Hitler's rise to power

Encyclopedia

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in Germany (at least formally) in September 1919 when Hitler

joined the political party that was known as the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (abbreviated as DAP, and later commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). This political party was formed and developed during the post-World War I

era. It was anti-Marxist and was opposed to the democratic post-war government of the Weimar Republic

and the Treaty of Versailles

; and it advocated extreme nationalism and Pan-Germanism

as well as virulent anti-Semitism

. Hitler's "rise" can be considered to have ended in March 1933, after the Reichstag

adopted the Enabling Act of 1933 in that month; President Paul von Hindenburg

had already appointed Hitler as Chancellor

on January 30, 1933 after a series of parliamentary elections and associated backstairs intrigues. The Enabling Act — when used ruthlessly and with authority — virtually assured that Hitler could thereafter constitutionally exercise dictatorial power without legal objection.

Hitler rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Being one of the best speakers of the party, he told the other members of the party to either make him leader of the party, or, he would never return. He was aided in part by his willingness to use violence in advancing his political objectives and to recruit party members who were willing to do the same. The Beer Hall putsch

in 1923 and the later release of his book Mein Kampf

(usually translated as My Struggle) introduced Hitler to a wider audience. In the mid-1920s, the party engaged in electoral battles in which Hitler participated as a speaker and organizer, as well as in street battles and violence between the Rotfrontkämpferbund

and the Nazi's Sturmabteilung

(SA). Through the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazis gathered enough electoral support to become the largest political party in the Reichstag

, and Hitler's blend of political acuity, deceptiveness and cunning converted the party's non-majority

but plurality status into effective governing power in the ailing Weimar Republic of 1933.

Once in power, the Nazis created a mythology surrounding the rise to power, and they described the period that roughly corresponds to the scope of this article as either the Kampfzeit (the time of struggle) or the Kampfjahre (years of struggle).

in World War I, on the Western Front

. Soon after the fighting on the front ended in November 1918, Hitler returned to Munich

after the Armistice

with no job, no real civilian job skills and no friends. He remained in the Reichswehr

and was given a relatively meaningless assignment during the winter of 1918-1919, but was eventually recruited by the Army's Political Department (Press and News Bureau), possibly because of his assistance to the Army in investigating the responsibility for the ill-fated Bavarian Soviet Republic

. Apparently his skills in oratory

, as well as his extreme and open anti-Semitism

, caught the eye of an approving army officer and he was promoted to an "education officer" — which gave him an opportunity to speak in public.

One of his duties was to report on "subversive" political groups, as ordered by his superiors. Any group which contained the word "Workers" in its name was certainly suspicious to the Political Department, and his commanders assigned Hitler, in his role as investigator, to attend a meeting of the small Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers' Party, abbreviated DAP) on 12 September 1919.

During the 12 September meeting, Hitler took umbrage with comments made by an audience member that were directed against Gottfried Feder

, the speaker, a crank economist with whom Hitler was acquainted as a result of a lecture Feder delivered in an Army "education" course. The audience member (Hitler in Mein Kampf disparagingly called him the "professor") asserted that Bavaria

should be wholly independent from Germany and should secede from Germany and unite with Austria

to form a new South German nation. The volatile Hitler arose and castigated the hapless "professor," employing his oratorical skills and eventually causing the "professor" to leave the meeting before its adjournment.

This bold (and typical) action by Hitler deeply impressed DAP founder Anton Drexler

, who promptly handed Hitler a political pamphlet. Soon, Drexler or his designate sent Hitler a postcard that invited him to join the party and to attend a "committee" meeting. Hitler attended this meeting, held at the Alte Rosenbad beer-house, and initially concluded that the party was too muddled and disorganized to merit further attention: It had neither membership numbers nor membership cards, and had a treasury of about seven Reichsmarks. However, on further reflection Hitler realized that because the party was neither well established nor particularly organized, he could exercise a greater influence on its direction. After two days in thought, Hitler decided to join the DAP; he was the party's fifty-fifth member.

Hitler's considerable talents were appreciated by the party leadership and in early 1920 he was named as its head of propaganda. Hitler's actions began to transform the party. On 20 February, the party added National Socialist (Nationalsozialistische) to its name and became the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP).

Four days later Feder and Hitler announced the party's 25-point program (see National Socialist Program

).

In August Hitler also organized a group of "security men" under the guise of a party "Gymnastics and Sports Division." The group was named at first the Ordnertruppen and it may well be that their principal intended purpose was, in fact, to keep order at Nazi meetings and to only suppress those who disrupted the Nazi meetings. In early October the group's name was officially changed to the Sturmabteilung

(Storm Detachment), which was certainly more descriptive and suggested the possibility of offensive, as well as solely defensive, action.

Throughout 1920, Hitler began to lecture at Munich's beer halls, particularly the Hofbräuhaus

, Sterneckerbräu and Bürgerbräukeller

. By this time, the police were already monitoring the speeches, and their own surviving records reveal that Hitler delivered lectures with titles such as Political Phenomenon, Jews

and the Treaty of Versailles

. At the end of the year, party membership was recorded at 2,000.

On 11 July 1921, Hitler resigned from the party after Drexler, the party's nominal leader, proposed merging the party into a larger Kampfbund

coalition. Hitler rejoined once the policy was abandoned, and on 28 July assumed control of the party by outcasting Drexler.

