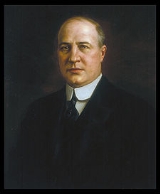

Edwin P. Morrow

Encyclopedia

Edwin Porch Morrow was an American

politician who served as the 40th Governor of Kentucky

from 1919 to 1923. He was the only Republican

elected to this office between 1907 and 1927. He championed the typical Republican causes of his day, namely equal rights for African-Americans and the use of force to quell violence. Morrow had been schooled in his party's principles by his father, Thomas Z. Morrow

, who was its candidate for governor in 1883, and his uncle, William O. Bradley, who was elected governor in 1895. Both men were founding members of the Republican Party in Kentucky.

After rendering non-combat service in the Spanish–American War, Morrow graduated from the University of Cincinnati Law School in 1902 and opened his practice in Lexington

, Kentucky. He made a name for himself almost immediately by securing the acquittal of a black man who had been charged with murder based on an extorted confession and perjured testimony. He was appointed U.S. District Attorney

for the Eastern District of Kentucky

by President William Howard Taft

in 1910 and served until he was removed from office in 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson

. In 1915, he ran for governor against his good friend, Augustus O. Stanley

. Stanley won the election by 471 votes, making the 1915 contest the closest gubernatorial race in the state's history.

Morrow ran for governor again in 1919. His opponent, James D. Black

, had ascended to the governorship earlier that year when Stanley resigned to take a seat in the U.S. Senate

. Morrow encouraged voters to "Right the Wrong of 1915" and ran on a progressive

platform that included women's suffrage

and quelling racial violence

. He charged the Democratic administration with corruption, citing specific examples, and won the general election in a landslide. With a friendly legislature in 1920, he passed much of his agenda into law including an anti-lynching

law and a reorganization of state government. He won national acclaim for preventing the lynching of a black prisoner in 1920. He was not hesitant to remove local officials who did not prevent or quell mob violence. By 1922, Democrats regained control of the General Assembly

, and Morrow was not able to accomplish much in the second half of his term. Following his term as governor, he served on the United States Railroad Labor Board and the Railway Mediation Board, but never again held elected office. He died of a heart attack on June 15, 1935, while living with a cousin in Frankfort

.

, Kentucky, on November 28, 1877. He and his twin brother, Charles, were the youngest of eight children. His father was one of the founders of the Republican Party in Kentucky and an unsuccessful candidate for governor in 1883. His mother was a sister to William O'Connell Bradley

, who was elected the first Republican governor of Kentucky in 1895.

Morrow's early education was in the public schools of Somerset. At age 14, he entered preparatory school at St. Mary's College

near Lebanon

, Kentucky. He continued there throughout 1891 and 1892. From there, he enrolled at Cumberland College (now the University of the Cumberlands

) in Williamsburg, Kentucky

, and distinguished himself in the debating society. He was also interested in sports, playing halfback

on the football

team and left field

on the baseball team.

On June 24, 1898, Morrow enlisted as a private

in the 4th Kentucky Infantry Regiment for service in the Spanish–American War. He was first stationed at Lexington, Kentucky

, and later trained at Anniston, Alabama

. Due to a bout with typhoid fever

, he never saw active duty, and mustered out as a second lieutenant

on February 12, 1899. In 1900, he matriculated for the fall semester at the University of Cincinnati Law School. He graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

degree in 1902.

Morrow opened his practice in Lexington. He established his reputation in one of his first cases—the trial of William Moseby, a black man accused of murder. Moseby's first trial had ended in a hung jury

, but because the evidence against him included a confession (which he later recanted), most observers believed he would be convicted in his second trial. Unable to find a defense lawyer for Moseby, the judge in the case turned to Morrow, who as a young lawyer was eager for work. Morrow proved that his client's testimony had been extorted; he had been told that a lynch mob waited outside the jail for him, but no such mob had ever existed. Morrow further showed that other testimony against his client was false. Moseby was acquitted September 21, 1902.

Morrow returned to Somerset in 1903. There, he married Katherine Hale Waddle on June 18, 1903. Waddle's father had studied law under Morrow's father, and Edwin and Katherine had been playmates, schoolmates, and later sweethearts. The couple had two children, Edwina Haskell in July 1904 and Charles Robert in November 1908.

for Somerset, serving until 1908. President William Howard Taft

appointed him U.S. District Attorney

for the Eastern District of Kentucky

in 1910. He continued in this position until he was removed from office by President Woodrow Wilson

in 1913.

Morrow's first political experience was working in his uncle William O. Bradley's gubernatorial campaign in 1895. In 1899, Republican gubernatorial candidate William S. Taylor

Morrow's first political experience was working in his uncle William O. Bradley's gubernatorial campaign in 1895. In 1899, Republican gubernatorial candidate William S. Taylor

offered to make Morrow his Secretary of State in exchange for Bradley's support in the election; Bradley refused. Despite the encouragement of friends, Morrow declined to run for governor in 1911.

