Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy

Encyclopedia

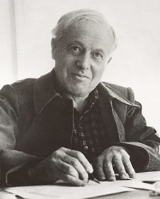

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (July 6, 1888 – February 24, 1973) was a historian

and social philosopher

, whose work spanned the disciplines of history, theology, sociology, linguistics and beyond. Born in Berlin

, Germany

into a non-observant Jewish family, the son of a prosperous banker, he converted to Christianity in his late teens, and thereafter the interpretation and reinterpretation of Christianity was a consistent theme in his writings . He met and married Margrit Hüssy in 1914. In 1925, the couple legally combined their names. They had a son, Hans, in 1921.

Rosenstock-Huessy served as an officer in the German army during World War I

. His experience caused him to reexamine the foundations of liberal Western culture. He then pursued an academic career in Germany as a specialist in medieval law, which was disrupted by the rise of Nazism

. In 1933, after Adolf Hitler

became Chancellor of Germany, he emigrated to the United States where he began a new academic career, initially at Harvard University

and then at Dartmouth College

, where he taught from 1935 to 1957.

Although never part of the mainstream of intellectual discussion during his lifetime, his work drew the attention of W. H. Auden

, Harold Berman

, Martin Marty

, Lewis Mumford

, Page Smith

, and others. Rosenstock-Huessy may be best known as the close friend of and correspondent with Franz Rosenzweig

. Their exchange of letters is considered by scholars of religion and theology to be indispensable in the study of the modern encounter of Jews with Christianity

. In his work, Rosenstock-Huessy discussed speech and language as the dominant shaper of human character and abilities in every social context. He is viewed as belonging to a group of thinkers who revived post-Nietzschean

religious thought.

, Germany

on July 6, 1888, to Theodor and Paula Rosenstock. His father, a scholarly man, was a banker and a member of the Berlin Stock Exchange

. He was the only son among seven surviving children.

Despite his parents’ Jewish heritage, his family “celebrated some Christian holidays, in keeping with other German families at the time.” He joined the Lutheran Protestant Church

Despite his parents’ Jewish heritage, his family “celebrated some Christian holidays, in keeping with other German families at the time.” He joined the Lutheran Protestant Church

at age 17 and was christened at age 18. He remained a devout proponent of Christianity throughout the rest of his life.

After graduating from a secondary school (gymnasium

) with very high academic standards and an emphasis on classical languages and literature, Rosenstock-Huessy pursued law studies at the universities of Zurich

, Heidelberg, and Berlin

. In 1909 the University of Heidelberg granted him a doctorate in law. In 1912 he became a Privatdozent

, a preliminary qualification to becoming a professor, at the University of Leipzig

, where he taught constitutional law and the history of law until 1914.

In 1914 Rosenstock-Huessy visited Florence

, Italy

to conduct historical research. There he met Margrit Hüssy, a Swiss art history major. They married later that year. World War I

broke out shortly thereafter.

, the German Army drafted Rosenstock-Huessy and stationed him at Western Front

, including 18 months at Verdun

, until the war’s end. “During this period he organized courses for the troops, replacing the limited instruction in patriotism with broader topics. In 1916, he and his friend, the Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, also on active duty, exchanged letters on Judaism and Christianity.” That correspondence has become well known as a dialog between proponents of the two related religions. Rosenstock-Huessy’s work, Judaism Despite Christianity, contains much of this correspondence.

, Germany. In 1919, he founded and became the editor until 1921 of the first factory newspaper in Germany, the Daimler Werkzeitung (Work Newspaper).

In 1921, Rosenstock founded Die Akademie der Arbeit (the Academy of Labor) in Frankfurt am Main. “This institution offered courses and seminars for blue-collar workers, but he resigned in 1923 over differences with the trade union representatives. Nevertheless, he did not give up his involvement with adult education and his efforts to give industrial workers a voice of their own in society.” He co-founded the Patmos Verlag publishing house, which published works on “new religious, philosophical, and social perspectives.”

In 1923, Rosenstock-Huessy received a second doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg. He then lectured at the Technical University of Darmstadt in the faculty of social science and social history until he was offered a job at the University of Breslau as a full professor of German legal history, a position he held from 1923 until January 30, 1933.

