Decompression (diving)

Encyclopedia

Underwater diving

Underwater diving is the practice of going underwater, either with breathing apparatus or by breath-holding .Recreational diving is a popular activity...

derives from the reduction in ambient pressure

Ambient pressure

The ambient pressure on an object is the pressure of the surrounding medium, such as a gas or liquid, which comes into contact with the object....

experienced by the diver during the ascent at the end of a dive or hyperbaric exposure and refers to both the reduction in pressure and the process of allowing dissolved inert gases to be eliminated from the tissues during decompression. These gases can form bubbles in the tissues of the diver if the concentration gets too high and the bubbles can cause damage to tissues known as decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

or the bends. The immediate goal of planned decompression is to avoid presentation of symptoms of bubble formation in the tissues of the diver and the long term goal is to also avoid complications due to sub-clinical decompression injury.

The symptoms of decompression sickness are known to be caused by damage resulting from the formation and growth of bubbles of inert gas within the tissues and by blockage of arterial blood supply to tissues by gas bubbles and other emboli consequential to bubble damage.

The precise mechanisms of bubble formation and the damage they cause has been the subject of medical research for a considerable time and several hypotheses have been advanced and tested. Tables and algorithms for predicting the outcome of hyperbaric exposures have been proposed, tested and used, and usually found to be of some use but not entirely reliable. Decompression remains a procedure with some risk, but this has been reduced and is generally considered to be acceptable for dives within the well tested range of recreational diving.

Divers breathing gas

Breathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

at high pressure

Pressure

Pressure is the force per unit area applied in a direction perpendicular to the surface of an object. Gauge pressure is the pressure relative to the local atmospheric or ambient pressure.- Definition :...

may need to do decompression stops. A diver who breathes gas at atmospheric pressure such as in free-diving

Free-diving

Freediving is any of various aquatic activities that share the practice of breath-hold underwater diving. Examples include breathhold spear fishing, freedive photography, apnea competitions and, to a degree, snorkeling...

, snorkeling

Snorkeling

Snorkeling is the practice of swimming on or through a body of water while equipped with a diving mask, a shaped tube called a snorkel, and usually swimfins. In cooler waters, a wetsuit may also be worn...

or when using an atmospheric diving suit

Atmospheric diving suit

An atmospheric diving suit or ADS is a small one-man articulated submersible of anthropomorphic form which resembles a suit of armour, with elaborate pressure joints to allow articulation while maintaining an internal pressure of one atmosphere...

does not usually need to do decompression stops. However, it is possible to get taravana

Taravana

Taravana is a disease often found among Polynesian island natives who habitually dive deep without breathing apparatus many times in close succession, usually for food or pearls. These free-divers may make 40 to 60 dives a day, each of 30 or 40 metres .Taravana seems to be decompression sickness....

from repetitive deep free-diving

Free-diving

Freediving is any of various aquatic activities that share the practice of breath-hold underwater diving. Examples include breathhold spear fishing, freedive photography, apnea competitions and, to a degree, snorkeling...

with short surface intervals.

During a decompression stop, the venous microbubbles present after most dives leave the diver's body safely through the lung

Lung

The lung is the essential respiration organ in many air-breathing animals, including most tetrapods, a few fish and a few snails. In mammals and the more complex life forms, the two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of the heart...

s. If they are not given enough time to leave safely or more bubbles are created than can be eliminated naturally, the bubbles grow in size and number causing the symptoms and injuries of decompression sickness.

When diving with nitrogen

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element that has the symbol N, atomic number of 7 and atomic mass 14.00674 u. Elemental nitrogen is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, and mostly inert diatomic gas at standard conditions, constituting 78.08% by volume of Earth's atmosphere...

-based breathing gas

Breathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

es, decompression stops are typically carried out in the 3 to 20 m (9.8 to 65.6 ft) depth range. With helium

Helium

Helium is the chemical element with atomic number 2 and an atomic weight of 4.002602, which is represented by the symbol He. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas that heads the noble gas group in the periodic table...

-based breathing gases the stop depths may be between 20 and 40 m (65.6 and 131.2 ft).

The length of "surface interval" between dives is also very important for decompression. It typically takes from 16 to 24 hours for the body to return to its normal atmospheric levels of inert gas saturation after a dive. The surface interval can be thought of as the last decompression stop of a dive.

Physics and physiology of decompression

Decompression involves a complex interaction of gas solubility, partial pressures and concentration gradients, bulk transport and bubble mechanics in living tissues.Some of the factors influencing inert gas uptake and elimination in living tissues are:

Solubility

SolubilitySolubility

Solubility is the property of a solid, liquid, or gaseous chemical substance called solute to dissolve in a solid, liquid, or gaseous solvent to form a homogeneous solution of the solute in the solvent. The solubility of a substance fundamentally depends on the used solvent as well as on...

is the property of a gas, liquid or solid substance (the solute) to be held homogeneously dispersed as molecules or ions in a liquid or solid medium (the solvent).

In decompression theory the solubility of gases in liquids is of primary importance.

Solubility of gases in liquids is influenced by three main factors:

- The nature of the solvent liquid and the solute gas

- Temperature (gases are less soluble in water at higher temperatures, but may be more soluble in organic solvents)

- PressurePressurePressure is the force per unit area applied in a direction perpendicular to the surface of an object. Gauge pressure is the pressure relative to the local atmospheric or ambient pressure.- Definition :...

(solubility of a gas in a liquid is proportional to the partial pressurePartial pressureIn a mixture of ideal gases, each gas has a partial pressure which is the pressure which the gas would have if it alone occupied the volume. The total pressure of a gas mixture is the sum of the partial pressures of each individual gas in the mixture....

of the gas on the liquid - Henry's LawHenry's lawIn physics, Henry's law is one of the gas laws formulated by William Henry in 1803. It states that:An equivalent way of stating the law is that the solubility of a gas in a liquid at a particular temperature is proportional to the pressure of that gas above the liquid...

) - Presence of other solutes in the solvent

Diffusion

DiffusionDiffusion

Molecular diffusion, often called simply diffusion, is the thermal motion of all particles at temperatures above absolute zero. The rate of this movement is a function of temperature, viscosity of the fluid and the size of the particles...

is the movement of molecules or ions in a medium when there is no gross mass flow of the medium.

Diffusion can occur in gases, liquids or solids, or any combination.

Diffusion is driven by the kinetic energy of the diffusing molecules - it is faster in gases and slower in solids when compared with liquids due to the variation in distance between collisions and diffusion is faster when the temperature is higher as the average energy of the molecules is greater. Diffusion is also faster in smaller, lighter molecules of which helium is the extreme example.

In decompression theory the diffusion of gases, particularly when dissolved in liquids, is of primary importance.

Partial pressure gradient

Also known as concentration gradient, this can be used as a model for the driving mechanism of diffusion.The partial pressure gradient is the variation of partial pressure (or more accurately, the concentration) of the solute (dissolved gas) from one point to another in the solvent. The solute molecules will randomly collide with the other molecules present, and tend over time to spread out until the distribution is statistically uniform. This has the effect that molecules will diffuse from regions of higher concentration (partial pressure) to regions of lower concentration, and the rate of diffusion is proportional to the rate of change of the concentration. Molecules of solute will also tend to aggregate in areas of greater solubility in a non-homogenous solvent medium.

