Nuremberg Laws

Encyclopedia

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 were antisemitic laws in Nazi Germany

introduced at the annual Nuremberg Rally

of the Nazi Party. After the takeover of power in 1933

by Hitler, Nazism

became an official ideology incorporating scientific racism

and antisemitism. There was a rapid growth in German legislation directed at Jews, such as the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

which banned "non-Aryans" from the civil-service.

The lack of a clear legal method of defining who was Jewish

had, however, allowed some Jews to escape some forms of discrimination aimed at them. The enactment of laws identifying who was Jewish made it easier for the Nazis to enforce legislation restricting the basic rights of German Jews.

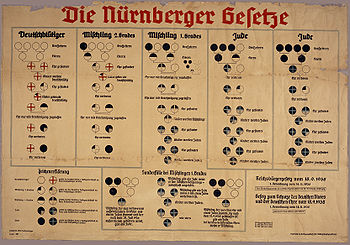

The Nuremberg Laws classified people with four German grandparents as "German or kindred blood", while people were classified as Jews if they descended from three or four Jewish grandparents. A person with one or two Jewish grandparents was a Mischling

, a crossbreed, of "mixed blood". These laws deprived Jews of German citizenship and prohibited marriage between Jews and other Germans.

The Nuremberg Laws also included a ban on sexual intercourse between people defined as "Jews" and non-Jewish Germans and prevented "Jews" from participating in German civic life. These laws were both an attempt to return the Jews of 20th century Germany to the position that Jews had held before their emancipation in the 19th century, although in the 19th century Jews could have evaded restrictions by converting, and this was no longer possible.

The laws were a legal embodiment of an already existing anti-Jewish boycott movement. See Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

.

Before 1806, when general citizenship was largely non-existent in the Holy Roman Empire

Before 1806, when general citizenship was largely non-existent in the Holy Roman Empire

, its inhabitants were subject to different estate

regulations. Varying from one territory of the Empire to another, these regulations classified inhabitants into different groups, such as dynasts, members of the court entourage, other aristocrats, city dwellers (burgher

s), Jews, Huguenot

s (in Prussia a special estate until 1810), free peasant

s, serf

s, peddlers and Gypsies, with different privileges and burdens attached to each classification. Legal inequality was the principle.

The concept of citizenship was mostly restricted to cities, especially free imperial cities

. There was no general franchise, which remained a privilege for the few, who inherited the status or acquired it when they reached a certain level of taxed income or could afford the expensive citizen's fee (Bürgergeld). Citizenship was often further restricted to city dwellers affiliated with the locally dominant Christian denomination (Calvinist, Catholic or Lutheran). City dwellers of other denominations or religions and those who lacked the necessary wealth to qualify as citizens were considered as mere inhabitants who lacked political rights and were sometimes subject to revocable staying permits.

Most Jews then living in German locales that allowed their settlement were automatically defined as mere indigenous inhabitants, depending on permits that were typically less generous than those granted to Gentile indigenous inhabitants. In the 18th c. some Jews and their families (such as Daniel Itzig

in Berlin) gained equal status with their fellow Christian city dwellers, but had a different status than noblemen, Huguenots, or serfs. They often did not enjoy the right to freedom of movement across territorial or even municipal boundaries, let alone enjoy the same status in the new place as in the old.

With the abolition of legal status differences in the Napoleonic era and its aftermath citizenship was established as a new franchise generally applying to all former subjects of the monarchs. While Jewish emancipation did not eliminate all forms of discrimination against Jews, who often remained barred from holding official positions with the State, such forms of discrimination were no longer the guiding principle for ordering society, but a violation of it. These restrictions were mostly abolished in the 1840s, in few smaller states as late as 1869.

In the mid-19th century, the fiercely anti-Semitic völkisch

movement appeared in Germany. One of the major demands of the various völkisch groups had been the disemancipation of German Jews and banning sexual relations between those considered to be of the “Semitic race” and those considered to be of the “Aryan race”. In 1881, a petition presented to the German government by the völkisch groups demanding Jewish disemancipation and the banning of marriage and sexual intercourse between “Aryans” and “Jews” had collected over a million signatures. Reflecting the strength of the völkisch movement, from 1892 when the so-called Tivoli Program was adopted, the Conservative Party

formally advocated disemancipation of German Jews. In his best-selling 1912 book Wenn ich der Kaiser wär (If I were the Kaiser), Heinrich Class

, the leader of one of the more powerful völkisch groups, the Alldeutscher Verband, urged that all German Jews be stripped of their German citizenship and be reduced to Fremdenrecht (alien status). Class went on to urge in Wenn ich der Kaiser wär that Jews be totally excluded from all aspects of German life with Class recommending that Jews be forbidden to own land, hold public office, and to participate in journalism, banking, and the liberal professions.

