Sewell's Point

Encyclopedia

Peninsula

A peninsula is a piece of land that is bordered by water on three sides but connected to mainland. In many Germanic and Celtic languages and also in Baltic, Slavic and Hungarian, peninsulas are called "half-islands"....

of land in the independent city

Independent city

An independent city is a city that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity. These type of cities should not be confused with city-states , which are fully sovereign cities that are not part of any other sovereign state.-Historical precursors:In the Holy Roman Empire,...

of Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, located at the mouth of the salt-water port of Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

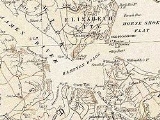

. Sewells Point is bordered by water on three sides, with Willoughby Bay

Willoughby Bay

There are several places called Willoughby Bay. These include:*Willoughby Bay in Virginia, United States*Willougby Bay in Antigua...

to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and the Lafayette River

Lafayette River

The Lafayette River, earlier known as Tanner's Creek, is a tidal estuary which empties into the Elizabeth River just south of Sewell's Point near its mouth at Hampton Roads, which in turn empties into the southern end of Chesapeake Bay in southeast Virginia in the United States...

to the south. It is the site of Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia, is a base of the United States Navy, supporting naval forces in the United States Fleet Forces Command, those operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean...

.

Origins and variations of name

The area was originally named in the 17th century after Henry Sewell, an Englishman who arrived in Virginia sometime prior to 1632 and married Alice Willoughby, daughter of Thomas Willoughby, a prominent magistrate.Later, variations in spelling were used, such as Seawells Point, and Sewall Point. The common spelling today is Sewells Point.

First church in Norfolk

About 1637, the Elizabeth River Parish was created. The first Anglican church of Elizabeth River Parish was erected between 1638 and 1640 "at Mr. Seawell's Pointe," with assistance of Thomas Willouughby. The first recorded minister was the Reverend John Wilson. The second church to be located in the area now known as South Hampton RoadsSouth Hampton Roads

South Hampton Roads is a region located in the extreme southeastern portion of Virginia in the United States, and is part of the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA with a population about 1.7 million....

(the first being St Lukes in Smithfield), it stood somewhere within the present western limits of the US Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia, is a base of the United States Navy, supporting naval forces in the United States Fleet Forces Command, those operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean...

. According to old court records, the Episcopal churches in Norfolk are directly descended from it.

Local government – Shire to County to City – A Virginia tradition

Sewells Point is an area of land, most notable because of its prominence along the eastern shore of the harbor of Hampton Roads. Never declared a town or city, Sewells Point is more correctly described as a geographical area. The listing of political entities which have constituted the local government at Sewells Point is complex, but typical of many communities in the state of VirginiaVirginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

dating back to the colonial period.

During the 17th century, shortly after establishment of Jamestown

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

in 1607, English settlers and explorers began settling the areas adjacent to Hampton Roads. By 1634, the English colony of Virginia consisted of eight shire

Shire

A shire is a traditional term for a division of land, found in the United Kingdom and in Australia. In parts of Australia, a shire is an administrative unit, but it is not synonymous with "county" there, which is a land registration unit. Individually, or as a suffix in Scotland and in the far...

s or counties with a total population of approximately 5,000 inhabitants. Sewells Point was a part of Elizabeth River Shire.

In 1636, the southern portion of Elizabeth River Shire became New Norfolk County, and was divided in 1637 into Upper and Lower Norfolk Counties. In 1691 Lower Norfolk County was in turn divided to form Norfolk County

Norfolk County, Virginia

Norfolk County was a county of the South Hampton Roads in eastern Virginia in the United States that was created in 1691. After the American Civil War, for a period of about 100 years, portions of Norfolk County were lost and the territory of the county reduced as they became parts of the separate...

and Princess Anne County

Princess Anne County, Virginia

Princess Anne County is a former county which was created in the British Colony of Virginia and the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States in 1691. The county was merged into the city of Virginia Beach...

.