In 1923, Rosenstock-Huessy received a second doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg. He then lectured at the Technical University of Darmstadt in the faculty of social science and social history until he was offered a job at the University of Breslau as a full professor of German legal history, a position he held from 1923 until January 30, 1933.

During this period, Rosenstock-Huessy became active in many other ways at the University of Breslau. He helped organize voluntary work service camps—Löwenberger Arbeitslager (Löwenberg

Work Camp)—for students, young farmers, and young workers to address the living and labor conditions at coal mines in Waldenburg, Lower Silesia

.

In 1926, Joseph Wittig

, a reform-minded Roman Catholic priest, was excommunicated and thus lost his right to teach church history at the University of Breslau. Rosenstock-Huessy stood by his friend, Wittig, in this affair. In 1927-1928, they co-authored Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church), which contained two volumes of essays on the history of the Church and a third volume devoted to documents leading up to Wittig’s excommunication.

In 1925, he co-founded a journal, Die Kreatur (The Creature), which was edited by Wittig, a Roman Catholic; Martin Buber

, a Jew; and Viktor von Weizsäcker

, a Protestant, and lasted until 1930. “Among the contributors were Nicholas Berdyaev, Lev Shestov

, Franz Rosenzweig

, Ernst Simon

, Hugo Bergmann

, Hans Ehrenberg

, Rudolf Ehrenberg, Rudolf Hallo, and Florens Christian Rang. Each of these men had, between 1910 and 1932, in one way or another, offered an alternative to the idealism, positivism, and historicism that dominated German universities.”

Soon after January 30, 1933, when the National Socialists

(Nazis) assumed power in Germany, Rosenstock-Huessy resigned from the University of Breslau and departed Germany that year. By the end of 1933, he received an appointment as Lecturer in German Art and Culture at Harvard University

with the help of a professor of government there.

“While he was still teaching at Breslau, Rosenstock wrote and published the first of his major works: Die Europäischen Revolutionen: Volkscharaktere und Staatenbildung (The European Revolution

s and the Character of Nations; 1931). This book showed how 1,000 years of European history had been created from five different European national revolutions that collectively came to an end in World War I.”

Rosenstock-Huessy encountered strong opposition at Harvard University to the presentation of his ideas in social history and other topics, all of which were based on his Christian faith. Reportedly, Rosenstock-Huessy frequently mentioned God in class. He also often attacked pure, objective academic thinking, a teaching tradition assumed by the Harvard faculty to be a prerequisite for high scholarship. Profound differences of opinion ensued and led, in 1935, to his accepting an appointment as professor of social philosophy at Dartmouth College

Rosenstock-Huessy encountered strong opposition at Harvard University to the presentation of his ideas in social history and other topics, all of which were based on his Christian faith. Reportedly, Rosenstock-Huessy frequently mentioned God in class. He also often attacked pure, objective academic thinking, a teaching tradition assumed by the Harvard faculty to be a prerequisite for high scholarship. Profound differences of opinion ensued and led, in 1935, to his accepting an appointment as professor of social philosophy at Dartmouth College

in Hanover, New Hampshire

. He made his home in nearby Norwich, Vermont

. He taught at Dartmouth until his retirement in 1957.

At Harvard, he had made friends there who helped him in his publishing efforts. His first major writing task was to develop an English-language revision of his earlier book on revolutions, and he soon published Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man in 1938. George Allen Morgan, a former Harvard student under Alfred North Whitehead and himself the author of the classic What Nietzsche Means, subsequently assisted Rosenstock-Huessy in the preparation of The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun in 1946. Further, Whitehead had strongly supported Rosenstock-Huessy in his disagreements with members of the Harvard faculty.

, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and was granted approval to organize a youth training program for the Civilian Conservation Corps

(CCC). Eleanor Roosevelt

and journalist Dorothy Thompson

were champions of the proposal. He then founded Camp William James

in Tunbridge

, Vermont

as a prototype for a national peacetime volunteer labor service. “Involving mainly students from Dartmouth, Radcliffe, and Harvard, its purpose was to train young leaders to expand the 7-year-old CCC from a program for unemployed youth into a work service program that would accept volunteers from all walks of life.”, The entrance of the United States into World War II

in 1941 ended this and all other CCC programs because men were needed in the armed services and women became a greater part of the workforce. This concept anticipated the Peace Corps

by more than two decades.

