Siderophore

Encyclopedia

Siderophores are small, high-affinity iron

chelating

compounds secreted by grasses and microorganism

s such as bacteria and fungi. Siderophores are amongst the strongest soluble Fe3+ binding agents known.

of the Fe3+ ion. This is the predominant state of iron in aqueous, non-acidic, oxygenated environments. It accumulates in common mineral phases such as iron oxides and hydroxides (the minerals that are responsible for red and yellow soil colours) hence cannot be readily utilized by organisms. Microbes release siderophores to scavenge iron from these mineral phases by formation of soluble Fe3+

complex

es that can be taken up by active transport

mechanisms. Many siderophores are nonribosomal peptide

s, although several are biosynthesised independently.

Siderophores are also important for some pathogenic bacteria for their acquisition of iron. In mammalian hosts, iron is tightly bound to proteins such as hemoglobin

, transferrin

, lactoferrin

and ferritin

. The strict homeostasis of iron leads to a free concentration of about 10−24 mol L−1, hence there are great evolutionary pressures put on pathogenic bacteria to obtain this metal. For example, the anthrax

pathogen Bacillus anthracis releases two siderophores, bacillibactin and petrobactin, to scavenge ferric iron from iron proteins. While bacillibactin has been shown to bind to the immune system protein siderocalin

, petrobactin is assumed to evade the immune system and has been shown to be important for virulence in mice.

Siderophores are amongst the strongest binders to Fe3+ known, with enterobactin

being one of the strongest of these. Because of this property, they have attracted interest from medical science in metal chelation therapy

, with the siderophore desferrioxamine B

gaining widespread use in treatments for iron poisoning

and thalassemia

.

Besides siderophores, some pathogenic bacteria produce hemophores (heme

binding scavenging proteins) or have receptors that bind directly to iron/heme proteins. In eukaryotes, other strategies to enhance iron solubility and uptake are the acid

ification of the surrounding (e.g. used by plant roots) or the extracellular

reduction of Fe3+

into the more soluble Fe2+

ions.

s per molecule, forming a hexadentate complex and causing a smaller entropic change than that caused by chelating a single ferric ion with separate ligands. For a representative collection of siderophores see Studies and Syntheses of Siderophores, Microbial Iron Chelators, and Analogs as Potential Drug Delivery Agents by Marvin J. Miller.

Fe3+ is a hard Lewis acid

, preferring hard Lewis bases such as anionic or neutral oxygen to coordinate with. Microbes usually release the iron from the siderophore by reduction to Fe2+ which has little affinity to these ligands.

Siderophores are usually classified by the ligands used to chelate the ferric iron. The major groups of siderophores include the catecholates (phenolates), hydroxamate

s and carboxylates (e.g. derivatives of citric acid

). Citric acid can also act as a siderophore. The wide variety of siderophores may be due to evolutionary pressures placed on microbes to produce structurally different siderophores which cannot be transported by other microbes' specific active transport systems, or in the case of pathogens deactivated by the host organism.

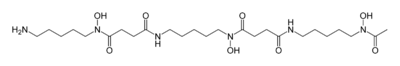

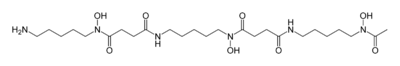

Hydroxamate siderophores

Hydroxamate siderophores

Catecholate siderophores

Mixed ligands

Some poaceae

(grasses) including wheat

and barley

produce a class of siderophores called phytosiderophores or mugineic acids.

) it is DtxR (diphtheria toxin repressor), so-called as the production of the dangerous diphtheria toxin

by Corynebacterium diphtheriae

is also regulated by this system.

This is followed by excretion of the siderophore into the extracellular environment, where the siderophore acts to sequester and solubilize the iron. Siderophores are then recognized by cell specific receptors on the outer membrane of the cell. In fungi and other eukaryotes, the Fe-siderophore complex may be extracellularly reduced to Fe2+, whilst in many cases the whole Fe-siderophore complex is actively transported across the cell membrane. In gram-negative bacteria, these are transported into the periplasm via TonB-dependent receptors

, and is transferred into the cytoplasm by ABC transporters.

Once in the cytoplasm of the cell, the Fe3+-siderophore complex is usually reduced to Fe2+ to release the iron, especially in the case of "weaker" siderophore ligands such as hydroxamates and carboxylates. Siderophore decomposition or other biological mechanisms can also release iron., especially in the case of catecholates such as ferric-enterobactin, whose reduction potential is too low for reducing agents such as flavin adenine dinucleotide, hence enzymatic degradation is needed to release the iron.

