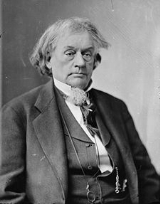

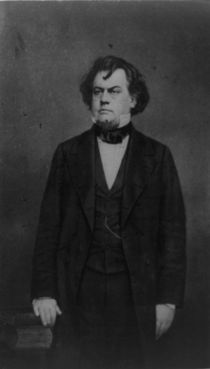

Robert Toombs

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

political leader, United States Senator from Georgia, 1st Secretary of State of the Confederacy, and a Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

general in the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Early life

Born near WashingtonWashington, Georgia

Washington is a city in Wilkes County, Georgia, United States. The population was 4,295 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Wilkes County...

, Wilkes County, Georgia

Wilkes County, Georgia

Wilkes County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia. As of 2000, the population was 10,687. The 2007 Census estimate shows a population of 10,262. The county seat is the city of Washington. Referred to as "Washington-Wilkes", the county seat and county are commonly treated as a...

, Robert Augustus Toombs was the fifth child of Catherine Huling and Robert Toombs. His father died when he was five, and he entered Franklin College

Franklin College of Arts and Sciences

The Franklin College of Arts and Sciences is the founding college of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia, United States. The college was named in honor of Benjamin Franklin.-History:...

at the University of Georgia

University of Georgia

The University of Georgia is a public research university located in Athens, Georgia, United States. Founded in 1785, it is the oldest and largest of the state's institutions of higher learning and is one of multiple schools to claim the title of the oldest public university in the United States...

in Athens

Athens, Georgia

Athens-Clarke County is a consolidated city–county in U.S. state of Georgia, in the northeastern part of the state, comprising the former City of Athens proper and Clarke County. The University of Georgia is located in this college town and is responsible for the initial growth of the city...

when he was just fourteen. During his time at Franklin College he was a member of the Demosthenian Literary Society

Demosthenian Literary Society

The Demosthenian Literary Society is a debating society at The University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia. It was founded in 1803 by the first graduating class of the University's Franklin College. The society was founded on February 19, 1803 and the anniversary is celebrated now with the Society's...

, which honors him as one of its most legendary alumni to this day. After the university chastised him for unbecoming conduct in a card-playing incident, Toombs continued his education at Union College

Union College

Union College is a private, non-denominational liberal arts college located in Schenectady, New York, United States. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents. In the 19th century, it became the "Mother of Fraternities", as...

, in Schenectady, New York

Schenectady, New York

Schenectady is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 66,135...

, from which he graduated in 1828. Toombs went on to study law at the University of Virginia

University of Virginia

The University of Virginia is a public research university located in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, founded by Thomas Jefferson...

Law School in Charlottesville

Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville is an independent city geographically surrounded by but separate from Albemarle County in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States, and named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of King George III of the United Kingdom.The official population estimate for...

. Shortly after his admission to the Georgia bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

, he married his childhood sweetheart, Julia A. Dubose, with whom he had three children.

Public service

Toombs was admitted to the bar in 1830, and served in the Georgia House of RepresentativesGeorgia House of Representatives

The Georgia House of Representatives is the lower house of the Georgia General Assembly of the U.S. state of Georgia.-Composition:...

(1838, 1840–1841, and 1843–1844). His genial character, proclivity for entertainment, and unqualified success on the legal circuit earned Toombs the growing attention and admiration of his fellow Georgians. On the wave of his growing popularity, Toombs won a seat to the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

(1844–1853), and joined his close friend and fellow representative Alexander H. Stephens from Crawfordville, Georgia

Crawfordville, Georgia

Crawfordville is a city in Taliaferro County, Georgia, United States. The population was 572 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Taliaferro County.-Geography:Crawfordville is located at ....

. Their friendship forged a powerful personal and political bond that effectively defined and articulated Georgia's position on national issues in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Toombs, like Stephens, emerged as a states' rights partisan, became a national Whig, and once the Whig Party dissolved, aided in the creation of the short-lived Constitutional Union Party in the early 1850s.

Toombs stood with most Whigs regarding the status of Texas

Texas

Texas is the second largest U.S. state by both area and population, and the largest state by area in the contiguous United States.The name, based on the Caddo word "Tejas" meaning "friends" or "allies", was applied by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves and to the region of their settlement in...

as the 28th state. Historian William Y. Thompson

William Y. Thompson

William Young Thompson is a retired historian who was affiliated for most of his academic career, from 1955 through 1988, with Louisiana Tech University at Ruston in Lincoln Parish, Louisiana...

writes that Toombs was "prepared to vote all necessary supplies to repel invasion. But he did not agree that the territory between the Nueces

Nueces River

The Nueces River is a river in the U.S. state of Texas, approximately long. It drains a region in central and southern Texas southeastward into the Gulf of Mexico. It is the southernmost major river in Texas northeast of the Rio Grande...

and the Rio Grande

Rio Grande

The Rio Grande is a river that flows from southwestern Colorado in the United States to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way it forms part of the Mexico – United States border. Its length varies as its course changes...

rivers was a part of Texas. He declared the movement of American forces to the Rio Grande at President Polk

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk was the 11th President of the United States . Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. He later lived in and represented Tennessee. A Democrat, Polk served as the 17th Speaker of the House of Representatives and the 12th Governor of Tennessee...

