Gyro Monorail

Encyclopedia

Gyrocar

A gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself...

are terms for a single rail

Rail profile

The rail profile is the cross sectional shape of a railway rail, perpendicular to the length of the rail.In all but very early cast iron rails, a rail is hot rolled steel of a specific cross sectional profile designed for use as the fundamental component of railway track.Unlike some other uses of...

land vehicle that uses the gyroscopic

Gyroscope

A gyroscope is a device for measuring or maintaining orientation, based on the principles of angular momentum. In essence, a mechanical gyroscope is a spinning wheel or disk whose axle is free to take any orientation...

action of a spinning

Rotation

A rotation is a circular movement of an object around a center of rotation. A three-dimensional object rotates always around an imaginary line called a rotation axis. If the axis is within the body, and passes through its center of mass the body is said to rotate upon itself, or spin. A rotation...

wheel, to overcome the inherent instability

Mechanical equilibrium

A standard definition of static equilibrium is:This is a strict definition, and often the term "static equilibrium" is used in a more relaxed manner interchangeably with "mechanical equilibrium", as defined next....

of balancing on top of a single rail.

The monorail is associated with the names Louis Brennan

Louis Brennan

Louis Brennan was an Irish-Australian mechanical engineer and inventor.Brennan was born in Castlebar, Ireland, and moved to Melbourne, Australia in 1861 with parents...

, August Scherl

August Scherl

August Scherl, a German newspaper magnate, was born on 24 July 1849 in Düsseldorf, and died on 18 April 1921 in Berlin.August Hugo Friedrich Scherl founded a newspaper and publishing concern on 1 October 1883, which from 1900 carried the name August Scherl Verlag.He was editor of the Berlin Local...

and Pyotr Shilovsky

Pyotr Shilovsky

Pyotr Petrovich Shilovsky was a Russian count, jurist, statesman, governor of Kostroma in 1910-1912 and of Olonets Governorate in 1912-1913, best known as inventor of gyrocar, which he demonstrated for the first time in London in 1914. After October Revolution Shilovsky emigrated to United...

, who each built full-scale working prototype

Prototype

A prototype is an early sample or model built to test a concept or process or to act as a thing to be replicated or learned from.The word prototype derives from the Greek πρωτότυπον , "primitive form", neutral of πρωτότυπος , "original, primitive", from πρῶτος , "first" and τύπος ,...

s during the early part of the twentieth century. A version was developed by Ernest F. Swinney, Harry Ferreira and Louis E. Swinney in the USA in 1962.

The gyro monorail has never developed beyond the prototype stage.

The principal advantage of the monorail cited by Shilovsky is the suppression of hunting oscillation

Hunting oscillation

Hunting oscillation is an oscillation, usually unwanted, about an equilibrium. The expression came into use in the 19th century and describes how a systems 'hunts' for equilibrium...

, a speed limitation encountered by conventional railways at the time. Also, sharper turns are possible compared to the 7 km typical of modern high-speed trains such as the TGV, because the vehicle will bank automatically on bends, like an aircraft, so that no lateral centrifugal acceleration is experienced on board.

A major drawback is that many cars - including passenger and freight cars, not just the locomotive - would require a constantly powered gyroscope to stay upright.

Unlike other means of maintaining balance, such as lateral shifting of the centre of gravity or the use of reaction wheels, the gyroscopic balancing system is statically stable, so that the control system serves only to impart dynamic stability. The active part of the balancing system is therefore more accurately described as a roll damper.

Brennan's monorail

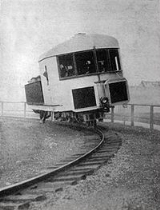

The image in the leader section depicts the 22 tonneTonne

The tonne, known as the metric ton in the US , often put pleonastically as "metric tonne" to avoid confusion with ton, is a metric system unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. The tonne is not an International System of Units unit, but is accepted for use with the SI...

(unladen weight) prototype vehicle developed by Louis Philip Brennan CB

Louis Brennan

Louis Brennan was an Irish-Australian mechanical engineer and inventor.Brennan was born in Castlebar, Ireland, and moved to Melbourne, Australia in 1861 with parents...

. Brennan filed his first monorail patent in 1903.

His first demonstration model was just a 2 ft 6in by 12 inch (762 mm by 300 mm) box containing the balancing system. However, this was sufficient for the Army Council to recommend a sum of £10,000 for the development of a full size vehicle. This was vetoed by their Financial Department. However, the Army found £2000 from various sources to fund Brennan's work.

