorship; Indiana’s population of sixty-five thousand in 1816 surpassed one million by 1850.

When Jennings took office, there was only one bank in the state. To remedy the problem, the state granted a charter to establish the Farmer and Mechanics Bank in Madison

and expanded the existing Bank of Vincennes and funded the opening of new branches in Corydon and Brookville

. Both banks became involved in land speculation, and there were numerous reports of corruption at the Bank of Vincennes. The collapse of land value brought on by the Panic of 1819

put the banks in financial distress; they were both insolvent by 1824. The poor accessibility to capital led the state to halt its improvement programs and the Indiana Canal Company folded because of lack of funding. Most of Jennings second term was spent grappling with the financial difficulties and attempting to put the state on a firm footing. Tax revenues and land sales remained low and state revenue was not sufficient to pay the bonds used to finance the defunct canal company. The General Assembly was forced to significantly depreciate their value, harming the state credit and making it difficult for to secure new loans.

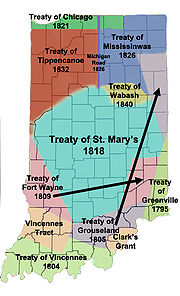

In late 1818, Jennings served as a United States Commissioner to negotiate a treaty with the Native Americans

In late 1818, Jennings served as a United States Commissioner to negotiate a treaty with the Native Americans

in the northern and central parts of Indiana. The treaty he negotiated, known as the Treaty of St. Mary's

, allowed the state to purchase millions of acres of land and opened up most of central Indiana to American settlement.

The state constitution forbade a person to hold a position in both the state and federal government simultaneously, and Jennings political enemies seized on the opportunity to attempt to force him out of office. In the Indiana House of Representatives

the opposition launched impeachment proceedings against him before he had returned from the negotiations. Upon learning of the situation, Jennings was “mortified” that his actions were being questioned and he proceeded to burn all the documents granting him authority from the federal government. Lieutenant Governor

Christopher Harrison

proclaimed himself acting-governor in Jennings' absence and declared that Jennings' actions were equal to a resignation. When Jennings returned from the negotiations, there was still contention in the General Assembly as to who to recognize as the legitimate governor. The legislature called both Jennings and Harrison before them to be interrogated for their actions. Jennings declined to appear stating the Assembly had no such authority over him, and Harrison declined to appear unless the Assembly would address him as “acting-governor”. With neither of the two men willing to meet with the legislature, the Assembly demanded copies of the documents that Jennings received from the federal government to prove he was not acting as their agent, to which he replied in a short letter which stated:

The legislature proceeded to summon everyone in the surrounding area who had any knowledge of the events at St Mary's, but found that none were certain of Jennings' exact role in the commission. After a short period of debate, the House passed a resolution 15 to 13 that Jennings would be recognized as the "rightful governor" and that the impeachment proceedings would be dropped. Christopher Harrison was outraged by the decision and resigned. He considered his honor tarnished and ran against Jennings in his reelection bid of 1820. Jennings took advantage of Harrison’s single issue by changing the topic of the election to the state’s financial situation. He offered to accept no salary from the state if elected to a second term. He won the election with 11,256 votes to Harrison’s 2,008.

Besides harming the state's finances, the Panic of 1819 also had a negative impact on Jennings’s financial affairs. He attempted shore up his position by soliciting a $1,000 loan from the Harmonists in a letter to political ally George Rapp

Besides harming the state's finances, the Panic of 1819 also had a negative impact on Jennings’s financial affairs. He attempted shore up his position by soliciting a $1,000 loan from the Harmonists in a letter to political ally George Rapp

, but he was turned down. He was finally able to procure money through loans from a number of different friends by granting mortgages on most of his land. The price of land decreased significantly, however, and he was forced to sell several tracts at a loss to cover his position before he could secure the loans. To complicate matters, Jennings was too busy with the state government to adequately manage his farm, which was not turning a profit, and having no income from his position in the government, his financial situation was quickly becoming dire.

Jennings had been spending large amounts of money to maintain his Corydon home, and frequently held large dinners with state officials and community leaders. In his most high-profile dinner, he hosted President James Monroe

and General Andrew Jackson

who were making a tour of the frontier states in 1819. The governorship only continued to grow as a financial burden to Jennings.

To remedy his problem, he decided he needed to return to Congress where his salary could cover his reduced expenses and allow him to return to prosperity. He made an arrangement with the wealthier congressman William Hendricks in which he would support Hendricks bid for the governorship in the upcoming election if Hendricks would resign from Congress and support Jennings in the special election for the seat. During the final year of his second three-year term as governor, Jennings ran unopposed for Congress and in 1822 he was easily elected as a Democratic-Republican to the 17th Congress. After winning the election, he resigned his position as governor and was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor

Ratliff Boon

; Hendricks ran unopposed and was subsequently elected to succeed Boon.