Siderophores are useful as drugs in facilitating iron mobilization in humans, especially in the treatment of iron diseases, due to their high affinity for iron. One potentially powerful application is to use the iron transport abilities of siderophores to carry drugs into cells by preparation of conjugates between siderophores and antimicrobial agents. Because microbes recognize and utilize only certain siderophores, such conjugates are anticipated to have selective antimicrobial activity.

Microbial iron transport (siderophore)-mediated drug delivery makes use of the recognition of siderophores as iron delivery agents in order to have the microbe assimilate siderophore conjugates with attached drugs. These drugs are lethal to the microbe and cause the microbe to apoptosis

e when it assimilates the siderophore conjugate. Through the addition of the iron-binding functional groups of siderophores into antibiotics, their potency has been greatly increased. This is due to the siderophore-mediated iron uptake system of the bacteria.

(grasses) including agriculturally important species such as barley

and wheat

are able to efficiently sequester iron by releasing phytosiderophores via their root

into the surrounding soil

rhizosphere

. Chemical compounds produced by microorganisms in the rhizosphere can also increase the availability and uptake of iron. Plants such as oats are able to assimilate iron via these microbial siderophores. It has been demonstrated that plants are able to use the hydroxamate-type siderophores ferrichrome, rodotorulic acid and ferrioxamine B; the catechol-type siderophores, agrobactin; and the mixed ligand catechol-hydroxamate-hydroxy acid siderophores biosynthesized by saprophytic root-colonizing bacteria. All of these compounds are produced by rhizospheric bacterial strains, which have simple nutritional requirements, and are found in nature in soils, foliage, fresh water, sediments, and seawater.

Fluorescent pseudomonads have been recognized as biocontrol agents against certain soil-borne plant pathogens. They produce yellow-green pigments (pyoverdines) which fluoresce under UV light and function as siderophores. They deprive pathogens of the iron required for their growth and pathogenesis.

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

chelating

Chelation

Chelation is the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between apolydentate ligand and a single central atom....

compounds secreted by grasses and microorganism

Microorganism

A microorganism or microbe is a microscopic organism that comprises either a single cell , cell clusters, or no cell at all...

s such as bacteria and fungi. Siderophores are amongst the strongest soluble Fe3+ binding agents known.

The scarcity of soluble iron

Iron is essential for almost all life, essential for processes such as respiration and DNA synthesis. Despite being one of the most abundant elements in the Earth’s crust, the bioavailability of iron in many environments such as the soil or sea is limited by the very low solubilitySolubility

Solubility is the property of a solid, liquid, or gaseous chemical substance called solute to dissolve in a solid, liquid, or gaseous solvent to form a homogeneous solution of the solute in the solvent. The solubility of a substance fundamentally depends on the used solvent as well as on...

of the Fe3+ ion. This is the predominant state of iron in aqueous, non-acidic, oxygenated environments. It accumulates in common mineral phases such as iron oxides and hydroxides (the minerals that are responsible for red and yellow soil colours) hence cannot be readily utilized by organisms. Microbes release siderophores to scavenge iron from these mineral phases by formation of soluble Fe3+

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

complex

Complex (chemistry)

In chemistry, a coordination complex or metal complex, is an atom or ion , bonded to a surrounding array of molecules or anions, that are in turn known as ligands or complexing agents...

es that can be taken up by active transport

Active transport

Active transport is the movement of a substance against its concentration gradient . In all cells, this is usually concerned with accumulating high concentrations of molecules that the cell needs, such as ions, glucose, and amino acids. If the process uses chemical energy, such as from adenosine...

mechanisms. Many siderophores are nonribosomal peptide

Nonribosomal peptide

Nonribosomal peptides are a class of peptide secondary metabolites, usually produced by microorganisms like bacteria and fungi. Nonribosomal peptides are also found in higher organisms, such as nudibranchs, but are thought to be made by bacteria inside these organisms...

s, although several are biosynthesised independently.

Siderophores are also important for some pathogenic bacteria for their acquisition of iron. In mammalian hosts, iron is tightly bound to proteins such as hemoglobin

Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein in the red blood cells of all vertebrates, with the exception of the fish family Channichthyidae, as well as the tissues of some invertebrates...

, transferrin

Transferrin

Transferrins are iron-binding blood plasma glycoproteins that control the level of free iron in biological fluids. In humans, it is encoded by the TF gene.Transferrin is a glycoprotein that binds iron very tightly but reversibly...