In 1912, Morrow was chosen as the Republican candidate for the Senate seat of Thomas Paynter. Paynter had decided not to seek re-election, and the Democrats nominated Ollie M. James

of Crittenden County

. The General Assembly

was heavily Democratic and united behind James. On a joint ballot, James defeated Morrow by a vote of 105–28. Due to the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment

the next year, this was the last time the Kentucky legislature would elect a senator.

At the state Republican convention in Lexington on June 15, 1915, Morrow was chosen as the Republican candidate for governor over Latt F. McLaughlin. His Democratic

opponent was his close friend, Augustus O. Stanley

. Morrow charged previous Democratic administrations with corruption and called for the election of a Republican because "You cannot clean house with a dirty broom." Both men ran on progressive platforms, and the election went in Stanley's favor by only 471 votes. Although it was the closest gubernatorial vote in the state's history, Morrow refused to challenge the results, which greatly increased his popularity. His decision was influenced by the fact that a challenge would be decided by the General Assembly

, which had a Democratic majority in both houses.

in 1916

, 1920

, and 1928

. In 1919, he was chosen by acclamation as his party's candidate for governor. This time, his opponent was James D. Black

. Black was Stanley's lieutenant governor

and had ascended to the governorship in May 1919 when Stanley resigned to take a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Morrow encouraged the state's voters to "Right the Wrong of 1915". He again ran on a progressive platform, advocating an amendment to the state constitution

to grant women's suffrage. His support was not as strong for a prohibition

amendment. He attacked the Stanley–Black administration as corrupt. Days before the election, he exposed a contract awarded by the state Board of Control to a non-existent company. Historian Lowell H. Harrison

opined that Black's refusal to remove the members of the board following this revelation probably sealed his defeat. Morrow won the general election by more than 40,000 votes. It was the largest margin of victory for a Republican gubernatorial candidate in the state's history.

On January 6, 1920, Governor Morrow signed the bill ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment

, making Kentucky the 23rd state to ratify it, and the moment is captured in a photograph with members of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association

. During the 1920 legislative session, the Republicans held a majority in the state House of Representatives

and were a minority by only two votes in the state Senate

. During the session, Morrow was often able to convince C. W. Burton, a Democratic senator from Grant County

, to support Republican proposals. Tie votes in the Senate were broken by Republican lieutenant governor S. Thruston Ballard

. Consequently, Morrow was able to effect a considerable reorganization of the state government, including replacing the Board of Control with a nonpartisan Board of Charities and Corrections, centralizing highway works, and revising property taxes. He oversaw improvements to the education system, including better textbook selection and a tax on racetracks to support a minimum salary for teachers. Among Morrow's reforms that did not pass was a proposal to make the judiciary

nonpartisan.

Morrow urged enforcement of state laws against carrying concealed weapons and restricted activities of the Ku Klux Klan

. During his first year in office, he granted only 100 pardons. This was a considerable decrease from the number granted by his immediate predecessors. During their first years in office, J. C. W. Beckham

granted 350 pardons, James B. McCreary

(during his second stint as governor) granted 139, and Augustus O. Stanley granted 257. He was also an active member of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation

, a society for the elimination of racial violence in the South.

On February 9, 1920, Morrow dispatched the Kentucky National Guard

On February 9, 1920, Morrow dispatched the Kentucky National Guard

to Lexington to protect Will Lockett, a black World War I veteran on trial for murder. Morrow told the state adjutant general

"Do as much as you have to do to keep that negro in the hands of the law. If he falls into the hands of the mob I do not expect to see you alive." Lockett had already confessed, without the benefit of a lawyer, to the murder. His trial took only thirty minutes as he pleaded guilty but asked for a life sentence instead of death. Despite his plea, he was sentenced to die in the electric chair.

A crowd of several thousand gathered outside the courthouse while Lockett's trial was underway. A cameraman asked a large group of those gathered to shake their fists and yell so he could get a picture. The rest of the crowd mistakenly believed they were storming the courthouse and rushed forward. In the ensuing skirmish, one policeman was injured so badly that his arm later had to be amputated. The National Guard opened fire, killing six people and wounding approximately fifty. Some members of the mob looted nearby stores in search of weapons to retaliate, but reinforcements arrived from a nearby army post by mid-afternoon. Martial law

was declared, and no further violence was perpetrated. A month later, Lockett was executed at the Kentucky State Penitentiary

in Eddyville

.

The incident is believed to be the first forceful suppression of a lynch mob by state and local officials in the South

. Morrow received a laudatory telegram from the NAACP

, and most of the national press regarding the incident was favorable. W. E. B. Du Bois called it the "Second Battle of Lexington

". Morrow was consistent in his use of state troops to end violence in the state. In 1922, he again dispatched the National Guard to quell a violent mill strike in Newport

.