Jennings continued to promote internal infrastructure improvement in Congress and used the issue as a platform for the remainder of his time there. He won reelection four times and became a Jacksonian Republican in the 18th Congress

Jennings continued to promote internal infrastructure improvement in Congress and used the issue as a platform for the remainder of his time there. He won reelection four times and became a Jacksonian Republican in the 18th Congress

. He switched his allegiance becoming an Adams Republican in the 19th and 20th Congress

es. He then aligned with the Anti-Jacksonians in the 21st Congress. During his terms, he introduced legislation to build more forts in the northwest, to grant federal funding for improvement projects in Indiana and Ohio, and led the debate in support of granting federal funds to build the nations longest canal, Wabash and Erie Canal

, through Indiana. After the contested election of President Andrew Jackson in 1824 the House of Representatives decided the election, and Jennings voted with the majority giving Jackson the presidency. He served twice as Grand Master of the Indiana Grand Lodge of Freemasons during the later 1820s. In 1824, William Henry Harrison returned to Indiana to stump for the Adams Presidential candidate and Jennings and Harrison found themselves on the same side. The two men toured the state together, endorsing John Quincy Adams

. They also gave speeches where they indicated their past political feud was over. In 1825 Jennings was a candidate in the Indiana General Assembly for the United States Senate

. On the first ballot he came in second, and on the second ballot he came in third, losing the vote in the General Assembly to incumbent governor William Hendricks.

Jennings’ wife died in 1826 after a protected illness; the couple had no children. Jennings was deeply saddened by her loss and began to drink liquor more heavily. In a letter to his sister he also noted that he was afflicted with severe rheumatism

. While drinking in 1828, an accident occurred in which plaster from the ceiling of his Washington D.C. boarding room fell upon his head, severely injuring him and preventing him from attending Congress for nearly a month. Later that year he remarried to Clarissa Barbee, but his drinking condition only worsened and he was frequently inebriated. In his final term in office, the House journals show that he introduced no legislation, was frequently not present to vote on matters, and only once delivered a speech. His friends took note of his situation, and a group led by Senator John Tipton

decided to attempt to block his 1830 reelection bid. Tipton enlisted the help of war hero John Carr

to oppose Jennings in the election while also arranging for other popular Anti-Jackson men to enter the race and divide Jennings' supporters. Tipton hoped that the need to work would force Jennings to give up his heavy drinking. Carr defeated Jennings, who left office on March 3, 1831.

to buy up the debt on Jennings’s other holdings; in total Jennings owed the two men several thousand dollars in addition to hundreds of dollars in loans to various other individuals. Tipton allowed Jennings to remain on the farm without paying his debt, but Lanier began selling some of Jennings property holdings to recover some of his money when it became apparent that Jennings had no intention of paying his debt.

Despite his destitution, Jennings made no attempt to repair his fortunes. Feeling that he may have been mistaken to force him out of public service, Tipton helped Jennings find a new position in hope that it would stir him to recover, and secured him an appointment to negotiate a treaty with native tribes in northern Indiana. Jennings attended the negotiations of the Treaty of Tippecanoe

to purchase all the tribal held lands in northern Indiana, but the delegation was able to secure the purchase of only lands in northwestern Indiana. Afterwards, Jennings again returned to his farm where his health steadily declined. He spent considerable time a local tavern and often was unable to reach his home after leaving and was discovered on multiple occasions to be sleeping in ditches and neighborhood barns. Jennings died of a heart attack most likely brought on by another bout with jaundice on July 26, 1834 near Charlestown. He was interred after a brief ceremony and was buried in an unmarked grave on his farm; he lacked the funds to purchase a headstone.

and Jennings County

are both named in his honor.

Historians have varied interpretations of Jennings’ life and his impact on the development of Indiana. The state’s early historians, like William Woollen and Jacob Piatt Dunn

, wrote of Jennings in an almost mythical manner and focused on the strong positive leadership he provided Indiana in its formative years. Dunn referred to Jennings as the “young Hercules”, and praised his crusade against Harrison and slavery. During the prohibition era in the early twentieth century, historians like Logan Eseray and Arthur Blythe wrote more critical works of Jennings, describing him as a “crafty and self promoting politician,” and dismissed his importance and impact on Indiana, saying the legislature and its leading men set the tone of the era. They tended focused on his alcoholism and destitution in later life and the basis of their opinions. Modern historians like Howard Peckham and Keith Miller say that the truth of Jennings’ legacy lies somewhere between the two extremes. Miller, quoting Woollen, says that the state “owes him a debt which can never be calculated” for his role in preventing the spread of slavery and in changing the future of the state by pulling it out of the sphere of the southern slave states and making Indiana a truly northern free state.

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Governor of Indiana

The Governor of Indiana is the chief executive of the state of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term, and responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government. The governor also shares power with other statewide...

and a nine-term congressman from Indiana

Indiana

Indiana is a US state, admitted to the United States as the 19th on December 11, 1816. It is located in the Midwestern United States and Great Lakes Region. With 6,483,802 residents, the state is ranked 15th in population and 16th in population density. Indiana is ranked 38th in land area and is...

. Born in Readington, New Jersey, he studied law with his brother before immigrating to Indiana in 1806 where he took part in land speculation. He became involved in a personal dispute with the Governor William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

that led him to enter politics and set the tone for his early political career. He was elected as the Indiana Territory

Indiana Territory

The Territory of Indiana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, until November 7, 1816, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana....

's delegate to Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

by dividing the pro-Harrison supporters and running as an anti-Harrison candidate. By 1812 he was the leader of the anti-slavery, anti-governor, and pro-statehood faction of the territorial government. He and his political allies triumphed in their goals and took control of the territorial assembly and dominated the affairs of the government after the resignation of Governor Harrison. At the Indiana Constitutional Convention

Constitution of Indiana

There have been two Constitutions of the State of Indiana. The first constitution was created when the Territory of Indiana sent forty-three delegates to a constitutional convention on June 10, 1816 to establish a constitution for the proposed State of Indiana after the United States Congress had...