Inert gas uptake

In this context, inert gas refers to a gas which is not metabolically activeMetabolism

Metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolism is usually divided into two categories...

. Atmospheric nitrogen

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element that has the symbol N, atomic number of 7 and atomic mass 14.00674 u. Elemental nitrogen is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, and mostly inert diatomic gas at standard conditions, constituting 78.08% by volume of Earth's atmosphere...

(N2) is the most common example. Helium

Helium

Helium is the chemical element with atomic number 2 and an atomic weight of 4.002602, which is represented by the symbol He. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas that heads the noble gas group in the periodic table...

(He) is the other inert gas commonly used in breathing mixtures for divers.

Atmospheric nitrogen has a partial pressure of approximately 0.78bar. Air in the alveoli is diluted by saturated water vapour (H2O) and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a naturally occurring chemical compound composed of two oxygen atoms covalently bonded to a single carbon atom...

(CO2), given off by the blood as a metabolic product and contains less oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

(O2) as some of it is taken up by the blood for metabolic use and the resulting partial pressure of nitrogen is about 0,758bar

At atmospheric pressure the body tissues

Tissue (biology)

Tissue is a cellular organizational level intermediate between cells and a complete organism. A tissue is an ensemble of cells, not necessarily identical, but from the same origin, that together carry out a specific function. These are called tissues because of their identical functioning...

are therefore normally saturated with nitrogen at 0.758bar (569mmHg).

At depth a diver’s lungs are filled with breathing gas at increased pressure.

The inert gases from the breathing gas in the lungs diffuses into blood in the alveolar capillaries ("moves down the pressure gradient") and is distributed around the body by the systemic circulation

Systemic circulation

Systemic circulation is the part of the cardiovascular system which carries oxygenated blood away from the heart to the body, and returns deoxygenated blood back to the heart. This physiologic theory of circulation was first described by William Harvey...

.

For example: At 10 meters sea water (msw) the partial pressure of nitrogen in air will be 1.58bar.

Perfusion

PerfusionPerfusion

In physiology, perfusion is the process of nutritive delivery of arterial blood to a capillary bed in the biological tissue. The word is derived from the French verb "perfuser" meaning to "pour over or through."...

is the mass flow of blood through the tissues. Dissolved materials are transported in the blood much faster than they would be distributed by diffusion alone (order of minutes compared to hours).

The dissolved gas in the alveolar blood is transported to the body tissues by the blood circulation. There it diffuses through the cell walls into the tissues, where it will eventually reach equilibrium.

The better the blood supply to a tissue the faster it will become saturated with gas at the new partial pressure.

Saturation and supersaturation

If the supply of gas to a solvent is unlimited, the gas will diffuse into the solvent until there is so much dissolved that the amount diffusing back out is equal to the amount diffusing in. This is called saturationSaturation (chemistry)

In chemistry, saturation has six different meanings, all based on reaching a maximum capacity...

.

If the external partial pressure of the gas (in the lungs) is then reduced, more gas will diffuse out than in. This is a condition known as supersaturation

Supersaturation

The term supersaturation refers to a solution that contains more of the dissolved material than could be dissolved by the solvent under normal circumstances...

. The gas will not necessarily form bubbles in the solvent at this stage.

Tissue compartments

Most decompression models work with slow and fast tissue compartments. These are imaginary tissues which are designated as fast and slow to describe the rate of saturation.Real tissues will also take more or less time to saturate, but the models do not need to use actual tissue values to produce a useful result. Models with from one to 16 tissue compartments with half times from 4 minutes to 635 minutes or more have been used to generate decompression tables.

For example: Tissues with a high lipid

Lipid

Lipids constitute a broad group of naturally occurring molecules that include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins , monoglycerides, diglycerides, triglycerides, phospholipids, and others...

content take up a larger amount of nitrogen, but often have a poor blood supply. These will take longer to reach equilibrium, and are described as slow, than tissues with a good blood supply and less capacity for dissolved gas, which are described as fast.

Tissue half times

Half time of a tissue is the time it takes for the tissue to become 50% saturated at a new partial pressure.For each consecutive half time the tissue will become half again saturated in the sequence ½, ¾, 7/8, 15/16 etc.

A 5 minute tissue will be 50% saturated in 5 minutes, 75% in 10 minutes, 87.5% in 15 minutes and for practical purposes, saturated in about 30 minutes (6 half times =>63/64 saturated)

Tissue compartment half times range from 5 minutes to about 750 minutes in current decompression models

Saturated tissues

Gas remains in the tissue in dissolved form until the partial pressure of that gas in the lungs is reduced.A lower partial pressure in the lungs will result in more gas diffusing out into the lungs and less into the blood.

As the pressure reduces, the diffusion will reach a state where more gas diffuses into the lungs than into the blood.

Inherent unsaturation

There is a metabolic reduction of total gas pressure in the tissues.The sum of partial pressures of the air that the diver breathes must necessarily balance with the sum of partial pressures in the lung gas. In the alvoeli the gas has been humidified by a partial pressure of approximately 63mbar (47mmHg) and has also gained about 55mbar (41mmHg) carbon dioxide from the venous blood. Oxygen has also diffused into the arterial blood, reducing the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli by about 67mbar(50mmHg) As the total pressure in the alveoli must balance with the ambient pressure, this dilution results in an effective partial pressure of nitrogen of about 758mb (569mmHg) (surface values).

At a steady state, when the tissues have been saturated by the inert gases of the breathing mixture, metabolic processes reduce the partial pressure of the less soluble oxygen and replace it with carbon dioxide, which is considerably more soluble in water. In the cells of a typical tissue, the partial pressure of oxygen will drop to around 13mbar (10mmHg), while the partial pressure of carbon dioxide will be about 65mbar (49mmHg). The sum of these partial pressures (water, oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen) comes to roughly 900mbar (675mmHg), which is some 113mbar (85mmHg) less than the total pressure of the respiratory gas. This is a significant saturation deficit, and it provides a buffer against supersaturation and a driving force for dissolving bubbles.

This saturation deficit is also referred to as the "Oxygen window

Oxygen window in technical diving

In diving, the oxygen window is the difference between the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood and the ppO2 in body tissues. It is caused by metabolic consumption of oxygen.The term "oxygen window" was first used by Albert R. Behnke in 1967...

".

Supersaturated tissues

When the gas in a tissue is at a concentration where more diffuses out then in it is called supersaturated and starts degassing: dissolved gas diffuses into the bloodstream and out of the system via the lungs.If the ambient pressure is too low, bubbles may form in the tissues.

Outgassing

For optimised decompression the driving force for tissue desaturation should be kept at a maximum, provided that this does not cause symptomatic tissue injury due to bubble formation and growth (symptomatic decompression sickness).There are two fundamentally different ways this has been approached. The first is based on an assumption that there is a level of supersaturation which does not produce symptomatic bubble formation and is based on empirical observations of the maximum decompression which does not result in an unacceptable rate of symptoms. This approach seeks to maximise the concentration gradient providing there are no symptoms. The second assumes that bubbles will form at any level of supersaturation where the total gas tension in the tissue is greater than the ambient pressure and that bubbles are eliminated more slowly than dissolved gas.

Critical ratio model

J.S. Haldane originally used a pressure ratio of 2 to 1 for decompression on the principle that the saturation of the body should at no time be allowed to exceed about double the air pressure.