On 14 September 1921, Hitler and a substantial number of SA members and other Nazi party adherents disrupted a meeting at the Lowenbraukeller

of the Bavarian League. This federalist organization objected to the centralism of the Weimar Constitution, but accepted its social program. The League was led by Otto Ballerstedt, an engineer whom Hitler regarded as "my most dangerous opponent." One Nazi, Hermann Esser

, climbed upon a chair and shouted that the Jews were to blame for the misfortunes of Bavaria, and the Nazis shouted demands that Ballerstedt yield the floor to Hitler.

The Nazis beat up Ballerstedt and shoved him off the stage into the audience. Both Hitler and Esser were arrested, and Hitler commented notoriously to the police commissioner, "It's all right. We got what we wanted. Ballerstedt did not speak." Hitler was eventually sentenced to 3 months imprisonment and ended up serving only a little over one month.

On 4 November 1921, the Nazi Party held a large public meeting in the Munich Hofbräuhaus

. After Hitler had spoken for some time, the meeting erupted into a melee in which a small company of SA defeated the opposition.

, which would later become the Hitler Youth

. The other was the Stabswache, the first incarnation of what would later become the Schutzstaffeln (SS).

Inspired by Benito Mussolini

's March on Rome

Hitler decided that a coup d'état

was the proper strategy to seize control of the country. In May 1923, elements loyal to Hitler within the army helped the SA to procure a barracks and its weaponry, but the order to march never came.

A pivotal moment came when Hitler led the Beer Hall Putsch

, an attempted coup d'état on 8–9 November 1923. After it failed, Hitler was put on trial for treason, gaining great public attention.

In a rather spectacular trial in which Hitler endeavored to turn the tables and put democracy and the Weimar Republic on trial as traitors to the German people, he was convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment. He was eventually paroled, served only a little over eight months after his sentencing in early 1924. He was well-treated in prison, had a room with a view of the river, wore a tie, received visitors to his chambers and was permitted the use of a private secretary.

Hitler used the time in Landsberg prison

to consider his political strategy and dictate the first volume of Mein Kampf

, principally to his loyal aide Rudolf Hess

. After the putsch the party was banned in Bavaria

, but it participated in 1924's two elections by proxy as the National Socialist Freedom Movement

. In the German election, May 1924

the party gained seats in the Reichstag, with 6.55% (1,918,329) voting for the Movement. In the German election, December 1924

the National Socialist Freedom Movement (NSFB) (Combination of the Deutschvölkische Freiheitspartei (DVFP) and the Nazi Party (NSDAP)) lost 18 seats, only holding on to 14 seats, with 3% (907,242) of the electorate voting for Hitler's party.

The Barmat Scandal

was often used later in Nazi propaganda, both as an electoral strategy and as an appeal to anti-Semitism.

Hitler had determined, after some reflection, that power was to be achieved not through revolution outside of the government, but rather through legal means, within the confines of the democratic system established by Weimar.

For six years there would be no further prohibitions of the party (see below Seizure of Control: (1931-1933)).

the Party achieved just 12 seats (2.8% of the vote) in the Reichstag. The highest provincial gain was again in Bavaria (5.11%), though in three areas the NSDAP failed to gain even 1% of the vote. Overall the NSDAP gained 2.63% (810,127) of the vote. Partially due to the poor results, Hitler decided that Germans needed to know more about his goals. Despite being discouraged by his publisher, he wrote a second book that was discovered and released posthumously as Zweites Buch

. At this time the SA began a period of deliberate antagonism to the Rotfront by marching into Communist strongholds and starting violent altercations.

At the end of 1928, party membership was recorded at 130,000. In March 1929, Erich Ludendorff represented the Nazi party in the Presidential elections. He gained 280,000 votes (1.1%), and was the only candidate to poll fewer than a million votes. The battles on the streets grew increasingly violent. After the Rotfront interrupted a speech by Hitler, the SA marched into the streets of Nuremberg and killed two bystanders. In a tit-for-tat action, the SA stormed a Rotfront meeting on August 25 and days later the Berlin headquarters of the KPD itself. In September Goebbels

led his men into Neukölln

, a KPD stronghold, and the two warring parties exchanged pistol and revolver fire.

The German referendum of 1929

was important as it gained the Nazi Party recognition and credibility it never had before.

On 14 January 1930 Horst Wessel

got into an argument with his landlady — the Nazis said it was about rent, but the Communists alleged it was over Wessel's soliciting of prostitution on her premises — which would have fatal consequences. The landlady happened to be a member of the KPD, and contacted one of her Rotfront friends, Albert Hochter, who shot Wessel in the head at point-blank range. Wessel had penned a song months before his death, which would become Germany's national anthem for 12 years as the Horst-Wessel-Lied

. Goebbels also seized upon the attack (and the two weeks Wessel spent on his deathbed) to premier the song. The funeral was designed to be a propaganda opportunity for the Nazis, however the Rotfront stole Wessel's wreath and wrote "pimp" onto it. Along with Horst Wessel, the year 1930 resulted in more deaths in political violence than the previous two years combined.