, Jennings was elected President. He was behind the effort to have a ban on slavery constitutionalized and was for the creation of a weak executive branch in favor of a strong legislative branch.

After Indiana was granted statehood, Jennings was elected to serve as the first Governor of Indiana

Governor of Indiana

The Governor of Indiana is the chief executive of the state of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term, and responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government. The governor also shares power with other statewide...

. He pressed for the construction of roads and schools, and negotiated the Treaty of St. Mary's

Treaty of St. Mary's

The Treaty of St. Mary's was signed on October 6, 1818 at Saint Mary's, Ohio between representatives of the United States and the Miami tribe and others living in their territory. The accord contained seven articles. Based on the terms of the accord, the Miami ceded to the United States...

to open up central Indiana to American settlement. His opponents attacked his participation in the treaty negotiations as unconstitutional and brought impeachment proceedings against him; the impeachment measure was narrowly defeated by a vote of 15–13 following a month-long investigation and the resignation of the lieutenant governor. During his second term and following the Panic of 1819

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first major financial crisis in the United States, and had occurred during the political calm of the Era of Good Feelings. The new nation previously had faced a depression following the war of independence in the late 1780s and led directly to the establishment of the...

, Jennings began to encounter financial problems because to his commitment to accept no salary; the situation was exacerbated by his inability to keep up with his business interests and run the state government simultaneously.

Jennings resigned during his second term as governor upon winning election to the United States House of Representatives. Jennings served another five terms in Congress, promoting federal spending on internal improvements

Internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canals, harbors and navigation improvements...

. Jennings had been a heavy drinker of whiskey since his early life. His addiction worsened after the death of his first wife and his development of heumatism]. The problem led to his defeat in his reelection campaign in 1830. His condition was such that he was unable to work his farm; his finances collapsed and his creditors sought to take his land holdings and Charlestown

Charlestown, Indiana

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 5,993 people, 2,341 households, and 1,615 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,570.0 people per square mile . There were 2,489 housing units at an average density of 1,067.4 per square mile...

farm. To protect him, his friend Senator John Tipton

John Tipton

John Shields Tipton was an American politician.Tipton was born in what is now Sevier County, Tennessee. His father was killed by Native Americans. His great uncle, also named John, was a prominent man in the area...

, purchased his farm and permitted him to continue living there. After his death, his estate was sold by his creditors leaving no funds to purchase a headstone for his grave, which remained unmarked for fifty-seven years.

Historians have had varied interpretations of Jennings’ life and impact on the development of Indiana. Early state historians, like Jacob Piatt Dunn

Jacob Piatt Dunn

Jacob Piatt Dunn was an American historian and author of several books. He was instrumental in making the Indiana Historical Society an effective group, serving as its secretary for decades. He was also instrumental in the Indiana Public Library Commission...

and William Woollen, gave Jennings high praise and credited him with the defeat of the pro-slavery forces in Indiana and with laying the foundation of the state. More critical historians during the prohibition era, like Logan Eseray, described Jennings as a crafty and self-promoting politician and focused on his alcoholism. Modern historians, like Keith Mills, place Jennings’ importance between the two extremes, saying that the “state owes him a debt which could never be calculated.”

Family and background

Jonathan Jennings was born the son of Jacob and Mary Kennedy Jennings in Readington, New Jersey during 1784, the fifth of seven children. His father was a doctor and abolitionist Presbyterian ministerPreacher

Preacher is a term for someone who preaches sermons or gives homilies. A preacher is distinct from a theologian by focusing on the communication rather than the development of doctrine. Others see preaching and theology as being intertwined...

. His mother had also received medical training and assisted her husband in his practice. Around the year 1790, Jennings father became a frontier missionary and his family moved to Dunlap Creek in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Fayette County is a county located in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. As of the2010 census, the population was 136,606. The county is part of the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area....

, where Jennings remained until his adulthood. After his mother’s death in 1792, he was raised by his older sister and brother, Sarah and Ebenezer. Jennings attended the nearby grammar school

Grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and some other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching classical languages but more recently an academically-oriented secondary school.The original purpose of mediaeval...

in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

Canonsburg is a borough in Washington County, Pennsylvania, southwest of Pittsburgh. Canonsburg was laid out by Colonel John Canon in 1789 and incorporated in 1802....

, and received a basic education. His classmates there included William Hendricks

William Hendricks

William Hendricks was a Democratic-Republican member of the House of Representatives from 1816 to 1822, the third Governor of Indiana from 1822 to 1825, and an Anti-Jacksonian member of the U.S. Senate from 1825 to 1837. He led much of his family into politics and founded one of the largest...

and William W. Wick

William W. Wick

William Watson Wick was a U.S. Representative from Indiana.The son of Presbyterian Minister the Rev. William Wick, and his wife Elizabeth the daughter of an officer in the Continental Army; the younger Mr...

, both of whom would later become his political allies.