Within this budget Brennan produced a larger model, 6 ft (1.83m) long by 1 ft 6in (0.46m) wide, kept in balance by two 5 inch (127 mm) diameter gyroscope rotors. This model is still in existence in the London Science Museum. The track for the vehicle was laid in the grounds of Brennan's house in Gillingham, Kent

Gillingham, Kent

Gillingham is a town in the unitary authority of Medway in South East England. It is part of the ceremonial county of Kent. The town includes the settlements of Brompton, Hempstead, Rainham, Rainham Mark and Twydall....

. It consisted of ordinary gas piping laid on wooden sleepers, with a fifty foot wire rope bridge, sharp corners and slope

Slope

In mathematics, the slope or gradient of a line describes its steepness, incline, or grade. A higher slope value indicates a steeper incline....

s up to one in five.

War Department (UK)

The War Department was the United Kingdom government department responsible for the supply of equipment to the armed forces of the United Kingdom and the pursuance of military activity. In 1857 it became the War Office...

's initial enthusiasm. However, the election in 1906 of a Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

government, with policies of financial retrenchment, effectively stopped the funding from the Army. However, the India Office

India Office

The India Office was a British government department created in 1858 to oversee the colonial administration of India, i.e. the modern-day nations of Bangladesh, Burma, India, and Pakistan, as well as territories in South-east and Central Asia, the Middle East, and parts of the east coast of Africa...

voted an advance of £6000 in 1907 to develop the monorail for the North West Frontier region, and a further £5000 was advanced by the Durbar of Kashmir in 1908. This money was almost spent by January 1909, when the India Office advanced a further £2000.

On 15 October 1909, the railcar

Railcar

A railcar, in British English and Australian English, is a self-propelled railway vehicle designed to transport passengers. The term "railcar" is usually used in reference to a train consisting of a single coach , with a driver's cab at one or both ends. Some railways, e.g., the Great Western...

ran under its own power for the first time, carrying 32 people around the factory. The vehicle was 40 ft (12.2m) long and 10 ft (3m) wide, and with a 20 hp (15 kW) petrol engine

Petrol engine

A petrol engine is an internal combustion engine with spark-ignition, designed to run on petrol and similar volatile fuels....

, had a speed

Speed

In kinematics, the speed of an object is the magnitude of its velocity ; it is thus a scalar quantity. The average speed of an object in an interval of time is the distance traveled by the object divided by the duration of the interval; the instantaneous speed is the limit of the average speed as...

of 22 mph (35 km/h). The transmission

Transmission (mechanics)

A machine consists of a power source and a power transmission system, which provides controlled application of the power. Merriam-Webster defines transmission as: an assembly of parts including the speed-changing gears and the propeller shaft by which the power is transmitted from an engine to a...

was electric, with the petrol engine driving a generator

Electrical generator

In electricity generation, an electric generator is a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy. A generator forces electric charge to flow through an external electrical circuit. It is analogous to a water pump, which causes water to flow...

, and electric motors located on both bogie

Bogie

A bogie is a wheeled wagon or trolley. In mechanics terms, a bogie is a chassis or framework carrying wheels, attached to a vehicle. It can be fixed in place, as on a cargo truck, mounted on a swivel, as on a railway carriage/car or locomotive, or sprung as in the suspension of a caterpillar...

s. This generator also supplied power to the gyro motors and the air compressor

Air compressor

An air compressor is a device that converts power into kinetic energy by compressing and pressurizing air, which, on command, can be released in quick bursts...

. The balancing system used a pneumatic servo

Servomechanism

thumb|right|200px|Industrial servomotorThe grey/green cylinder is the [[Brush |brush-type]] [[DC motor]]. The black section at the bottom contains the [[Epicyclic gearing|planetary]] [[Reduction drive|reduction gear]], and the black object on top of the motor is the optical [[rotary encoder]] for...

, rather than the friction wheel

Friction drive

A friction Drive or friction engine is a type of transmission that, instead of a chain and sprockets, uses 2 wheels in the transmission to transfer power to the driving wheels. This kind of transmission is often used on scooters, mainly go-peds, in place of a chain.An example of this system is in...

s used in the earlier model.

The gyros were located in the cab, although Brennan planned to re-site them under the floor of the vehicle before displaying the vehicle in public, but the unveiling of Scherl's machine forced him to bring forward the first public demonstration to 10 November 1909. There was insufficient time to re-position the gyros before the monorail's public debut.