Rosenstock-Huessy published Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man in 1938, an English-language revision of his earlier book on revolutions. Together with George Allen Morgan, he published The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun in 1946. In Out of Revolution

Rosenstock-Huessy published Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man in 1938, an English-language revision of his earlier book on revolutions. Together with George Allen Morgan, he published The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun in 1946. In Out of Revolution

, Rosenstock-Huessy wrote:

During 1956 through 1958, Rosenstock-Huessy developed the principle of metanomics in his two-volume Soziologie

(Sociology)—Volume I: On the Forces of Common Life (When Space Governs) and Volume II: On the Forces of History (When the Times Are Obeyed). During 1963 through 1964, he further developed this principle in Volumes I & II of, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts: Eine Leibhaftige Grammatik in Vier Teilen (The Speech of Mankind: A Personal Grammar in Four Parts). Whereas Soziologie is unavailable in English, Rosenstock-Huessy's Speech and Reality

is an English-language introduction to that work. A collection of his writings, I Am an Impure Thinker

offers a good overview of Rosenstock-Huessy's thought processes.

became Rosenstock-Huessy's companion. She is the widow of Helmuth James von Moltke

, who had opposed National Socialism and was executed by the Nazis.

After World War II and continuing through his retirement from Dartmouth, Rosenstock-Huessy was a frequent guest professor at many universities in Germany and the United States. He remained active in lecturing and writing until his final years. His output comprises more than 500 essays, articles, and monographs, as well as 40 books. He was awarded an honorary doctoral degree in 1958 at the University of Münster

. Rosenstock-Huessy died on February 24, 1973.

He is said to have invented the phrases, "the world is a global village", "think global, act local", during the 1960's or earlier. He is said to have had an influence on the founding of summer camps for school-children in the USA, the US Peace Corps, and the School of Human Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

and social philosopher

Social philosophy

Social philosophy is the philosophical study of questions about social behavior . Social philosophy addresses a wide range of subjects, from individual meanings to legitimacy of laws, from the social contract to criteria for revolution, from the functions of everyday actions to the effects of...

, whose work spanned the disciplines of history, theology, sociology, linguistics and beyond. Born in Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

into a non-observant Jewish family, the son of a prosperous banker, he converted to Christianity in his late teens, and thereafter the interpretation and reinterpretation of Christianity was a consistent theme in his writings . He met and married Margrit Hüssy in 1914. In 1925, the couple legally combined their names. They had a son, Hans, in 1921.

Rosenstock-Huessy served as an officer in the German army during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. His experience caused him to reexamine the foundations of liberal Western culture. He then pursued an academic career in Germany as a specialist in medieval law, which was disrupted by the rise of Nazism

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

. In 1933, after Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

became Chancellor of Germany, he emigrated to the United States where he began a new academic career, initially at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

and then at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College is a private, Ivy League university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. The institution comprises a liberal arts college, Dartmouth Medical School, Thayer School of Engineering, and the Tuck School of Business, as well as 19 graduate programs in the arts and sciences...

, where he taught from 1935 to 1957.

Although never part of the mainstream of intellectual discussion during his lifetime, his work drew the attention of W. H. Auden

W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden , who published as W. H. Auden, was an Anglo-American poet,The first definition of "Anglo-American" in the OED is: "Of, belonging to, or involving both England and America." See also the definition "English in origin or birth, American by settlement or citizenship" in See also...

, Harold Berman

Harold J. Berman

Harold J. Berman was an American legal scholar who was an expert in comparative, international and Soviet/Russian law as well as legal history, philosophy of law and the intersection of law and religion...

, Martin Marty

Martin E. Marty

Martin Emil Marty is an American Lutheran religious scholar who has written extensively on 19th century and 20th century American religion. He received a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1956, and served as a Lutheran pastor from 1952 to 1962 in the suburbs of Chicago...

, Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford was an American historian, philosopher of technology, and influential literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a writer...

, Page Smith

Page Smith

Charles Page Smith , who was known by his middle name, was a U.S. historian, professor, author, and newspaper columnist....

, and others. Rosenstock-Huessy may be best known as the close friend of and correspondent with Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig was an influential Jewish theologian and philosopher.-Early life:Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany to a middle-class, minimally observant Jewish family...

. Their exchange of letters is considered by scholars of religion and theology to be indispensable in the study of the modern encounter of Jews with Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

. In his work, Rosenstock-Huessy discussed speech and language as the dominant shaper of human character and abilities in every social context. He is viewed as belonging to a group of thinkers who revived post-Nietzschean

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

religious thought.

Early life

Rosenstock-Huessy was born Eugen Friedrich Moritz Rosenstock in BerlinBerlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

on July 6, 1888, to Theodor and Paula Rosenstock. His father, a scholarly man, was a banker and a member of the Berlin Stock Exchange

Berliner Börse

Börse Berlin AG is a stock exchange based in Berlin, Germany, founded in 1685 through an edict of Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm and is one of the oldest exchanges in Germany...

. He was the only son among seven surviving children.

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

at age 17 and was christened at age 18. He remained a devout proponent of Christianity throughout the rest of his life.

After graduating from a secondary school (gymnasium

Gymnasium (school)

A gymnasium is a type of school providing secondary education in some parts of Europe, comparable to English grammar schools or sixth form colleges and U.S. college preparatory high schools. The word γυμνάσιον was used in Ancient Greece, meaning a locality for both physical and intellectual...

) with very high academic standards and an emphasis on classical languages and literature, Rosenstock-Huessy pursued law studies at the universities of Zurich

University of Zurich

The University of Zurich , located in the city of Zurich, is the largest university in Switzerland, with over 25,000 students. It was founded in 1833 from the existing colleges of theology, law, medicine and a new faculty of philosophy....

, Heidelberg, and Berlin

Humboldt University of Berlin

The Humboldt University of Berlin is Berlin's oldest university, founded in 1810 as the University of Berlin by the liberal Prussian educational reformer and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt, whose university model has strongly influenced other European and Western universities...

. In 1909 the University of Heidelberg granted him a doctorate in law. In 1912 he became a Privatdozent

Privatdozent

Privatdozent or Private lecturer is a title conferred in some European university systems, especially in German-speaking countries, for someone who pursues an academic career and holds all formal qualifications to become a tenured university professor...

, a preliminary qualification to becoming a professor, at the University of Leipzig

University of Leipzig

The University of Leipzig , located in Leipzig in the Free State of Saxony, Germany, is one of the oldest universities in the world and the second-oldest university in Germany...

, where he taught constitutional law and the history of law until 1914.

In 1914 Rosenstock-Huessy visited Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

to conduct historical research. There he met Margrit Hüssy, a Swiss art history major. They married later that year. World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

broke out shortly thereafter.

World War I

At the onset of World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, the German Army drafted Rosenstock-Huessy and stationed him at Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

, including 18 months at Verdun

Battle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun was one of the major battles during the First World War on the Western Front. It was fought between the German and French armies, from 21 February – 18 December 1916, on hilly terrain north of the city of Verdun-sur-Meuse in north-eastern France...

, until the war’s end. “During this period he organized courses for the troops, replacing the limited instruction in patriotism with broader topics. In 1916, he and his friend, the Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, also on active duty, exchanged letters on Judaism and Christianity.” That correspondence has become well known as a dialog between proponents of the two related religions. Rosenstock-Huessy’s work, Judaism Despite Christianity, contains much of this correspondence.

Interwar period

After World War I, Rosenstock-Huessy became active in labor issues, focusing on improving education as a means to improve the societal standard of living. He returned to academia and started publishing his first noted works.Labor education

Rosenstock-Huessy did not return to his teaching post at the University of Leipzig. Instead, he obtained a position with Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft, the German car manufacturer, in StuttgartStuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

, Germany. In 1919, he founded and became the editor until 1921 of the first factory newspaper in Germany, the Daimler Werkzeitung (Work Newspaper).