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), which had been founded in 1919 as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, adopted the movement's demands to disemancipate the Jews as its own. Attacks on Jews started shortly after the Nazi assumption of power

on 30 January 1933, when Adolf Hitler

assumed the Chancellorship. The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

, the first nationwide stage of the anti-Semitic campaign, began on 1 April 1933.

However, the völkisch demand for laws disemancipating Jews and banning sex or marriage between "non-Aryans" and "Aryans" were not immediately met. A dispute between the Interior Ministry and the NSDAP over the precise "racial" definition of a Jew, namely how many Jewish grandparents did one have to have to be considered Jewish, led to the entire process being hopelessly bogged down by 1935.

The lack of a clear definition of who was a Jew confused efforts to enforce anti-Semitic laws and measures. The first Nuremberg law, nominally designed for the "prevention of the propagation of hereditary illness", did not attack Jews explicitly. Other laws claimed to preserve German blood and honour, but again were not specifically anti-Semitic.

During the spring and summer of 1935, many Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters; i.e. those who joined the Nazi Party before 1930, and who tended to be the most ardent anti-Semites in the Party) and SA

members, disenchanted with unfulfilled promises by the Nazi party, were eager to lash out against Germany's Jewish minority as a way of expressing their frustrations against a group that the authorities would not generally protect. The German historian Hans Mommsen

wrote about the Alte Kämpfer that:

report from the spring of 1935 stated that the rank and file of the Nazi Party would set in motion a solution to the "Jewish problem" "by us from below that the government would then have to follow". The ensuing wave of assaults, vandalism and boycotts by the Alte Kämpfer and SA members against German Jews in the spring and summer of 1935 was far more violent then the anti-Semitic campaigns in the two previous years. As a result of this anti-Semitic agitation, these matters were raised to the forefront of the state agenda. The Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka, a leading expert on public opinion in Nazi Germany argued that there was a vast disparity of views between those of the Alte Kämpfer and the general German public, but that even those Germans who were not politically active favored bringing in tougher new anti-Semitic laws in 1935.

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht

, the Economics Minister and Reichsbank president, criticized arbitrary behavior by Party members as this inhibited his policy of developing the German economy

. From Dr. Schacht's viewpoint, the violent anti-Semitic campaign waged by the Alte Kämpfer and SA made no economic sense, since Jews were believed to have certain entrepreneurial skills that could be usefully employed to further his policies. Schacht made no moral condemnation of anti-Jewish policy and advocated the passing of legislation to clarify the situation. Following complaints from Dr. Schacht plus reports on the public disagreement with the wave of anti-Semitic violence, Hitler ordered a stop to "individual actions" against German Jews on 8 August 1935. A conference of ministers was held on 20 August 1935 to discuss the negative economic effects of Party actions against Jews. Hitler argued that such effects would cease once the government decided on a firm policy against the Jews. At the same time, the Interior Minister Dr. Wilhelm Frick

threatened to impose harsh penalties on those Party members who ignored the order of 8 August and continued to assault Jews. From Hitler's perspective, it was imperative to bring in harsh new anti-Semitic laws as a consolation for those Party members who were disappointed with Hitler's order of 8 August, especially because Hitler had only reluctantly given the order for pragmatic reasons, and his sympathies were with the Party radicals.

The seventh Nazi Party Rally

was held in Nuremberg from 10–16 September 1935. It was meant to celebrate the Nazi regime's renunciation of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles

in March 1935, which had disarmed Germany, hence its motto Party Rally of Freedom. The rally saw the Reichstag pass the Reich Flag Law, which was Hitler’s response to the "Bremen

incident" of 26 July 1935 in New York, in which a group of anti-Nazi demonstrators boarded the Bremen, tore the Nazi party flag which the Bremen had been provocatively flying from its jackstaff and tossed it into the Hudson River. When the German Consul protested, U.S. officials responded that the German national flag had not been harmed, only a political party symbol. On 15 September 1935 Hitler declared the Nazi Swastika flag the national flag of Germany.