Sewells Point was to remain located in Norfolk County for over 225 years, until the independent City of Norfolk annexed the area in 1923. (Virginia has had an independent city

Independent city

An independent city is a city that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity. These type of cities should not be confused with city-states , which are fully sovereign cities that are not part of any other sovereign state.-Historical precursors:In the Holy Roman Empire,...

political subdivision since 1871). The City of South Norfolk

South Norfolk, Virginia

South Norfolk was an independent city in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia and is now a section of the City of Chesapeake, one of the cities of Hampton Roads which surround the harbor of Hampton Roads and are linked by the Hampton Roads Beltway.-History:Located a few miles south of...

and Norfolk County merged to form the new independent city of Chesapeake

Chesapeake, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 199,184 people, 69,900 households, and 54,172 families residing in the city. The population density was 584.6 people per square mile . There were 72,672 housing units at an average density of 213.3 per square mile...

in 1963.

Boundaries determined by weather

Although Hampton RoadsHampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

represents a sheltered area from the tempests of both the Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

and the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

, the area’s shorelines change with extreme weather. At one time, apparently since English settlement began at Jamestown

Jamestown, Virginia

Jamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

in 1607, Willoughby Bay

Willoughby Bay

There are several places called Willoughby Bay. These include:*Willoughby Bay in Virginia, United States*Willougby Bay in Antigua...

did not border Sewells Point to the north, since it didn't even exist yet.

The area known as Willoughby takes its name from Thomas Willoughby, who came to Virginia in 1610 and received a land grant

Land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate – land or its privileges – made by a government or other authority as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service...

around 1625. Willoughby's son, Thomas II, was living there in the 1660s. According to local legend, his wife awoke one morning following a terrific storm (possibly the "Harry Cane" of 1667) to see a point of land in front her home, where there had been only water the night before. The Willoughby family, it is said, were quick to apply for an addendum to the original land grant

Land grant

A land grant is a gift of real estate – land or its privileges – made by a government or other authority as a reward for services to an individual, especially in return for military service...

, giving them ownership of the "new" property.

Severe storms and hurricanes would continue to transform the contour of the coast, and the Willoughby holdings, for more than a century. Although official records of Hampton Roads weather go back only to 1871 when the National Weather Service

National Weather Service

The National Weather Service , once known as the Weather Bureau, is one of the six scientific agencies that make up the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States government...

office was established in downtown Norfolk, records of earlier storms have been located in ships' logs, newspaper accounts, history books and writings of early settlers.

Residents of coastal Virginia in the colonial period (1607–1776) were very much aware of the weather. To people who lived near the water and derived much of their livelihood from the sea, a tropical storm was a noteworthy event. During a hurricane in 1749, the Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

rose 15 feet (4.6 m) above normal, sand spit was washed up at Sewells Point. With the help of the Great Coastal Hurricane of 1806, Willoughby Spit

Willoughby Spit

Willoughby Spit is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States. It is bordered by water on three sides: the Chesapeake Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and Willoughby Bay to the south.- History :...

was formed. The area of water now located between Sewells Point and Willoughby Spit became known as Willoughby Bay.

A strategic Civil War location

Sewells Point's location at the mouth of Hampton Roads proved to be a strategic location during the early portion of the Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Battle of Sewells Point

The first skirmish in Virginia, the little-known Battle of Sewells PointBattle of Sewell's Point

The Battle of Sewell's Point was an inconclusive exchange of cannon fire between the Union gunboat USS Monticello, supported by the USS Thomas Freeborn, and Confederate batteries on Sewell's Point that took place on May 18, 19 and 21, 1861, in Norfolk County, Virginia in the early days of the...

, was fought on May 18–19, 1861, on ground now occupied by the US Naval Station Norfolk. The events leading up to the initial engagement on Virginia soil had moved with whirlwind rapidity.

Events leading onto the Battle

On December 20, 1860, South CarolinaSouth Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

became the first state to secede from the Union. Four months later, on April 12, 1861, troops of that state opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

's harbor. Five days later, Virginia became the eighth Southern state to withdraw from the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

, and join the newly formed Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

.

A few weeks later that spring, US General-in-Chief Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

proposed to President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

a plan to bring the states back into the Union: cut the Confederacy off from the rest of the world instead of attacking its army in Virginia.