Morrow also demanded consistency from local law enforcement officials. In 1921, he removed the Woodford County

jailer from office because he allowed a black inmate to be lynched and offered a reward of $25,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators. Citizens of Versailles

were more outraged that the jailer had been removed from office than that the prisoner had been lynched. The locals refused to aid in the investigation, and the lynchers were never arrested or charged. Local officials appointed the jailer's wife to finish his term in an attempt to skirt the removal.

In August 1922, a traveling salesman named Jack Eaton was arrested for allegedly assault

ing several young girls. The girls' parents refused to press charges, and Eaton was released. Later, he was captured by a mob, who cut him several times and poured turpentine into his wounds. An investigation found that the Scott County

sheriff

had willfully delivered Eaton to the mob, and Morrow removed him from office. Though Eaton was a white man, blacks were elated with the removal because they hoped it would encourage other jailers to step up efforts to protect against lynchings and mob violence.

Morrow was frequently mentioned as a potential candidate for vice president

in 1920, but he withdrew his name from consideration, sticking to a campaign promise not to seek a higher office while governor. On July 27, 1920, he made a speech in Northampton

, Massachusetts, officially notifying Calvin Coolidge

of his nomination for that office. Although he supported Frank O. Lowden for president, the nomination went to Warren G. Harding

, and Morrow campaigned vigorously on behalf of his party's ticket.

In his address to the 1922 legislature, Morrow asked for for improvements to the state highway system and for the repeal of all laws denying equal rights to women. He also recommended a large bond

issue to finance improvements to the state's universities, schools, prisons, and hospitals. By this time, however, the Republicans had surrendered their majority in the state House, and practically all of Morrow's proposals were voted down. Morrow countered by vetoing several Democratic bills, including $700,000 in appropriations. Among the few accomplishments of the 1922 legislature were passage of an anti-lynching law, the abolition of convict labor

and the establishment of normal schools at Murray

and Morehead

. Today, these schools are Murray State University

and Morehead State University

, respectively. The 1922 legislature also established a commission to govern My Old Kentucky Home State Park

and approved construction of the Jefferson Davis Monument

.

Despite the fact that Morrow gained national praise for his handling of the Lockett trial, historian James Klotter opined that he "left behind a solid, and rather typical, record for a Kentucky governor." He cited Morrow's fiscal conservatism and inability to control the legislature in 1922 as reasons for his lackluster assessment, although he praised Morrow's advancement of racial equality in the state. Morrow was prohibited by the state constitution from seeking a second consecutive term, and the achievements of his administration were not significant enough to ensure the election of Charles I. Dawson

, his would-be Republican successor in the gubernatorial election of 1923.

representing the Ninth District

, but lost his party's nomination to John M. Robsion

.

Following his defeat in the congressional primary, Morrow made plans to return to Lexington to resume his law practice. On June 15, 1935, he died unexpectedly of a heart attack while temporarily living with a cousin in Frankfort

. He is buried in Frankfort Cemetery

.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

politician who served as the 40th Governor of Kentucky

Governor of Kentucky

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of the executive branch of government in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Fifty-six men and one woman have served as Governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-election once...

from 1919 to 1923. He was the only Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

elected to this office between 1907 and 1927. He championed the typical Republican causes of his day, namely equal rights for African-Americans and the use of force to quell violence. Morrow had been schooled in his party's principles by his father, Thomas Z. Morrow

Thomas Z. Morrow

Thomas Zanzinger Morrow was a lawyer, judge, and politician from Kentucky. He was one of twenty-eight men who founded the Kentucky Republican Party. His brother-in-law, William O. Bradley, was elected governor of Kentucky in 1895, and his son, Edwin P...

, who was its candidate for governor in 1883, and his uncle, William O. Bradley, who was elected governor in 1895. Both men were founding members of the Republican Party in Kentucky.

After rendering non-combat service in the Spanish–American War, Morrow graduated from the University of Cincinnati Law School in 1902 and opened his practice in Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

, Kentucky. He made a name for himself almost immediately by securing the acquittal of a black man who had been charged with murder based on an extorted confession and perjured testimony. He was appointed U.S. District Attorney

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

for the Eastern District of Kentucky

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky is the Federal district court whose jurisdiction comprises approximately the Eastern half of the state of Kentucky....

by President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

in 1910 and served until he was removed from office in 1913 by President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

. In 1915, he ran for governor against his good friend, Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus Owsley Stanley I was a politician from the US state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 38th Governor of Kentucky and also represented the state in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate...

. Stanley won the election by 471 votes, making the 1915 contest the closest gubernatorial race in the state's history.

