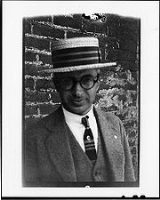

George Rappleyea

Encyclopedia

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

er, was a metallurgical engineer and the manager of the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company in Dayton, Tennessee

Dayton, Tennessee

Dayton is a city in Rhea County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 6,180 at the 2000 census. The Dayton, TN, Urban Cluster, which includes developed areas adjacent to the city and extends south to Graysville, Tennessee, had 9,050 people in 2000...

. He held this position in the summer of 1925 when he became the chief architect of the Scopes Trial

Scopes Trial

The Scopes Trial—formally known as The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes and informally known as the Scopes Monkey Trial—was a landmark American legal case in 1925 in which high school science teacher, John Scopes, was accused of violating Tennessee's Butler Act which made it unlawful to...

. During a meeting at Robinson's Drug Store it was Rappleyea who convinced a group of Dayton businessmen to sponsor a test case of the Butler Act

Butler Act

The Butler Act was a 1925 Tennessee law prohibiting public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of man’s origin. It was enacted as Tennessee Code Annotated Title 49 Section 1922...

, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in the state's schools. Rappleyea is held responsible for convincing John T. Scopes

John T. Scopes

John Thomas Scopes , was a biology teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, who was charged on May 5, 1925 for violating Tennessee's Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools...

to be the defendant in the famous "Monkey" Trial. (Note: The name is often spelled "Rappalyea" but the spelling "Rappleyea" is what appears in L. Sprague de Camp

L. Sprague de Camp

Lyon Sprague de Camp was an American author of science fiction and fantasy books, non-fiction and biography. In a writing career spanning 60 years, he wrote over 100 books, including novels and notable works of non-fiction, including biographies of other important fantasy authors...

's book The Great Monkey Trial

The Great Monkey Trial

The Great Monkey Trial is a 1968 book on the Scopes Trial by L. Sprague de Camp, first published in hardcover by Doubleday. This history of the trial was based on the memoirs of John T...

and the author interviewed Rappleyea before his death.)

George Washington Rappleyea was noted for his part in the Scopes Evolution Trial, his work as a Vice President of the Higgins Boat Company, which made landing crafts for use in WWII, his scientific patents and his part in weapons procurement for a raid on Cuba.

Early life

He was born on July 4, 1894 in New York City to George M. Rappleyea and Marian Rogers. His family was descended from the earliest Dutch settlers in what became New York State. His father was an assistant manager of various hotels between Times SquareTimes Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, at the junction of Broadway and Seventh Avenue and stretching from West 42nd to West 47th Streets...

and Herald Square

Herald Square

Herald Square is formed by the intersection of Broadway, Sixth Avenue and 34th Street in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. Named for the New York Herald, a now-defunct newspaper formerly headquartered there, it also gives its name to the surrounding area...

in New York City.

As a boy, he lived in New York City and sold newspapers at Times Square. At the age of 8, he was taking art lessons from Charles Wright, the art editor of the magazine section of the New York Sunday Herald.

His father bought a hotel in Newburgh, New York on the Hudson River

Hudson River

The Hudson is a river that flows from north to south through eastern New York. The highest official source is at Lake Tear of the Clouds, on the slopes of Mount Marcy in the Adirondack Mountains. The river itself officially begins in Henderson Lake in Newcomb, New York...

about 50 miles from New York City. At the age of 12, George took art lessons at Newburgh from Sid Turner of the Newburgh Daily News. Late in his life he claimed these art lessons helped him with some of his inventions.

In 1912 at the age of 18, he graduated from Ohio Northern College

Ohio Northern University

Ohio Northern University is a private, United Methodist Church-affiliated university located in the United States in Ada, Ohio, founded by Henry Solomon Lehr in 1871. ONU is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission and the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. ONU is a sister...

in Ada, Ohio

Ada, Ohio

Ada is a village in Hardin County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,582 at the 2000 census. In 2006, the village's population was estimated at 5,841, and the 2010 census counted 5,952 people....

with a degree in civil engineering. He was a private in the army signal corps program while at college. Various stories about him credit him with a Doctorate degree in Chemistry and Metallurgy, but we have not been able to confirm when and where he got these degrees.

Dayton, Tennessee

In 1922, he took a job as Superintendent of the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company and moved from New York to Dayton, Tennessee. The company was having financial problems. He met a nurse named Ova Corvin there after going to the hospital for a snake bite and later married her.The Tennessee Legislature passed the Butler Act

Butler Act

The Butler Act was a 1925 Tennessee law prohibiting public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of man’s origin. It was enacted as Tennessee Code Annotated Title 49 Section 1922...

forbidding the teaching of the theory of evolution in public schools. On May 4, 1925, there was an article in the Chattanooga Times that the American Civil Liberties Union

American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union is a U.S. non-profit organization whose stated mission is "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States." It works through litigation, legislation, and...

(ACLU) was interested in challenging the law. George read the article and became interested in the idea of taking up the challenge.