His plan was to blockade the Confederacy's coastline and control the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

valley with gunboats. Lincoln ordered a blockade of the southern seaboard from the South Carolina line to the Rio Grande on April 19 and on April 27 extended it to include the North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

and Virginia coasts. On April 20, the Union Navy burned and evacuated the Norfolk Navy Yard, destroying nine ships in the process, leaving only Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe was a military installation in Hampton, Virginia—at Old Point Comfort, the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula...

at Old Point Comfort as the last bastion of the United States in Tidewater Virginia.

Occupation of Norfolk gave the Confederacy its only major shipyard and thousands of heavy guns, but they held it for only one year. CS Brigadier General Walter Gwynn

Walter Gwynn

Walter Gwynn was a civil engineer and soldier who became a Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, who commanded the Confederate defenses around Norfolk, erected batteries at Sewells Point, both to protect Norfolk and to control Hampton Roads.

The Union dispatched a fleet to Hampton Roads to enforce the blockade, and on May 18–19 Federal gunboats exchanged fire with the batteries at Sewells Point, resulting in little damage to either side.

The Battle Itself

Stewart's "History of Norfolk County, Virginia" (1902), contains a detailed account of the Battle of Sewells Point that took place one month later.- "On May 18, 1861, Norfolk-area and Georgia Confederate troops began erecting land batteries at Sewells Point opposite Fort Monroe on Hampton Roads. By 5 o'clock that evening, three guns and two rifled guns had been mounted and work was rapidly progressing on the fortifications when the USS MonticelloUSS Monticello (1859)The first USS Monticello was a wooden screw-steamer in the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She was named for the home of Thomas Jefferson. She was briefly named Star in May 1861....

, commanded by Captain Henry Eagle, steamed over from Fort Monroe to see what was afoot. Not liking what he saw, Captain Eagle gave the order to open fire. One of the shots from his vessel hit the battery, throwing turf high in the air. In the meantime, the Monticello had been joined by an armed tug, also from Fort Monroe. The bombardment from these two vessels caused momentary confusion in the breastworks, but once the Confederates had recovered from the initial shock, immediate preparations were made to return the fire from their two 32-pounders and the two rifled guns already in position. In the absence of a Confederate or Virginia flag, Captain Peyton H. Colquitt of the Light Guard of Columbus, GeorgiaColumbus, GeorgiaColumbus is a city in and the county seat of Muscogee County, Georgia, United States, with which it is consolidated. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 189,885. It is the principal city of the Columbus, Georgia metropolitan area, which, in 2009, had an estimated population of 292,795...

, who was in charge of the erection of the battery, called for the raising of the Georgia flag on the Sewells Point ramparts. Under the cover of darkness, the armed tug returned to Fort Monroe, but the Monticello remained off Sewells Point with her guns pointed in the direction of the Confederate fortifications".

- "During the night, frantic efforts were made to complete the breastworks, and it was not until the next day at around 5:50 in the afternoon that the bombardment was resumed. It continued until 6:45 p.m. In the end, the Monticello, with several gaping holes in her hull from well-aimed Confederate shots limped back to Fort Monroe. The first engagement on Virginia soil during the Civil War was over."

There were no fatalities on either side. The only person wounded was a Confederate private who was struck by a fragment of a bursting shell. Subsequently the Sewells Point batteries were under fire many times, but they were never silenced or captured in combat. And, later, when Confederate forces evacuated Norfolk on May 10, 1862, they were abandoned.

Battle of Hampton Roads

The famous Battle of Hampton RoadsBattle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, often referred to as either the Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack or the Battle of Ironclads, was the most noted and arguably most important naval battle of the American Civil War from the standpoint of the development of navies...

took place off Sewells Point in Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

on March 8–9, 1862.

USS Monitor

USS Monitor

USS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She is most famous for her participation in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the first-ever battle fought between two ironclads...

of the Union Navy

Union Navy

The Union Navy is the label applied to the United States Navy during the American Civil War, to contrast it from its direct opponent, the Confederate States Navy...

faced CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia was the first steam-powered ironclad warship of the Confederate States Navy, built during the first year of the American Civil War; she was constructed as a casemate ironclad using the raised and cut down original lower hull and steam engines of the scuttled . Virginia was one of the...

of the Confederate States Navy

Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy was the naval branch of the Confederate States armed forces established by an act of the Confederate Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American Civil War...

.

