John Redcliffe-Maud

Encyclopedia

John Primatt Redcliffe-Maud, Baron Redcliffe-Maud, GCB, CBE (3 February 1906 – 20 November 1982) was a British

civil servant and diplomat

.

Born in Bristol

, Maud was educated at Eton College

and New College, Oxford

. At Oxford

he was a member of the Oxford University Dramatic Society

(OUDS). In 1928, he gained a one-year scholarship

to Harvard University

. From 1929 to 1939, he was a Fellow

at University College, Oxford

.

During World War II

, he was Master

of Birkbeck College

and was also based at Reading Gaol, working for the Ministry of Food. He became a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1942, and after the war, he worked at the Ministry of Education

(1945–1952), rising to Permanent Secretary

and then the Ministry of Fuel and Power until 1958. He became a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1946, and was raised to a Knight Grand Cross in 1955. Inter alia, Maud appeared on the BBC

programme The Brains Trust

in 1958. He was High Commissioner

in South Africa

from 1959 to 1963, when he became Master of University College, Oxford, where he had been a Fellow before WWII.

In March 1964, Maud was appointed by Sir Keith Joseph

, at the request of local authority associations, to head a departmental committee looking into the management of local government. The Maud Committee reported three years later. During the course of the inquiry, Maud was chosen to head a Royal Commission

on the reform of all local government in England

. He was awarded a life peer

age, hyphenating his surname to become Baron Redcliffe-Maud, of the City and County of Bristol

in 1967.

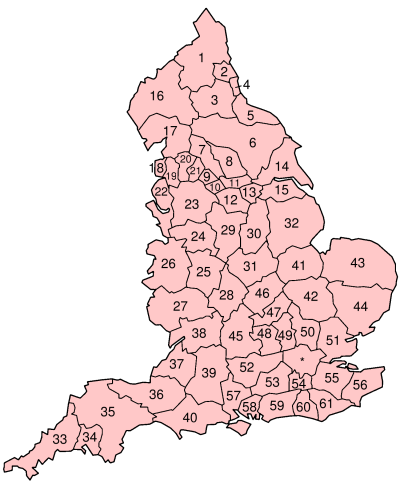

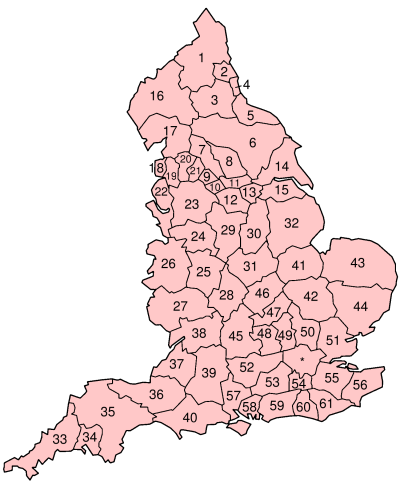

The Report of the Royal Commission on Local Government in England, popularly known as the Redcliffe-Maud Report

The Report of the Royal Commission on Local Government in England, popularly known as the Redcliffe-Maud Report

, was published in 1969. It advocated the wholesale reform of local authority boundaries and the institution of large unitary councils based on the principle of mixing rural and urban areas. Accepted by the Labour government of Harold Wilson

with minor changes, the opposition from rural areas convinced the Conservative opposition to oppose it and no further action was taken after the Conservatives won the 1970 general election

.

He retired as Master of University College in 1976, to be succeeded by the leading lawyer

Lord Goodman. His 1973 portrait by Ruskin Spear

can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery, London

. Another portrait hangs in the Hall at University College in Oxford.

Redcliffe-Maud was married to Jean Hamilton, who was educated at Somerville College, Oxford

. His son, Humphrey Maud, was one of Benjamin Britten

's favourite boys while he was at Eton. Sir John intervened to curtail Humphrey's frequent visits to stay with Britten on his own. The incident is described in John Bridcut's Britten's Children.

John Redcliffe-Maud is buried in Holywell Cemetery

, Oxford

. His archive is held by the London School of Economics

Library.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

civil servant and diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

.

Born in Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, Maud was educated at Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

and New College, Oxford

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

. At Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

he was a member of the Oxford University Dramatic Society

Oxford University Dramatic Society

The Oxford University Dramatic Society is the principal funding body and provider of theatrical services to the many independent student productions put on by students in Oxford, England...

(OUDS). In 1928, he gained a one-year scholarship

Scholarship

A scholarship is an award of financial aid for a student to further education. Scholarships are awarded on various criteria usually reflecting the values and purposes of the donor or founder of the award.-Types:...

to Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

. From 1929 to 1939, he was a Fellow

Fellow

A fellow in the broadest sense is someone who is an equal or a comrade. The term fellow is also used to describe a person, particularly by those in the upper social classes. It is most often used in an academic context: a fellow is often part of an elite group of learned people who are awarded...

at University College, Oxford

University College, Oxford

.University College , is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2009 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £110m...

.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he was Master

Master (college)

A Master is the title of the head of some colleges and other educational institutions. This applies especially at some colleges and institutions at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge .- See also :* Master A Master (or in female form Mistress) is the title of the head of some...

of Birkbeck College

Birkbeck, University of London

Birkbeck, University of London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and a constituent college of the federal University of London. It offers many Master's and Bachelor's degree programmes that can be studied either part-time or full-time, though nearly all teaching is...

and was also based at Reading Gaol, working for the Ministry of Food. He became a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1942, and after the war, he worked at the Ministry of Education

Ministry of Education (United Kingdom)

The administration of education policy in the United Kingdom began in the 19th century. Official mandation of education began with the Elementary Education Act 1870 for England and Wales, and the Education Act 1872 for Scotland...