In 1921, Rosenstock founded Die Akademie der Arbeit (the Academy of Labor) in Frankfurt am Main. “This institution offered courses and seminars for blue-collar workers, but he resigned in 1923 over differences with the trade union representatives. Nevertheless, he did not give up his involvement with adult education and his efforts to give industrial workers a voice of their own in society.” He co-founded the Patmos Verlag publishing house, which published works on “new religious, philosophical, and social perspectives.”

Return to academia

During this period, Rosenstock-Huessy became active in many other ways at the University of Breslau. He helped organize voluntary work service camps—Löwenberger Arbeitslager (Löwenberg

Lwówek Slaski

Lwówek Śląski is a town in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship in Poland. Situated on the Bóbr River, Lwówek Śląski is about 30 km NNW of Jelenia Góra and has a population of about 10,300 inhabitants...

Work Camp)—for students, young farmers, and young workers to address the living and labor conditions at coal mines in Waldenburg, Lower Silesia

Province of Lower Silesia

The Province of Lower Silesia was a province of the Free State of Prussia from 1919 to 1945. Between 1938 and 1941 it was reunited with Upper Silesia as the Silesia Province. The capital of Lower Silesia was Breslau...

.

In 1926, Joseph Wittig

Joseph Wittig

Joseph Wittig was a German theologian and writer who was born in Neusorge, a village in the district of Neurode, Silesia....

, a reform-minded Roman Catholic priest, was excommunicated and thus lost his right to teach church history at the University of Breslau. Rosenstock-Huessy stood by his friend, Wittig, in this affair. In 1927-1928, they co-authored Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church), which contained two volumes of essays on the history of the Church and a third volume devoted to documents leading up to Wittig’s excommunication.

In 1925, he co-founded a journal, Die Kreatur (The Creature), which was edited by Wittig, a Roman Catholic; Martin Buber

Martin Buber

Martin Buber was an Austrian-born Jewish philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of religious existentialism centered on the distinction between the I-Thou relationship and the I-It relationship....

, a Jew; and Viktor von Weizsäcker

Viktor von Weizsäcker

Viktor Freiherr von Weizsäcker was a German physician and physiologist. He was the brother of Ernst von Weizsäcker, and uncle to Richard von Weizsäcker and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. .He studied at Tübingen, Freiburg, Berlin, and Heidelberg, where he earned his medical degree in 1910...

, a Protestant, and lasted until 1930. “Among the contributors were Nicholas Berdyaev, Lev Shestov

Lev Shestov

Lev Isaakovich Shestov , born Yehuda Leyb Schwarzmann , was a Ukrainian/Russian existentialist philosopher. Born in Kiev on , he emigrated to France in 1921, fleeing from the aftermath of the October Revolution. He lived in Paris until his death on November 19, 1938.- Life :Shestov was born Lev...

, Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig was an influential Jewish theologian and philosopher.-Early life:Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany to a middle-class, minimally observant Jewish family...

, Ernst Simon

Ernst Simon

Ernst Akiba/Akiva Simon, or aqibhah Ernst Simon , was a German-Israeli Jewish educator, and religious philosopher. Along with Martin Buber, he founded in the 1920s one of the earliest Israeli peace groups, Brit Shalom, which advocated for a binational state including Jews and Arabs...

, Hugo Bergmann

Hugo Bergmann

Samuel Hugo Bergman, or Samuel Bergman was a German and Israeli Jewish philosopher.-Biography:...

, Hans Ehrenberg

Hans Ehrenberg

Hans Philipp Ehrenberg was a German theologian. One of the co-founders of the Confessing Church, he was forced to emigrate to England because of his Jewish ancestry and his opposition to National Socialism....

, Rudolf Ehrenberg, Rudolf Hallo, and Florens Christian Rang. Each of these men had, between 1910 and 1932, in one way or another, offered an alternative to the idealism, positivism, and historicism that dominated German universities.”