On 1 April Hannover enacted a law banning the Hitlerjugend (the Hitler Youth

), and Goebbels was convicted of high treason at the end of May. Bavaria banned all political uniforms on 2 June, and on 11 June Prussia prohibited the wearing of SA brown shirts and associated insignia. The next month Prussia passed a law against its officials holding membership in either the NSDAP or KPD. Later in July, Goebbels was again tried, this time for "public insult", and fined. The government also placed the army officers on trial for "forming national socialist cells".

Against this violent backdrop, Hitler's party gained a shocking victory in the Reichstag, obtaining 107 seats (18.3%, 6,406,397 votes). The Nazis became the second largest party in Germany. In Bavaria the party gained 17.9% of the vote, though for the first time this percentage was exceeded by most other provinces: Oldenburg (27.3%), Braunschweig (26.6%), Waldeck (26.5%), Mecklenburg-Strelitz (22.6%), Lippe (22.3%) Mecklenburg-Schwerin (20.1%), Anhalt (19.8%), Thuringen (19.5%), Baden (19.2%), Hamburg (19.2%), Prussia (18.4%), Hessen (18.4%), Sachsen (18.3%), Lubeck (18.3%) and Schaumburg-Lippe (18.1%).

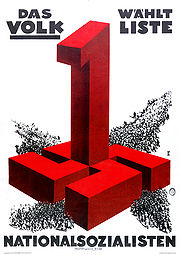

An unprecedented amount of money was thrown behind the campaign. Well over one million pamphlets were produced and distributed; sixty trucks were commandeered for use in Berlin alone. In areas where NSDAP campaigning was less rigorous, the total was as low as 9%. The Great Depression was also a factor in Hitler's electoral success. Against this legal backdrop, the SA began its first major anti-Jewish action on 13 October 1930 when groups of brownshirts smashed the windows of Jewish-owned stores at Potsdamer Platz

.

On March 10, 1931, with street violence between the Rotfront and SA spiraling out of control, breaking all previous barriers and expectations, Prussia

On March 10, 1931, with street violence between the Rotfront and SA spiraling out of control, breaking all previous barriers and expectations, Prussia

re-enacted its ban on brown shirts. Days after the ban SA-men shot dead two communists in a street fight, which led to a ban being placed on the public speaking of Goebbels, who side-stepped the prohibition by recording speeches and playing them to an audience in his absence.

Ernst Röhm

, in charge of the SA, put Count Micah von Helldorff, a convicted murderer and vehement anti-Semite, in charge of the Berlin SA. The deaths mounted up, with many more on the Rotfront side, and by the end of 1931 the SA suffered 47 deaths, and the Rotfront recorded losses of approximately 80. Street fights and beer hall battles resulting in deaths occurred throughout February and April 1932, all against the backdrop of Adolf Hitler's competition in the presidential election which pitted him against the monumentally popular Hindenburg. In the first round on 13 March, Hitler had polled over 11 million votes but was still behind Hindenburg. The second and final round took place on 10 April: Hitler (36.8% 13,418,547) lost out to Paul von Hindenburg

(53.0% 19,359,983) whilst KPD candidate Thälmann gained a meagre percentage of the vote (10.2% 3,706,759).

At this time, the Nazi party had just over 800,000 card-carrying members. Three days after the presidential elections, the German government passed the Law for the Maintenance of State Authority, which banned the NSDAP and its paramilitaries. This action was largely prompted by details which emerged at a trial of SA men for assaulting unarmed Jews in Berlin. But after less than a month the law was repealed by Franz von Papen

, Chancellor of Germany, on 30 May. Such ambivalence about the fate of Jews was supported by the culture of anti-Semitism that pervaded the German public at the time.

Dwarfed by Hitler's electoral gains, the KPD turned away from legal means and increasingly towards violence. One resulting battle in Silesia resulted in the army being dispatched, each shot sending Germany further into a potential all-out civil war. By this time both sides marched into each other's strongholds hoping to spark rivalry. Hermann Göring

, as speaker of the Reichstag, asked the Papen government to prosecute shooters. Laws were then passed which made political violence a capital crime.

The attacks continued, and reached fever pitch when SA storm leader Axel Schaffeld was assassinated. At the end of July, the Nazi party gained almost 14,000,000 votes, securing 230 seats in the Reichstag. Energised by the incredible results, Hitler asked to be made Chancellor. Papen offered the position of Vice Chancellor but Hitler refused.

Hermann Göring, in his position of Reichstag president, asked that decisive measures be taken by the government over the spate in murders of national socialists. On 9 August, amendments were made to the Reichstrafgesetzbuch statute on 'acts of political violence', increasing the penalty to 'lifetime imprisonment, 20 years hard labour or death'. Special courts were announced to try such offences. When in power less than half a year later, Hitler would use this legislation against his opponents with devastating effect.

The law was applied almost immediately but did not bring the perpetrators behind the recent massacres to trial as expected. Instead, five SA men who were alleged to have murdered a KPD member in Potempa (Upper Silesia

) were tried. Adolf Hitler appeared at the trial as a defence witness, but on 22 August the five were convicted and sentenced to death. On appeal, this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in early September. They would serve just over four months before Hitler freed all imprisoned Nazis in a 1933 amnesty.

The Nazi party lost 34 seats in the November 1932 election but remained the Reichstag's largest party. The most shocking move of the early election campaign was to send the SA to support a Rotfront action against the transport agency and in support of a strike.