's command 'was contrary to the laws of this country, a usurpation on the rights of this House, and an aggression on the rights of Mexico."

From 1853 to 1861 Toombs served in the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, only reluctantly joining the Democratic Party when lack of interest among other states doomed the Constitutional Union Party.

From Unionist to Confederate

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Toombs fought to reconcile national policies with sectional interests. He had opposed the Annexation of Texas but vowed to defend the new state once it was annexed late in 1845. He also opposed the Mexican-American War, President PolkJames K. Polk

James Knox Polk was the 11th President of the United States . Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. He later lived in and represented Tennessee. A Democrat, Polk served as the 17th Speaker of the House of Representatives and the 12th Governor of Tennessee...

's Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

policy, the Walker Tariff

Walker tariff

The Walker Tariff was a set of tariff rates adopted by the United States in 1846. The Walker Tariff was enacted by the Democrats, and made substantial cuts in the high rates of the "Black Tariff" of 1842, enacted by the Whigs. It was based on a report by Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker...

of 1846 and the Wilmot Proviso

Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso, one of the major events leading to the Civil War, would have banned slavery in any territory to be acquired from Mexico in the Mexican War or in the future, including the area later known as the Mexican Cession, but which some proponents construed to also include the disputed...

, first introduced in 1846. In common with Alexander H. Stephens and Howell Cobb

Howell Cobb

Howell Cobb was an American political figure. A Southern Democrat, Cobb was a five-term member of the United States House of Representatives and Speaker of the House from 1849 to 1851...

, he defended Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

's Compromise of 1850

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

against southerners who advocated secession

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

from the Union as the only solution to sectional tensions over slavery. He denounced the Nashville Convention

Nashville Convention

The Nashville Convention was a political meeting held in Nashville, Tennessee, on June 3 – 11, 1850. Delegates from nine slave holding states met to consider a possible course of action if the United States Congress decided to ban slavery in the new territories being added to the country as a...

, opposed the secessionists in Georgia, and helped to frame the famous Georgia platform

Georgia Platform

The Georgia Platform was a statement executed by a Georgia Convention in response to the Compromise of 1850. Supported by Unionists, the document affirmed the acceptance of the Compromise as a final resolution of the sectional slavery issues while declaring that no further assaults on Southern...

(1850). His position and that of Southern Unionists during the decade 1850–1860 has often been misunderstood. They disapproved of secession, not because they considered it wrong in principle, but because they considered it inexpedient.

Toombs objected to halting the spread of slavery into the territories of California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

and New Mexico

New Mexico

New Mexico is a state located in the southwest and western regions of the United States. New Mexico is also usually considered one of the Mountain States. With a population density of 16 per square mile, New Mexico is the sixth-most sparsely inhabited U.S...

and even the abolishment of what John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

had called the "peculiar institution

Peculiar institution

" peculiar institution" was a euphemism for slavery and the economic ramifications of it in the American South. The meaning of "peculiar" in this expression is "one's own", that is, referring to something distinctive to or characteristic of a particular place or people...

" in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

He took the view that the territories were the common property of all the people of the United States and that Congress must insure equal treatment to both slaveholder and non-slaveholder. Were the rights of the South violated, Toombs declared, "Let discord reign forever."

Toombs favored the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Kansas-Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opening new lands for settlement, and had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by allowing settlers in those territories to determine through Popular Sovereignty if they would allow slavery within...

, the admission of Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

under the Lecompton Constitution

Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution was the second of four proposed constitutions for the state of Kansas . The document was written in response to the anti-slavery position of the 1855 Topeka Constitution of James H. Lane and other free-state advocates...

, and the English Bill

English Bill

The English Bill was an offer made by the United States Congress to Kansas Territory. Kansas was offered some millions of acres of public lands in exchange for accepting the Lecompton Constitution....

(1858). However, his faith in the resiliency and effectiveness of the national government to resolve sectional conflicts waned as the 1850s drew to a close.

On June 24, 1856, Toombs introduced in the Senate the Toombs Bill, which proposed a constitutional convention in Kansas under conditions which were acknowledged by various anti-slavery leaders as fair, and which mark the greatest concessions made by the pro-slavery senators during the Kansas struggle. The bill did not provide for the submission of the constitution to popular vote, and the silence on this point of the territorial law under which the Lecompton Constitution of Kansas was framed in 1857 was the crux of the Lecompton struggle.

Thompson refers to Toombs as "hardly a man of the people with his wealth and imperious manner. But his handsome imposing appearance, undoubted ability, and boldness of speech appealed to Georgians, who kept him in national office until the Civil War brought him home."