The battle, which was inconclusive, is chiefly significant in naval history as the first battle between two powered ironclad warships, which came to be known as ironclads.

Abraham Lincoln and the bombardment of Sewells Point

On May 5, 1862, President Lincoln, with his Cabinet Secretaries StantonEdwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865...

and Chase

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase was an American politician and jurist who served as U.S. Senator from Ohio and the 23rd Governor of Ohio; as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Abraham Lincoln; and as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.Chase was one of the most prominent members...

on board, proceeded to Hampton Roads on steamer Miami to personally direct the stalled Peninsular Campaign. The following day, Lincoln directed gunboat operations in the James River

James River (Virginia)

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia. It is long, extending to if one includes the Jackson River, the longer of its two source tributaries. The James River drains a catchment comprising . The watershed includes about 4% open water and an area with a population of 2.5 million...

and the bombardment of Sewells Point by the blockading squadron in the five days he acted as Commander-in-Chief in the field.

On May 8, 1862, Monitor

USS Monitor

USS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She is most famous for her participation in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the first-ever battle fought between two ironclads...

, Dacotah, Naugatuck, Seminole, and Susquehanna by direction of the President "-shelled Confederate batteries at Sewells Point, Virginia, as Flag Officer L. M. Goldsborough reported, "mainly with the view of ascertaining the practicability of landing a body of troops thereabouts" to move on Norfolk. Whatever rumors President Lincoln had received about Confederates abandoning Norfolk were now confirmed; a tug deserted and brought news that the evacuation was well underway and that CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia was the first steam-powered ironclad warship of the Confederate States Navy, built during the first year of the American Civil War; she was constructed as a casemate ironclad using the raised and cut down original lower hull and steam engines of the scuttled . Virginia was one of the...

, with her accompanying small gunboats, planned to proceed up the James River or York River

York River (Virginia)

The York River is a navigable estuary, approximately long, in eastern Virginia in the United States. It ranges in width from at its head to near its mouth on the west side of Chesapeake Bay. Its watershed drains an area including portions of 17 counties of the coastal plain of Virginia north...

.

It was planned that when the Virginia came out, as she had on the 7th, the Union fleet would retire with the Monitor in the rear hoping to draw the powerful but under-engined warship into deep water where she might be rammed by high speed steamers. The bombardment uncovered reduced but still considerable strength at Sewells Point. The Virginia came out but not far enough to be rammed.

Two days later, President Lincoln, still acting as Commander-in-Chief, directed Flag Officer Goldsborough: "If you have tolerable confidence that you can successfully contend with the Merrimac [Lincoln and the North used the ships' former name] without the help of the Galena and two accompanying gunboats, send the Galena and two gunboats up the James River at once to support General McClellan." This division power afloat by the President silenced two shore batteries and forced gunboats CSS Jamestown and CSS Patrick Henry to return up the James River.

On May 9, 1862, President Lincoln himself, after talking to pilots and studying charts, reconnoitered to the eastward of Sewells Point and found a suitably unfortified landing site near Willoughby Point. The troops embarked in transports that night. The next morning they landed near the site selected by the President. The latter, still afloat, from his "command ship" Miami ordered the Monitor to reconnoiter Sewells Point to learn if the batteries were still manned. When he found the works abandoned, President Lincoln ordered Major General Wool's troops to march on Norfolk, where they arrived late on the afternoon of the 10th.

On May 10, 1862, Norfolk Navy Yard was set afire before being evacuated by Confederate forces in a general withdrawal up the peninsula to defend Richmond. Union troops crossed Hampton Roads from Fort Monroe, landed at Ocean View, and captured Norfolk. With the entire area back under Union control, the isolated batteries at Sewells Point lost their importance and were abandoned. For the remainder of the 19th century, the area was largely undeveloped and sparsely populated.

Sewells Point in the 20th century

Early in the 20th century, two developments at Sewells Point would have a long-lasting effect on its role in US history. Each laid the groundwork for founding of what was to become the world’s largest naval base.The first could be described as a civilian battle, one of competition, between the growing railroad and industrial powers. The other had its beginning as a civilian celebration. These were the building of the Virginian Railway

Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

and the Jamestown Exposition

Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

.