This principle was applied as a pressure ratio of total ambient pressure and did not take into account the partial pressures of the component gases of the breathing air. His experimental work on goats and observations of human divers appeared to support this assumption. However, in time, this was found to be inconsistent with incidence of decompression sickness and changes were made to the initial assumptions.

This was later changed to a 1.58:1 ratio of nitrogen partial pressures.

Critical difference models

Further research by people such as Robert Workman suggested that the criteria was not the ratio of pressures, but the actual pressure differentials. Applied to Haldane's work, this would suggest that the limit is not determined by the 1.58:1 ratio but rather by the difference of 0.58 atmospheres between tissue pressure and ambient pressure. Most tables today, including the Buhlmann tables, are based on the critical difference model.

M-values

At a given ambient pressure, the M-value is the maximum value of absolute inert gas pressure that a tissue compartment can take without presenting symptoms of decompression sickness. M-values are limits for the tolerated gradient between inert gas pressure and ambient pressure in each compartment.

Alternative terminology for M-values include "supersaturation limits", "limits for tolerated overpressure", and "critical tensions".

The no-supersaturation approach

According to the thermodynamic model of LeMessurier and Hills, this condition of optimum driving force for outgassing is satisfied when the hydrostatic pressure is just sufficient to prevent phase separation (bubble formation).The fundamental difference of this approach is equating absolute ambient pressure with the total of the partial gas tensions in the tissue for each gas after decompression as the limiting point beyond which bubble formation is expected.

The model assumes that the natural unsaturation in the tissues due to metabolic reduction in oxygen partial pressure provides the buffer against bubble formation, and that the tissue may be safely decompressed provided that the reduction in ambient pressure does not exceed this unsaturation value. Clearly any method which increases the unsaturation would allow faster decompression, as the concentration gradient would be greater without risk of bubble formation.

The natural unsaturation increases with depth, so a larger ambient pressure differential is possible at greater depth, and reduces as the diver surfaces. This model leads to slower ascent rates and deeper first stops, but shorter shallow stops, as there is less (none?) bubble phase gas to be eliminated.

Bubble mechanics

Equilibrium of forces on the surface is required for a bubble to exist.These are:

- Ambient pressureAmbient pressureThe ambient pressure on an object is the pressure of the surrounding medium, such as a gas or liquid, which comes into contact with the object....

, exerted on the outside of the surface, acting inwards - Pressure due to tissue distortion, also on the outside and acting inwards

- Surface tensionSurface tensionSurface tension is a property of the surface of a liquid that allows it to resist an external force. It is revealed, for example, in floating of some objects on the surface of water, even though they are denser than water, and in the ability of some insects to run on the water surface...

of the liquid at the interface between the bubble and the surroundings. This is along the surface of the bubble, so the resultant acts towards the centre of curvature. This will tend to squeeze the bubble, and is more severe for small bubbles as it is an inverse function of the radius. - The resulting forces must be balanced by the pressure on the inside of the bubble. This is the sum of the partial pressures of the gases inside due to the net diffusion of gas to and from the bubble.

If the solvent outside the bubble is saturated or unsaturated, the partial pressure will be less than in the bubble, and the surface tension will be squeezing the gas out of the bubble, and the smaller the bubble the faster it will get squeezed out. A gas bubble can only grow at constant pressure if the surrounding solvent is sufficiently supersaturated to overcome the surface tension.

Bubbles that are sufficiently small will collapse due to surface tension if the supersaturation is low.

Bubble nucleation

Bubble formation occurs in the blood or other tissues, possibly in crevices in macromolecules.A solvent can carry a supersaturated load of gas in solution. Whether it will come out of solution in the bulk of the solvent will depend on a number of factors.

Something which reduces surface tension, or adsorbs gas molecules, or locally reduces solubility of the gas or causes a local reduction in static pressure in a fluid may result in a bubble nucleation or growth.

This may include velocity changes and turbulence in fluids and local tensile loads in solids and semi-solids.

Lipids and other hydrophobic surfaces may reduce surface tension (blood vessel walls may have this effect)

Dehydration may reduce gas solubility in a tissue due to higher concentration of other solutes, and less solvent to hold the gas.

Bubble growth

Once a micro bubble forms it may continue to grow if the tissues are still supersaturated. As the bubble grows it may distort the surrounding tissue and cause damage to cells and pressure on nerves resulting in pain.If a bubble or an object exists which collects gas molecules this may reach a size where the internal pressure exceeds the combined surface tension and external pressure and the bubble will grow.

If the solvent is sufficiently supersaturated, the diffusion of gas into the bubble will exceed the rate at which it diffuses back into solution.

If this excess pressure is greater than the pressure due to surface tension the bubble will grow.

When a bubble grows, the surface tension decreases, and the interior pressure drops, allowing gas to diffuse in faster, and diffuse out slower, so the bubble grows or shrinks in a positive feedback situation.

The growth rate is reduced as the bubble grows by the fact that the surface area increases as the square of the radius, while the volume increases as the cube of the radius.

If the external pressure is reduced (due to reduced hydrostatic pressure during ascent, for example) the bubble will also grow.

Silent bubbles

Decompression bubbles appear to form mostly in the capillaries where the gas concentration is highest, often those feeding the veins draining the active limbs.They do not generally form in the arteries, as arterial blood has recently had the opportunity to release excess gas into the lungs.

Bubbles which are carried back to the heart in the veins will normally find their way to the right side of the heart, and from there they will normally enter the pulmonary circulation and eventually pass through or be trapped in the capillaries of the lungs, which are around the alveoli and very near to the respiratory gas, where they will diffuse from the bubbles though the capillary and alveolar walls into the gas in the lung. The bubbles which are small enough to pass through the lung capillaries are generally small enough to be dissolved again due to a combination of surface tension and diffusion to a lowered concentration in the surrounding blood.

If the number of lung capillaries blocked by these bubbles is relatively small, the diver will not display symptoms, and no tissue will be damaged (lung tissues are adequately oxygenated by diffusion).

Bubbles which cause no noticeable effects are known as silent bubbles.

Decompression illness and injuries

Problems due to vascular decompression bubbles

Bubbles may be trapped in the lung capillaries, temporarily blocking them. If this is severe, the symptom called "chokes" may occur.If the diver has a patent foramen ovale (or a shunt in the pulmonary circulation), bubbles may pass through it and bypass the pulmonary circulation to enter the arterial blood. If these bubbles are not absorbed in the arterial plasma and lodge in systemic capillaries they will block the flow of oxygenated blood to the tissues supplied by those capillaries, and those tissues will be starved of oxygen. Moon and Kisslo concluded that "the evidence suggests that the risk of serious neurological DCI or early onset DCI is increased in divers with a resting right-to-left shunt through a PFO. There is, at present, no evidence that PFO is related to mild or late onset bends."

Extravascular bubbles

Bubbles form within other tissues as well as the blood vessels.Inert gas can diffuse into bubble nuclei between tissues. In this case, the bubbles can distort and permanently damage the tissue. As they grow, the bubbles may also compress nerves as they grow causing pain.

Extravascular bubbles usually form in slow tissues such as joints, tendons and muscle sheaths.

Direct expansion causes tissue damage, with the release of histamines and their associated affects.