Soon after January 30, 1933, when the National Socialists

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

(Nazis) assumed power in Germany, Rosenstock-Huessy resigned from the University of Breslau and departed Germany that year. By the end of 1933, he received an appointment as Lecturer in German Art and Culture at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

with the help of a professor of government there.

Publications 1914–1933

Rosenstock-Huessy published his medieval study Königshaus und Stämme in Deutschland zwischen 911 und 1250 (The Royal House and the Tribes in Germany between 911 and 1250) in 1914, which he had written in Leipzig and was the source of recognition for his second doctorate. In 1920, Rosenstock-Huessy published Die Hochzeit des Krieges und der Revolution (The Marriage of War and Revolution), “a collection of current events essays that were replete with visionary thinking and practical warnings of conflicts to come.” In 1921, Rosenstock-Huessy published Angewandte Seelenkunde (Practical Knowledge of the Soul) wherein he developed a new method for the social sciences based on language, the spoken word, and his "grammatical approach." He later called this approach "metanomics." Together with Josef Wittig, a Roman Catholic, he published Das Alter der Kirche (The Age of the Church) in 1927-28. That work contained two volumes of essays on the life of the Church and a third volume devoted to documents leading up to Wittig’s excommunication.”“While he was still teaching at Breslau, Rosenstock wrote and published the first of his major works: Die Europäischen Revolutionen: Volkscharaktere und Staatenbildung (The European Revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

s and the Character of Nations; 1931). This book showed how 1,000 years of European history had been created from five different European national revolutions that collectively came to an end in World War I.”

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College is a private, Ivy League university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. The institution comprises a liberal arts college, Dartmouth Medical School, Thayer School of Engineering, and the Tuck School of Business, as well as 19 graduate programs in the arts and sciences...

in Hanover, New Hampshire

Hanover, New Hampshire

Hanover is a town along the Connecticut River in Grafton County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 11,260 at the 2010 census. CNN and Money magazine rated Hanover the sixth best place to live in America in 2011, and the second best in 2007....

. He made his home in nearby Norwich, Vermont

Norwich, Vermont

Norwich is a town in Windsor County, Vermont, United States, located along the Connecticut River opposite Hanover, New Hampshire. The population was 3,544 at the 2000 census....

. He taught at Dartmouth until his retirement in 1957.

At Harvard, he had made friends there who helped him in his publishing efforts. His first major writing task was to develop an English-language revision of his earlier book on revolutions, and he soon published Out of Revolution: Autobiography of Western Man in 1938. George Allen Morgan, a former Harvard student under Alfred North Whitehead and himself the author of the classic What Nietzsche Means, subsequently assisted Rosenstock-Huessy in the preparation of The Christian Future or the Modern Mind Outrun in 1946. Further, Whitehead had strongly supported Rosenstock-Huessy in his disagreements with members of the Harvard faculty.

Renewed labor education

In 1940 he presented a request to US PresidentPresident of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and was granted approval to organize a youth training program for the Civilian Conservation Corps

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a public work relief program that operated from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men from relief families, ages 18–25. A part of the New Deal of President Franklin D...

(CCC). Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was the First Lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945. She supported the New Deal policies of her husband, distant cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and became an advocate for civil rights. After her husband's death in 1945, Roosevelt continued to be an international...

and journalist Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Thompson was an American journalist and radio broadcaster, who in 1939 was recognized by Time magazine as the second most influential women in America next to Eleanor Roosevelt...

were champions of the proposal. He then founded Camp William James

Camp William James

Camp William James was opened in 1940 by Dartmouth College professor, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, as a center for training youth for leadership in the Civilian Conservation Corps, which had been inaugurated in 1933 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt...

in Tunbridge

Tunbridge

Tunbridge may refer to:* Tunbridge, Tasmania, Australia* The old spelling of Tonbridge, UK* Royal Tunbridge Wells, UK* Tunbridge, Vermont, USA...