Jennings left Pennsylvania in 1804 to live with his brother Obadiah in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

and apprentice in his law firm. He helped in a number of cases before the Ohio Supreme Court and was admitted to the bar the following year. In 1806 he moved to Jeffersonville

Jeffersonville, Indiana

Jeffersonville is a city in Clark County, Indiana, along the Ohio River. Locally, the city is often referred to by the abbreviated name Jeff. It is directly across the Ohio River to the north of Louisville, Kentucky along I-65. The population was 44,953 at the 2010 census...

in the Indiana Territory

Indiana Territory

The Territory of Indiana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, until November 7, 1816, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana....

to open his own law practice. Jennings had difficulty earning an income as a lawyer, finding there were too few clients in the territory to keep him busy. In July he was invited to take a job by John Badollet, a friend who managed the Federal Land Office in Vincennes

Vincennes, Indiana

Vincennes is a city in and the county seat of Knox County, Indiana, United States. It is located on the Wabash River in the southwestern part of the state. The population was 18,701 at the 2000 census...

. Along with Badollet, he engaged in land speculation. He obtained significant land holdings and made substantial profits.

Confrontation with Harrison

Jennings' growing prominence helped him to secure an appointment to serve on the board of the Vincennes UniversityVincennes University

Vincennes University is a public university in Vincennes, Indiana, in the United States. Founded in 1801 as Jefferson Academy, VU is the oldest public institution of higher learning in Indiana. Since 1889, VU has been a two-year university, although baccalaureate degrees in seven select areas are...

in 1807 where he first began to have interactions with the territorial governor William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

. Harrison was from a well connected political family, had served as a officer in the Northwest Indian War

Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War , also known as Little Turtle's War and by various other names, was a war fought between the United States and a confederation of numerous American Indian tribes for control of the Northwest Territory...

, was a former Congressman, and future United States Senator, Ambassador, and President. A dispute arose over Harrison’s proposal to ban the French resident of Vincennes from the university’s commons in which Jennings’ vote proved to be the deciding one in defeating the measure. Harrison was outraged and promptly resigned from the board and made disparaging public comments about Jennings’ character. Jennings was at that time an election candidate against an enemy of Harrison, Davis Floyd

Davis Floyd

Davis Floyd was an Indiana Jeffersonian Republican politician who was convicted of aiding American Vice President Aaron Burr in the Burr conspiracy. Floyd was not convicted of treason however and returned to public life after several years working to redeem his reputation...

, for the clerkship of the territorial legislature. Jennings dropped out of the race and guaranteeing the victory of anti-slavery Floyd who became an important political ally to Jennings. Harrison was further angered against Jennings' by the election, and returned to the university board where he was easily reelected as its president. He immediately ordered the creation of a commission to investigate the moral character of Jennings. Jennings in turn resigned from the board; he felt he was mistreated by Harrison. The situation created a considerable amount of personal animosity that prevailed for many years.

Jennings began writing articles for the Vincennes' Western Sun newspaper. The city was the center of the pro-slavery establishment in the territory. Jennings' parents had been raised him to be bitterly opposed to slavery. The issue was attracting widespread attention in the territory because of Harrison's recent attempts to legalize the institution. Many of Jennings' articles attacked Harrison's administration and its pro-slavery sentiments. By March 1809, Jennings came to believe that his future in the Harrison dominated western part of the territory was bleak, so he left Vincennes and moved to Charlestown

Charlestown, Indiana

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 5,993 people, 2,341 households, and 1,615 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,570.0 people per square mile . There were 2,489 housing units at an average density of 1,067.4 per square mile...

.

In 1808 Congressman Benjamin Parke

Benjamin Parke

Benjamin Parke was a 19th-century American soldier and politician in the Indiana Territory and later state of Indiana.-Biography:...

resigned from office and Harrison ordered a special election to fill the vacancy. Jennings entered the race against Harrison’s candidate Thomas Randolph. He campaigned across the territory, riding from settlement to settlement to give speeches against slavery. He spoke against what he believed to be the aristocratic tendencies of the territorial government, which was almost entirely appointed by the governor, and their attempts to legalize slavery and deny rights to the new immigrants to the territory. He found his greatest support among the growing Quaker community in the eastern part of the territory. On November 27, 1809, Jennings was elected as a delegate to the 11th Congress. The election was close and Jennings won by plurality, 429–405, with a third candidate taking eighty-one votes. Randolph challenged the election results and traveled to Washington D.C to take his case to the House of Representatives. Randolph claimed that one of the precincts did not follow the proper procedures for certifying the counting of their votes, and that the precinct's votes should be discarded. Once discarded, the revised vote totals would make Randolph the winner. A House committee took up the case and issued a resolution in Randolph's favor, and recommended a new election be held. Randolph immediately left for the Indiana territory to launch a new campaign for the seat, but the motion was ultimately defeated in the full house and Jennings was permitted to take his seat.

Battle with Harrison

During his partial term in office, Jennings focused on learning the legislative process and attacking, whenever possible, Governor Harrison. As a territorial delegate, he was permitted to debate, serve on committees, and introduce legislation, but was not permitted to vote. During his time in Washington, Jennings had a small portrait of himself made which he had sent to Ann Gilmore Hay, the daughter of Jeffersonville merchant that he had begun courting.The painting is the only known authentic portrait of Jennings. Both of Jennings’ official portraits are based his 1809 portrait. (Miller, p. 134) After his first session in Congress ended, Jennings returned to the Indiana Territory where he married eighteen-year-old Ann. Her father had just died leaving her with no family. The couple returned to Washington where she remained briefly before leaving to live with Jennings’ sister, Ann, for the remainder of the session.

Duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.Duels in this form were chiefly practised in Early Modern Europe, with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period especially among...

. Randolph was stabbed three times in the fight, leading him to end his political career.