The Party Rally of September 1935 had featured the first session of the Reichstag held at that city since 1543. Hitler had planned to have the Reichstag pass a law making the Nazi Swastika flag the flag of the German Reich, and a major speech in support of the impending Italian aggression against Ethiopia. However, at the last minute, the German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath

persuaded Hitler to cancel his speech as being too provocative to public opinion abroad as it blatantly contradicted the message of Hitler's "peace speeches", thus leaving Hitler with the sudden need to have something else to address the historic first meeting of the Reichstag in Nuremberg since 1543, other than the Reich Flag Law. Hitler's need for something to present to the Reichstag was especially acute as he had invited all of the senior foreign diplomats in Berlin to the Party Rally of 1935 to hear what was billed as an especially important speech on foreign policy.

On 12 September 1935, two days after the beginning of the party rally, leading Nazi physician Gerhard Wagner surprisingly announced in a speech that the Nazi government would soon introduce a "law for the protection of German blood" to prevent mixed marriages between Jews and "Aryans" in the future. Hitler immediately decided to extend the legal scope. On 13 September, Dr. Bernhard Lösener, the Interior Ministry official in charge of drafting anti-Semitic laws together with another Interior Ministry official, Ministerialrat (Ministerial Counsellor) Franz Albrecht Medicus, was hastily summoned to the Nuremberg Party Rally by plane by Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart

, the State Secretary of the Interior Ministry, and directed to start drafting at once a law for Hitler to present to the Reichstag for 15 September. Lösener and Medicus arrived in Nuremberg on the morning of 14 September.

Because of the short time available for the drafting of the laws, both measures were hastily improvised—there was even a shortage of drafting paper so that menu cards had to be used instead. Such was the degree of improvisation that Franz Gürtner

, the Justice Minister, first learned of the adoption of the laws from listening to the radio. Most of the debates about the drafting of the laws concerned a precise definition of what constituted a Jew in Nazi "racial" terms, i.e. how many Jewish grandparents one had to have in order to qualify as Jewish under Nazi racial theories.

Hitler himself spent the night of 14–15 September hesitant and indecisive over just which of the various definitions of a Jew to adopt, and finally excused himself from the debate. On 15 September, Hitler presented the laws drafted by Stuckart, Lösener and Medicus to the Reichstag.

in Nuremberg, becoming known as the Nuremberg Laws.

The first law, The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, prohibited marriages and extramarital intercourse

between "Jews" (the name was now officially used in place of "non-Aryans") and "Germans" and also the employment of "German" females under forty-five in Jewish households. The second law, The Reich Citizenship Law, declared those not of German blood to be Staatsangehörige (state subjects) while those classified as "Aryans" were Reichsbürger (citizens of the Reich). Between November 1935 to July 1943, 13 implementation ordinances were issued dealing with the enforcement of Reich Citizenship Law that progressively marginalized the Jewish community in Germany.

Hitler appeared before the Reichstag in Nuremberg, introducing the laws and their alleged motivation, before the laws were formally read and proposed for adoption by Hermann Göring

, the President of the Reichstag. In his speech he laid out his case for the new laws:

The measures were unanimously adopted by the Reichstag. In 12 years of Nazi rule, the Reichstag only passed four laws: the Nuremberg laws were two of them.

The Nuremberg Laws formalized the unofficial and particular measures taken against Jews up to 1935. The Nazi leaders made a point of stressing the consistency of this legislation with the Party programme

, which demanded that Jews should be deprived of their citizenship

rights.

