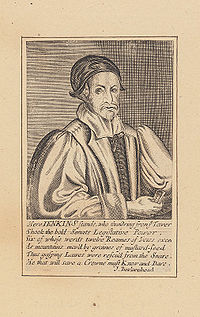

David Jenkins (Royalist)

Encyclopedia

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

judge and Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

during the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

.

Jenkins was born at Pendeulwyn (English: Pendoylan

Pendoylan

Pendoylan is a rural village in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, which has won many awards in Best Kept Village competitions and contains 27 entries in the Council's County Treasures database, 13 of which are listed buildings.- Location :...

), Glamorgan

Glamorgan

Glamorgan or Glamorganshire is one of the thirteen historic counties and a former administrative county of Wales. It was originally an early medieval kingdom of varying boundaries known as Glywysing until taken over by the Normans as a lordship. Glamorgan is latterly represented by the three...

, son of a well-established gentry family. He was educated at St Edmund Hall, Oxford

St Edmund Hall, Oxford

St Edmund Hall is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Better known within the University by its nickname, "Teddy Hall", the college has a claim to being "the oldest academical society for the education of undergraduates in any university"...

, admitted to Gray's Inn

Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

on 5 November 1602 and called to the bar in 1609. In March 1643 he was appointed, against his will, as pucine judge of the Carmarthen

Carmarthen

Carmarthen is a community in, and the county town of, Carmarthenshire, Wales. It is sited on the River Towy north of its mouth at Carmarthen Bay. In 2001, the population was 14,648....

circuit of the court of great sessions. He was a strong supporter of the royalist cause in the civil war, and later that year was involved in raising money for the siege of Gloucester

Gloucester

Gloucester is a city, district and county town of Gloucestershire in the South West region of England. Gloucester lies close to the Welsh border, and on the River Severn, approximately north-east of Bristol, and south-southwest of Birmingham....

and he also indicted several prominent parliamentarians for high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

. Jenkins was captured by the parliamentarians

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

in December 1645 in Hereford

Hereford

Hereford is a cathedral city, civil parish and county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, southwest of Worcester, and northwest of Gloucester...

and imprisoned in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

, Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

and latterly in Wallingford

Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire , adjacent to the River Thames...

and Windsor

Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a medieval castle and royal residence in Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, notable for its long association with the British royal family and its architecture. The original castle was built after the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror. Since the time of Henry I it...

Castles. Whilst in prison in the 1640s, Jenkins wrote a number of political tracts which were collectively published in 1648 as: The Works of the Eminent and Learned Judge Jenkins upon divers Statutes concerning the King's Prerogative and the Liberty of the Subject.

Jenkins was brought before parliament

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

in April 1647, but argued that it had no power to try him in the absence of the king. His arguments were expounded in his scholarly work, Lex Terrae which cited important authorities. The nub of his case, against the legitimacy of parliament in appointing justices and passing laws, was that such acts could only be performed with the explicit authority of the king and that the claim that the king was 'virtually' present in proceedings of the two Houses of Parliament

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, is the meeting place of the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom—the House of Lords and the House of Commons...

was false.

On 22 February 1648, Jenkins was brought to the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

to face charges including the writing of treasonous pamphlets. He refused to kneel at the bar of the house and was fined £1000 for contempt. In 1650 Jenkins was amongst other prisoners that the Rump Parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

considered executing. He said that if he was to go to the scaffold he would be "hanged with the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

under one arm and Magna Charta under the other".

Jenkins was eventually released in 1657 prior to the restoration of the monarchy

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

. His estate at Hensol

Hensol Castle

Hensol Castle is a castellated mansion in the gothic architecture style dating from the late 17th century or early 18th century. It is located north of Clawdd Coch and Tredodridge in the parish of Pendoylan in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales...

had been sequestered

Sequestration (law)

Sequestration is the act of removing, separating, or seizing anything from the possession of its owner under process of law for the benefit of creditors or the state.-Etymology:...

in 1652, but he regained it (estimated to be worth £1500 p.a.) and lived there becoming patron of the bards. He died in 1663 and was buried at Cowbridge

Cowbridge

Cowbridge is a market town in the Vale of Glamorgan in Wales, approximately west of Cardiff. Cowbridge is twinned with Clisson in the Loire-Atlantique department in northwestern France.-Roman times:...

. The obituary

Obituary

An obituary is a news article that reports the recent death of a person, typically along with an account of the person's life and information about the upcoming funeral. In large cities and larger newspapers, obituaries are written only for people considered significant...

for Jenkins is apparently the first of its kind in the English-speaking world, published in The Newes on 17 December 1663 by Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

's Surveyor of the Press, Roger L'Estrange

Roger L'Estrange

Sir Roger L'Estrange was an English pamphleteer and author, and staunch defender of royalist claims. L'Estrange was involved in political controversy throughout his life...

.http://www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,3604,1234329,00.html Part of it read:

"... that Eminent, Loyall, and renowned Patriot, Judge Jenkins, Departed this Life at his House in Cowbridge, [at] 81..in perfect Sence and Memory. He dyed, as he lived, preaching with his last Breath to his Relations, and those who were about him, Loyalty to his Majesty, and Obedience to the Lawes of the Land. In fine, he has carried with him all the comforts of a Quiet Conscience, and left behind him an unspotted Fame..."