In his first full term in Congress, Jennings ratcheted up his attacks on Harrison, accusing him of using his office for personal gain, of taking part in questionable land speculation deals, and needlessly of raising tensions with the Native American tribes on the frontier. When Harrison was up for reappointment as governor in 1810, Jennings sent a scathing letter to President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

recommending against his reappointment. Harrison, however, also had a number of powerful allies in Washington who argued on his behalf and aided him in securing reappointment. In 1811, hostilities broke out on the frontier between the Americans and the native tribes culminating in the Battle of Tippecanoe

Battle of Tippecanoe

The Battle of Tippecanoe was fought on November 7, 1811, between United States forces led by Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Native American warriors associated with the Shawnee leader Tecumseh. Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa were leaders of a confederacy of...

in November. Jennings successfully promoted the passage of a bill to grant all veterans of the battle double pay, and to give the widows and orphans of those killed a pension for five years. Privately he wrote to his friends in the territory that he believed Harrison was at fault for agitating the situation and accused him of causing the needless loss of life.

As calls for war with Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

increased, Jennings was not among the war hawks, but ultimately supported the declaration beginning the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. Early in the war, Harrison was commissioned as a military general and dispatched to defend the frontier and invade Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, causing him to resign as governor. Jennings saw the resignation as a victory and he and his allies moved quickly to take advantage of the situation. The elderly acting-governor, John Gibson

John Gibson (Indiana)

John Gibson was a veteran of the French and Indian War, Lord Dunmore's War, the American Revolutionary War, Tecumseh's War, and the War of 1812. A delegate to the first Pennsylvania constitutional convention in 1790, and a merchant, he earned a reputation as a frontier leader and had good...

, did not challenge the territorial legislature's agenda and allowed them to have their way in most matters. The legislature proceeded to move the capital away from pro-Harrison Vincennes and embark on a course for statehood. By the time Harrison’s successor, Thomas Posey

Thomas Posey

Thomas Posey was an officer in the American Revolution, a general during peacetime, the third Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky, Governor of the Indiana Territory, and a Louisiana Senator.-Family and background:...

, was appointed and arrived in the territory the legislature had become entrenched in power.

Push for statehood

Jennings ran for reelection to Congress again in 1812 against another pro-slavery candidate, Waller TaylorWaller Taylor

Waller Taylor was an American military commander and politician.-Biography:Taylor was born in Lunenburg County, Virginia where he spent his entire childhood. He studied law and served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1800 to 1802.In 1804 he moved to Vincennes, Indiana and practiced law...

. The election campaign was the most divisive in Jennings’ career; Taylor derided Jennings as a "pitiful coward" and not doing enough to protect the territory. He even went so far as to challenge Jennings to a duel, but Jennings refused. Jennings ran on the slavery issue again, fielding his new motto: "No slavery in Indiana,” and tying Taylor to the pro-slavery movement. He easily won reelection thanks to his growing base of support which had expanded to include the growing community of Harmonists

New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana, United States. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat. The population was 916 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. Many of the old Harmonist buildings still stand...

.

During his third term in Congress, Jennings began advocating that statehood be granted to Indiana, but held off formally introducing legislation until the end of the War of 1812. He developed jaundice

Jaundice

Jaundice is a yellowish pigmentation of the skin, the conjunctival membranes over the sclerae , and other mucous membranes caused by hyperbilirubinemia . This hyperbilirubinemia subsequently causes increased levels of bilirubin in the extracellular fluid...

in 1813 and was too ill to attend Congress for a few weeks. He had been a heavy drinker of alcohol since his youth, which brought on the disease. He soon recovered and continued his push for statehood, and ran on that issued in his 1814 reelection campaign. He won again, and introduced a statehood bill to Congress. In 1815 the House of Representatives began debate on the measure, and in early 1816 the bill passed. The Enabling Act granted Indiana the right to form a government and write a constitution

Constitution of Indiana

There have been two Constitutions of the State of Indiana. The first constitution was created when the Territory of Indiana sent forty-three delegates to a constitutional convention on June 10, 1816 to establish a constitution for the proposed State of Indiana after the United States Congress had...

. Governor Posey was concerned that the territory was too underpopulated to provide sufficient tax revenue to fund a state government. In a letter to President Madison, he recommended the President veto the bill and hold off on statehood for another three years, which would allow him to finish his term as governor. Madison signed the bill despite Posey's plea.

Dennis Pennington

Dennis Pennington

Dennis Pennington was an early legislator in Indiana and the Indiana Territory, speaker of the first Indiana State Senate, speaker of the territorial legislature, a member of the Whig Party serving over 37 years in public office, and one of the founders of Indiana. He was also a stonemason and...

, a leading member of the territorial legislature, was able to promote the election of many anti-slavery delegates to the constitutional convention. At the convention in 1816, held in the new capital of Corydon

Corydon, Indiana

Corydon is a town in Harrison Township, Harrison County, Indiana, United States, founded in 1808, and is known as Indiana's First State Capital. After Vincennes, Corydon was the second capital of the Indiana Territory from May 1, 1813, until December 11, 1816. After statehood, the town was the...

, Jennings' partisans were able to elect him as president of the assembly, which permitted him to appoint all the committee chairmen of the convention. This gave Jennings a great sway in influencing the body, and allowed him and his allies to have their way in the writing of the constitution. Much of the constitution was directly copied from that of other states, but a few items were new and unique to Indiana. Jennings was the architect of the unique provisions. Among them was the wording of the ban on slavery, which prevented slavery from being legalized, even by constitutional amendment. The governor was also given limited powers, primarily as a final act of repudiation of the territorial governors. Most power was given to the Indiana General Assembly

Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate...