The Reich Citizenship Law had little practical effect as it deprived German Jews only of the right to vote and hold office. Much to the fury of the Alte Kämpfer and the other radicals in the NSDAP, the recommendation from the Interior Ministry that the Reich Citizenship Law applied only to those classified as "full Jews" and those "half-Jews" who practiced Judaism or were not in a mixed marriage was taken up; those Mischling who were Christians or were in a mixed marriage retained their German citizenship. The NSDAP had wanted the Reich Citizenship Law to apply to "Grade 1 and Grade 2 persons of mixed descent". The suggestion of Dr. Frick for creation of a tribunal before which every German would have to prove that they were Aryans in order to keep their German citizenship was not followed. Because of this, the Nuremberg Laws were highly unpopular with the Party radicals. Joseph Goebbels

had the radio broadcast recording the passing of the laws by the Reichstag cut short, and ordered the German media not to mention the laws until a way of implementing them had been found. At a secret conference held in Munich on 24 September to finally resolve the dispute over who was a "racial" Jew or who was a "half-Jew", Hitler accepted Lösener's less sweeping definitions of three or four Jewish grandparents, and ruled that the laws were not to apply to those Mischling who were Christians and to "Grade 2 persons of mixed descent". However immediately afterwards in a meeting with Martin Bormann

, Hitler declared that paragraph six of the First Ordinance of the Reich Citizenship was not to be applied in practice, and instead accepted Bormann's suggestion of excluding Mischling from a whole host of German institutions such as the DAF

.

People defined as Jews could then be barred from employment as lawyers, doctors or journalists. Jews were prohibited from using state hospitals and could not be educated by the state past the age of 14. Public parks, libraries and beaches were closed to Jews. War memorials were to have Jewish names expunged. Even the lottery could not award winnings to Jews.

With the so-called Namensänderungsverordnung ("Regulation of Name Changes") of 17 August 1938, Jews with first names of non-Jewish origin were required to adopt a middle name: "Sara" for women and "Israel" for men. At the instigation of Swiss immigration official Heinrich Rothmund, passports of German Jews were required to have a large "J" stamped on them and could be used to leave Germany—but not to return.

The obligation to wear the yellow badge

, introduced in German-occupied Poland in September 1939, was extended to all Jewish people living within the Nazi empire in September 1941.

Later death penalty was applied under Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honour. For example, in a Nuremberg a Jewish businessman Leo Kazenberger was accused of having a sexual relationship with a younger German woman. He was denounced and arrested but he and his alleged girlfriend denied the charges. The case was heard by Oswald Rothaug who, according to many observers, used the case as an opportunity for getting noticed by Hitler. Under wartime law when a crime had been committed during blackout

hours death penalty could be applied. Kazenberger was sentenced to death and guillotined on 2 June 1942.

and derived from a primitive understanding of genetics

. Although the Nazis took these ideas to violent extremes, they were based on thinking that already existed across Europe and America. Nazi laws banning "inter-marriage" assumed that nations were "races" and that the Germans were a Master race

and in accordance with ideas expressed in Eugenics

and Social Darwinism

; they therefore sought to preserve their supposed racial superiority by banning inter-marriage with people they regarded as inferior or as a threat, in particular Jews and Gypsies.

in Bulgaria, in 1940 the ruling Iron Guard

in Romania passed the Law defining the Legal Status of Romanian Jews, in 1941 the Codex Judaicus was enacted in Slovakia and in 1941 the Ustasha in Croatia also passed legislation defining who was a Jew and restricting contact with them. Hungary passed its first "Jewish Law" in May 1938 banning Jews from various professions, further laws emulating the Nuremberg regulations were added in 1941.

, in Eichstätt

, Bavaria, on 27 April 1945. It was appropriated by General George S. Patton

, in violation of JCS 1067. During a visit to Los Angeles, he secretly handed it over to the Huntington Library

. The document was stored until 26 June 1999, when its existence was revealed. Although legal ownership of the document has not been established, it was given on permanent loan to the Skirball Cultural Center

, which placed it on public display three days later, until the document's transfer to the National Archives

in Washington D.C. on 25 August 2010.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

introduced at the annual Nuremberg Rally

Nuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg Rally was the annual rally of the NSDAP in Germany, held from 1923 to 1938. Especially after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, they were large Nazi propaganda events...

of the Nazi Party. After the takeover of power in 1933

Machtergreifung

Machtergreifung is a German word meaning "seizure of power". It is normally used specifically to refer to the Nazi takeover of power in the democratic Weimar Republic on 30 January 1933, the day Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany, turning it into the Nazi German dictatorship.-Term:The...

by Hitler, Nazism

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

became an official ideology incorporating scientific racism

Scientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

and antisemitism. There was a rapid growth in German legislation directed at Jews, such as the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service

The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service , also known as Civil Service Law, Civil Service Restoration Act, and Law to Re-establish the Civil Service, was a law passed by the National Socialist regime on April 7, 1933, two months after Adolf...

which banned "non-Aryans" from the civil-service.