, lactoferrin

Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin , also known as lactotransferrin , is a multifunctional protein of the transferrin family. Lactoferrin is a globular glycoprotein with a molecular mass of about 80 kDa that is widely represented in various secretory fluids, such as milk, saliva, tears, and nasal secretions...

and ferritin

Ferritin

Ferritin is a ubiquitous intracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The amount of ferritin stored reflects the amount of iron stored. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including bacteria, algae and higher plants, and animals...

. The strict homeostasis of iron leads to a free concentration of about 10−24 mol L−1, hence there are great evolutionary pressures put on pathogenic bacteria to obtain this metal. For example, the anthrax

Anthrax

Anthrax is an acute disease caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Most forms of the disease are lethal, and it affects both humans and other animals...

pathogen Bacillus anthracis releases two siderophores, bacillibactin and petrobactin, to scavenge ferric iron from iron proteins. While bacillibactin has been shown to bind to the immune system protein siderocalin

Siderocalin

Siderocalin is a protein that is produced by the body in response to bacterial infection. During an infection, bacteria produce iron-chelators called siderophores, which are used for 'stealing' iron from the host. E...

, petrobactin is assumed to evade the immune system and has been shown to be important for virulence in mice.

Siderophores are amongst the strongest binders to Fe3+ known, with enterobactin

Enterobactin

Enterobactin is a high affinity siderophore that acquires iron for microbial systems. It is primarily found in Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium....

being one of the strongest of these. Because of this property, they have attracted interest from medical science in metal chelation therapy

Chelation therapy

Chelation therapy is the administration of chelating agents to remove heavy metals from the body. For the most common forms of heavy metal intoxication—those involving lead, arsenic or mercury—the standard of care in the United States dictates the use of dimercaptosuccinic acid...

, with the siderophore desferrioxamine B

Deferoxamine

Deferoxamine is a bacterial siderophore produced by the actinobacteria Streptomyces pilosus. It has medical applications as a chelating agent used to remove excess iron from the body...

gaining widespread use in treatments for iron poisoning

Iron poisoning

Iron poisoning is an iron overload caused by a large excess of iron intake and usually refers to an acute overload rather than a gradual one. The terms has been primarily associated with young children who consumed large quantities of iron supplement pills, which resemble sweets and are widely...

and thalassemia

Thalassemia

Thalassemia is an inherited autosomal recessive blood disease that originated in the Mediterranean region. In thalassemia the genetic defect, which could be either mutation or deletion, results in reduced rate of synthesis or no synthesis of one of the globin chains that make up hemoglobin...

.

Besides siderophores, some pathogenic bacteria produce hemophores (heme

Heme

A heme or haem is a prosthetic group that consists of an iron atom contained in the center of a large heterocyclic organic ring called a porphyrin. Not all porphyrins contain iron, but a substantial fraction of porphyrin-containing metalloproteins have heme as their prosthetic group; these are...

binding scavenging proteins) or have receptors that bind directly to iron/heme proteins. In eukaryotes, other strategies to enhance iron solubility and uptake are the acid

Acid

An acid is a substance which reacts with a base. Commonly, acids can be identified as tasting sour, reacting with metals such as calcium, and bases like sodium carbonate. Aqueous acids have a pH of less than 7, where an acid of lower pH is typically stronger, and turn blue litmus paper red...

ification of the surrounding (e.g. used by plant roots) or the extracellular

Extracellular

In cell biology, molecular biology and related fields, the word extracellular means "outside the cell". This space is usually taken to be outside the plasma membranes, and occupied by fluid...

reduction of Fe3+

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

into the more soluble Fe2+

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

ions.

Structure and Identification

Siderophores usually form a stable, hexadentate, octahedral complex with Fe3+ preferentially compared to other naturally occurring abundant metal ions, although if there are less than six donor atoms water can also coordinate. The most effective siderophores are those that have three bidentate ligandLigand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding between metal and ligand generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electron pairs. The nature of metal-ligand bonding can range from...

s per molecule, forming a hexadentate complex and causing a smaller entropic change than that caused by chelating a single ferric ion with separate ligands. For a representative collection of siderophores see Studies and Syntheses of Siderophores, Microbial Iron Chelators, and Analogs as Potential Drug Delivery Agents by Marvin J. Miller.