After Chancellor Papen left office, he secretly told Hitler that he still held considerable sway with President Hindenburg and that he would make Hitler chancellor as long as he, Papen, could be the vice chancellor. On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of a coalition government of the NSDAP-DNVP Party. The SA and SS led torchlight parades throughout Berlin. In the coalition government, three members of the cabinet were Nazis: Hitler, Wilhelm Frick (Minister of the Interior) and Hermann Göring (Minister Without Portfolio).

With Germans who opposed Nazism failing to unite against it, Hitler soon moved to consolidate absolute power.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

joined the political party that was known as the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (abbreviated as DAP, and later commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). This political party was formed and developed during the post-World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

era. It was anti-Marxist and was opposed to the democratic post-war government of the Weimar Republic

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

and the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

; and it advocated extreme nationalism and Pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism

Pan-Germanism is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify the German-speaking populations of Europe in a single nation-state known as Großdeutschland , where "German-speaking" was taken to include the Low German, Frisian and Dutch-speaking populations of the Low...

as well as virulent anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

. Hitler's "rise" can be considered to have ended in March 1933, after the Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

adopted the Enabling Act of 1933 in that month; President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

had already appointed Hitler as Chancellor

Chancellor

Chancellor is the title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the Cancellarii of Roman courts of justice—ushers who sat at the cancelli or lattice work screens of a basilica or law court, which separated the judge and counsel from the...

on January 30, 1933 after a series of parliamentary elections and associated backstairs intrigues. The Enabling Act — when used ruthlessly and with authority — virtually assured that Hitler could thereafter constitutionally exercise dictatorial power without legal objection.

Hitler rose to a place of prominence in the early years of the party. Being one of the best speakers of the party, he told the other members of the party to either make him leader of the party, or, he would never return. He was aided in part by his willingness to use violence in advancing his political objectives and to recruit party members who were willing to do the same. The Beer Hall putsch

Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch was a failed attempt at revolution that occurred between the evening of 8 November and the early afternoon of 9 November 1923, when Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff, and other heads of the Kampfbund unsuccessfully tried to seize power...

in 1923 and the later release of his book Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf is a book written by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. It combines elements of autobiography with an exposition of Hitler's political ideology. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926...

(usually translated as My Struggle) introduced Hitler to a wider audience. In the mid-1920s, the party engaged in electoral battles in which Hitler participated as a speaker and organizer, as well as in street battles and violence between the Rotfrontkämpferbund

Rotfrontkämpferbund

Rotfrontkämpferbund was a paramilitary organization of the Communist Party of Germany created on 18 July 1924 during the Weimar Republic. Its first leader was Ernst Thälmann...

and the Nazi's Sturmabteilung

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

(SA). Through the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazis gathered enough electoral support to become the largest political party in the Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

, and Hitler's blend of political acuity, deceptiveness and cunning converted the party's non-majority

Majority

A majority is a subset of a group consisting of more than half of its members. This can be compared to a plurality, which is a subset larger than any other subset; i.e. a plurality is not necessarily a majority as the largest subset may consist of less than half the group's population...

but plurality status into effective governing power in the ailing Weimar Republic of 1933.

Once in power, the Nazis created a mythology surrounding the rise to power, and they described the period that roughly corresponds to the scope of this article as either the Kampfzeit (the time of struggle) or the Kampfjahre (years of struggle).

From Armistice (November 1918) to party membership (September 1919)

For over four years (August 1914 – November 1918), Germany was a principal belligerentBelligerent

A belligerent is an individual, group, country or other entity which acts in a hostile manner, such as engaging in combat. Belligerent comes from Latin, literally meaning "to wage war"...

in World War I, on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

. Soon after the fighting on the front ended in November 1918, Hitler returned to Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

after the Armistice

Armistice

An armistice is a situation in a war where the warring parties agree to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, but may be just a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace...

with no job, no real civilian job skills and no friends. He remained in the Reichswehr

Reichswehr

The Reichswehr formed the military organisation of Germany from 1919 until 1935, when it was renamed the Wehrmacht ....

and was given a relatively meaningless assignment during the winter of 1918-1919, but was eventually recruited by the Army's Political Department (Press and News Bureau), possibly because of his assistance to the Army in investigating the responsibility for the ill-fated Bavarian Soviet Republic

Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Munich Soviet Republic was, as part of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the short-lived attempt to establish a socialist state in form of a council republic in the Free State of Bavaria. It sought independence from the also recently proclaimed...

. Apparently his skills in oratory

Oratory

Oratory is a type of public speaking.Oratory may also refer to:* Oratory , a power metal band* Oratory , a place of worship* a religious order such as** Oratory of Saint Philip Neri ** Oratory of Jesus...

, as well as his extreme and open anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

, caught the eye of an approving army officer and he was promoted to an "education officer" — which gave him an opportunity to speak in public.

One of his duties was to report on "subversive" political groups, as ordered by his superiors. Any group which contained the word "Workers" in its name was certainly suspicious to the Political Department, and his commanders assigned Hitler, in his role as investigator, to attend a meeting of the small Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers' Party, abbreviated DAP) on 12 September 1919.

During the 12 September meeting, Hitler took umbrage with comments made by an audience member that were directed against Gottfried Feder

Gottfried Feder

Gottfried Feder was an economist and one of the early key members of the Nazi party. He was their economic theoretician. Initially, it was his lecture in 1919 that drew Hitler into the party.- Biography :...