The real public debut for Brennan's monorail was the Japan-British Exhibition at the White City

White City, London

White City is a district in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, to the north of Shepherd's Bush. Today, White City is home to the BBC Television Centre and BBC White City, and Loftus Road stadium, the home of football club Queens Park Rangers FC....

, London in 1910. The monorail car carried 50 passengers at a time around a circular track at 20 mph. Passengers included Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, who showed considerable enthusiasm. Although a viable means of transport, the monorail failed to attract further investment. Of the two vehicles built, one was sold as scrap, and the other was used as a park shelter until 1930.

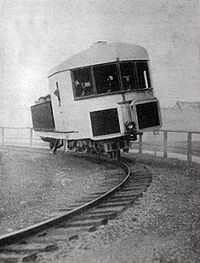

Scherl's car

Just as Brennan completed testing his vehicle, August ScherlAugust Scherl

August Scherl, a German newspaper magnate, was born on 24 July 1849 in Düsseldorf, and died on 18 April 1921 in Berlin.August Hugo Friedrich Scherl founded a newspaper and publishing concern on 1 October 1883, which from 1900 carried the name August Scherl Verlag.He was editor of the Berlin Local...

, a German publisher and philanthropist

Philanthropist

A philanthropist is someone who engages in philanthropy; that is, someone who donates his or her time, money, and/or reputation to charitable causes...

, announced a public demonstration of the gyro monorail which he had developed in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. The demonstration was to take place on Wednesday 10 November 1909 at the Berlin Zoological Gardens.

Servomechanism

thumb|right|200px|Industrial servomotorThe grey/green cylinder is the [[Brush |brush-type]] [[DC motor]]. The black section at the bottom contains the [[Epicyclic gearing|planetary]] [[Reduction drive|reduction gear]], and the black object on top of the motor is the optical [[rotary encoder]] for...

was hydraulic, and propulsion

Ground propulsion

Ground propulsion is a different term than transport, because it refers to solid bodies being propelled. Those bodies may be mounted on vats or using wheels while the latter dominates for standard applications....

electric. Strictly speaking, August Scherl merely provided the financial backing. The righting mechanism was invented by Paul Fröhlich, and the car designed by Emil Falcke.

Although well received and performing perfectly during its public demonstrations, the car failed to attract significant financial support, and Scherl wrote off his investment in it.

Shilovsky's work

Following the failure of Brennan and Scherl to attract the necessary investment, the practical development of the gyro-monorail after 1910 continued with the work of Pyotr ShilovskyPyotr Shilovsky

Pyotr Petrovich Shilovsky was a Russian count, jurist, statesman, governor of Kostroma in 1910-1912 and of Olonets Governorate in 1912-1913, best known as inventor of gyrocar, which he demonstrated for the first time in London in 1914. After October Revolution Shilovsky emigrated to United...

, a Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n aristocrat

Aristocracy (class)

The aristocracy are people considered to be in the highest social class in a society which has or once had a political system of Aristocracy. Aristocrats possess hereditary titles granted by a monarch, which once granted them feudal or legal privileges, or deriving, as in Ancient Greece and India,...

residing in London. His balancing system was based on slightly different principles to those of Brennan and Scherl, and permitted the use of a smaller, more slowly spinning gyroscope. After developing a model gyro monorail in 1911, he designed a gyrocar

Gyrocar

A gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself...

which was built by the Wolseley Motor Company

Wolseley Motor Company

The Wolseley Motor Company was a British automobile manufacturer founded in 1901. After 1935 it was incorporated into larger companies but the Wolseley name remained as an upmarket marque until 1975.-History:...

and tested on the streets of London in 1913. Since it used a single gyro, rather than the counter-rotating pair favoured by Brennan and Scherl, it exhibited asymmetry

Asymmetry

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry.-In organisms:Due to how cells divide in organisms, asymmetry in organisms is fairly usual in at least one dimension, with biological symmetry also being common in at least one dimension....

in its behaviour, and became unstable during sharp left hand turns. It attracted interest but no serious funding.

Post-World War I developments

In 1922 the Soviet government began construction of a Shilovsky monorail between LeningradLeningrad

Leningrad is the former name of Saint Petersburg, Russia.Leningrad may also refer to:- Places :* Leningrad Oblast, a federal subject of Russia, around Saint Petersburg* Leningrad, Tajikistan, capital of Muminobod district in Khatlon Province...

and Tsarskoe Selo, but funds ran out shortly after the project was begun.