Fe3+ is a hard Lewis acid

Lewis acid

]The term Lewis acid refers to a definition of acid published by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1923, specifically: An acid substance is one which can employ a lone pair from another molecule in completing the stable group of one of its own atoms. Thus, H+ is a Lewis acid, since it can accept a lone pair,...

, preferring hard Lewis bases such as anionic or neutral oxygen to coordinate with. Microbes usually release the iron from the siderophore by reduction to Fe2+ which has little affinity to these ligands.

Siderophores are usually classified by the ligands used to chelate the ferric iron. The major groups of siderophores include the catecholates (phenolates), hydroxamate

Hydroxamic acid

A hydroxamic acid is a class of chemical compounds sharing the same functional group in which an hydroxylamine is inserted into a carboxylic acid. Its general structure is R-CO-NH-OH, with an R as an organic residue, a CO as a carbonyl group, and a hydroxylamine as NH2-OH. They are used as metal...

s and carboxylates (e.g. derivatives of citric acid

Citric acid

Citric acid is a weak organic acid. It is a natural preservative/conservative and is also used to add an acidic, or sour, taste to foods and soft drinks...

). Citric acid can also act as a siderophore. The wide variety of siderophores may be due to evolutionary pressures placed on microbes to produce structurally different siderophores which cannot be transported by other microbes' specific active transport systems, or in the case of pathogens deactivated by the host organism.

Diversity

Examples of siderophores produced by various bacteria and fungi:

| Siderophore | Organism |

|---|---|

| ferrichrome Ferrichrome Ferrichrome is a cyclic hexa-peptide that forms a complex with iron atoms.Ferrichrome was first isolated in 1952, has been found to be produced by fungi of the genera Aspergillus, Ustilago, and Penicillium.... |

Ustilago Ustilago Ustilago is a genus of approximately 200 smut fungi parasitic on grasses.There is a large research community that works on Ustilago maydis including researchers at the University of Georgia, Philipps-Universität Marburg, University of British Columbia and others... sphaerogena |

| Desferrioxamine B (Deferoxamine Deferoxamine Deferoxamine is a bacterial siderophore produced by the actinobacteria Streptomyces pilosus. It has medical applications as a chelating agent used to remove excess iron from the body... ) |

Streptomyces Streptomyces Streptomyces is the largest genus of Actinobacteria and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 500 species of Streptomyces bacteria have been described. As with the other Actinobacteria, streptomycetes are gram-positive, and have genomes with high guanine and cytosine content... pilosus Streptomyces Streptomyces Streptomyces is the largest genus of Actinobacteria and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 500 species of Streptomyces bacteria have been described. As with the other Actinobacteria, streptomycetes are gram-positive, and have genomes with high guanine and cytosine content... coelicolor |

| Desferrioxamine E | Streptomyces Streptomyces Streptomyces is the largest genus of Actinobacteria and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 500 species of Streptomyces bacteria have been described. As with the other Actinobacteria, streptomycetes are gram-positive, and have genomes with high guanine and cytosine content... coelicolor |

| fusarinine C | Fusarium Fusarium Fusarium is a large genus of filamentous fungi widely distributed in soil and in association with plants. Most species are harmless saprobes, and are relatively abundant members of the soil microbial community. Some species produce mycotoxins in cereal crops that can affect human and animal health... roseum |

| ornibactin | Burkholderia cepacia |

Catecholate siderophores

| Siderophore | Organism |

|---|---|

| enterobactin Enterobactin Enterobactin is a high affinity siderophore that acquires iron for microbial systems. It is primarily found in Gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium.... |

Escherichia coli Escherichia coli Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms . Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in humans, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls... enteric bacteria |

| bacillibactin | Bacillus subtilis Bacillus subtilis Bacillus subtilis, known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium commonly found in soil. A member of the genus Bacillus, B. subtilis is rod-shaped, and has the ability to form a tough, protective endospore, allowing the organism to tolerate... Bacillus anthracis Bacillus anthracis Bacillus anthracis is the pathogen of the Anthrax acute disease. It is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium, with a width of 1-1.2µm and a length of 3-5µm. It can be grown in an ordinary nutrient medium under aerobic or anaerobic conditions.It is one of few bacteria known to... |

| vibriobactin | Vibrio cholerae Vibrio cholerae Vibrio cholerae is a Gram-negative, comma-shaped bacterium. Some strains of V. cholerae cause the disease cholera. V. cholerae is facultatively anaerobic and has a flagella at one cell pole. V... |