Building the Virginian Railway

In the mid-1890s, William N. PageWilliam N. Page

William Nelson Page was an American civil engineer, entrepreneur, industrialist and capitalist. He was active in the Virginias following the U.S. Civil War...

, a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

who had previously worked building the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P...

(C&O) had a dream. He knew of rich untapped bituminous coal

Bituminous coal

Bituminous coal or black coal is a relatively soft coal containing a tarlike substance called bitumen. It is of higher quality than lignite coal but of poorer quality than Anthracite...

fields lying between the New River Valley

New River Valley

The New River Valley is a region in the eastern United States along the New River in the Commonwealth of Virginia . The valley comprises the counties of Montgomery , Pulaski, Floyd, Giles and the independent City of Radford...

and the lower Guyandotte River

Guyandotte River

The Guyandotte River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 166 mi long, in southwestern West Virginia in the United States. It was named after the French term for the Wendat Native Americans...

in southern West Virginia

West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian and Southeastern regions of the United States, bordered by Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Ohio to the northwest, Pennsylvania to the northeast and Maryland to the east...

in an area not yet reached by the C&O and its major competitor, the Norfolk and Western Railway

Norfolk and Western Railway

The Norfolk and Western Railway , a US class I railroad, was formed by more than 200 railroad mergers between 1838 and 1982. It had headquarters in Roanoke, Virginia for most of its 150 year existence....

(N&W).

While the bigger railroads which were busy developing nearby areas and shipping coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

via rail to Hampton Roads, he formed a plan. To take advantage of the undeveloped coal lands, Page enlisted several friends as investors to help purchase the land. In 1898, he acquired a small logging railroad, and converted and expanded it to become the intrastate (within West Virginia only) Deepwater Railway. The new short-line railroad planned to connect with the existing lines of the C&O along the Kanawha River

Kanawha River

The Kanawha River is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, it has formed a significant industrial region of the state since the middle of the 19th century.It is formed at the town of Gauley...

at Deepwater and the N&W at Matoaka.

As Page developed his Deepwater Railway

Deepwater Railway

The Deepwater Railway was an intrastate short line railroad located in West Virginia in the United States which operated from 1898 to 1907.William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, had begun a small logging railroad in Fayette County in 1896, sometimes called the Loup Creek and Deepwater...

, he ran into a wall in negotiating to make connections and share favorable rates with either of the larger railroads. It was later revealed that the leaders of both the C&O and the N&W considered the territory to be potentially theirs for future growth. They secretly agreed to refuse to negotiate with Page and his upstart Deepwater Railway.

Page didn't give up as apparently was anticipated. Instead, he stubbornly continued building his Deepwater Railroad, to the increasing puzzlement of the two big railroads. They were unaware that one of Page's investors, who were silent partners in the venture, was financier and industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

, a millionaire who had made his initial fortune as one of the key men with the Standard Oil

Standard Oil

Standard Oil was a predominant American integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company. Established in 1870 as a corporation in Ohio, it was the largest oil refiner in the world and operated as a major company trust and was one of the world's first and largest multinational...

Trust. Rogers wasn't about to have the investment foiled by the big railroads. Instead, he and Page set about secretly planning and securing their own route out of the mountains, all the way east across Virginia to Hampton Roads!

A separate company, the Tidewater Railway

Tidewater Railway

The Tidewater Railway was formed in 1904 as an intrastate railroad in Virginia, in the United States, by William N. Page, a civil engineer and entrepreneur, and his silent partner, millionaire industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers of Standard Oil fame...

, was formed in Virginia for the portion to be in that state. Both planning and land acquisition were done largely in secret. One group of 35 surveyors posing as fishermen (on a Sunday in February!) mapped out a crossing of the New River at Glen Lyn, Virginia

Glen Lyn, Virginia

Glen Lyn is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the East and New Rivers. The population was 151 at the 2000 census...

, as well as the adjacent portion of the line from West Virginia through Narrows, Virginia

Narrows, Virginia

Narrows, named for the narrowing of the New River that flows past it, is a town in Giles County, Virginia, United States. The population was 2,111 at the 2000 census...

. The new line essentially followed the valley of the Roanoke River

Roanoke River

The Roanoke River is a river in southern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina in the United States, 410 mi long. A major river of the southeastern United States, it drains a largely rural area of the coastal plain from the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains southeast across the Piedmont...

through the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

, and then was to run almost due east to the Hampton Roads area.