. At the end of the convention Jennings announced his candidacy for governor.

Internal improvements

In the election for Indiana's first governor, there was little active campaigning. Jennings beat Thomas Posey 5,211–3,934, by touting on his anti-slavery credentials in newspaper articles and in pamphlets. He served as governor and lived in Corydon for the duration of his term. He strongly condemned slavery in his inauguration speech, and as governor, he refined his stance on institution. He encouraged the General Assembly to enact laws to prevent the "unlawful attempts to seize and carry into bondage persons of color legally entitled to their freedom: and at the same time, as far as practical, to prevent those who rightfully owe service to the citizen of any other State of Territory, from seeking, within the limits of this State [Indiana], a refuge from the possession of their lawful masters." He acknowledge his position was a moderation of his earlier position to hinder the work of slave catchers, but he claimed it was needed in order to "maintain harmony among the states".In 1818, Jennings began promoting a plan of large scale plan for internal improvements in the state. Most of the projects where directed toward the constructions of roads, canals, and other projects that were would enhance the commercial appeal and economic viability of the state. The General Assembly approved a number of measures and $100,000 for creating roads and allowed for the improvement of some of the more important routes, but was considerably short of the amount Jennings wanted. The largest project authorized was the Indiana Canal Company

Indiana Canal Company

The Indiana Canal Company was a corporation first established in 1805 for the purpose of building a canal around the Falls of the Ohio on the Indiana side of the Ohio River...

, who the state granted over $1.5 million over a period of several years. Jennings also pushed for the quick creation of a state funded school system as called for in the constitution, but the General Assembly believed priority should be given to creating government infrastructure. The state was experiencing budget shortages because the low tax revenues predicted by Posey, and Jennings had to pursue other means to finance the projects, mainly by issuing government bonds to the state bank and the sale of public land. The spending and borrowing led to problems in the short term budget, but despite early setbacks, the infrastructure improvements initiated by Jennings had the desired effects in the decades after his governorship; Indiana’s population of sixty-five thousand in 1816 surpassed one million by 1850.

When Jennings took office, there was only one bank in the state. To remedy the problem, the state granted a charter to establish the Farmer and Mechanics Bank in Madison

Madison, Indiana

As of the census of 2000, there were 12,004 people, 5,092 households, and 3,085 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,402.9 people per square mile . There were 5,597 housing units at an average density of 654.1 per square mile...

and expanded the existing Bank of Vincennes and funded the opening of new branches in Corydon and Brookville

Brookville, Indiana

Brookville is a town in Brookville Township, Franklin County, Indiana, United States. The population was 2,625 at the 2000 census. The town is the county seat of Franklin County.-Geography:...

. Both banks became involved in land speculation, and there were numerous reports of corruption at the Bank of Vincennes. The collapse of land value brought on by the Panic of 1819

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first major financial crisis in the United States, and had occurred during the political calm of the Era of Good Feelings. The new nation previously had faced a depression following the war of independence in the late 1780s and led directly to the establishment of the...

put the banks in financial distress; they were both insolvent by 1824. The poor accessibility to capital led the state to halt its improvement programs and the Indiana Canal Company folded because of lack of funding. Most of Jennings second term was spent grappling with the financial difficulties and attempting to put the state on a firm footing. Tax revenues and land sales remained low and state revenue was not sufficient to pay the bonds used to finance the defunct canal company. The General Assembly was forced to significantly depreciate their value, harming the state credit and making it difficult for to secure new loans.

Treaty of St. Mary's

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

in the northern and central parts of Indiana. The treaty he negotiated, known as the Treaty of St. Mary's

Treaty of St. Mary's

The Treaty of St. Mary's was signed on October 6, 1818 at Saint Mary's, Ohio between representatives of the United States and the Miami tribe and others living in their territory. The accord contained seven articles. Based on the terms of the accord, the Miami ceded to the United States...

, allowed the state to purchase millions of acres of land and opened up most of central Indiana to American settlement.

The state constitution forbade a person to hold a position in both the state and federal government simultaneously, and Jennings political enemies seized on the opportunity to attempt to force him out of office. In the Indiana House of Representatives

Indiana House of Representatives

The Indiana House of Representatives is the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The House is composed of 100 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. House members serve two-year terms without term limits...

the opposition launched impeachment proceedings against him before he had returned from the negotiations. Upon learning of the situation, Jennings was “mortified” that his actions were being questioned and he proceeded to burn all the documents granting him authority from the federal government. Lieutenant Governor

Lieutenant Governor of Indiana

The Lieutenant Governor of Indiana is a constitutional office in the US State of Indiana. Republican Becky Skillman, whose term expires in January 2013, is the incumbent...