, Vermont

Vermont

Vermont is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. The state ranks 43rd in land area, , and 45th in total area. Its population according to the 2010 census, 630,337, is the second smallest in the country, larger only than Wyoming. It is the only New England...

as a prototype for a national peacetime volunteer labor service. “Involving mainly students from Dartmouth, Radcliffe, and Harvard, its purpose was to train young leaders to expand the 7-year-old CCC from a program for unemployed youth into a work service program that would accept volunteers from all walks of life.”, The entrance of the United States into World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

in 1941 ended this and all other CCC programs because men were needed in the armed services and women became a greater part of the workforce. This concept anticipated the Peace Corps

Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an American volunteer program run by the United States Government, as well as a government agency of the same name. The mission of the Peace Corps includes three goals: providing technical assistance, helping people outside the United States to understand US culture, and helping...

by more than two decades.

Publications 1933–1973

Out of Revolution

Out of Revolution is a book by Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy , German social philosopher. The book counters conventional historiography as a “theory of history: how history should be understood, how historians should write about it,” as Harold J...

, Rosenstock-Huessy wrote:

The present time is bound (...) to attempt an organization of future society by which the dynamite of revolution may be manipulated as persistently and consciously as contractors use real dynamite in building tunnels or roads.

During 1956 through 1958, Rosenstock-Huessy developed the principle of metanomics in his two-volume Soziologie

Soziologie

Soziologie is a book by Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy , German social philosopher, addressing the spatial and temporal influences on “human life, language and associations. To Rosenstock-Huessy, speech is central to sociology; sociology must recognize that speech is the concrete form of social...

(Sociology)—Volume I: On the Forces of Common Life (When Space Governs) and Volume II: On the Forces of History (When the Times Are Obeyed). During 1963 through 1964, he further developed this principle in Volumes I & II of, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts: Eine Leibhaftige Grammatik in Vier Teilen (The Speech of Mankind: A Personal Grammar in Four Parts). Whereas Soziologie is unavailable in English, Rosenstock-Huessy's Speech and Reality

Speech and Reality

Speech and Reality is a book by Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy , German social philosopher and is an English-language introduction to Rosenstock-Huessy’s German-language book, Soziologie. It comprises seven essays that he wrote and revised between 1935 and 1955...

is an English-language introduction to that work. A collection of his writings, I Am an Impure Thinker

I Am an Impure Thinker

I Am an Impure Thinker is a book by Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy , German social philosopher and is an English-language introduction to Rosenstock-Huessy’s German-language book, Soziologie. It is a collection of essays, which represents an accessible introduction to Rosenstock-Huessy’s thought...

offers a good overview of Rosenstock-Huessy's thought processes.

Transitions

Rosenstock-Huessy's wife, Margrit, died in 1959. In 1960, Freya von MoltkeFreya von Moltke

Freya von Moltke was a participant in the anti-Nazi resistance group, the Kreisau Circle, with her husband, Helmuth James Graf von Moltke...

became Rosenstock-Huessy's companion. She is the widow of Helmuth James von Moltke

Helmuth James Graf von Moltke

Helmuth James Graf von Moltke was a German jurist who, as a draftee in the German Abwehr, acted to subvert German human-rights abuses of people in territories occupied by Germany during World War II and subsequently became a founding member of the Kreisau Circle resistance group, whose members...

, who had opposed National Socialism and was executed by the Nazis.

After World War II and continuing through his retirement from Dartmouth, Rosenstock-Huessy was a frequent guest professor at many universities in Germany and the United States. He remained active in lecturing and writing until his final years. His output comprises more than 500 essays, articles, and monographs, as well as 40 books. He was awarded an honorary doctoral degree in 1958 at the University of Münster

University of Münster

The University of Münster is a public university located in the city of Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany. The WWU is part of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, a society of Germany's leading research universities...

. Rosenstock-Huessy died on February 24, 1973.

He is said to have invented the phrases, "the world is a global village", "think global, act local", during the 1960's or earlier. He is said to have had an influence on the founding of summer camps for school-children in the USA, the US Peace Corps, and the School of Human Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

External links

- The Papers of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy in Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College

- The official web site of the Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Fund and Argo Books includes a biography, accessed 20 March 2007

- The Norwich Center, Norwich, Vermont, maintains an internet site devoted to an introductory biography and appreciation of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, signed by Clinton C. Gardner, President of the Norwich Center, accessed 20 March 2007

- Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy Gesellschaft