Deals were quietly struck with the various communities all along the way. Perhaps most notable of all of these communities, was Norfolk, which was home-turf for the established Norfolk & Western Railway and its coal pier at Lambert's Point

Lambert's Point

Lamberts Point is a point of land on the south shore of the Elizabeth River near the downtown area of the independent city of Norfolk in the South Hampton Roads region of eastern Virginia, United States...

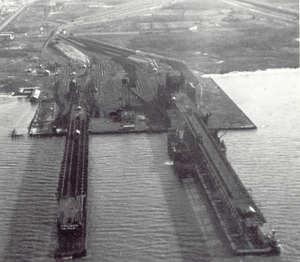

. Access to Hampton Roads frontage with enough adjoining land to build a new coal pier was crucial to the whole scheme. Undeveloped land was located at Sewells Point where the Page-Rogers interests purchased 1000 feet (304.8 m) of frontage on Hampton Roads, and adjoining land. To facilitate building of the new railroad, Norfolk provided a right-of-way extending virtually completely around the city to reach Sewells Point.

With their land and route secured, in 1905, Page (with Rogers' identity still not revealed) began building the rest of the new railroad. By the time the larger railroads finally realized what was happening, their new competitor could not be successfully blocked. Rogers' identity and backing were finally disclosed more than a year later. Early in 1907, the Deepwater and Tidewater Railways, still under construction, were combined to become the Virginian Railway

Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

(VGN).

Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

, which was held on land just north of the VGN coal pier site at Sewells Point, which opened in the spring of 1907.

By using construction techniques not available when the larger railroads had been built about 25 years earlier, and paying for work with Rogers' own personal fortune, the new Virginian Railway was built to the highest standards. An engineering marvel of the day, the final spike in the VGN was driven on January 29, 1909.

In April 1909, Rogers was feted at Norfolk in celebration of the completion his new "Mountains to the Sea" railroad. He toured the railway’s new $2.5 million coal pier at Sewells Point and Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

spoke at a grand Norfolk banquet.

The Virginian Railway and its terminal location at Sewells Point played an important role in 20th century US naval history. Located immediately adjacent to the former Exposition grounds (which became an important Navy facility beginning in 1917) the VGN transported the high quality smokeless bituminous coal favored by the US Navy for its ships.

When the VGN was merged with the Norfolk & Western in 1959, civilian coal loading was shifted to Lambert's Point, and the Navy purchased the site a few years later. The former VGN Sewells Point site is now part of the United States' Naval Station Norfolk.

Jamestown Exposition of 1907

The Jamestown ExpositionJamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

was one of the many world's fair

World's Fair

World's fair, World fair, Universal Exposition, and World Expo are various large public exhibitions held in different parts of the world. The first Expo was held in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, United Kingdom, in 1851, under the title "Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All...

s and exposition

Trade fair

A trade fair is an exhibition organized so that companies in a specific industry can showcase and demonstrate their latest products, service, study activities of rivals and examine recent market trends and opportunities...

s that were popular in the United States early part of the 20th century. It was held from April 26 to December 1, 1907, at Sewells Point to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Settlement in 1607.

Early in the 20th century, as the tercentennial neared, leaders in Norfolk began a campaign to have a celebration held there. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities had gotten the ball rolling in 1900 by calling for a celebration honoring the establishment of the first permanent English colony in the New World at Jamestown, to be held on the 300th anniversary.

No one thought that the actual isolated and long-abandoned original site at Jamestown Island would be suitable. Jamestown had no facilities for large crowds, and the fort housing the Jamestown Settlement was believed to have been long-ago swallowed by the James River. However, there was an assumption in many parts of the state that Richmond, the state capital, would be chosen as the site of the celebration.

Hampton Roads' interest was awakened by an editorial in James M. Thomson's Norfolk Dispatch, on February 4, 1901, proclaiming: "Norfolk is undoubtedly the proper place for the holding of this celebration. Norfolk is today the center of the most populous portion of Virginia, and every historical, business and sentimental reason can be adduced in favor of the celebration taking place here rather than in Richmond."