Christopher Harrison

Christopher Harrison

Christopher Harrison was the first Lieutenant Governor of Indiana, serving with Governor Jonathan Jennings. Harrison was briefly acting governor while Jennings' was conducting negotiation with the native tribes in northern Indiana, and later resigned from office over a dispute with Jennings...

proclaimed himself acting-governor in Jennings' absence and declared that Jennings' actions were equal to a resignation. When Jennings returned from the negotiations, there was still contention in the General Assembly as to who to recognize as the legitimate governor. The legislature called both Jennings and Harrison before them to be interrogated for their actions. Jennings declined to appear stating the Assembly had no such authority over him, and Harrison declined to appear unless the Assembly would address him as “acting-governor”. With neither of the two men willing to meet with the legislature, the Assembly demanded copies of the documents that Jennings received from the federal government to prove he was not acting as their agent, to which he replied in a short letter which stated:

"If I were in possession of any public documents calculated to advance the public interest it would give me pleasure to furnish them and I shall at all times be prepared to afford you any information which the constitution or laws of the State may require... If the difficulty real or supposed has grown out of the circumstances of my having been connected with the negotiation at St Mary's I feel it my duty to state to the committee that I acted from an entire conviction of its propriety and an anxious desire on my part to promote the welfare and accomplish the wishes of the whole people of the State in assisting to add a large and fertile tract of country to that which we already possess"

The legislature proceeded to summon everyone in the surrounding area who had any knowledge of the events at St Mary's, but found that none were certain of Jennings' exact role in the commission. After a short period of debate, the House passed a resolution 15 to 13 that Jennings would be recognized as the "rightful governor" and that the impeachment proceedings would be dropped. Christopher Harrison was outraged by the decision and resigned. He considered his honor tarnished and ran against Jennings in his reelection bid of 1820. Jennings took advantage of Harrison’s single issue by changing the topic of the election to the state’s financial situation. He offered to accept no salary from the state if elected to a second term. He won the election with 11,256 votes to Harrison’s 2,008.

Financial problems

George Rapp

Johann Georg Rapp was the founder of the religious sect called Harmonists, Harmonites, Rappites, or the Harmony Society....

, but he was turned down. He was finally able to procure money through loans from a number of different friends by granting mortgages on most of his land. The price of land decreased significantly, however, and he was forced to sell several tracts at a loss to cover his position before he could secure the loans. To complicate matters, Jennings was too busy with the state government to adequately manage his farm, which was not turning a profit, and having no income from his position in the government, his financial situation was quickly becoming dire.

Jennings had been spending large amounts of money to maintain his Corydon home, and frequently held large dinners with state officials and community leaders. In his most high-profile dinner, he hosted President James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

and General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

who were making a tour of the frontier states in 1819. The governorship only continued to grow as a financial burden to Jennings.

To remedy his problem, he decided he needed to return to Congress where his salary could cover his reduced expenses and allow him to return to prosperity. He made an arrangement with the wealthier congressman William Hendricks in which he would support Hendricks bid for the governorship in the upcoming election if Hendricks would resign from Congress and support Jennings in the special election for the seat. During the final year of his second three-year term as governor, Jennings ran unopposed for Congress and in 1822 he was easily elected as a Democratic-Republican to the 17th Congress. After winning the election, he resigned his position as governor and was succeeded by Lieutenant Governor

Lieutenant Governor of Indiana

The Lieutenant Governor of Indiana is a constitutional office in the US State of Indiana. Republican Becky Skillman, whose term expires in January 2013, is the incumbent...

Ratliff Boon

Ratliff Boon

Ratliff Boon was the second Governor of Indiana from September 12 to December 5, 1822, taking office following the resignation of Governor Jonathan Jennings' after his election to Congress...

; Hendricks ran unopposed and was subsequently elected to succeed Boon.

Return to Congress

18th United States Congress

The Eighteenth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1823 to March 3, 1825, during the seventh and eighth...

. He switched his allegiance becoming an Adams Republican in the 19th and 20th Congress

20th United States Congress

-House of Representatives:-Leadership:- Senate :* President: John C. Calhoun * President pro tempore: Samuel Smith - House of Representatives :* Speaker: Andrew Stevenson -Members:This list is arranged by chamber, then by state...

es. He then aligned with the Anti-Jacksonians in the 21st Congress. During his terms, he introduced legislation to build more forts in the northwest, to grant federal funding for improvement projects in Indiana and Ohio, and led the debate in support of granting federal funds to build the nations longest canal, Wabash and Erie Canal

Wabash and Erie Canal

The Wabash and Erie Canal was a shipping canal that linked the Great Lakes to the Ohio River via an artificial waterway. The canal provided traders with access from the Great Lakes all the way to the Gulf of Mexico...

, through Indiana. After the contested election of President Andrew Jackson in 1824 the House of Representatives decided the election, and Jennings voted with the majority giving Jackson the presidency. He served twice as Grand Master of the Indiana Grand Lodge of Freemasons during the later 1820s. In 1824, William Henry Harrison returned to Indiana to stump for the Adams Presidential candidate and Jennings and Harrison found themselves on the same side. The two men toured the state together, endorsing John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

. They also gave speeches where they indicated their past political feud was over. In 1825 Jennings was a candidate in the Indiana General Assembly for the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. On the first ballot he came in second, and on the second ballot he came in third, losing the vote in the General Assembly to incumbent governor William Hendricks.

Jennings’ wife died in 1826 after a protected illness; the couple had no children. Jennings was deeply saddened by her loss and began to drink liquor more heavily. In a letter to his sister he also noted that he was afflicted with severe rheumatism

Rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorder is a non-specific term for medical problems affecting the joints and connective tissue. The study of, and therapeutic interventions in, such disorders is called rheumatology.-Terminology:...