Secession and Civil War

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

, and on December 22, soon after the election of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

, sent a telegram to Georgia that asserted that "secession by the 4th of March next should be thundered forth from the ballot-box by the united voice of Georgia." He delivered a farewell address in the Senate (January 7, 1861) in which he said: “We want no negro equality, no negro citizenship; we want no negro race to degrade our own; and as one man [we] would meet you upon the border with the sword in one hand and the torch in the other.” He returned to Georgia, and with Governor Joseph E. Brown

Joseph E. Brown

Joseph Emerson Brown , often referred to as Joe Brown, was the 42nd Governor of Georgia from 1857 to 1865, and a U.S. Senator from 1880 to 1891...

led the fight for secession against Stephens and Herschel V. Johnson (1812–1880). His influence was a most powerful factor in inducing the "old-line Whigs" to support immediate secession.

.jpg)

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

nation. The selection of Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

as the new nation's chief executive not only dashed Toombs's highest hopes but also turned him into one of the most outspoken critics of the Confederate government and its policies. Nevertheless, Davis chose Toombs as his first Confederate States Secretary of State

Confederate States Secretary of State

The Confederate States Secretary of State was the head of the Confederate States State Department from 1861 to 1865 during the American Civil War. There were three people who served the position in this time. The department crumbled with the Confederate States of America in May 1865, marking the...

. Toombs was the only member of the Davis administration to voice reservations about the attack on Fort Sumter. After reading Lincoln's letter to the governor of South Carolina, Toombs said memorably: "Mr. President, at this time it is suicide, murder, and will lose us every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornet's nest which extends from mountain to ocean, and legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary; it puts us in the wrong; it is fatal." Within months of his appointment, a frustrated Toombs stepped down to join the Confederate States Army

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

. He received a commission as a brigadier general on July 19, 1861, and served first as a brigade commander in the (Confederate) Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac (Confederate)

The Confederate Army of the Potomac, whose name was short-lived, was the command under Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard in the early days of the American Civil War. Its only major combat action was the First Battle of Bull Run. Afterwards, the Army of the Shenandoah was merged into the Army of the...

, and then in David R. Jones's division

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

of the Army of Northern Virginia

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, as well as the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed against the Union Army of the Potomac...

through the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

, Seven Days Battles

Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from...

, Northern Virginia Campaign

Northern Virginia Campaign

The Northern Virginia Campaign, also known as the Second Bull Run Campaign or Second Manassas Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during August and September 1862 in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E...

, and Maryland Campaign

Maryland Campaign

The Maryland Campaign, or the Antietam Campaign is widely considered one of the major turning points of the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North was repulsed by Maj. Gen. George B...

. He was wounded in the hand at the Battle of Antietam

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

. He resigned his CSA commission on March 3, 1863, to become Colonel

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

of the 3rd Cavalry of the Georgia Militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

, and subsequently served as a brigadier general and adjutant and inspector-general of General Gustavus W. Smith

Gustavus Woodson Smith

Gustavus Woodson Smith , more commonly known as G.W. Smith, was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Mexican-American War, a civil engineer, and a major general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.-Early life and Mexico:Smith was born in Georgetown,...

's division of Georgia militia. Denied a military promotion, he resigned his commission and returned home to Washington, Georgia

Washington, Georgia

Washington is a city in Wilkes County, Georgia, United States. The population was 4,295 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Wilkes County...

.

Final years

When the Confederacy finally collapsed in 1865, Toombs barely escaped arrest by Union troops and went into hiding until he fled to CubaCuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

on November 4, and then to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

and Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. He returned to the United States via Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

in 1867. Because he refused to request a pardon from Congress, he never regained his American citizenship. He did restore his lucrative law practice as an "unreconstructed" southerner. In addition, he dominated the Georgia constitutional convention of 1877, where once again he demonstrated the political skill and temperament that earlier had earned him a reputation as one of Georgia's most effective leaders.

Legacy

Georgia's Toombs County is named for Robert Toombs. So is theGeorgia town of Toomsboro, though with a slightly altered spelling. His legacy also lives on in his hometown of Washington, Georgia. Visitors to Washington can tour the Robert Toombs House

Robert Toombs House

Robert Toombs House Historic Site in Washington, Georgia, was the home of Robert Toombs, Confederate general and cabinet member. Operated as a state historic site, the 19th century period historic house museum also features exhibits about the life of Robert Toombs.The house was declared a National...

, a State Historic Site operated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Robert Toombs Christian Academy in Lyons, Georgia

Lyons, Georgia

Lyons is a city in Toombs County, Georgia, United States. The population was 4,169 at the 2000 census. The city is the county seat of Toombs County.Lyons is part of the Vidalia Micropolitan Statistical Area.-Geography:...

was named in his honor.

External links

- Robert Toombs, New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Davis, William C., The Union That Shaped the Confederacy: Robert Toombs and Alexander H. Stephens. University Press of Kansas, 2001. Pp. xi, 284.

Retrieved on 2008-02-13

- The Life of Robert Toombs (Transcription of 1892 text)

- Robert Toombs' Letters to Julia Ann Dubose Toombs, 1850-1867, Digital Library of Georgia