The Dispatch was an unrelenting champion of Norfolk as the site for the exposition, noting in subsequent editorials that "Richmond has absolutely no claim to the celebration except her location on the James River."

By September 1901, the Norfolk City Council had given support to the project and in December, 100 prominent residents of Hampton Roads journeyed to Richmond to urge Norfolk as the site. In 1902, the Jamestown Exposition Co. was incorporated. Former Virginia Governor Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh Lee

Fitzhugh Lee , nephew of Robert E. Lee, was a Confederate cavalry general in the American Civil War, the 40th Governor of Virginia, diplomat, and United States Army general in the Spanish-American War.-Early life:...

, nephew of General Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

, was named its president.

The decision was made to locate the international exposition on a mile-long frontage at Sewells Point. The location was politically correct, as it was almost an equal distance from the cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth

Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth is located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of the U.S. Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2010, the city had a total population of 95,535.The Norfolk Naval Shipyard, often called the Norfolk Navy Yard, is a historic and active U.S...

, Newport News

Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city located in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area of Virginia. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the north shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News...

and Hampton

Hampton, Virginia

Hampton is an independent city that is not part of any county in Southeast Virginia. Its population is 137,436. As one of the seven major cities that compose the Hampton Roads metropolitan area, it is on the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula. Located on the Hampton Roads Beltway, it hosts...

. Rural Sewells Point was also not conveniently located near any one of them. While hard to reach by land, it was more favorably accessible by water, which ultimately proved an asset.

The Jamestown Exposition proved to be a logistical nightmare. Roads had to be built to the site. Piers had to be constructed for moving supplies to exposition buildings. Hotels had to be raised to handle the exposition visitors, almost 3 million by the November closing. Bad weather slowed everything.

Another major setback was the death of Fitzhugh Lee. He died while in New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

drumming up trade for the celebration. Henry St. George Tucker, another former Virginia Congressman, succeeded him. Norfolk businessman David Lowenberg ran most of the operation as director general.

Opening day had its share of headaches. Only a fifth of the electric lights could be turned on, and the Warpath recreation area was far from ready. Construction of the government pier left much of the ground in the center of the exposition muddy soup.

But in time, things improved and the event became spectacular. Planners asked each state of the union to contribute a house to celebrate its history and industry. Lack of interest or funds prevented participation by all, but 21 states funded houses, which bore their names: Pennsylvania House, Virginia House, New Hampshire House, North Carolina House, etc. During the exposition, days were set aside to honor the states individually. The governor of the state usually appeared to greet visitors to the state's house. Thirteen of the state houses can still be seen on Dillingham Boulevard at the Naval Station Norfolk, on what has been called "Admiral's Row." Many of them are now residences of high-ranking Navy officers.

US President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

was an honored guest. Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

and Henry H. Rogers

Henry H. Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers was a United States capitalist, businessman, industrialist, financier, and philanthropist. He made his fortune in the oil refinery business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil....

also paid a visit, in the latter's yacht "Kanawha". Twain's humorous talk was partly an introduction of Rear Admiral Purnell F. Harrington, former Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard. Said Twain, "In my remarks of welcome of Admiral Harrington, I am not going to give him compliments. Compliments always embarrass a man. You do not know what to say. It does not inspire you with words. There is nothing you can say in answer to a compliment. I have been complimented myself a great many times, and they always embarrass me. I always feel they have not said enough."

Although the exposition was a financial failure, it served an American purpose and one for Norfolk and Hampton Roads.

Perhaps the exposition's most impressive display was on water rather than land. Ships of two squadrons commanded by Admiral Robley Evans formed a continuing presence off Sewells Point. The assembly included sixteen battleships, five cruisers, and six destroyers. The fleet remained in Hampton Roads after the exposition closed and became President Roosevelt's Great White Fleet

Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the United States Navy battle fleet that completed a circumnavigation of the globe from 16 December 1907 to 22 February 1909 by order of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. It consisted of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with...

, which toured the globe as evidence of the nation's military might. Nearly every Congressman and Senator of prominence had attended the exposition, and Admirals in Norfolk urged the creation of a Naval Base at the exposition site. However, nearly 10 years would elapse before the idea, given impetus by World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, would become a reality.