, the speaker, a crank economist with whom Hitler was acquainted as a result of a lecture Feder delivered in an Army "education" course. The audience member (Hitler in Mein Kampf disparagingly called him the "professor") asserted that Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

should be wholly independent from Germany and should secede from Germany and unite with Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

to form a new South German nation. The volatile Hitler arose and castigated the hapless "professor," employing his oratorical skills and eventually causing the "professor" to leave the meeting before its adjournment.

This bold (and typical) action by Hitler deeply impressed DAP founder Anton Drexler

Anton Drexler

Anton Drexler was a German right-wing political leader of the 1920s, known for being Adolf Hitler's mentor during his early days in politics.-Biography:...

, who promptly handed Hitler a political pamphlet. Soon, Drexler or his designate sent Hitler a postcard that invited him to join the party and to attend a "committee" meeting. Hitler attended this meeting, held at the Alte Rosenbad beer-house, and initially concluded that the party was too muddled and disorganized to merit further attention: It had neither membership numbers nor membership cards, and had a treasury of about seven Reichsmarks. However, on further reflection Hitler realized that because the party was neither well established nor particularly organized, he could exercise a greater influence on its direction. After two days in thought, Hitler decided to join the DAP; he was the party's fifty-fifth member.

The first two years: party membership to the Hofbrauhaus Melee (November 1921)

By early 1920 the DAP had swelled to over 101 members, and Hitler received his membership card as member number 555 (the group started the counting at number 500).Hitler's considerable talents were appreciated by the party leadership and in early 1920 he was named as its head of propaganda. Hitler's actions began to transform the party. On 20 February, the party added National Socialist (Nationalsozialistische) to its name and became the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP).

Four days later Feder and Hitler announced the party's 25-point program (see National Socialist Program

National Socialist Program

The National Socialist Programme , was first, the political program of the German National Socialist Party in 1918, and later, in the 1920s, of the National Socialist German Workers' Party headed by Adolf...

).

In August Hitler also organized a group of "security men" under the guise of a party "Gymnastics and Sports Division." The group was named at first the Ordnertruppen and it may well be that their principal intended purpose was, in fact, to keep order at Nazi meetings and to only suppress those who disrupted the Nazi meetings. In early October the group's name was officially changed to the Sturmabteilung

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

(Storm Detachment), which was certainly more descriptive and suggested the possibility of offensive, as well as solely defensive, action.

Throughout 1920, Hitler began to lecture at Munich's beer halls, particularly the Hofbräuhaus

Hofbräuhaus

The Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München is a brewery in Munich, Germany, owned by the Bavarian state government...

, Sterneckerbräu and Bürgerbräukeller

Bürgerbräukeller

The Bürgerbräukeller was a large beer hall located in Munich, Germany. It was one of the large beer halls of the Bürgerliches Brauhaus company, and after Bürgerliches merged with Löwenbräu, the hall was transferred to that company. It was located on Rosenheimer Street in the neighborhood of...

. By this time, the police were already monitoring the speeches, and their own surviving records reveal that Hitler delivered lectures with titles such as Political Phenomenon, Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

and the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

. At the end of the year, party membership was recorded at 2,000.

On 11 July 1921, Hitler resigned from the party after Drexler, the party's nominal leader, proposed merging the party into a larger Kampfbund

Kampfbund

The Kampfbund was a league of patriotic fighting societies and the German National Socialist party in Bavaria, Germany, in the 1920s. It included Hitler's NSDAP party and their Sturmabteilung or SA for short, the Oberland League and the Reichskriegsflagge. Its military leader was Hermann Kriebel,...

coalition. Hitler rejoined once the policy was abandoned, and on 28 July assumed control of the party by outcasting Drexler.

On 14 September 1921, Hitler and a substantial number of SA members and other Nazi party adherents disrupted a meeting at the Lowenbraukeller

Löwenbräukeller

Löwenbräukeller is located in Maxvorstadt, Munich, Bavaria, Germany....

of the Bavarian League. This federalist organization objected to the centralism of the Weimar Constitution, but accepted its social program. The League was led by Otto Ballerstedt, an engineer whom Hitler regarded as "my most dangerous opponent." One Nazi, Hermann Esser

Hermann Esser

Hermann Esser entered the Nazi party with Adolf Hitler in 1920, became the editor of the Nazi paper, Völkischer Beobachter, and a Nazi member of the Reichstag. In the early history of the party, he was Hitler's de facto deputy.Esser was born in Röhrmoos, Kingdom of Bavaria...

, climbed upon a chair and shouted that the Jews were to blame for the misfortunes of Bavaria, and the Nazis shouted demands that Ballerstedt yield the floor to Hitler.

The Nazis beat up Ballerstedt and shoved him off the stage into the audience. Both Hitler and Esser were arrested, and Hitler commented notoriously to the police commissioner, "It's all right. We got what we wanted. Ballerstedt did not speak." Hitler was eventually sentenced to 3 months imprisonment and ended up serving only a little over one month.

On 4 November 1921, the Nazi Party held a large public meeting in the Munich Hofbräuhaus

Hofbräuhaus

The Staatliches Hofbräuhaus in München is a brewery in Munich, Germany, owned by the Bavarian state government...

. After Hitler had spoken for some time, the meeting erupted into a melee in which a small company of SA defeated the opposition.