Morrow ran for governor again in 1919. His opponent, James D. Black

James D. Black

James Dixon Black was the 39th Governor of Kentucky, serving for seven months in 1919. He ascended to the office when Governor Augustus O. Stanley was elected to the U.S. Senate....

, had ascended to the governorship earlier that year when Stanley resigned to take a seat in the U.S. Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. Morrow encouraged voters to "Right the Wrong of 1915" and ran on a progressive

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States is a broadly based reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century and is generally considered to be middle class and reformist in nature. It arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large...

platform that included women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

and quelling racial violence

Mass racial violence in the United States

Mass racial violence, also called race riots can include such disparate events as:* attacks on Irish Catholics, the Chinese and other immigrants in the 19th century....

. He charged the Democratic administration with corruption, citing specific examples, and won the general election in a landslide. With a friendly legislature in 1920, he passed much of his agenda into law including an anti-lynching

Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial execution carried out by a mob, often by hanging, but also by burning at the stake or shooting, in order to punish an alleged transgressor, or to intimidate, control, or otherwise manipulate a population of people. It is related to other means of social control that...

law and a reorganization of state government. He won national acclaim for preventing the lynching of a black prisoner in 1920. He was not hesitant to remove local officials who did not prevent or quell mob violence. By 1922, Democrats regained control of the General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

, and Morrow was not able to accomplish much in the second half of his term. Following his term as governor, he served on the United States Railroad Labor Board and the Railway Mediation Board, but never again held elected office. He died of a heart attack on June 15, 1935, while living with a cousin in Frankfort

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

.

Early life

Edwin Morrow was born to Thomas Zanzinger and Virginia Catherine (Bradley) Morrow in SomersetSomerset, Kentucky

The major demographic differences between the city and the micropolitan area relate to income, housing composition and age. The micropolitan area, as compared to the incorporated city, is more suburban in flavor and has a significantly younger housing stock, a higher income, and contains most of...

, Kentucky, on November 28, 1877. He and his twin brother, Charles, were the youngest of eight children. His father was one of the founders of the Republican Party in Kentucky and an unsuccessful candidate for governor in 1883. His mother was a sister to William O'Connell Bradley

William O'Connell Bradley

William O'Connell Bradley was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He served as the 32nd Governor of Kentucky and was later elected by the state legislature as a U.S. senator from that state...

, who was elected the first Republican governor of Kentucky in 1895.

Morrow's early education was in the public schools of Somerset. At age 14, he entered preparatory school at St. Mary's College

St. Mary's College (Kentucky)

St. Mary's College was an institution established in 1821 by William Byrne.St. Mary's was still a functioning college in 1899.St. Mary's College closed in 1976.-Notable alumni:*Clement S. Hill, U.S. Congressman from Kentucky...

near Lebanon

Lebanon, Kentucky

Lebanon is a city in Marion County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 6,331 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Marion County. Lebanon is located in central Kentucky, southeast of Louisville. A national cemetery is located nearby....

, Kentucky. He continued there throughout 1891 and 1892. From there, he enrolled at Cumberland College (now the University of the Cumberlands

University of the Cumberlands

University of the Cumberlands is a private, liberal arts college located in Williamsburg, Kentucky, with an enrollment of approximately 3,200 students...

) in Williamsburg, Kentucky

Williamsburg, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 5,143 people, 1,928 households, and 1,127 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,102.5 people per square mile . There were 2,118 housing units at an average density of 454.0 per square mile...

, and distinguished himself in the debating society. He was also interested in sports, playing halfback

Halfback (American football)

A halfback, sometimes referred to as a tailback, is an offensive position in American football, which lines up in the backfield and generally is responsible for carrying the ball on run plays. Historically, from the 1870s through the 1950s, the halfback position was both an offensive and defensive...

on the football

American football

American football is a sport played between two teams of eleven with the objective of scoring points by advancing the ball into the opposing team's end zone. Known in the United States simply as football, it may also be referred to informally as gridiron football. The ball can be advanced by...

team and left field

Left fielder

In baseball, a left fielder is an outfielder who plays defense in left field. Left field is the area of the outfield to the left of a person standing at home plate and facing towards the pitcher's mound...

on the baseball team.

On June 24, 1898, Morrow enlisted as a private

Private (rank)

A Private is a soldier of the lowest military rank .In modern military parlance, 'Private' is shortened to 'Pte' in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and to 'Pvt.' in the United States.Notably both Sir Fitzroy MacLean and Enoch Powell are examples of, rare, rapid career...

in the 4th Kentucky Infantry Regiment for service in the Spanish–American War. He was first stationed at Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

, and later trained at Anniston, Alabama

Anniston, Alabama

Anniston is a city in Calhoun County in the state of Alabama, United States.As of the 2000 census, the population of the city is 24,276. According to the 2005 U.S. Census estimates, the city had a population of 23,741...