In 1929, at the age of 74, Brennan also developed a gyrocar. This was turned down by a consortium of Austin

Austin Motor Company

The Austin Motor Company was a British manufacturer of automobiles. The company was founded in 1905 and merged in 1952 into the British Motor Corporation Ltd. The marque Austin was used until 1987...

/Morris

Morris Motor Company

The Morris Motor Company was a British car manufacturing company. After the incorporation of the company into larger corporations, the Morris name remained in use as a marque until 1984 when British Leyland's Austin Rover Group decided to concentrate on the more popular Austin marque...

/Rover

Rover (car)

The Rover Company is a former British car manufacturing company founded as Starley & Sutton Co. of Coventry in 1878. After developing the template for the modern bicycle with its Rover Safety Bicycle of 1885, the company moved into the automotive industry...

, on the basis that they could sell all the conventional cars they built.

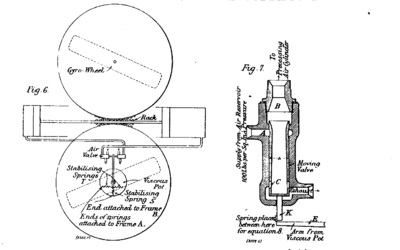

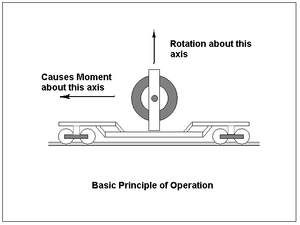

Basic idea

The vehicle runs on a single conventional rail, so that without the balancing system it would topple over.

Gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that allows the rotation of an object about a single axis. A set of two gimbals, one mounted on the other with pivot axes orthogonal, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain immobile regardless of the motion of its support...

frame whose axis of rotation (the precession axis) is perpendicular

Perpendicular

In geometry, two lines or planes are considered perpendicular to each other if they form congruent adjacent angles . The term may be used as a noun or adjective...

to the spin axis. The assembly is mounted on the vehicle chassis

Chassis

A chassis consists of an internal framework that supports a man-made object. It is analogous to an animal's skeleton. An example of a chassis is the underpart of a motor vehicle, consisting of the frame with the wheels and machinery.- Vehicles :In the case of vehicles, the term chassis means the...

such that, at equilibrium

Mechanical equilibrium

A standard definition of static equilibrium is:This is a strict definition, and often the term "static equilibrium" is used in a more relaxed manner interchangeably with "mechanical equilibrium", as defined next....

, the spin axis, precession axis and vehicle roll axis are mutually perpendicular.

Forcing the gimbal to rotate causes the wheel to precess resulting in gyroscopic torque

Torque

Torque, moment or moment of force , is the tendency of a force to rotate an object about an axis, fulcrum, or pivot. Just as a force is a push or a pull, a torque can be thought of as a twist....

s about the roll axis, so that the mechanism has the potential to right the vehicle when tilted from the vertical

Vertical direction

In astronomy, geography, geometry and related sciences and contexts, a direction passing by a given point is said to be vertical if it is locally aligned with the gradient of the gravity field, i.e., with the direction of the gravitational force at that point...

. The wheel shows a tendency to align its spin axis with the axis of rotation (the gimbal axis), and it is this action which rotates the entire vehicle about its roll axis.

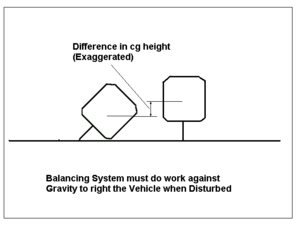

Ideally, the mechanism applying control torques to the gimbal ought to be passive (an arrangement of spring

Spring (device)

A spring is an elastic object used to store mechanical energy. Springs are usually made out of spring steel. Small springs can be wound from pre-hardened stock, while larger ones are made from annealed steel and hardened after fabrication...

s, damper

Dashpot

A dashpot is a mechanical device, a damper which resists motion via viscous friction. The resulting force is proportional to the velocity, but acts in the opposite direction, slowing the motion and absorbing energy. It is commonly used in conjunction with a spring...

s and lever

Lever

In physics, a lever is a rigid object that is used with an appropriate fulcrum or pivot point to either multiply the mechanical force that can be applied to another object or resistance force , or multiply the distance and speed at which the opposite end of the rigid object travels.This leverage...

s), but the fundamental nature of the problem indicates that this would be impossible. The equilibrium position is with the vehicle upright, so that any disturbance from this position reduces the height of the centre of gravity, lowering the potential energy

Potential energy

In physics, potential energy is the energy stored in a body or in a system due to its position in a force field or due to its configuration. The SI unit of measure for energy and work is the Joule...

of the system. Whatever returns the vehicle to equilibrium must be capable of restoring this potential energy, and hence cannot consist of passive elements alone. The system must contain an active servo

Servomechanism

thumb|right|200px|Industrial servomotorThe grey/green cylinder is the [[Brush |brush-type]] [[DC motor]]. The black section at the bottom contains the [[Epicyclic gearing|planetary]] [[Reduction drive|reduction gear]], and the black object on top of the motor is the optical [[rotary encoder]] for...

of some kind.