From Beer Hall Melee to Beer Hall Coup D'État: the abortive Beer Hall Putsch and the ensuing trial

In the few months between the end of 1922 and the beginning of 1923, Hitler formed two organizations that would grow to have huge significance. The first was the Jungsturm and JugendbundJugendbund

The Jugendbund der NSDAP was a group similar to the Hitler Youth, and was indeed its predecessor. It was effectively the youth section of the Sturmabteilung and it existed between 1922 and 1923 when the NSDAP was banned following the failed Munich Putsch...

, which would later become the Hitler Youth

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party. It existed from 1922 to 1945. The HJ was the second oldest paramilitary Nazi group, founded one year after its adult counterpart, the Sturmabteilung...

. The other was the Stabswache, the first incarnation of what would later become the Schutzstaffeln (SS).

Inspired by Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

's March on Rome

March on Rome

The March on Rome was a march by which Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party came to power in the Kingdom of Italy...

Hitler decided that a coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

was the proper strategy to seize control of the country. In May 1923, elements loyal to Hitler within the army helped the SA to procure a barracks and its weaponry, but the order to march never came.

A pivotal moment came when Hitler led the Beer Hall Putsch

Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch was a failed attempt at revolution that occurred between the evening of 8 November and the early afternoon of 9 November 1923, when Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler, Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff, and other heads of the Kampfbund unsuccessfully tried to seize power...

, an attempted coup d'état on 8–9 November 1923. After it failed, Hitler was put on trial for treason, gaining great public attention.

In a rather spectacular trial in which Hitler endeavored to turn the tables and put democracy and the Weimar Republic on trial as traitors to the German people, he was convicted and sentenced to five years imprisonment. He was eventually paroled, served only a little over eight months after his sentencing in early 1924. He was well-treated in prison, had a room with a view of the river, wore a tie, received visitors to his chambers and was permitted the use of a private secretary.

Hitler used the time in Landsberg prison

Landsberg Prison

Landsberg Prison is a penal facility located in the town of Landsberg am Lech in the southwest of the German state of Bavaria, about west of Munich and south of Augsburg....

to consider his political strategy and dictate the first volume of Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf is a book written by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. It combines elements of autobiography with an exposition of Hitler's political ideology. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926...

, principally to his loyal aide Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess was a prominent Nazi politician who was Adolf Hitler's deputy in the Nazi Party during the 1930s and early 1940s...

. After the putsch the party was banned in Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

, but it participated in 1924's two elections by proxy as the National Socialist Freedom Movement

National Socialist Freedom Movement

The National Socialist Freedom Movement , or NSFB) or National Socialist Freedom Party was a German political party created in April 1924 in the aftermath of the Munich Putsch. Adolf Hitler and many Nazi Party leaders were jailed after the attempted coup and the Nazi party was outlawed in what...

. In the German election, May 1924

German election, May 1924

The German parliamentary federal elections, May 1924 in the Weimar Republic took place in 4 May 1924. They chose members for the republic's 2nd Reichstag.-Results:-References:...

the party gained seats in the Reichstag, with 6.55% (1,918,329) voting for the Movement. In the German election, December 1924

German election, December 1924

The German federal elections of 7 December 1924 was a parliamentary election in Weimar Republic Germany.-Results:...

the National Socialist Freedom Movement (NSFB) (Combination of the Deutschvölkische Freiheitspartei (DVFP) and the Nazi Party (NSDAP)) lost 18 seats, only holding on to 14 seats, with 3% (907,242) of the electorate voting for Hitler's party.

The Barmat Scandal

Barmat Scandal

The Barmat Scandal in 1924 and 1925 in Weimar Republic implicated the Social Democratic Party of Germany in Germany in charges of corruption, war profiteering, fraud, bribery and financial misdeeds. The scandal provided right-wing political forces within Germany with a basis with which to attack...

was often used later in Nazi propaganda, both as an electoral strategy and as an appeal to anti-Semitism.

Hitler had determined, after some reflection, that power was to be achieved not through revolution outside of the government, but rather through legal means, within the confines of the democratic system established by Weimar.

For six years there would be no further prohibitions of the party (see below Seizure of Control: (1931-1933)).

Move towards power (1925–1930)

In the German election, May 1928German election, 1928

The 1928, or 5th, federal election in Germany, which occurred on May 20, came one year after the ban on Adolf Hitler participating in political activities was officially lifted. As a result, the recently reformed Nazi Party was present in the elections. However, as the table below shows, the NSDAP...

the Party achieved just 12 seats (2.8% of the vote) in the Reichstag. The highest provincial gain was again in Bavaria (5.11%), though in three areas the NSDAP failed to gain even 1% of the vote. Overall the NSDAP gained 2.63% (810,127) of the vote. Partially due to the poor results, Hitler decided that Germans needed to know more about his goals. Despite being discouraged by his publisher, he wrote a second book that was discovered and released posthumously as Zweites Buch

Zweites Buch

The Zweites Buch is an unedited transcript of Adolf Hitler's thoughts on foreign policy written in 1928; it was written after Mein Kampf and was never published in his lifetime.-Composition:...

. At this time the SA began a period of deliberate antagonism to the Rotfront by marching into Communist strongholds and starting violent altercations.