Decompression models

A fundamental problem in the design of decompression tables is that the rules that govern a single dive and ascent do not apply when some tissue bubbles already exist, as these will delay inert gas elimination and equivalent decompression may result in decompression sickness.A solution was the development of multi-tissue models, which assumed that different parts of the body absorbed gas at different rates. Each tissue, or compartment, has a different half-life. Fast tissues absorb gas relatively quickly, but will release it quickly during ascent. A fast tissue may become saturated in the course of a normal sports dive, while a slow tissue may hardly have absorbed any gas. By calculating the levels in each compartment separately, researchers are able to construct better tables. In addition, each compartment may be able to tolerate more or less supersaturation than others. The final form is a complicated model, but one that allows for the construction of tables suited to a wide variety of diving. A typical dive computer has a 8-12 tissue model, with half times varying from 5 minutes to 400 minutes. The Bühlmann tables

Bühlmann tables

The Bühlmann decompression algorithm is a mathematical model of the way in which inert gases enter and leave the body as the ambient pressure changes. It is used to create Bühlmann tables. These are decompression tables which allow divers to plan the depth and duration for dives and show...

have 16 tissues, with half times varying from 4 minutes to 640 minutes.

Validation of models

It is important that any theory be validated by carefully controlled testing procedures. As testing procedures and equipment become more sophisticated, researchers learn more about the effects of decompression on the body. Initial research focused on producing dives that were free of recognizable symptoms decompression illness (DCI). With the later use of Doppler ultrasound testing, it was realized that bubbles were forming within the body even on dives where no DCI signs or symptoms were encountered. This phenomenon has become known as "silent bubbles". The US Navy tables were based on limits determined by external DCS signs and symptoms. Later researchers were able to improve on this work by adjusting the limitations based on Doppler testing.Since the testing procedures are lengthy and costly, it is common practice for researchers to make initial validations of new models based on experimental results from earlier trials. This has some implications when comparing models.

Residual inert gas

Gas bubble formation has been experimentally shown to significantly inhibit inert gas elimination.The ideal decompression profile creates the greatest possible gradient for inert gas elimination from a tissue without causing bubbles to form.

Repetitive diving, multiples ascents within a single dive, and surface decompression procedures are significant risk factors for DCS.

A considerable amount of inert gas will remain dissolved in the tissues after a diver has surfaced. This residual gas will continue to outgas while the diver remains at the surface. If a repetitive dive is made, the tissues are preloaded with this residual gas which will make them saturate faster.

In repetitive diving, the slower tissues can accumulate gas day after day. This can be a problem for multi-day multi-dive situations. Multiple decompressions per day over multiple days can increase the risk of decompression sickness because of the build up of asymptomatic bubbles, which reduce the rate of off-gassing and are not accounted for in most decompression algorithms. Consequently, some diver training organisations make extra recommendations such as taking "the seventh day off".

John Scott Haldane

Haldane introduced the concept of half times to model the uptake and release of nitrogen into the blood. The half time is the time required for a particular tissue to become half saturated with a gas. He suggested 5 tissue compartments with half times of 5, 10, 20, 40 and 75 minutes.

In this early hypothesis (Haldane 1908) it was predicted that:

If the ascent rate does not allow the inert gas partial pressure in each of the hypothetical tissues to exceed the environmental pressure by more than 2:1 bubbles will not form.

To ensure this a number of decompression stops were incorporated into the ascent schedules.

Basically this meant that one could ascend from 30 m (4 bar) to 10 m (2 bar), or from 10 m (2 bar) to the surface when saturated, without a decompression problem.

This 2:1 ratio was found to be too conservative for fast tissues (short dives) and not conservative enough for slow tissues (long dives).

The ratio also seemed to vary with depth.

The ascent rate and the fastest tissue in the model determine the time and depth of the first stop.

Thereafter the slower tissues determine when it is safe to ascend further.

The ascent rates used on older tables were 18 m/min, but newer tables use 9 m/min.

Workman

Haldane's approach to decompression modeling was used from 1908 to the 1960s with minor modifications, primarily changes to the number of compartments and half times used.

The 1937 US Navy tables were based on research by O. D. Yarbrough and used 3 compartments. The 5 and 10 min compartments were dropped. In the 1950’s the tab;ed were revised and the 5 and 10 minute compartments restored, and a 120 minute compartment added.

In the 1960s Robert D. Workman of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) undertook a review of the basis of the model and subsequent research performed by the US Navy. Tables based on Haldane’s work and subsequent refinements were observed to still be inadequate for longer and deeper dives.

Workman revised Haldane’s model to allow each tissue compartment to tolerate a different amount of supersaturation which varies with depth. He introduced the term "M-value" to indicate the amount of supersaturation each compartment could tolerate at a given depth and added three additional compartments with 160, 200 and 240 minute half times.

Workman presented his findings as an equation which could be used to calculate the results for any depth and stated that a linear projection of M-values would be useful for computer programming.

Bühlmann

A large part of Bühlmann’s research was to determine the longest half time compartments for Nitrogen and Helium, and he increased the number of compartments to 16. He investigated the implications of decompression after diving at altitude and published decompression tables that could be used at a range of altitudes. Bühlmann used a method for decompression calculation similar to that proposed by Workman, which included M-values expressing a linear relationship between maximum inert gas pressure in the tissue compartments and ambient pressure, but based on absolute pressure, which made them more easily adapted for altitude diving.

Bühlmann’s algorithm was used to generate the standard decompression tables for a number of sports diving associations, and are used in several personal decompression computers, sometimes in a modified form.

Torres straits pearl divers

B.A. Hills and D.H. LeMessurier studied the empirical decompression practices of Okinawan pearl divers in the Torres straits and observed that they made deeper stops but reduced the total decompression time compared with the generally used tables of the time. Their analysis strongly suggested that bubble presence limits gas elimination rates, and emphasised the importance of inherent unsaturation of tissues due to metabolic processing of oxygen.

Pyle stops

A "Pyle stop" is an additional brief deep-water stop, which is increasingly used in deep diving

Deep diving

The meaning of the term deep diving is a form of technical diving. It is defined by the level of the diver's diver training, diving equipment, breathing gas, and surface support:...

(named after Richard Pyle, an early advocate of deep stops). Typically, a Pyle stop is 2 minutes long and at the depth where the pressure change halves on an ascent between the bottom and the first conventional decompression stop.

For example, a diver ascends from a maximum depth of 60 metres (196.9 ft), where the ambient pressure is 7 bars (101.5 psi), to a decompression stop at 20 metres (66 ft), where the pressure is 3 bars (43.5 psi). The Pyle stop would take place at the halfway pressure, which is 5 bars (72.5 psi) corresponding to a depth of 40 metres (131.2 ft).

Pyle found that on dives where he stopped periodically to vent the swim-bladders of his fish specimens, he felt better after the dive, and based the deep stop procedure on the depths and duration of these pauses. The hypothesis is that these stops provide an opportunity to eliminate gas while still dissolved, or at least while the bubbles are still small enough to be easily eliminated, and the result is that there will be considerably fewer or smaller venous bubbles to eliminate at the shallower stops as predicted by the thermodynamic model of Hills.

Decompression algorithms

A decompression algorithmAlgorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm is an effective method expressed as a finite list of well-defined instructions for calculating a function. Algorithms are used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning...