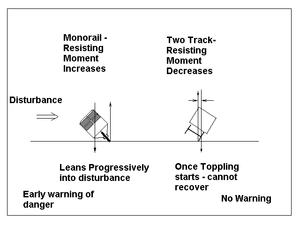

Side loads

If constant side forces were resisted by gyroscopic action alone, the gimbal would rotate quickly on to the stops, and the vehicle would topple. In fact, the mechanism causes the vehicle to lean into the disturbance, resisting it with a component of weight, with the gyro near its undeflected position.Inertial side forces, arising from cornering, cause the vehicle to lean into the corner. A single gyro introduces an asymmetry

Asymmetry

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry.-In organisms:Due to how cells divide in organisms, asymmetry in organisms is fairly usual in at least one dimension, with biological symmetry also being common in at least one dimension....

which will cause the vehicle to lean too far, or not far enough for the net force to remain in the plane of symmetry, so side forces will still be experienced on board.

In order to ensure that the vehicle bank

Flight dynamics

Flight dynamics is the science of air vehicle orientation and control in three dimensions. The three critical flight dynamics parameters are the angles of rotation in three dimensions about the vehicle's center of mass, known as pitch, roll and yaw .Aerospace engineers develop control systems for...

s correctly on corners, it is necessary to remove the gyroscopic torque arising from the vehicle rate of turn

Turn

Turn may refer to:In music:* Turn , a sequence of several notes next to each other in the scale* Turn , an Irish rock group* Turn LP, a 2005 rock album by Turn* Turn , a 2004 punk album by The Ex...

.

A free gyro keeps its orientation with respect to inertial space

Inertial space

In physics, the expression inertial space refers to the background reference that is provided by the phenomenon of inertia.Inertia is opposition to change of velocity, that is: change of velocity with respect to the background, the background that all physical objects are embedded in....

, and gyroscopic moments are generated by rotating it about an axis perpendicular to the spin axis. But the control system

Control system

A control system is a device, or set of devices to manage, command, direct or regulate the behavior of other devices or system.There are two common classes of control systems, with many variations and combinations: logic or sequential controls, and feedback or linear controls...

deflects the gyro with respect to the chassis

Chassis

A chassis consists of an internal framework that supports a man-made object. It is analogous to an animal's skeleton. An example of a chassis is the underpart of a motor vehicle, consisting of the frame with the wheels and machinery.- Vehicles :In the case of vehicles, the term chassis means the...

, and not with respect to the fixed stars. It follows that the pitch and yaw motion of the vehicle with respect to inertial space will introduce additional unwanted, gyroscopic torques. These give rise to unsatisfactory equilibria, but more seriously, cause a loss of static stability when turning in one direction, and an increase in static stability in the opposite direction. Shilovsky encountered this problem with his road vehicle, which consequently could not make sharp left hand turns.

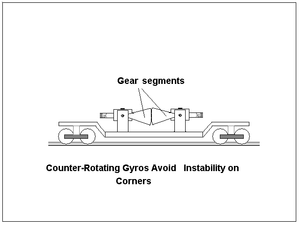

Brennan and Scherl were aware of this problem, and implemented their balancing systems with pairs of counter rotating gyros, precessing in opposite directions. With this arrangement, all motion of the vehicle with respect to inertial space causes equal and opposite torques on the two gyros, and are consequently cancelled out. With the double gyro system, the instability on bends is eliminated and the vehicle will bank to the correct angle, so that no net side force is experienced on board.

Offset loads similarly cause the vehicle to lean until the centre of gravity lies above the support point. Side winds cause the vehicle to tilt into them, to resist them with a component of weight. These contact forces are likely to cause more discomfort than cornering forces, because they will result in net side forces being experienced on board.