The lack of a clear legal method of defining who was Jewish

Who is a Jew?

"Who is a Jew?" is a basic question about Jewish identity and considerations of Jewish self-identification. The question is based in ideas about Jewish personhood which themselves have cultural, religious, genealogical, and personal dimensions...

had, however, allowed some Jews to escape some forms of discrimination aimed at them. The enactment of laws identifying who was Jewish made it easier for the Nazis to enforce legislation restricting the basic rights of German Jews.

The Nuremberg Laws classified people with four German grandparents as "German or kindred blood", while people were classified as Jews if they descended from three or four Jewish grandparents. A person with one or two Jewish grandparents was a Mischling

Mischling

Mischling was the German term used during the Third Reich to denote persons deemed to have only partial Aryan ancestry. The word has essentially the same origin as mestee in English, mestizo in Spanish and métis in French...

, a crossbreed, of "mixed blood". These laws deprived Jews of German citizenship and prohibited marriage between Jews and other Germans.

The Nuremberg Laws also included a ban on sexual intercourse between people defined as "Jews" and non-Jewish Germans and prevented "Jews" from participating in German civic life. These laws were both an attempt to return the Jews of 20th century Germany to the position that Jews had held before their emancipation in the 19th century, although in the 19th century Jews could have evaded restrictions by converting, and this was no longer possible.

The laws were a legal embodiment of an already existing anti-Jewish boycott movement. See Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany took place on 1 April 1933, soon after Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor on 30 January 1933...

.

Background history

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, its inhabitants were subject to different estate

Estates of the realm

The Estates of the realm were the broad social orders of the hierarchically conceived society, recognized in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period in Christian Europe; they are sometimes distinguished as the three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and commoners, and are often referred to by...

regulations. Varying from one territory of the Empire to another, these regulations classified inhabitants into different groups, such as dynasts, members of the court entourage, other aristocrats, city dwellers (burgher

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

s), Jews, Huguenot

Huguenot

The Huguenots were members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the 17th century, people who formerly would have been called Huguenots have instead simply been called French Protestants, a title suggested by their German co-religionists, the...

s (in Prussia a special estate until 1810), free peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

s, serf

SERF

A spin exchange relaxation-free magnetometer is a type of magnetometer developed at Princeton University in the early 2000s. SERF magnetometers measure magnetic fields by using lasers to detect the interaction between alkali metal atoms in a vapor and the magnetic field.The name for the technique...

s, peddlers and Gypsies, with different privileges and burdens attached to each classification. Legal inequality was the principle.

The concept of citizenship was mostly restricted to cities, especially free imperial cities

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

. There was no general franchise, which remained a privilege for the few, who inherited the status or acquired it when they reached a certain level of taxed income or could afford the expensive citizen's fee (Bürgergeld). Citizenship was often further restricted to city dwellers affiliated with the locally dominant Christian denomination (Calvinist, Catholic or Lutheran). City dwellers of other denominations or religions and those who lacked the necessary wealth to qualify as citizens were considered as mere inhabitants who lacked political rights and were sometimes subject to revocable staying permits.

Most Jews then living in German locales that allowed their settlement were automatically defined as mere indigenous inhabitants, depending on permits that were typically less generous than those granted to Gentile indigenous inhabitants. In the 18th c. some Jews and their families (such as Daniel Itzig

Daniel Itzig

Daniel Itzig was a Court Jew of Kings Frederick II the Great and Frederick William II of Prussia....

in Berlin) gained equal status with their fellow Christian city dwellers, but had a different status than noblemen, Huguenots, or serfs. They often did not enjoy the right to freedom of movement across territorial or even municipal boundaries, let alone enjoy the same status in the new place as in the old.

With the abolition of legal status differences in the Napoleonic era and its aftermath citizenship was established as a new franchise generally applying to all former subjects of the monarchs. While Jewish emancipation did not eliminate all forms of discrimination against Jews, who often remained barred from holding official positions with the State, such forms of discrimination were no longer the guiding principle for ordering society, but a violation of it. These restrictions were mostly abolished in the 1840s, in few smaller states as late as 1869.