. Due to a bout with typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

, he never saw active duty, and mustered out as a second lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

on February 12, 1899. In 1900, he matriculated for the fall semester at the University of Cincinnati Law School. He graduated with a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws

The Bachelor of Laws is an undergraduate, or bachelor, degree in law originating in England and offered in most common law countries as the primary law degree...

degree in 1902.

Morrow opened his practice in Lexington. He established his reputation in one of his first cases—the trial of William Moseby, a black man accused of murder. Moseby's first trial had ended in a hung jury

Hung jury

A hung jury or deadlocked jury is a jury that cannot, by the required voting threshold, agree upon a verdict after an extended period of deliberation and is unable to change its votes due to severe differences of opinion.- England and Wales :...

, but because the evidence against him included a confession (which he later recanted), most observers believed he would be convicted in his second trial. Unable to find a defense lawyer for Moseby, the judge in the case turned to Morrow, who as a young lawyer was eager for work. Morrow proved that his client's testimony had been extorted; he had been told that a lynch mob waited outside the jail for him, but no such mob had ever existed. Morrow further showed that other testimony against his client was false. Moseby was acquitted September 21, 1902.

Morrow returned to Somerset in 1903. There, he married Katherine Hale Waddle on June 18, 1903. Waddle's father had studied law under Morrow's father, and Edwin and Katherine had been playmates, schoolmates, and later sweethearts. The couple had two children, Edwina Haskell in July 1904 and Charles Robert in November 1908.

Political career

In 1904, Morrow was appointed city attorneyCity attorney

A city attorney can be an elected or appointed position in city and municipal government in the United States. The city attorney is the attorney representing the city or municipality....

for Somerset, serving until 1908. President William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

appointed him U.S. District Attorney

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

for the Eastern District of Kentucky

United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky is the Federal district court whose jurisdiction comprises approximately the Eastern half of the state of Kentucky....

in 1910. He continued in this position until he was removed from office by President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

in 1913.

William S. Taylor

William Sylvester Taylor was the 33rd Governor of Kentucky. He was initially declared the winner of the disputed gubernatorial election of 1899, but the Kentucky General Assembly reversed the election results, giving the victory to his opponent, William Goebel...

offered to make Morrow his Secretary of State in exchange for Bradley's support in the election; Bradley refused. Despite the encouragement of friends, Morrow declined to run for governor in 1911.

In 1912, Morrow was chosen as the Republican candidate for the Senate seat of Thomas Paynter. Paynter had decided not to seek re-election, and the Democrats nominated Ollie M. James

Ollie M. James

Ollie Murray James , a Democrat, represented Kentucky in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate.-Biography:...

of Crittenden County

Crittenden County, Kentucky

Crittenden County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky.It was formed in 1842. As of 2000, the population was 9,384. Its county seat is Marion. The county is named for John J. Crittenden who was Governor of Kentucky 1848-1850...

. The General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

was heavily Democratic and united behind James. On a joint ballot, James defeated Morrow by a vote of 105–28. Due to the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment

Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution established direct election of United States Senators by popular vote. The amendment supersedes Article I, § 3, Clauses 1 and 2 of the Constitution, under which senators were elected by state legislatures...

the next year, this was the last time the Kentucky legislature would elect a senator.

At the state Republican convention in Lexington on June 15, 1915, Morrow was chosen as the Republican candidate for governor over Latt F. McLaughlin. His Democratic

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

opponent was his close friend, Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus O. Stanley

Augustus Owsley Stanley I was a politician from the US state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 38th Governor of Kentucky and also represented the state in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate...

. Morrow charged previous Democratic administrations with corruption and called for the election of a Republican because "You cannot clean house with a dirty broom." Both men ran on progressive platforms, and the election went in Stanley's favor by only 471 votes. Although it was the closest gubernatorial vote in the state's history, Morrow refused to challenge the results, which greatly increased his popularity. His decision was influenced by the fact that a challenge would be decided by the General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

, which had a Democratic majority in both houses.

Governor of Kentucky

Morrow served as a delegate to the Republican National ConventionRepublican National Convention

The Republican National Convention is the presidential nominating convention of the Republican Party of the United States. Convened by the Republican National Committee, the stated purpose of the convocation is to nominate an official candidate in an upcoming U.S...

in 1916

1916 Republican National Convention

The 1916 Republican National Convention was held in Chicago, Illinois at the Chicago Coliseum, from June 7 to June 10, 1916. It nominated Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes of New York for president and former Vice President Charles Fairbanks of Indiana for a return to the vice presidency....

, 1920

1920 Republican National Convention

The 1920 National Convention of the Republican Party of the United States nominated Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding for President and Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge for Vice President...