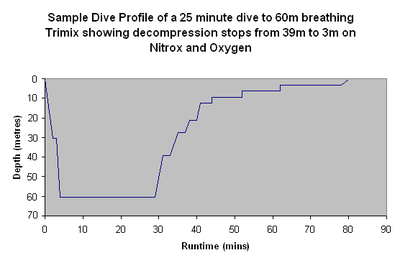

is used to calculate the decompression stops needed for a particular dive profile

Dive profile

A dive profile is a two dimensional graphical representation of a dive showing depth and time.It is useful as an indication of the risks of decompression sickness and oxygen toxicity and also the volume of open-circuit breathing gas needed for a planned dive as these depend in part upon the depth...

to reduce the risk of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

occurring after surfacing at the end of a dive. The algorithm can be used to generate decompression schedules for a particular dive profile, decompression tables for more general use, or be implemented in dive computer

Dive computer

A dive computer or decompression meter is a device used by a scuba diver to measure the time and depth of a dive so that a safe ascent profile can be calculated and displayed so that the diver can avoid decompression sickness.- Purpose :...

software.

Deterministic models

DeterministicDeterminism

Determinism is the general philosophical thesis that states that for everything that happens there are conditions such that, given them, nothing else could happen. There are many versions of this thesis. Each of them rests upon various alleged connections, and interdependencies of things and...

decompression models are a rule based approach to calculating decompression. These models work from the idea that "excessive" supersaturation

Supersaturation

The term supersaturation refers to a solution that contains more of the dissolved material than could be dissolved by the solvent under normal circumstances...

in various tissues

Tissue (biology)

Tissue is a cellular organizational level intermediate between cells and a complete organism. A tissue is an ensemble of cells, not necessarily identical, but from the same origin, that together carry out a specific function. These are called tissues because of their identical functioning...

is "unsafe" (resulting in decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

). They usually contain multiple depth and tissue dependent rules. These rules are revised by qualitative judgment

Judgment

A judgment , in a legal context, is synonymous with the formal decision made by a court following a lawsuit. At the same time the court may also make a range of court orders, such as imposing a sentence upon a guilty defendant in a criminal matter, or providing a remedy for the plaintiff in a civil...

. There is no objective

Objectivity (science)

Objectivity in science is a value that informs how science is practiced and how scientific truths are created. It is the idea that scientists, in attempting to uncover truths about the natural world, must aspire to eliminate personal biases, a priori commitments, emotional involvement, etc...

mathematical way of evaluating the rules or overall risk

Risk

Risk is the potential that a chosen action or activity will lead to a loss . The notion implies that a choice having an influence on the outcome exists . Potential losses themselves may also be called "risks"...

.

Probabilistic models

ProbabilisticProbability

Probability is ordinarily used to describe an attitude of mind towards some proposition of whose truth we arenot certain. The proposition of interest is usually of the form "Will a specific event occur?" The attitude of mind is of the form "How certain are we that the event will occur?" The...

decompression models are designed to calculate the risk

Risk

Risk is the potential that a chosen action or activity will lead to a loss . The notion implies that a choice having an influence on the outcome exists . Potential losses themselves may also be called "risks"...

(or probability) of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

(DCS) occurring on a given decompression profile. These models can vary the decompression stop depths and times to arrive at a final decompression schedule that assumes a specified probability of DCS occurring. The model does this while minimizing the total decompression time. This process can also work in reverse allowing one to calculate the probability of DCS for any decompression schedule.

Bubble models

BubbleBubble

-Physical bubbles:* Liquid bubble, globule of one substance encased in another, usually air in a liquid* Soap bubble, a bubble formed by soapy water * Antibubble, a droplet of liquid surrounded by a thin film of gas-Arts and literature:...

decompression models are a rule based approach to calculating decompression. These models work from the idea that microscopic bubble nuclei always exist in water and tissues that contain water and that by predicting/ controlling the bubble growth, one can avoid decompression sickness.

No decompression limit

The no decompression limit (NDL) or no stop time, is the interval that a diverUnderwater diving

Underwater diving is the practice of going underwater, either with breathing apparatus or by breath-holding .Recreational diving is a popular activity...

may theoretically spend at a given depth without having to perform decompression stops. The NDL helps divers plan dives so that they can stay at a given depth and ascend without stopping while avoiding significant risk of decompression sickness.

The NDL is a theoretical time obtained by calculating inert gas uptake and release in the body, using a model such as the Bühlmann decompression algorithm. Although the science of calculating these limits has been refined over the last century, there is still much that is unknown about how inert gas enter and leave the human body. In addition, every individual's body is unique and may absorb and release inert gases at different rates. For this reason, dive tables typically have a degree of safety built into their recommendations. Divers can and do suffer decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

while remaining inside NDLs.

Each NDL for a range of depths is printed on dive tables in a grid that can be used to plan dives. There are many different tables available as well as software programs and calculators, which will calculate no decompression limits. Most personal decompression computers (dive computers) will indicate a remaining no decompression limit at the current depth during a dive. The displayed interval is continuously revised to take into account changes of depth as well as elapsed time.

Surface interval

The surface interval (SI) or surface interval time (SIT) is the time spent by a diver at surface pressure after a dive during which inert gas which was still present at the end of the dive is further eliminated from the tissues. This continues until the tissues are at equilibrium with the surface pressures. This may take several hours. In the case of the US Navy Air tables, it is considered complete after 12 hours, but other algorithms may require more than 24 hours to assume full equilibrium.Repetitive dives

Any dive which is done while the tissues retain residual inert gas is considered a repetitive dive. This means that the decompression required for the dive is influenced by the divers decompression history. Allowance must be made for inert gas preloading of the tissues which will result in them containing more dissolved gas than would have been the case if the diver has fully equalized before the dive. The diver will need to decompress longer to eliminate this increased gas loading.Residual nitrogen time

For the planned depth of the repetitive dive, a bottom time can be calculated using the relevant algorithm which will provide an equivalent gas loading to the residual gas after the surface interval. This is called "residual nitrogen time" (RNT) when the gas is nitrogen. The RNT is added to the planned "actual bottom time" (ABT) to give an equivalent "total bottom time" (TBT) which is used to derive the required decompression schedule for the planned dive.Equivalent residual times can be derived for other inert gases. These calculations are done automatically in personal diving computers, which is the reason why they should not be shared by divers, and why a diver should not switch computers without a sufficient surface interval (about 24 hours in most cases).

Diving at altitude

The atmospheric pressure decreases with altitude, and this has an effect on the absolute pressure of the diving environment. The most important effect is that the diver must decompress to a lower surface pressure, and this requires longer decompression for the same dive profile.A second effect is that a diver ascending to altitude, will be decompressing en route, and will have residual nitrogen until all tissues have equalized to the local pressures. This means that the diver should consider any dive done before equilibration as a repetitive dive, even if it is the first dive in several days.

The decompression algorithms can be adjusted to compensate for altitude. This was first done by Bühlmann, and is now common on diving computers, where an altitude setting can be selected.

Decompression tables

Dive tables or decompression tables are printed cards or booklets that allow divers to determine for a decompression schedule for a particular dive profile and breathing gas.With dive tables, it is assumed that the dive profile

Dive profile

A dive profile is a two dimensional graphical representation of a dive showing depth and time.It is useful as an indication of the risks of decompression sickness and oxygen toxicity and also the volume of open-circuit breathing gas needed for a planned dive as these depend in part upon the depth...

is a square dive, meaning that the diver descends to maximum depth immediately and stays at the same depth until resurfacing (approximating a rectangular line when drawn in a coordinate system

Coordinate system

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system which uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine the position of a point or other geometric element. The order of the coordinates is significant and they are sometimes identified by their position in an ordered tuple and sometimes by...

where one axis is depth and the other is duration). Some dive tables also assume physical condition or qualifications of the diver, e.g., Navy dive tables should not be used by recreational divers unless they are in similar physical condition and willing to take similar risks to the navy divers the tables were designed for.