At the end of 1928, party membership was recorded at 130,000. In March 1929, Erich Ludendorff represented the Nazi party in the Presidential elections. He gained 280,000 votes (1.1%), and was the only candidate to poll fewer than a million votes. The battles on the streets grew increasingly violent. After the Rotfront interrupted a speech by Hitler, the SA marched into the streets of Nuremberg and killed two bystanders. In a tit-for-tat action, the SA stormed a Rotfront meeting on August 25 and days later the Berlin headquarters of the KPD itself. In September Goebbels

Goebbels

Goebbels, alternatively Göbbels, is a common surname in the western areas of Germany. It is probably derived from the Old Low German word gibbler, meaning brewer...

led his men into Neukölln

Neukölln

Neukölln is the eighth borough of Berlin, located in the southeastern part of the city and was part of the former American sector under the Four-Power occupation of the city...

, a KPD stronghold, and the two warring parties exchanged pistol and revolver fire.

The German referendum of 1929

German referendum, 1929

The German referendum of 1929 was a failed attempt to introduce a 'Law against the Enslavement of the German People'. The law, proposed by German nationalists, would formally renounce the Treaty of Versailles and make it a criminal offence for German officials to co-operate in the collecting of...

was important as it gained the Nazi Party recognition and credibility it never had before.

On 14 January 1930 Horst Wessel

Horst Wessel

Horst Ludwig Wessel was a German Nazi activist who was made a posthumous hero of the Nazi movement following his violent death in 1930...

got into an argument with his landlady — the Nazis said it was about rent, but the Communists alleged it was over Wessel's soliciting of prostitution on her premises — which would have fatal consequences. The landlady happened to be a member of the KPD, and contacted one of her Rotfront friends, Albert Hochter, who shot Wessel in the head at point-blank range. Wessel had penned a song months before his death, which would become Germany's national anthem for 12 years as the Horst-Wessel-Lied

Horst-Wessel-Lied

The Horst-Wessel-Lied , also known as Die Fahne hoch from its opening line, was the anthem of the Nazi Party from 1930 to 1945...

. Goebbels also seized upon the attack (and the two weeks Wessel spent on his deathbed) to premier the song. The funeral was designed to be a propaganda opportunity for the Nazis, however the Rotfront stole Wessel's wreath and wrote "pimp" onto it. Along with Horst Wessel, the year 1930 resulted in more deaths in political violence than the previous two years combined.

On 1 April Hannover enacted a law banning the Hitlerjugend (the Hitler Youth

Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party. It existed from 1922 to 1945. The HJ was the second oldest paramilitary Nazi group, founded one year after its adult counterpart, the Sturmabteilung...

), and Goebbels was convicted of high treason at the end of May. Bavaria banned all political uniforms on 2 June, and on 11 June Prussia prohibited the wearing of SA brown shirts and associated insignia. The next month Prussia passed a law against its officials holding membership in either the NSDAP or KPD. Later in July, Goebbels was again tried, this time for "public insult", and fined. The government also placed the army officers on trial for "forming national socialist cells".

Against this violent backdrop, Hitler's party gained a shocking victory in the Reichstag, obtaining 107 seats (18.3%, 6,406,397 votes). The Nazis became the second largest party in Germany. In Bavaria the party gained 17.9% of the vote, though for the first time this percentage was exceeded by most other provinces: Oldenburg (27.3%), Braunschweig (26.6%), Waldeck (26.5%), Mecklenburg-Strelitz (22.6%), Lippe (22.3%) Mecklenburg-Schwerin (20.1%), Anhalt (19.8%), Thuringen (19.5%), Baden (19.2%), Hamburg (19.2%), Prussia (18.4%), Hessen (18.4%), Sachsen (18.3%), Lubeck (18.3%) and Schaumburg-Lippe (18.1%).

An unprecedented amount of money was thrown behind the campaign. Well over one million pamphlets were produced and distributed; sixty trucks were commandeered for use in Berlin alone. In areas where NSDAP campaigning was less rigorous, the total was as low as 9%. The Great Depression was also a factor in Hitler's electoral success. Against this legal backdrop, the SA began its first major anti-Jewish action on 13 October 1930 when groups of brownshirts smashed the windows of Jewish-owned stores at Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz is an important public square and traffic intersection in the centre of Berlin, Germany, lying about one kilometre south of the Brandenburg Gate and the Reichstag , and close to the southeast corner of the Tiergarten park...

.

Seizure of control (1931–1933)

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

re-enacted its ban on brown shirts. Days after the ban SA-men shot dead two communists in a street fight, which led to a ban being placed on the public speaking of Goebbels, who side-stepped the prohibition by recording speeches and playing them to an audience in his absence.

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Röhm, was a German officer in the Bavarian Army and later an early Nazi leader. He was a co-founder of the Sturmabteilung , the Nazi Party militia, and later was its commander...

, in charge of the SA, put Count Micah von Helldorff, a convicted murderer and vehement anti-Semite, in charge of the Berlin SA. The deaths mounted up, with many more on the Rotfront side, and by the end of 1931 the SA suffered 47 deaths, and the Rotfront recorded losses of approximately 80. Street fights and beer hall battles resulting in deaths occurred throughout February and April 1932, all against the backdrop of Adolf Hitler's competition in the presidential election which pitted him against the monumentally popular Hindenburg. In the first round on 13 March, Hitler had polled over 11 million votes but was still behind Hindenburg. The second and final round took place on 10 April: Hitler (36.8% 13,418,547) lost out to Paul von Hindenburg

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

(53.0% 19,359,983) whilst KPD candidate Thälmann gained a meagre percentage of the vote (10.2% 3,706,759).