, and 1928

1928 Republican National Convention

The 1928 National Convention of the Republican Party of the United States was held at Convention Hall in Kansas City, Missouri, from June 12 to June 15, 1928....

. In 1919, he was chosen by acclamation as his party's candidate for governor. This time, his opponent was James D. Black

James D. Black

James Dixon Black was the 39th Governor of Kentucky, serving for seven months in 1919. He ascended to the office when Governor Augustus O. Stanley was elected to the U.S. Senate....

. Black was Stanley's lieutenant governor

Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky

The office of lieutenant governor of Kentucky has existed under the last three of Kentucky's four constitutions, beginning in 1797. The lieutenant governor serves as governor of Kentucky under circumstances similar to the Vice President of the United States assuming the powers of the presidency...

and had ascended to the governorship in May 1919 when Stanley resigned to take a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Morrow encouraged the state's voters to "Right the Wrong of 1915". He again ran on a progressive platform, advocating an amendment to the state constitution

Kentucky Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more...

to grant women's suffrage. His support was not as strong for a prohibition

Prohibition in the United States

Prohibition in the United States was a national ban on the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, in place from 1920 to 1933. The ban was mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Volstead Act set down the rules for enforcing the ban, as well as defining which...

amendment. He attacked the Stanley–Black administration as corrupt. Days before the election, he exposed a contract awarded by the state Board of Control to a non-existent company. Historian Lowell H. Harrison

Lowell H. Harrison

Lowell Hayes Harrison was an American historian specializing in Kentucky. Harrison graduated from College High . He received a B.A. from Western Kentucky University in 1946, then enrolled at New York University where he earned an M.A. in 1947 and a PhD in 1951, both in history...

opined that Black's refusal to remove the members of the board following this revelation probably sealed his defeat. Morrow won the general election by more than 40,000 votes. It was the largest margin of victory for a Republican gubernatorial candidate in the state's history.

On January 6, 1920, Governor Morrow signed the bill ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment

Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits any United States citizen to be denied the right to vote based on sex. It was ratified on August 18, 1920....

, making Kentucky the 23rd state to ratify it, and the moment is captured in a photograph with members of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association

Kentucky Equal Rights Association

Kentucky Equal Rights Association was the first permanent statewide women's rights organization in Kentucky. Founded in November 1888, the KERA voted in 1920 to transmute itself into the to continue its many and diverse progressive efforts on behalf of women's rights.Inspired by Lucy Stone during...

. During the 1920 legislative session, the Republicans held a majority in the state House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

and were a minority by only two votes in the state Senate

Kentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators...

. During the session, Morrow was often able to convince C. W. Burton, a Democratic senator from Grant County

Grant County, Kentucky

Grant County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It was formed in 1820. As of 2000, the population was 22,384. Its county seat is Williamstown...

, to support Republican proposals. Tie votes in the Senate were broken by Republican lieutenant governor S. Thruston Ballard

S. Thruston Ballard

Samuel Thruston Ballard was an American politician, who served as the Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky from 1919 to 1923, under Governor Edwin P. Morrow.-External links:...

. Consequently, Morrow was able to effect a considerable reorganization of the state government, including replacing the Board of Control with a nonpartisan Board of Charities and Corrections, centralizing highway works, and revising property taxes. He oversaw improvements to the education system, including better textbook selection and a tax on racetracks to support a minimum salary for teachers. Among Morrow's reforms that did not pass was a proposal to make the judiciary

Judiciary

The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary also provides a mechanism for the resolution of disputes...

nonpartisan.

Morrow urged enforcement of state laws against carrying concealed weapons and restricted activities of the Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

. During his first year in office, he granted only 100 pardons. This was a considerable decrease from the number granted by his immediate predecessors. During their first years in office, J. C. W. Beckham

J. C. W. Beckham

John Crepps Wickliffe Beckham was the 35th Governor of Kentucky and a United States Senator from Kentucky...

granted 350 pardons, James B. McCreary

James B. McCreary

James Bennett McCreary was a lawyer and politician from the US state of Kentucky. He represented the state in both houses of the U.S. Congress and served as its 27th and 37th governor...

(during his second stint as governor) granted 139, and Augustus O. Stanley granted 257. He was also an active member of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation

Commission on Interracial Cooperation

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation was formed in the U.S. South in 1919 in the aftermath of violent race riots that occurred the previous year in several southern cities. The organization worked to oppose lynching, mob violence, and peonage and to educate white southerners concerning the...

, a society for the elimination of racial violence in the South.

Kentucky National Guard

The Kentucky National Guard consists of the:*Kentucky Army National Guard*Kentucky Air National Guard-External links:** compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History...

to Lexington to protect Will Lockett, a black World War I veteran on trial for murder. Morrow told the state adjutant general

Adjutant general

An Adjutant General is a military chief administrative officer.-Imperial Russia:In Imperial Russia, the General-Adjutant was a Court officer, who was usually an army general. He served as a personal aide to the Tsar and hence was a member of the H. I. M. Retinue...