(1945–1952), rising to Permanent Secretary

Permanent Secretary

The Permanent secretary, in most departments officially titled the permanent under-secretary of state , is the most senior civil servant of a British Government ministry, charged with running the department on a day-to-day basis...

and then the Ministry of Fuel and Power until 1958. He became a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1946, and was raised to a Knight Grand Cross in 1955. Inter alia, Maud appeared on the BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

programme The Brains Trust

The Brains Trust

The Brains Trust was a popular informational BBC radio and later television programme in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 50s.- History :...

in 1958. He was High Commissioner

High Commissioner

High Commissioner is the title of various high-ranking, special executive positions held by a commission of appointment.The English term is also used to render various equivalent titles in other languages.-Bilateral diplomacy:...

in South Africa

South Africa

The Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

from 1959 to 1963, when he became Master of University College, Oxford, where he had been a Fellow before WWII.

In March 1964, Maud was appointed by Sir Keith Joseph

Keith Joseph

Keith St John Joseph, Baron Joseph, Bt, CH, PC , was a British barrister and politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served in the Cabinet under three Prime Ministers , and is widely regarded to have been the "power behind the throne" in the creation of what came to be known as...

, at the request of local authority associations, to head a departmental committee looking into the management of local government. The Maud Committee reported three years later. During the course of the inquiry, Maud was chosen to head a Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

on the reform of all local government in England

Local government in the United Kingdom

The pattern of local government in England is complex, with the distribution of functions varying according to the local arrangements. Legislation concerning local government in England is decided by the Parliament and Government of the United Kingdom, because England does not have a devolved...

. He was awarded a life peer

Life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the Peerage whose titles cannot be inherited. Nowadays life peerages, always of baronial rank, are created under the Life Peerages Act 1958 and entitle the holders to seats in the House of Lords, presuming they meet qualifications such as...

age, hyphenating his surname to become Baron Redcliffe-Maud, of the City and County of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

in 1967.

Redcliffe-Maud Report

The Redcliffe–Maud Report is the name generally given to the report published by the Royal Commission on Local Government in England 1966–1969 under the chairmanship of Lord Redcliffe-Maud.-Terms of reference and membership:...

, was published in 1969. It advocated the wholesale reform of local authority boundaries and the institution of large unitary councils based on the principle of mixing rural and urban areas. Accepted by the Labour government of Harold Wilson

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, FSS, PC was a British Labour Member of Parliament, Leader of the Labour Party. He was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, winning four general elections, including a minority government after the...

with minor changes, the opposition from rural areas convinced the Conservative opposition to oppose it and no further action was taken after the Conservatives won the 1970 general election

United Kingdom general election, 1970

The United Kingdom general election of 1970 was held on 18 June 1970, and resulted in a surprise victory for the Conservative Party under leader Edward Heath, who defeated the Labour Party under Harold Wilson. The election also saw the Liberal Party and its new leader Jeremy Thorpe lose half their...

.

He retired as Master of University College in 1976, to be succeeded by the leading lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

Lord Goodman. His 1973 portrait by Ruskin Spear

Ruskin Spear

Ruskin Spear, CBE, RA was an English painter.Born in Hammersmith, Spear attended the local art school before going on to the Royal College of Art in 1930...

can be seen in the National Portrait Gallery, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. Another portrait hangs in the Hall at University College in Oxford.

Redcliffe-Maud was married to Jean Hamilton, who was educated at Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College, Oxford

Somerville College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and was one of the first women's colleges to be founded there...

. His son, Humphrey Maud, was one of Benjamin Britten

Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten, OM CH was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He showed talent from an early age, and first came to public attention with the a cappella choral work A Boy Was Born in 1934. With the premiere of his opera Peter Grimes in 1945, he leapt to...

's favourite boys while he was at Eton. Sir John intervened to curtail Humphrey's frequent visits to stay with Britten on his own. The incident is described in John Bridcut's Britten's Children.

John Redcliffe-Maud is buried in Holywell Cemetery

Holywell Cemetery

Holywell Cemetery is next to St Cross Church in Oxford, England. The cemetery is behind the church in St Cross Road, north of Longwall Street.-History:...

, Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

. His archive is held by the London School of Economics

London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science is a public research university specialised in the social sciences located in London, United Kingdom, and a constituent college of the federal University of London...

Library.

Books

- Redcliffe-Maud, John, Experiences of an Optimist: The Memoirs of John Redcliffe-Maud. London: Hamish HamiltonHamish HamiltonHamish Hamilton Limited was a British book publishing house, founded in 1931 eponymously by the half-Scot half-American Jamie Hamilton . Confusingly, Jamie Hamilton was often referred to as Hamish Hamilton...

, 1981. (ISBN 0-241-10569-2)

External links

- National Portrait Gallery information

- Catalogue of the Redcliffe-Maud papers at the Archives Division of the London School of EconomicsLondon School of EconomicsThe London School of Economics and Political Science is a public research university specialised in the social sciences located in London, United Kingdom, and a constituent college of the federal University of London...

.