Some recreational tables only provide for no-stop dives at sea level sites, but the more complete tables can take into account staged decompression dives and dives performed at altitude

Altitude diving

Altitude diving is scuba diving where the surface is 300 meters or more above sea level . The U.S. Navy tables recommend that no alteration be made for dives at altitudes lower than 91 meters and dives between 91 meters and 300 meters correction is required for dives over 44 meters sea water...

.

Commonly used decompression tables

- US Navy tables;

- Bühlmann tables;

- BSAC 88 tables;

- PADIPadiPadi or PADI may refer to:* Padi, Chennai, India* Padi , a musical group* Paddy field, a type of cultivated land * Professional Association of Diving Instructors, a scuba organization...

tables: the recreational dive planner (RDP) and "the wheel"; - DCIEM tables;

- French Navy 90 tables.

- NAUI Dive tables

Haldane's tables

The original 1908 decompression table theory was based on the assumptions:- uptake and elimination of inert gases take place at the same rate

- these processes are primarily influenced by perfusion and the solubility of the inert gas in that tissue

- gas bubbles do not form in tissues until a critical super-saturation of tissue inert gas was reached.

US Navy tables

Some basic assumptions used in compiling the older versions of the US tables.- Only nitrogen partial pressure would be taken into account when calculating tables.

- The gas tensions in the tissues may be as much as twice the ambient gas pressure, without bubbles being formed.

- Gas uptake rate was assumed to be equal to gas elimination rate; this depends on depth, time, blood flow, gas solubility and gradients.

- Gas exchange is limited by perfusion barriers.

- The body may be represented by a number of theoretical tissues or compartments of varying half life. 6 tissues with half lives of 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 120 minutes were used.

- An ascent rate of 18 m/minute was used

With deeper dives the tables were found to unreliable. The solution was to add more tissues and increase the half life of the slow tissues in the model. These tables were and updated with new research.

Royal Navy tables

Some basic assumptions used in compiling the RN tables- The human body is represented by one tissue with a half life of 87 minutes.

- Gas exchange is limited by perfusion barriers.

- Rate of gas uptake is greater than the rate of elimination. This is because bubbles form in tissue and interfere with the optimal gas elimination, even in symptom free dives.

- Bubbles are produced on virtually every dive.

- The body can cope with a certain number of bubbles (volume) without developing symptoms of decompression sickness (critical volume hypothesis).

The tables work on the principle that bubbles are formed on their way to the first decompression where they are reabsorbed during stage decompression.

Bühlmann tables

The weakness of the critical difference model is that it assumes that the allowable supersatuation will be constant with depth. The models developed by Bühlmann were based on the Workman models, but included factors to account for the concept that the maximum allowable tissue overpressure varied with depth.Recreational Dive Planner

The Recreational Dive Planner (or RDP) is a decompression table in which no-stop time underwater is calculated. The RDP was developed by DSAT

Diving Science and Technology

Diving Science and Technology is a corporate affiliate of the Professional Association of Diving Instructors and the developer of the Recreational Dive Planner. DSAT has held scientific workshops for diver safety and education....

and was the first dive table developed exclusively for recreational, no stop diving. There are four types of RDPs: the original table version first introduced in 1988, The Wheel version, the original electronic version or eRDP introduced in 2005 and the latest electronic multi-level version or eRDPML introduced in 2008.

The low price and convenience of many modern dive computer

Dive computer

A dive computer or decompression meter is a device used by a scuba diver to measure the time and depth of a dive so that a safe ascent profile can be calculated and displayed so that the diver can avoid decompression sickness.- Purpose :...

s mean that many recreational divers

Recreational diving

Recreational diving or sport diving is a type of diving that uses SCUBA equipment for the purpose of leisure and enjoyment. In some diving circles, the term "recreational diving" is used in contradistinction to "technical diving", a more demanding aspect of the sport which requires greater levels...

only use tables such as the RDP for a short time during training before moving on to use a diving computer.

Decompression software

Decompression software such as Departure, DecoPlanner, Ultimate Planner, Z-Planner, V-Planner and GAP are available, which simulate the decompression requirements of different dive profileDive profile

A dive profile is a two dimensional graphical representation of a dive showing depth and time.It is useful as an indication of the risks of decompression sickness and oxygen toxicity and also the volume of open-circuit breathing gas needed for a planned dive as these depend in part upon the depth...

s with different gas mixtures using decompression algorithms.

Bespoke tables or schedules generated by decompression software represent a diver's specific dive plan and breathing gas

Breathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

mixtures. It is usual to generate a schedule for the planned profile and for the most likely contingency profiles.

Personal decompression computers

The personal dive computer is a small computer with pressure sensor which is mounted in a waterproof and pressure resistant housing and has been programmed to model the inert gas loading of the diver's tissues in real time during a dive. Most are wrist mounted, but a few are mounted in a console with the submersible pressure gauge and possibly other instruments. A display allows the diver to see critical data during the dive, including the maximum and current depth, duration of the dive, and decompression data. Other data such as water temperature and cylinder pressure are also sometimes displayed. The dive computer has the advantages of monitoring the actual dive, as opposed to the planned dive, and does not work on a "square profile" - it dynamically calculates the real profile of pressure exposure in real time, and keeps track of residual gas loading for each tissue used in the algorithm.Bottom time

Bottom time is the time spent at depth before starting the ascent.Bottom time used for decompression planning may be defined differently depending on the tables or algorithm used. It may include descent time, but not in all cases. It is important to check what bottom time is defined for the tables before they are used.

Continuous decompression

Continuous decompression is decompression without stops. Instead of a fairly rapid ascent rate to the first stop, followed by a period at static depth during the stop, the ascent is slower, but without officially stopping. In theory this is the optimum decompression profile. In practice this is very difficult to do manually, and it may be necessary to stop the ascent occasionally to get back on schedule, but these stops are not part of the schedule, they are corrections. To further complicate the practice, the ascent rate may vary with the depth, and is typically faster at greater depth and reduces as the depth gets shallower. In practice a continuous decompression profile may be approximated by ascent in steps as small as the chamber pressure gauge will resolve, and timed to followthe theoretical profile as closely as conveniently practicable.For example, continuous decompression is used in USN treatment table 7. This table uses an ascent rate of 3 fsw per hour from 60 fsw to 40 fsw, followed by 2 fsw per hour from 40 fsw to 20 fsw and 1 fsw per hour from 20 fsw to 4 fsw.