"Do as much as you have to do to keep that negro in the hands of the law. If he falls into the hands of the mob I do not expect to see you alive." Lockett had already confessed, without the benefit of a lawyer, to the murder. His trial took only thirty minutes as he pleaded guilty but asked for a life sentence instead of death. Despite his plea, he was sentenced to die in the electric chair.

A crowd of several thousand gathered outside the courthouse while Lockett's trial was underway. A cameraman asked a large group of those gathered to shake their fists and yell so he could get a picture. The rest of the crowd mistakenly believed they were storming the courthouse and rushed forward. In the ensuing skirmish, one policeman was injured so badly that his arm later had to be amputated. The National Guard opened fire, killing six people and wounding approximately fifty. Some members of the mob looted nearby stores in search of weapons to retaliate, but reinforcements arrived from a nearby army post by mid-afternoon. Martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

was declared, and no further violence was perpetrated. A month later, Lockett was executed at the Kentucky State Penitentiary

Kentucky State Penitentiary

The Kentucky State Penitentiary, also known as the "Castle on the Cumberland," is a prison of the Kentucky Department of Corrections located in Eddyville, Kentucky. The state's only maximum security male facility, the prison is located on Lake Barkley on the Cumberland River, about from downtown...

in Eddyville

Eddyville, Kentucky

Eddyville is a city in Lyon County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,350 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Lyon County . The Kentucky State Penitentiary is located in Eddyville.-History:...

.

The incident is believed to be the first forceful suppression of a lynch mob by state and local officials in the South

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

. Morrow received a laudatory telegram from the NAACP

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

, and most of the national press regarding the incident was favorable. W. E. B. Du Bois called it the "Second Battle of Lexington

Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. They were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, Lincoln, Menotomy , and Cambridge, near Boston...

". Morrow was consistent in his use of state troops to end violence in the state. In 1922, he again dispatched the National Guard to quell a violent mill strike in Newport

Newport, Kentucky

Newport is a city in Campbell County, Kentucky, United States, at the confluence of the Ohio and Licking rivers. The population was 15,273 at the 2010 census. Historically, it was one of four county seats of Campbell County. Newport is part of the Greater Cincinnati, Ohio Metro Area which...

.

Morrow also demanded consistency from local law enforcement officials. In 1921, he removed the Woodford County

Woodford County, Kentucky

Woodford County is a county located in the heart of the Bluegrass region of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 23,208. Its county seat is Versailles. The county is named for General William Woodford, who was with General George Washington at Valley Forge...

jailer from office because he allowed a black inmate to be lynched and offered a reward of $25,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the perpetrators. Citizens of Versailles

Versailles, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 7,511 people, 3,160 households, and 2,110 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 3,330 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 88.18% White, 8.67% African American, 0.15% Native American, 0.35%...

were more outraged that the jailer had been removed from office than that the prisoner had been lynched. The locals refused to aid in the investigation, and the lynchers were never arrested or charged. Local officials appointed the jailer's wife to finish his term in an attempt to skirt the removal.

In August 1922, a traveling salesman named Jack Eaton was arrested for allegedly assault

Assault

In law, assault is a crime causing a victim to fear violence. The term is often confused with battery, which involves physical contact. The specific meaning of assault varies between countries, but can refer to an act that causes another to apprehend immediate and personal violence, or in the more...

ing several young girls. The girls' parents refused to press charges, and Eaton was released. Later, he was captured by a mob, who cut him several times and poured turpentine into his wounds. An investigation found that the Scott County

Scott County, Kentucky

Scott County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. The population was 47,173 in the 2010 Census. Its county seat is Georgetown.Scott County is part of the Lexington–Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

sheriff

Sheriffs in the United States

In the United States, a sheriff is a county official and is typically the top law enforcement officer of a county. Historically, the sheriff was also commander of the militia in that county. Distinctive to law enforcement in the United States, sheriffs are usually elected. The political election of...

had willfully delivered Eaton to the mob, and Morrow removed him from office. Though Eaton was a white man, blacks were elated with the removal because they hoped it would encourage other jailers to step up efforts to protect against lynchings and mob violence.

Morrow was frequently mentioned as a potential candidate for vice president

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

in 1920, but he withdrew his name from consideration, sticking to a campaign promise not to seek a higher office while governor. On July 27, 1920, he made a speech in Northampton

Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population of Northampton's central neighborhoods, was 28,549...