The contact side forces result in a gimbal deflection bias

Bias

Bias is an inclination to present or hold a partial perspective at the expense of alternatives. Bias can come in many forms.-In judgement and decision making:...

in a Shilovsky loop. This may be used as an input to a slower loop to shift the centre of gravity laterally, so that the vehicle remains upright in the presence of sustained non-inertial forces. This combination of gyro and lateral cg shift is the subject of a 1962 patent. A vehicle using a gyro/lateral payload

Cargo

Cargo is goods or produce transported, generally for commercial gain, by ship, aircraft, train, van or truck. In modern times, containers are used in most intermodal long-haul cargo transport.-Marine:...

shift was built by Ernest F. Swinney, Harry Ferreira and Louis E. Swinney in the USA in 1962. This system is called the Gyro-Dynamics monorail.

Potential advantages over two-track vehicles

The advantages of the monorail over conventional railways were summarised by Shilovsky. The following have been claimed.Universal gauge tracks

Different countries use different gauges (widths) of tracks, so the logistics get rather problematic for trains that travel to different countries with different gauges, i.e. trains need to transfer cargo, change axles, or some similar time and money-consuming task must be performed. A single-rail track should eliminate these problems and hence simplify international rail transport.Reduced right-of-way problem

The close association of the vehicle with its single rail, its inherent ability to bank on bends, and the reduced reliance on adhesion forces are all factors which are pertinent to the development of surface travel. In principle, steeper gradients and sharper corners may be negotiated compared with a conventional adhesion railway. Typical high speed train designs have radius of turn of 7 km, with consequently few options for new routes within developed countries, where almost all of the land is under individual or corporate ownership.In his book, Shilovsky describes a form of on-track braking, which is feasible with a monorail, but would upset the directional stability of a conventional rail vehicle. This has the potential of much shorter stopping distances compared with conventional wheel on steel, with a corresponding reduction in safe separation between trains. The result is potentially higher occupancy of the track, and higher capacity.

Reduced total system cost

While the individual vehicles are likely to be expensive, the greatest cost arises from the construction and maintenance of the permanent way, which, for a single rail at ground level must be cheaper.Benign failure modes

The angular momentum in the gyros is so high that loss of power will not present a hazard for a good half hour in a well designed system.

Reduced weight

Shilovsky claimed his designs were actually lighter than the equivalent duo-rail vehicles. The gyro mass, according to Brennan, accounts for 3-5% of the vehicle weight, which is comparable to the bogie weight saved in using a single track design.Potential for high speed

High speed conventionally requires straight track, introducing a right of way problem in developed countries. Wheel profiles which permit sharp cornering tend to encounter the classical hunting oscillationHunting oscillation

Hunting oscillation is an oscillation, usually unwanted, about an equilibrium. The expression came into use in the 19th century and describes how a systems 'hunts' for equilibrium...

at low speeds. Running on a single rail is an effective means to suppress hunting.

Turning corners

acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

acting about the gimbal pivot, so that an additional gyroscopic moment is introduced into the roll equation:

This displaces the roll from the correct bank angle for the turn, but more seriously, changes the constant term in the characteristic equation to:

Evidently, if the turn rate exceeds a critical value:

The balancing loop will become unstable.

However, an identical gyro spinning in the opposite sense will cancel the roll torque which is causing the instability, and if it is forced to precess in the opposite direction to the first gyro will produce a control torque in the same direction.

In 1972, the Canadian Government's Division of Mechanical Engineering rejected a monorail proposal largely on the basis of this problem. Their analysis was correct, but restricted in scope to single vertical axis gyro systems, and not universal.

Maximum spin rate

Gas turbine engines are designed with peripheral speeds as high as 400 m/s, and have operated reliably on thousands of aircraft over the past 50 years. Hence, an estimate of the gyro mass for a 10 tonne vehicle, with cg height at 2m, assuming a peripheral speed of half what is used in jet engine design, is a mere 140 kg. Brennan's recommendation of 3-5% of the vehicle mass was therefore highly conservative.See also

- Adhesion railway

- Bicycle and motorcycle dynamicsBicycle and motorcycle dynamicsBicycle and motorcycle dynamics is the science of the motion of bicycles and motorcycles and their components, due to the forces acting on them. Dynamics is a branch of classical mechanics, which in turn is a branch of physics. Bike motions of interest include balancing, steering, braking,...

- GyrocarGyrocarA gyrocar is a two-wheeled automobile. The difference between a bicycle or motorcycle and a gyrocar is that in a bike, dynamic balance is provided by the rider, and in some cases by the geometry and mass distribution of the bike itself...

- Segway HT