No decompression dives, ascent rate and safety stops

A "no stop" dive is a dive that needs no decompression stops during the ascent and relies on a controlled ascent rate for the elimination of excess inert gases. In effect, the diver is doing continuous decompression during the ascent.Dive computers

Dive computerDive computer

A dive computer or decompression meter is a device used by a scuba diver to measure the time and depth of a dive so that a safe ascent profile can be calculated and displayed so that the diver can avoid decompression sickness.- Purpose :...

s are designed to be worn by a diver during a dive. These computers contain, at a minimum, a pressure sensor

Pressure sensor

A pressure sensor measures pressure, typically of gases or liquids. Pressure is an expression of the force required to stop a fluid from expanding, and is usually stated in terms of force per unit area. A pressure sensor usually acts as a transducer; it generates a signal as a function of the...

and an electronic timer

Timer

A timer is a specialized type of clock. A timer can be used to control the sequence of an event or process. Whereas a stopwatch counts upwards from zero for measuring elapsed time, a timer counts down from a specified time interval, like an hourglass.Timers can be mechanical, electromechanical,...

. They use a decompression algorithm

Algorithm

In mathematics and computer science, an algorithm is an effective method expressed as a finite list of well-defined instructions for calculating a function. Algorithms are used for calculation, data processing, and automated reasoning...

to calculate the inert gas loading on one or more tissue compartments and display the remaining no decompression limit calculated in real time for the diver throughout the dive. When planning a dive using dive tables, divers assume that the entire dive is spent at whatever the maximum depth will be. Using a computer, the diver is credited for the time they spend at lesser depths during a multi-level dive.

Dive computers also provide a measure of safety for divers that accidentally dive a different profile to that originally planned. If the diver exceeds a no decompression limit, decompression additional to the ascent rate will be necessary. Many dive computers will provide required decompression information in the event that the no decompression limits are exceeded.

Ascent rate

In addition to stops, the diver must not exceed a safe ascent rate during the whole of the ascent from depth. Normally the time to ascend from the shallowest stop to the surface will take at least 1 minute. Typically with tables, the maximum ascent rate is 10 metres (33 ft) per minute when deeper than 6 metres (20 ft). Some dive computers have variable maximum ascent rates, depending on depth.Safety stop

As a precaution against any unnoticed dive computer malfunction, diver error or physiologicalPhysiology

Physiology is the science of the function of living systems. This includes how organisms, organ systems, organs, cells, and bio-molecules carry out the chemical or physical functions that exist in a living system. The highest honor awarded in physiology is the Nobel Prize in Physiology or...

predisposition to decompression sickness, many divers do an extra "safety stop" in addition to those ordered by their dive computer or tables. A safety stop is typically 1 to 5 minutes at 3 to 6 m (9.8 to 19.7 ft). They are usually done during no-stop dives and may be added to the obligatory decompression on staged dives.

Staged decompression and decompression stops

A decompression stop is a period of time a diverScuba diving

Scuba diving is a form of underwater diving in which a diver uses a scuba set to breathe underwater....

must spend at a constant depth in shallow water at the end of a dive to safely eliminate absorbed inert gas

Inert gas

An inert gas is a non-reactive gas used during chemical synthesis, chemical analysis, or preservation of reactive materials. Inert gases are selected for specific settings for which they are functionally inert since the cost of the gas and the cost of purifying the gas are usually a consideration...

es from the diver's body to avoid decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

. The practice of making decompression stops is called staged decompression, as opposed to continuous decompression.

A decompression schedule is a series of increasingly shallower decompression stops—often for increasing amounts of time—that a diver uses to outgas inert gases from their body during ascent to the surface to reduce the risk of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

. In a decompression dive, the decompression phase may make up a large part of the time spent underwater (in many cases it is longer than the actual time spent at depth).

The depth and duration of each stop is dependent on many factors, primarily the profile of depth and time of the dive, but also the breathing gas

Breathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

mix, the interval since the previous dive and the altitude of the dive site. The diver obtains the depth and duration of each stop from a dive computer

Dive computer

A dive computer or decompression meter is a device used by a scuba diver to measure the time and depth of a dive so that a safe ascent profile can be calculated and displayed so that the diver can avoid decompression sickness.- Purpose :...

, decompression tables or dive planning computer software. A deco diver will typically prepare more than one decompression schedule to plan for contingencies such as going deeper than planned or spending longer at depth than planned.

Doing a decompression stop

Dive computer

A dive computer or decompression meter is a device used by a scuba diver to measure the time and depth of a dive so that a safe ascent profile can be calculated and displayed so that the diver can avoid decompression sickness.- Purpose :...

s to find, for his planned dive profile

Dive profile

A dive profile is a two dimensional graphical representation of a dive showing depth and time.It is useful as an indication of the risks of decompression sickness and oxygen toxicity and also the volume of open-circuit breathing gas needed for a planned dive as these depend in part upon the depth...

and breathing gas

Breathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

, if decompression stops are needed, and if so, the depths and durations of the stops.

Shorter and shallower decompression dives may only need one single short shallow decompression stop, for example 5 minutes at 3 metres (10 ft). Longer and deeper dives often need a series of decompression stops, each stop being longer but shallower than the previous stop.

After the bottom sector of the dive, the ascent is made at the recommended rate until the diver reaches the depth of the first stop. The diver then maintains the specified stop depth for the specified period, before ascending to the next stop depth at the recommended rate, and follows the same procedure again. This is repeated until all required decompression has been completed and the diver reaches the surface.

Once on the surface the diver will continue to eliminate inert gas until the concentrations have returned to normal surface saturation, which can take several hours, and is considered by some tables to be effectively compete after 12 hours, and by others to take up to, or even more than 24 hours.

Missed stops

A diver missing a required decompression stop risks developing decompression sickness. The risk is related to the depth and duration of the missed stops. The usual causes for missing stops are: not having enough breathing gasBreathing gas

Breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration.Air is the most common and only natural breathing gas...

to complete the stops, or accidentally losing control of buoyancy. An aim of most basic diver training

Diver training

Diver training is the process of developing skills and building experience in the use of diving equipment and techniques so that the diver is able to dive safely and have fun....

is to prevent these two faults. There are less predictable causes of missing decompression stops. Diving suit

Diving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit typically also incorporates an air-supply .-History:...

failure in cold water forces the diver to choose between hypothermia

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is a condition in which core temperature drops below the required temperature for normal metabolism and body functions which is defined as . Body temperature is usually maintained near a constant level of through biologic homeostasis or thermoregulation...

and decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

. Diver injury or marine animal attack may also limit the duration of stops the diver is willing to carry out.

Technical diving

Technical diving

Technical diving is a form of scuba diving that exceeds the scope of recreational diving...

education organizations define special procedures to be done if decompression stops are missed. These procedures may need repeating one or several stops.

A procedure for dealing with omitted decompression stops is described in the US Navy Diving Manual In principle the procedure allows a diver who is not yet presenting symptoms of decompression sickness, to go back down and complete the omitted decompression, with some extra added to deal with the bubbles which are assumed to have formed during the period where the decompression ceiling was violated. Divers who become symptomatic before they can be returned to depth are treated for decompression sickness, and do not attempt the omitted decompression procedure as the risk is considered unacceptable under normal operational circumstances.