There were a few reasons that he might have had this interest. The first was that although he was a member of the Methodist Church

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

, he was in agreement with the evolution theory. The second possible reason may have involved a situation where he had attended a funeral for a young man who died in an accident. While there, he heard the preacher tell the parents of the deceased that he would probably go to hell because he was not baptized by the church.

The most prominent reason was that he recognized that the community could benefit economically from having what he knew would be a big trial in Dayton.

The next day Rappleyea met with a group of influential leaders that regularly had coffee at Robinson’s Drug Store in Dayton, Tennessee and proposed his idea of challenging the law. At this time, the village was having hard economic times so the group recognized the possible significance of the idea.

They decided that biology teacher John Scopes would be a good candidate to challenge the law. They sent a boy to find him on the tennis court and invited him to the discussion. He heard the proposal and felt sympathetic to the idea. He admitted to having taught evolution to his students. Of late, this was found to be a possible fabrication.

With this agreement, Rappleyea arranged to have Scopes arrested for disobeying the Butler Law. When the word got out about the case, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan was an American politician in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. He was a dominant force in the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, standing three times as its candidate for President of the United States...

, a very religious believer in the Bible and its creation teachings decided to volunteer to prosecute the case. Bryan was noted as the best orator of his day and had been a candidate for the United States presidency on three occasions.

Rappleyea went to New York City to discuss the situation with the ACLU and get their financial assistance for a defending lawyer. When Clarence Darrow

Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow was an American lawyer and leading member of the American Civil Liberties Union, best known for defending teenage thrill killers Leopold and Loeb in their trial for murdering 14-year-old Robert "Bobby" Franks and defending John T...

heard that Bryan was going to prosecute the case, he volunteered to be the defending lawyer. This set the stage for the "trial of the century".

The trial, which started on July 21, 1925, brought in news reporters and spectators from across the country. The scene attracted circus performers with monkeys and an ape. The court house temperature was very high and the court room so full that they moved the trial outdoors at one point. The debate between Byran and Darrow was long and loud. Darrow induced Bryan to take the stand as defense witness on the Bible and they had a lively debate.

In the end, Scopes lost the trial because he had admitted that he taught evolution and this was contrary to the law. The defense had wanted to appeal the decision to higher courts in order to make a challenge to the basis of the law itself, but this was rebuffed. Scopes was fined $100, but never paid it; although his conviction was upheld on appeal, the fine was thrown out for technical reasons.

Boatbuilding and WWII

By 1937, George had moved to Baltimore, Maryland where he was a representative for boatyards. In January 1937 he attended a meeting in New York City to form the American Association of Boat Builders and Repairers. On October 25, 1937, he was Director of the Wheeler Shipyard and organized a war game of 19 planes versus 10 power boats over Long Island Sound in New York where the planes dropped flour bags to hit the boats and the boats took pictures of the planes. The results of the fight were announced on November 7, 1937 and the planes won the battle.By 1939, he had moved to New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

. On December 27, 1939, he was instrumental in training boaters to get a charter to join the United States Power Squadrons

United States Power Squadrons

The United States Power Squadrons is a non-profit educational organization, founded in 1914, whose mission is to improve maritime safety and enjoyability through classes in seamanship, navigation, and other related subjects. The USPS comprises approximately 45,000 members organized into 450...

. He became a Vice President of Higgins Boat Industries

Higgins Industries

Higgins Industries was the company owned by Andrew Higgins based in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Higgins is most famous for the design and production of the Higgins boat, an amphibious landing craft referred to as LCVP, which were used extensively in D-Day Invasion of Normandy...

, a company that manufactured the famous Higgins landing crafts used in World War II. On December 31, 1939, he represented the company by complaining to the Navy about their awarding a boat contract to the British.

On May 24, 1942, he was appointed Vice President of the American Boating Association where he was head of the Legislative Committee. He authored at least 3 books while working for Higgins. In 1943, a four page book "Navigation Wrinkles for Combat Motor Boats" was published. In 1944, he published the books "Higgins System of Transportation", 18 pages, and "Caribbean Fishing", 436 pages. On September 30, 1944, "The New York Times" had an article about a patent he won on an improvement in aerial mapping cameras. In 1945, his book "Navigation Wrinkles for Combat Motor Boats" was republished with 130 pages. On April 21, 1946, he attended two boat shows in New York City as a Higgins retiree with an exhibit for marine plasticized bonded wood.

Post-WWII conspiracy

In 1946, he became Treasurer of Marsallis Construction Company in New Orleans. One of the leaders of the company was a pilot who dropped the atomic bomb on Japan. They were accumulating weapons including guns, ammunition, landing ships, tanks, planes and even a cache of atomic weapons which were stored in Gulfport, MississippiGulfport, Mississippi

Gulfport is the second largest city in Mississippi after the state capital Jackson. It is the larger of the two principal cities of the Gulfport-Biloxi, Mississippi Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is included in the Gulfport-Biloxi-Pascagoula, Mississippi Combined Statistical Area. As of the...