Mixed ligands

| Siderophore | Organism |

|---|---|

| azotobactin Pyoverdine Pyoverdine is a fluorescent siderophore produced by the Gram negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa.In Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 there are 14 pvd genes involed in the synthesis of the pyoveridine.... |

Azotobacter vinelandii Azotobacter vinelandii Azotobacter vinelandii is diazotroph that can fix nitrogen while grown aerobically. It is a genetically tractable system that is used to study nitrogen fixation... |

| pyoverdine Pyoverdine Pyoverdine is a fluorescent siderophore produced by the Gram negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa.In Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 there are 14 pvd genes involed in the synthesis of the pyoveridine.... |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common bacterium that can cause disease in animals, including humans. It is found in soil, water, skin flora, and most man-made environments throughout the world. It thrives not only in normal atmospheres, but also in hypoxic atmospheres, and has, thus, colonized many... |

| yersiniabactin Yersiniabactin Yersiniabactin is a siderophore found in the pathogenic bacteria Yersinia pestis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia enterocolitica, as well as several strains of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Siderophores, compounds of low molecular mass with high affinities for ferric iron, are... |

Yersinia pestis Yersinia pestis Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium. It is a facultative anaerobe that can infect humans and other animals.... |

Some poaceae

Poaceae

The Poaceae is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of flowering plants. Members of this family are commonly called grasses, although the term "grass" is also applied to plants that are not in the Poaceae lineage, including the rushes and sedges...

(grasses) including wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

and barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

produce a class of siderophores called phytosiderophores or mugineic acids.

Biological Function

In response to iron limitation in their environment, genes involved in microbe siderophore production and uptake are derepressed, leading to manufacture of siderophores and the appropriate uptake proteins. In bacteria, Fe2+-dependent repressors bind to DNA upstream to genes involved in siderophore in high intracellular iron concentrations. At low concentrations, Fe2+ dissociates from the repressor, which in turn dissociates from the DNA, leading to transcription of the genes. In gram-negative and AT-rich gram-positive bacteria, this is usually regulated by the Fur (ferric uptake regulator) repressor, whilst in GC-rich gram-positive bacteria (e.g. ActinobacteriaActinobacteria

Actinobacteria are a group of Gram-positive bacteria with high guanine and cytosine content. They can be terrestrial or aquatic. Actinobacteria is one of the dominant phyla of the bacteria....

) it is DtxR (diphtheria toxin repressor), so-called as the production of the dangerous diphtheria toxin

Diphtheria toxin

Diphtheria toxin is an exotoxin secreted by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the pathogen bacterium that causes diphtheria. Unusually, the toxin gene is encoded by a bacteriophage...

by Corynebacterium diphtheriae

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is a pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. It is also known as the Klebs-Löffler bacillus, because it was discovered in 1884 by German bacteriologists Edwin Klebs and Friedrich Löffler .-Classification:Four subspecies are recognized: C. diphtheriae mitis, C....

is also regulated by this system.

This is followed by excretion of the siderophore into the extracellular environment, where the siderophore acts to sequester and solubilize the iron. Siderophores are then recognized by cell specific receptors on the outer membrane of the cell. In fungi and other eukaryotes, the Fe-siderophore complex may be extracellularly reduced to Fe2+, whilst in many cases the whole Fe-siderophore complex is actively transported across the cell membrane. In gram-negative bacteria, these are transported into the periplasm via TonB-dependent receptors

TonB-dependent receptors

TonB-dependent receptors is a family of beta-barrel proteins from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The TonB complex senses signals from outside the bacterial cell and transmits them via two membranes into the cytoplasm, leading to transcriptional activation of target genes.In...

, and is transferred into the cytoplasm by ABC transporters.

Once in the cytoplasm of the cell, the Fe3+-siderophore complex is usually reduced to Fe2+ to release the iron, especially in the case of "weaker" siderophore ligands such as hydroxamates and carboxylates. Siderophore decomposition or other biological mechanisms can also release iron., especially in the case of catecholates such as ferric-enterobactin, whose reduction potential is too low for reducing agents such as flavin adenine dinucleotide, hence enzymatic degradation is needed to release the iron.

Medical Applications

Siderophores have applications in medicine for iron and aluminum overload therapy and antibiotics for better targeting. Understanding the mechanistic pathways of siderophores has led to opportunities for designing small-molecule inhibitors that block siderophore biosynthesis and therefore bacterial growth and virulence in iron-limiting environments.Siderophores are useful as drugs in facilitating iron mobilization in humans, especially in the treatment of iron diseases, due to their high affinity for iron. One potentially powerful application is to use the iron transport abilities of siderophores to carry drugs into cells by preparation of conjugates between siderophores and antimicrobial agents. Because microbes recognize and utilize only certain siderophores, such conjugates are anticipated to have selective antimicrobial activity.