Accelerated decompression

Decompression can be accelerated by the use of breathing gases during ascent with lowered inert gas fractions (as a result of increased oxygen fraction). This will result in a greater diffusion gradient for a given ambient pressure, and consequently accelerated decompression for a relatively low risk of bubble formation. Nitrox mixtures and oxygen are the most commonly used gases for this purpose, but oxygen rich Trimix blends can also be used after a Trimix dive, and may reduce risk of counterdiffusion complications.Ratio decompression

Ratio decompression (usually referred to in abbreviated form as ratio deco) is a technique for calculating decompression schedules for scuba divers engaged in deep diving without using dive tables, decompression software or a dive computer. It is generally taught as part of the "DIR" philosophy of diving promoted by organisations such Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) and Unified Team Diving (UTD) at the advanced technical diving level. It is designed for decompression diving executed deeper than standard recreational diving depth limits using trimix as a "bottom mix" breathing gas.It is largely an empirical procedure, and has a reasonable safety record within the scope of its intended application. Advantages are reduced overall decompression time and easy estimation of decompression by the use of a simple rule-based procedure which can be done underwater by the diver. It requires the use of specific gas mixtures for given depth ranges.

Surface decompression

Surface decompression is a procedure in which some or all of the staged decompression obligation is done in a decompression chamber instead of in the water. This reduces the time that the diver spends in the water, exposed to environmental hazards such as cold water or currents, which will enhance diver safety. The decompression in the chamber is more controlled, in a more comfortable environment, and oxygen can be used at greater partial pressure as there in no risk of drowning and a lower risk of oxygen toxicity convulsions. A further operational advantage is that once the divers are in the chamber, new divers can be supplied from the diving panel, and the operations can continue with less delay.A typical surface decompression procedure is described in the US Navy Diving Manual. If there is no in-water 40ft stop required the diver is surfaced directly. All required decompression up to and including the 40 ft (12 m) stop is completed in-water. The diver is then surfaced and pressurised in a chamber to 50 fsw within 5 minutes of leaving 40 ft depth in the water. If this "surface interval" from 40 ft in the water to 50 fsw in the chamber exceeds 5 minutes, a penalty is incurred, as this indicates a higher risk of DCS symptoms developing, so longer decompression is required.

In the case where the diver is successfully recompressed within the nominal interval, he will be decompressed according to the schedule in the air decompression tables for surface decompression, preferably on oxygen, which is used from 40 fsw (12 msw), a partial pressure of 2.2 bar. Stops are also done at 30 fsw and 20 fsw, for times according to the schedule. Air breaks of 5 minutes are taken at the end of each 30 minutes of oxygen breathing.

Surface decompression procedures have been described as "semi-controlled accidents”.

Dry bell decompression

"Dry", or "Closed" diving bells are pressure vessels for human occupation which can be deployed from the surface to transport divers to the underwater workplace at pressures greater than ambient. They are equalized to ambient pressure at the depth where the divers will get out and back in after the dive, and are then re-sealed for transport back to the surface, which also generally takes place with controlled internal pressure greater than ambient. During and/or after the recovery from depth, the divers may be decompressed in the same way as if they were in a decompression chamber, so in effect, the dry bell is a mobile decompression chamber. Another option, used in saturation diving, is to decompress to storage pressure (pressure in the habitat part of the saturation spread) and then transfer the divers to the saturation habitat under pressure (transfer under pressure - TUP), where they will stay until the next shift, or until decompressed at the end of the saturation period.Saturation decompression

Once all the tissue compartments have reached saturation for a given pressure and breathing mixture, continued exposure will not increase the gas loading of the tissues. From this point onwards the required decompression remains the same. If divers work and live at pressure for a long period, and are decompressed only at the end of the period, the risks associated with decompression are limited to this single exposure. This principle has led to the practice of saturation divingSaturation diving

Saturation diving is a diving technique that allows divers to reduce the risk of decompression sickness when they work at great depth for long periods of time....

, and as there is only one decompression, and it is done in the relative safety and comfort of a saturation habitat, the decompression is done on a very conservative profile, minimising the risk of bubble formation, growth and the consequent injury to tissues. A consequence of these procedures is that saturation divers are more likely to suffer decompression sickness symptoms in the slowest tissues, whereas bounce divers are more likely to develop bubbles in faster tissues.

Therapeutic decompression

Therapeutic decompression is a procedure for treating decompression sickness by recompressing the diver, thus reducing bubble size, and allowing the gas bubbles to re-dissolve, then decompressing slowly enough to avoid further formation or growth of bubbles, or eliminating the inert gases by breathing oxygen under pressure.Therapeutic decompression on air

Historically, therapeutic decompression was done by recompressing the diver to the depth of relief of pain, or a bit deeper, maintaining that pressure for a while, so that bubbles could be re-dissolved, and performing a slow decompression back to the surface pressure. Later air tables were standardised to specific depths, followed by slow decompression. This procedure has been superseded almost entirely by hyperbaric oxygen treatment.Recompression on atmospheric air was shown to be an effective treatment for minor DCS symptoms by Keays in 1909.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Evidence of the effectiveness of recompression therapy utilizing oxygen was first shown by Yarbrough and BehnkeAlbert R. Behnke

Captain Albert Richard Behnke Jr. USN was an American physician, who was principally responsible for developing the U.S. Naval Medical Research Institute...

, and has since become the standard of care for treatment of DCS.

A typical hyperbaric oxygen treatment schedule is the US Navy Table 6, which provides for a standard treatment of 3 to 5 periods of 20 minutes of oxygen breathing at 60 fsw (18msw) followed by 2 to 4 periods of 60 minutes at 30 fsw (9 msw) before surfacing. Air breaks are taken between oxygen breathing to reduce the risk of oxygen toxicity.

In water recompression

If a chamber is not available for recompression within a reasonable period, a riskier alternative is in-water recompressionIn-water recompression

In-water recompression or underwater oxygen treatment is the emergency treatment of decompression sickness of sending the diver back underwater to allow the gas bubbles in the tissues, which are causing the symptoms, to resolve...

at the dive site.

In-water recompression (IWR) is the emergency treatment of decompression sickness (DCS) by sending the diver back underwater to allow the gas bubbles in the tissues, which are causing the symptoms, to resolve. It is a risky procedure that should only be used when it is not practicable to travel to the nearest recompression chamber in time to save the victim's life.

The procedure is high risk as a diver suffering from DCS may become paralysed, unconscious or stop breathing whilst under water. Any one of these events may result in the diver drowning or further injury to the diver during a subsequent rescue to the surface. These risks can be mitigated to some extent by using a helmet or full-face mask with voice communications on the diver, and suspending the diver from the surface so that depth is positively controlled, and by having an in-water standby diver attend the diver undergoing the treatment at all times.

The principle behind in water recompression treatment is the same as that behind the treatment of DCS in a recompression chamber

Although in-water recompression is regarded as risky, and to be avoided, there is increasing evidence that technical divers who surface and demonstrate mild DCS symptoms may often get back into the water and breathe pure oxygen at a depth 20 feet/6 meters for a period of time to seek to alleviate the symptoms. This trend is noted in paragraph 3.6.5 of DAN

Divers Alert Network

The Divers Alert Network is a non-profit 501 organization devoted to assisting divers in need. The Research department conducts significant medical research on recreational scuba diving safety...

's 2008 accident report. The report also notes that whilst the reported incidents showed very little success, "[w]e must recognize that these calls were mostly because the attempted IWR failed. In case the IWR were successful, [the] diver would not have called to report the event. Thus we do not know how often IWR may have been used successfully."

Historically, in-water recompression was the usual method of treating decompression sickness in remote areas. Procedures were often informal and based on operator experience, and used air as the breathing gas as it was all that was available. The divers generally used standard diving gear, which was relatively safe for this procedure, as the diver was at low risk of drowning if he lost consciousness.

Decompression equipment