, Massachusetts, officially notifying Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

of his nomination for that office. Although he supported Frank O. Lowden for president, the nomination went to Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding was the 29th President of the United States . A Republican from Ohio, Harding was an influential self-made newspaper publisher. He served in the Ohio Senate , as the 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio and as a U.S. Senator...

, and Morrow campaigned vigorously on behalf of his party's ticket.

In his address to the 1922 legislature, Morrow asked for for improvements to the state highway system and for the repeal of all laws denying equal rights to women. He also recommended a large bond

Government bond

A government bond is a bond issued by a national government denominated in the country's own currency. Bonds are debt investments whereby an investor loans a certain amount of money, for a certain amount of time, with a certain interest rate, to a company or country...

issue to finance improvements to the state's universities, schools, prisons, and hospitals. By this time, however, the Republicans had surrendered their majority in the state House, and practically all of Morrow's proposals were voted down. Morrow countered by vetoing several Democratic bills, including $700,000 in appropriations. Among the few accomplishments of the 1922 legislature were passage of an anti-lynching law, the abolition of convict labor

Penal labour

Penal labour is a form of unfree labour in which prisoners perform work, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence which involve penal labour include penal servitude and imprisonment with hard labour...

and the establishment of normal schools at Murray

Murray, Kentucky

Murray is a city in Calloway County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 17,741 at the 2010 census and has a micropolitan area population of 37,191. It is the 22nd largest city in Kentucky...

and Morehead

Morehead, Kentucky

As of the census of 2010, there were 6,845 people, households, and families residing in the city. The population density was 726.2 people per square mile. There were 2,356 housing units at an average density of 253.3 per square mile. The racial makeup of the city was 93.2% White, 3.2% African...

. Today, these schools are Murray State University

Murray State University

Murray State University, located in the city of Murray, Kentucky, is a four-year public university with approximately 10,400 students. The school is Kentucky’s only public university to be listed in the U.S.News & World Report regional university top tier for the past 20 consecutive years...

and Morehead State University

Morehead State University

Morehead State University is a public, co-educational university located in Morehead, Kentucky, United States in the foothills of the Daniel Boone National Forest in Rowan County, midway between Lexington, Kentucky, and Huntington, West Virginia. The 2012 edition of "America's Best Colleges" by U.S...

, respectively. The 1922 legislature also established a commission to govern My Old Kentucky Home State Park

My Old Kentucky Home State Park

My Old Kentucky Home State Park is a state park located in Bardstown, Kentucky. The park's centerpiece is Federal Hill, a former plantation built by United States Senator John Rowan in 1795. During Rowan's life, the mansion became a meeting place for local politicians and hosted several visiting...

and approved construction of the Jefferson Davis Monument

Jefferson Davis State Historic Site

-External links:***...

.

Despite the fact that Morrow gained national praise for his handling of the Lockett trial, historian James Klotter opined that he "left behind a solid, and rather typical, record for a Kentucky governor." He cited Morrow's fiscal conservatism and inability to control the legislature in 1922 as reasons for his lackluster assessment, although he praised Morrow's advancement of racial equality in the state. Morrow was prohibited by the state constitution from seeking a second consecutive term, and the achievements of his administration were not significant enough to ensure the election of Charles I. Dawson

Charles I. Dawson

Charles I. Dawson was a lawyer and politician from Kentucky who ran several high profile campaigns as the nominee of the Republican party, and served for ten years as a United States federal judge....

, his would-be Republican successor in the gubernatorial election of 1923.

Later career and death

Following his term as governor, Morrow retired to Somerset where he became active in the Watchmen of the Republic, an organization devoted to the eradication of prejudice and the promotion of tolerance. He served on the United States Railroad Labor Board from 1923 to 1926 and its successor, the Railway Mediation Board, from 1926 to 1934. He resigned to run for a seat in the U.S. House of RepresentativesUnited States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

representing the Ninth District

Kentucky's 9th congressional district

United States House of Representatives, Kentucky District 9 was a district of the United States Congress in Kentucky. It was lost to redistricting in 1953. Its last Representative was James S. Golden.-List of representatives:-References:*...

, but lost his party's nomination to John M. Robsion

John M. Robsion

John Marshall Robsion , a Republican, represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives....

.

Following his defeat in the congressional primary, Morrow made plans to return to Lexington to resume his law practice. On June 15, 1935, he died unexpectedly of a heart attack while temporarily living with a cousin in Frankfort

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

. He is buried in Frankfort Cemetery

Frankfort Cemetery

The Frankfort Cemetery is located on East Main Street in Frankfort, Kentucky. The cemetery is the burial site of Daniel Boone and contains the graves of other famous Americans including seventeen Kentucky governors.-History:...

.

Ancestors

External links

- Pulaski County Historical Fact Book II, Chapter Nine, Biographical Sketches. Published by Somerset Community College.

- Kentucky Governors 1907–1927

- Political Graveyard