Microbial iron transport (siderophore)-mediated drug delivery makes use of the recognition of siderophores as iron delivery agents in order to have the microbe assimilate siderophore conjugates with attached drugs. These drugs are lethal to the microbe and cause the microbe to apoptosis

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death that may occur in multicellular organisms. Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and chromosomal DNA fragmentation...

e when it assimilates the siderophore conjugate. Through the addition of the iron-binding functional groups of siderophores into antibiotics, their potency has been greatly increased. This is due to the siderophore-mediated iron uptake system of the bacteria.

Agricultural Applications

PoaceaePoaceae

The Poaceae is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of flowering plants. Members of this family are commonly called grasses, although the term "grass" is also applied to plants that are not in the Poaceae lineage, including the rushes and sedges...

(grasses) including agriculturally important species such as barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

and wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

are able to efficiently sequester iron by releasing phytosiderophores via their root

Root

In vascular plants, the root is the organ of a plant that typically lies below the surface of the soil. This is not always the case, however, since a root can also be aerial or aerating . Furthermore, a stem normally occurring below ground is not exceptional either...

into the surrounding soil

Soil

Soil is a natural body consisting of layers of mineral constituents of variable thicknesses, which differ from the parent materials in their morphological, physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics...

rhizosphere

Rhizosphere

The rhizosphere is the narrow region of soil that is directly influenced by root secretions and associated soil microorganisms. Soil which is not part of the rhizosphere is known as bulk soil. The rhizosphere contains many bacteria that feed on sloughed-off plant cells, termed rhizodeposition, and...

. Chemical compounds produced by microorganisms in the rhizosphere can also increase the availability and uptake of iron. Plants such as oats are able to assimilate iron via these microbial siderophores. It has been demonstrated that plants are able to use the hydroxamate-type siderophores ferrichrome, rodotorulic acid and ferrioxamine B; the catechol-type siderophores, agrobactin; and the mixed ligand catechol-hydroxamate-hydroxy acid siderophores biosynthesized by saprophytic root-colonizing bacteria. All of these compounds are produced by rhizospheric bacterial strains, which have simple nutritional requirements, and are found in nature in soils, foliage, fresh water, sediments, and seawater.

Fluorescent pseudomonads have been recognized as biocontrol agents against certain soil-borne plant pathogens. They produce yellow-green pigments (pyoverdines) which fluoresce under UV light and function as siderophores. They deprive pathogens of the iron required for their growth and pathogenesis.

Other Metals Chelated by Siderophores

- Aluminum

- GalliumGalliumGallium is a chemical element that has the symbol Ga and atomic number 31. Elemental gallium does not occur in nature, but as the gallium salt in trace amounts in bauxite and zinc ores. A soft silvery metallic poor metal, elemental gallium is a brittle solid at low temperatures. As it liquefies...

- ChromiumChromiumChromium is a chemical element which has the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in Group 6. It is a steely-gray, lustrous, hard metal that takes a high polish and has a high melting point. It is also odorless, tasteless, and malleable...

- CopperCopperCopper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

- ZincZincZinc , or spelter , is a metallic chemical element; it has the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is the first element in group 12 of the periodic table. Zinc is, in some respects, chemically similar to magnesium, because its ion is of similar size and its only common oxidation state is +2...

- LeadLeadLead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

- ManganeseManganeseManganese is a chemical element, designated by the symbol Mn. It has the atomic number 25. It is found as a free element in nature , and in many minerals...

- CadmiumCadmiumCadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, bluish-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Similar to zinc, it prefers oxidation state +2 in most of its compounds and similar to mercury it shows a low...

- VanadiumVanadiumVanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery gray, ductile and malleable transition metal. The formation of an oxide layer stabilizes the metal against oxidation. The element is found only in chemically combined form in nature...

- IndiumIndiumIndium is a chemical element with the symbol In and atomic number 49. This rare, very soft, malleable and easily fusible post-transition metal is chemically similar to gallium and thallium, and shows the intermediate properties between these two...

- PlutoniumPlutoniumPlutonium is a transuranic radioactive chemical element with the chemical symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, forming a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four oxidation...

- UraniumUraniumUranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...