At this time, the Nazi party had just over 800,000 card-carrying members. Three days after the presidential elections, the German government passed the Law for the Maintenance of State Authority, which banned the NSDAP and its paramilitaries. This action was largely prompted by details which emerged at a trial of SA men for assaulting unarmed Jews in Berlin. But after less than a month the law was repealed by Franz von Papen

Franz von Papen

Lieutenant-Colonel Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen zu Köningen was a German nobleman, Roman Catholic monarchist politician, General Staff officer, and diplomat, who served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932 and as Vice-Chancellor under Adolf Hitler in 1933–1934...

, Chancellor of Germany, on 30 May. Such ambivalence about the fate of Jews was supported by the culture of anti-Semitism that pervaded the German public at the time.

Dwarfed by Hitler's electoral gains, the KPD turned away from legal means and increasingly towards violence. One resulting battle in Silesia resulted in the army being dispatched, each shot sending Germany further into a potential all-out civil war. By this time both sides marched into each other's strongholds hoping to spark rivalry. Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

, as speaker of the Reichstag, asked the Papen government to prosecute shooters. Laws were then passed which made political violence a capital crime.

The attacks continued, and reached fever pitch when SA storm leader Axel Schaffeld was assassinated. At the end of July, the Nazi party gained almost 14,000,000 votes, securing 230 seats in the Reichstag. Energised by the incredible results, Hitler asked to be made Chancellor. Papen offered the position of Vice Chancellor but Hitler refused.

Hermann Göring, in his position of Reichstag president, asked that decisive measures be taken by the government over the spate in murders of national socialists. On 9 August, amendments were made to the Reichstrafgesetzbuch statute on 'acts of political violence', increasing the penalty to 'lifetime imprisonment, 20 years hard labour or death'. Special courts were announced to try such offences. When in power less than half a year later, Hitler would use this legislation against his opponents with devastating effect.

The law was applied almost immediately but did not bring the perpetrators behind the recent massacres to trial as expected. Instead, five SA men who were alleged to have murdered a KPD member in Potempa (Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

) were tried. Adolf Hitler appeared at the trial as a defence witness, but on 22 August the five were convicted and sentenced to death. On appeal, this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in early September. They would serve just over four months before Hitler freed all imprisoned Nazis in a 1933 amnesty.

The Nazi party lost 34 seats in the November 1932 election but remained the Reichstag's largest party. The most shocking move of the early election campaign was to send the SA to support a Rotfront action against the transport agency and in support of a strike.

After Chancellor Papen left office, he secretly told Hitler that he still held considerable sway with President Hindenburg and that he would make Hitler chancellor as long as he, Papen, could be the vice chancellor. On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of a coalition government of the NSDAP-DNVP Party. The SA and SS led torchlight parades throughout Berlin. In the coalition government, three members of the cabinet were Nazis: Hitler, Wilhelm Frick (Minister of the Interior) and Hermann Göring (Minister Without Portfolio).

With Germans who opposed Nazism failing to unite against it, Hitler soon moved to consolidate absolute power.

See also

- MachtergreifungMachtergreifungMachtergreifung is a German word meaning "seizure of power". It is normally used specifically to refer to the Nazi takeover of power in the democratic Weimar Republic on 30 January 1933, the day Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany, turning it into the Nazi German dictatorship.-Term:The...

- GleichschaltungGleichschaltungGleichschaltung , meaning "coordination", "making the same", "bringing into line", is a Nazi term for the process by which the Nazi regime successively established a system of totalitarian control and tight coordination over all aspects of society. The historian Richard J...

- Night of the Long KnivesNight of the Long KnivesThe Night of the Long Knives , sometimes called "Operation Hummingbird " or in Germany the "Röhm-Putsch," was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany between June 30 and July 2, 1934, when the Nazi regime carried out a series of political murders...

- Early Nazi TimelineEarly Nazi TimelineThe early timeline of Nazism begins with its origins in 1896 and continues until Hitler's rise to power.- Prehistory of National Socialism :*1834 the term "Nationalsozialismus" first appears in Print: Börsenblatt für den deutschen Buchhandel, page 36...

- Weimar paramilitary groupsWeimar paramilitary groupsParamilitary groups were formed throughout the Weimar Republic in the wake of Germany's defeat in World War I and the ensuing German Revolution. Some were created by political parties to help in recruiting, discipline and in preparation for seizing power. Some were created before World War I....

- Weimar political partiesWeimar political partiesThe Weimar Republic was in existence for thirteen years. In that time, some 40 parties were represented in the Reichstag. This fragmentation of political power was in part due to the peculiar parliamentary system of the Weimar Republic, and in part due to the many challenges facing German democracy...

- Poison KitchenPoison KitchenThe Poison Kitchen was the name Adolf Hitler gave to a group of journalists of the Bavarian newspaper The Munich Post who were highly critical of Hitler and ran a series of extremely negative investigative exposés about Hitler in the 1920s and early 1930s, before Hitler came to power in Germany in...

External links

- Hitler becomes Chancellor Original reports from The Times