On June 28, 19l7, President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

set aside $2.8 million for land purchase and the erection of storehouses and piers for the base. Of the 474 acres (1.9 km²) originally acquired, 367 had been the old Jamestown Exposition grounds. The military property was later expanded considerably. The former Virginian Railway coal piers, land, and an adjacent coal storage facility owned by Norfolk & Western Railway were added in the 1960s and 1970s.

Sewells Point in the 21st century

Naval Station NorfolkNaval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia, is a base of the United States Navy, supporting naval forces in the United States Fleet Forces Command, those operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean...

currently occupies Sewells Point. The base is approximately 4000 acres (16.2 km²) and is the largest naval base in the world.

The headquarters of the 5th Naval District, the Atlantic Fleet

U.S. Atlantic Fleet

The United States Fleet Forces Command is an Atlantic Ocean theater-level component command of the United States Navy that provides naval resources that are under the operational control of the United States Northern Command...

, the 2nd Fleet, and the NATO Allied Command Transformation

Allied Command Transformation

Allied Command Transformation is a NATO military command, which was formed in 2003 after North Atlantic Treaty Organisation restructuring....

are there. The Naval Complex includes Naval Station Norfolk, NAS Norfolk, as well as other Naval Facilities of the Hampton Roads area.

When the 78 ships and 133 aircraft home ported there are not at sea, they are alongside one of the 14 piers or inside one of the 15 aircraft hangars for repair, refit, training and to provide the ship's or squadron's crew an opportunity to be with their families. The base is home port to aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, large amphibious ships, submarines, and a variety of supply and logistics ships. Port Services controls more than 3,100 ships' movements annually as they arrive and depart their berths. Port facilities extend more than four miles (6 km) along the waterfront and include some seven miles (11 km) of pier and wharf space.

See also

- Hampton RoadsHampton RoadsHampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

- Battle of Hampton RoadsBattle of Hampton RoadsThe Battle of Hampton Roads, often referred to as either the Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack or the Battle of Ironclads, was the most noted and arguably most important naval battle of the American Civil War from the standpoint of the development of navies...

- Jamestown ExpositionJamestown ExpositionThe Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century...

- Virginian RailwayVirginian RailwayThe Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads....

- Norfolk Navy BaseNaval Station NorfolkNaval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia, is a base of the United States Navy, supporting naval forces in the United States Fleet Forces Command, those operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean...

- Willoughby SpitWilloughby SpitWilloughby Spit is a peninsula of land in the independent city of Norfolk, Virginia in the United States. It is bordered by water on three sides: the Chesapeake Bay to the north, Hampton Roads to the west, and Willoughby Bay to the south.- History :...

- Ocean View

- City of NorfolkNorfolk, VirginiaNorfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 242,803 as of the 2010 Census, it is Virginia's second-largest city behind neighboring Virginia Beach....

- Norfolk CountyNorfolk County, VirginiaNorfolk County was a county of the South Hampton Roads in eastern Virginia in the United States that was created in 1691. After the American Civil War, for a period of about 100 years, portions of Norfolk County were lost and the territory of the county reduced as they became parts of the separate...

Numbered References

- J. D. Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland. Baltimore: Kohn & Pollock, 1905, p. 135.

External links

- Library of Virginia official website

- Virginia Historical Society official website

- Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, VA official website

- City of Norfolk Sewells Point 1923 Annexation

- USS Monitor Center and Exhibit Newport News, Virginia

- Mariner's Museum, Newport News, Virginia

- Hampton Roads Naval Museum

- Norfolk City Historical Society

- Norfolk County Historical Society

- Norfolk Public Library – History of Willoughby

- Norfolk Public Library – History of Weather Events

- City of Norfolk website, Local History

- Civil War and the Battle of Sewell’s Point

- Civil War Naval History

- History of Fort Wool

- "When the World came to Town"

- Naval Station Norfolk website

- Norfolk & Western Historical Society. – Covers Virginian history

- Virginia Museum of Transportation. – Displays 2 of only 3 extant VGN steam and electric locomotives, located in Roanoke, VA

- Virginian Railway (VGN) Enthusiasts. – Non-profit group of preservationists, authors, photographers, historians, modelers, and railfans

- listing of Virginian Railway authors and their works