. While drinking in 1828, an accident occurred in which plaster from the ceiling of his Washington D.C. boarding room fell upon his head, severely injuring him and preventing him from attending Congress for nearly a month. Later that year he remarried to Clarissa Barbee, but his drinking condition only worsened and he was frequently inebriated. In his final term in office, the House journals show that he introduced no legislation, was frequently not present to vote on matters, and only once delivered a speech. His friends took note of his situation, and a group led by Senator John Tipton

John Tipton

John Shields Tipton was an American politician.Tipton was born in what is now Sevier County, Tennessee. His father was killed by Native Americans. His great uncle, also named John, was a prominent man in the area...

decided to attempt to block his 1830 reelection bid. Tipton enlisted the help of war hero John Carr

John Carr (Indiana)

John Carr was a U.S. Representative from Indiana.-Biography:Carr was born in Uniontown, Indiana. He moved with his parents to Clark County, Indiana, in 1806. There he attended the public schools....

to oppose Jennings in the election while also arranging for other popular Anti-Jackson men to enter the race and divide Jennings' supporters. Tipton hoped that the need to work would force Jennings to give up his heavy drinking. Carr defeated Jennings, who left office on March 3, 1831.

Retirement

Jennings retired with his wife to his home in Charlestown. His alcoholism continued to worsen to the point where he was unable to tend his farm. Without an income his creditors began moving to seize his estate. In 1832, Tipton purchased the mortgage on Jennings’s farm and enlisted the help of local financier James LanierJames Lanier

James Franklin Doughty Lanier was a entrepreneur who lived in Madison, Indiana prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War . Lanier became a wealthy banker with interests in pork packing, the railroads, and real-estate.-Biography:James Lanier was born in 1800 in Beaufort County, North Carolina...

to buy up the debt on Jennings’s other holdings; in total Jennings owed the two men several thousand dollars in addition to hundreds of dollars in loans to various other individuals. Tipton allowed Jennings to remain on the farm without paying his debt, but Lanier began selling some of Jennings property holdings to recover some of his money when it became apparent that Jennings had no intention of paying his debt.

Despite his destitution, Jennings made no attempt to repair his fortunes. Feeling that he may have been mistaken to force him out of public service, Tipton helped Jennings find a new position in hope that it would stir him to recover, and secured him an appointment to negotiate a treaty with native tribes in northern Indiana. Jennings attended the negotiations of the Treaty of Tippecanoe

Treaty of Tippecanoe

The Treaty of Tippecanoe was an agreement between the United States government and Native American tribes in Indiana on October 26, 1832.-Treaty:...

to purchase all the tribal held lands in northern Indiana, but the delegation was able to secure the purchase of only lands in northwestern Indiana. Afterwards, Jennings again returned to his farm where his health steadily declined. He spent considerable time a local tavern and often was unable to reach his home after leaving and was discovered on multiple occasions to be sleeping in ditches and neighborhood barns. Jennings died of a heart attack most likely brought on by another bout with jaundice on July 26, 1834 near Charlestown. He was interred after a brief ceremony and was buried in an unmarked grave on his farm; he lacked the funds to purchase a headstone.

Legacy

Following his death, Tipton sold Jennings’ farm and gave the proceeds as a gift to Jennings’ widow. Lanier took possession of his land holdings, and a great many small creditors from whom Jennings had solicited personal loans were left unpaid, leaving him sorely dislike among his community at the time of his death. On three separate occasions, petitions were brought before the Indiana General Assembly to purchase a grave stone for Jennings, but each attempt failed. A fourth petition was circulated in 1887 that finally received attention. The state granted the petition and a headstone was purchased by the state in 1888. A group of school children who attended Jennings’ funeral ceremony were the only witnesses of Jennings’ burial that were still living. After the site was independently verified three times, Jennings’ body was exhumed and moved the Charlestown cemetery where he was reburied with a headstone. Jonathan Jennings Elementary School in CharlestownCharlestown, Indiana

-Demographics:As of the census of 2000, there were 5,993 people, 2,341 households, and 1,615 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,570.0 people per square mile . There were 2,489 housing units at an average density of 1,067.4 per square mile...

and Jennings County

Jennings County, Indiana

Jennings County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2010, the population was 28,525. The county seat is Vernon.-History:...

are both named in his honor.

Historians have varied interpretations of Jennings’ life and his impact on the development of Indiana. The state’s early historians, like William Woollen and Jacob Piatt Dunn

Jacob Piatt Dunn

Jacob Piatt Dunn was an American historian and author of several books. He was instrumental in making the Indiana Historical Society an effective group, serving as its secretary for decades. He was also instrumental in the Indiana Public Library Commission...

, wrote of Jennings in an almost mythical manner and focused on the strong positive leadership he provided Indiana in its formative years. Dunn referred to Jennings as the “young Hercules”, and praised his crusade against Harrison and slavery. During the prohibition era in the early twentieth century, historians like Logan Eseray and Arthur Blythe wrote more critical works of Jennings, describing him as a “crafty and self promoting politician,” and dismissed his importance and impact on Indiana, saying the legislature and its leading men set the tone of the era. They tended focused on his alcoholism and destitution in later life and the basis of their opinions. Modern historians like Howard Peckham and Keith Miller say that the truth of Jennings’ legacy lies somewhere between the two extremes. Miller, quoting Woollen, says that the state “owes him a debt which can never be calculated” for his role in preventing the spread of slavery and in changing the future of the state by pulling it out of the sphere of the southern slave states and making Indiana a truly northern free state.

Territorial delegate

}}

}

}

Gubernatorial elections

}Indiana’s 2nd Congressional district

}}

}

}

}