. This was a secret operation that was later divulged in a book by some of the pilots to be a CIA backed operation to destabilize the government of Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

. These activities were detailed in the 1964 book "The Hiroshima Pilot" by William Bradford Huie

William Bradford Huie

William Bradford "Bill" Huie was an American journalist, editor, publisher, television interviewer, screenwriter, lecturer, and novelist.-Biography:...

.

On March 2, 1947, Rappleyea was arrested in New Orleans with others for conspiracy to violate the National Firearms Act

National Firearms Act

The National Firearms Act , 73rd Congress, Sess. 2, ch. 757, , enacted on June 26, 1934, currently codified as amended as , is an Act of Congress that, in general, imposes a statutory excise tax on the manufacture and transfer of certain firearms and mandates the registration of those firearms. The...

as Secretary Treasurer of Marsallis Construction Company. On March 31, 1948, he pleaded guilty in Biloxi, Mississippi

Biloxi, Mississippi

Biloxi is a city in Harrison County, Mississippi, in the United States. The 2010 census recorded the population as 44,054. Along with Gulfport, Biloxi is a county seat of Harrison County....

Federal Court to conspiracy to ship arms and ammunition to British Honduras

British Honduras

British Honduras was a British colony that is now the independent nation of Belize.First colonised by Spaniards in the 17th century, the territory on the east coast of Central America, south of Mexico, became a British crown colony from 1862 until 1964, when it became self-governing. Belize became...

. He received a one year sentence. On April 24, 1948, he started his sentence in the Federal Correctional Institution

Federal Correctional Institution, Texarkana

The Federal Correctional Institution, Texarkana is a Federal Bureau of Prisons facility in unincorporated Bowie County, Texas, near Texarkana, Texas. The prison, near the Texas-Arkansas border, is north of Shreveport, Louisiana and east of Dallas, Texas. It is a low-security facility used for the...

at Texarkana, Texas

Texarkana, Texas

Texarkana is a city in Bowie County, Texas, United States. It effectively functions as one half of a city which crosses a state line — the other half, the city of Texarkana, Arkansas, lies on the other side of State Line Avenue...

.

Later life

In September 1951, he was living at Southport, North CarolinaSouthport, North Carolina

Southport is a city in Brunswick County, North Carolina, near the mouth of the Cape Fear River. It is part of the Wilmington Metropolitan Statistical Area...

as Director of the "Tropical Agricultural Research Laboratory, Inc." He had an invention which was featured in an article in "Popular Mechanics

Popular Mechanics

Popular Mechanics is an American magazine first published January 11, 1902 by H. H. Windsor, and has been owned since 1958 by the Hearst Corporation...

" magazine about a building material made from molasses

Molasses

Molasses is a viscous by-product of the processing of sugar cane, grapes or sugar beets into sugar. The word molasses comes from the Portuguese word melaço, which ultimately comes from mel, the Latin word for "honey". The quality of molasses depends on the maturity of the sugar cane or sugar beet,...

, plastic, and sand called "Plasmofalt". The material was hailed as breakthrough for inexpensive building materials. The material was also useful for making quick landing fields for the military on sandy islands and for driveways.

At least two structures were made with the material, one in Southport, North Carolina and another at the University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico at Albuquerque is a public research university located in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States. It is the state's flagship research institution...

. He also planned to build a factory to produce "Plasmofalt" in New Jersey. In 1955, he gave the rights to his patent to Ohio Northern College. The patent never was exploited for unknown reasons.

He had 3 patents while at Southport. He had a patent for "Dehydration of Molasses", dated March 1, 1955, also "Synthetic Bitumen Compositions", dated February 5, 1957 and "Bituminous Emulsions and the process for making them", dated April 16, 1957.

In July 1962, he lived in Miami, Florida and wrote an article in the Professional Engineering Magazine about his invention of "Plasmofalt" as a stabilizing agent in adobe construction. On June 21, 1963, he wrote a letter to Dr. Bainbridge Bunting, Associate Professor of Art & Architecture at the University of New Mexico about how he got the idea to invent "Plasmofalt". He was thanking him for building the first house ever built from "Plasmofalt" stabilized brick. At that time, he was still the Director of the Tropical Agricultural Research Laboratory, Inc. now of Miami, Florida.

In this letter, he credited his early art lessons for helping him view things in different ways. When on a trip to South America, he observed workers dumping molasses into the sea as waste. The waste molasses consumed the oxygen in the sea and killed many fish. He did not like this. He thought of his art instructors approach that there is good in all things and came up with his invention of "Plasmofalt".

He was a member of the First Humanist Society of New York

First Humanist Society of New York

In 1929 Charles Francis Potter founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included Julian Huxley, John Dewey, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann. Potter was a minister from the Unitarian tradition and in 1930 he and his wife, Clara Cook Potter, published Humanism: A New...

.

Rappleyea died in Miami on August 29, 1966 at the age of 72. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

in Washington, D.C.