In the mid-19th century, the fiercely anti-Semitic völkisch

Völkisch movement

The volkisch movement is the German interpretation of the populist movement, with a romantic focus on folklore and the "organic"...

movement appeared in Germany. One of the major demands of the various völkisch groups had been the disemancipation of German Jews and banning sexual relations between those considered to be of the “Semitic race” and those considered to be of the “Aryan race”. In 1881, a petition presented to the German government by the völkisch groups demanding Jewish disemancipation and the banning of marriage and sexual intercourse between “Aryans” and “Jews” had collected over a million signatures. Reflecting the strength of the völkisch movement, from 1892 when the so-called Tivoli Program was adopted, the Conservative Party

German Conservative Party

The German Conservative Party was a right-wing political party of the German Empire, founded in 1876.- Policies :It was generally seen as representing the interests of the German nobility, the East Elbian Junkers and the Evangelical Church of the Prussian Union, and had its political stronghold...

formally advocated disemancipation of German Jews. In his best-selling 1912 book Wenn ich der Kaiser wär (If I were the Kaiser), Heinrich Class

Heinrich Class

Heinrich Claß was a German right-wing politician and president of the Pan-German League from 1908 to 1939. He is commonly known for his books about far-right policy, written under the pseudonym Daniel Frymann or Einhart...

, the leader of one of the more powerful völkisch groups, the Alldeutscher Verband, urged that all German Jews be stripped of their German citizenship and be reduced to Fremdenrecht (alien status). Class went on to urge in Wenn ich der Kaiser wär that Jews be totally excluded from all aspects of German life with Class recommending that Jews be forbidden to own land, hold public office, and to participate in journalism, banking, and the liberal professions.

Toward the Nuremberg Laws

After the First World War, the Jews of Germany were among the most assimilated in Western Europe, speaking German, as opposed to Yiddish, as their first language. Many were secular or atheistic and many had fought for Germany in the First World War.The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), which had been founded in 1919 as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, adopted the movement's demands to disemancipate the Jews as its own. Attacks on Jews started shortly after the Nazi assumption of power

Machtergreifung

Machtergreifung is a German word meaning "seizure of power". It is normally used specifically to refer to the Nazi takeover of power in the democratic Weimar Republic on 30 January 1933, the day Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany, turning it into the Nazi German dictatorship.-Term:The...

on 30 January 1933, when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

assumed the Chancellorship. The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany took place on 1 April 1933, soon after Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor on 30 January 1933...

, the first nationwide stage of the anti-Semitic campaign, began on 1 April 1933.

However, the völkisch demand for laws disemancipating Jews and banning sex or marriage between "non-Aryans" and "Aryans" were not immediately met. A dispute between the Interior Ministry and the NSDAP over the precise "racial" definition of a Jew, namely how many Jewish grandparents did one have to have to be considered Jewish, led to the entire process being hopelessly bogged down by 1935.

The lack of a clear definition of who was a Jew confused efforts to enforce anti-Semitic laws and measures. The first Nuremberg law, nominally designed for the "prevention of the propagation of hereditary illness", did not attack Jews explicitly. Other laws claimed to preserve German blood and honour, but again were not specifically anti-Semitic.

During the spring and summer of 1935, many Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters; i.e. those who joined the Nazi Party before 1930, and who tended to be the most ardent anti-Semites in the Party) and SA

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

members, disenchanted with unfulfilled promises by the Nazi party, were eager to lash out against Germany's Jewish minority as a way of expressing their frustrations against a group that the authorities would not generally protect. The German historian Hans Mommsen

Hans Mommsen

Hans Mommsen is a left-wing German historian. He is the twin brother of the late Wolfgang Mommsen.-Biography:He was born in Marburg, the son of the historian Wilhelm Mommsen and great-grandson of the Roman historian Theodor Mommsen. He studied German, history and philosophy at the University of...

wrote about the Alte Kämpfer that:

"After the Nazi seizure of power, those groups in the NSDAP that originated in the extreme völkisch movement—including the vast majority of the Alte Kämpfer—did not become socially integrated. Many of them remained unemployed, while others failed to obtain posts commensurate with the services they believed they had rendered the movement. The social advancement that they had hoped for usually failed to materialize. This potential for protest was increasingly diverted into the sphere of Jewish policy. Many extremists in the NSDAP, influenced by envy and greed as well as by a feeling that they had been excluded from attractive positions within the higher civil service, grew even more determined to act decisively and independently in the "Jewish Question". The pressures exerted by the militant wing of the party on the state apparatus were most effective when they were in harmony with the official ideology".A Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

report from the spring of 1935 stated that the rank and file of the Nazi Party would set in motion a solution to the "Jewish problem" "by us from below that the government would then have to follow". The ensuing wave of assaults, vandalism and boycotts by the Alte Kämpfer and SA members against German Jews in the spring and summer of 1935 was far more violent then the anti-Semitic campaigns in the two previous years. As a result of this anti-Semitic agitation, these matters were raised to the forefront of the state agenda. The Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka, a leading expert on public opinion in Nazi Germany argued that there was a vast disparity of views between those of the Alte Kämpfer and the general German public, but that even those Germans who were not politically active favored bringing in tougher new anti-Semitic laws in 1935.

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht

Hjalmar Schacht

Dr. Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht was a German economist, banker, liberal politician, and co-founder of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank under the Weimar Republic...

, the Economics Minister and Reichsbank president, criticized arbitrary behavior by Party members as this inhibited his policy of developing the German economy

Economy of Nazi Germany

World War I and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles with its severe reparations imposed on Germany led to a decade of economic woes, including hyperinflation in the mid 1920s...

. From Dr. Schacht's viewpoint, the violent anti-Semitic campaign waged by the Alte Kämpfer and SA made no economic sense, since Jews were believed to have certain entrepreneurial skills that could be usefully employed to further his policies. Schacht made no moral condemnation of anti-Jewish policy and advocated the passing of legislation to clarify the situation. Following complaints from Dr. Schacht plus reports on the public disagreement with the wave of anti-Semitic violence, Hitler ordered a stop to "individual actions" against German Jews on 8 August 1935. A conference of ministers was held on 20 August 1935 to discuss the negative economic effects of Party actions against Jews. Hitler argued that such effects would cease once the government decided on a firm policy against the Jews. At the same time, the Interior Minister Dr. Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick

Wilhelm Frick was a prominent German Nazi official serving as Minister of the Interior of the Third Reich. After the end of World War II, he was tried for war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials and executed...

threatened to impose harsh penalties on those Party members who ignored the order of 8 August and continued to assault Jews. From Hitler's perspective, it was imperative to bring in harsh new anti-Semitic laws as a consolation for those Party members who were disappointed with Hitler's order of 8 August, especially because Hitler had only reluctantly given the order for pragmatic reasons, and his sympathies were with the Party radicals.

The seventh Nazi Party Rally

Nuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg Rally was the annual rally of the NSDAP in Germany, held from 1923 to 1938. Especially after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, they were large Nazi propaganda events...

was held in Nuremberg from 10–16 September 1935. It was meant to celebrate the Nazi regime's renunciation of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

in March 1935, which had disarmed Germany, hence its motto Party Rally of Freedom. The rally saw the Reichstag pass the Reich Flag Law, which was Hitler’s response to the "Bremen

SS Bremen (1929)

The SS Bremen was a German-built ocean liner constructed for the Norddeutscher Lloyd line to work the transatlantic sea route. The Bremen was notable for her bulbous bow construction, high-speed engines, and low, streamlined profile. At the time of her construction, she and her sister ship were...

incident" of 26 July 1935 in New York, in which a group of anti-Nazi demonstrators boarded the Bremen, tore the Nazi party flag which the Bremen had been provocatively flying from its jackstaff and tossed it into the Hudson River. When the German Consul protested, U.S. officials responded that the German national flag had not been harmed, only a political party symbol. On 15 September 1935 Hitler declared the Nazi Swastika flag the national flag of Germany.

The Party Rally of September 1935 had featured the first session of the Reichstag held at that city since 1543. Hitler had planned to have the Reichstag pass a law making the Nazi Swastika flag the flag of the German Reich, and a major speech in support of the impending Italian aggression against Ethiopia. However, at the last minute, the German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath was a German diplomat remembered mostly for having served as Foreign minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938...

persuaded Hitler to cancel his speech as being too provocative to public opinion abroad as it blatantly contradicted the message of Hitler's "peace speeches", thus leaving Hitler with the sudden need to have something else to address the historic first meeting of the Reichstag in Nuremberg since 1543, other than the Reich Flag Law. Hitler's need for something to present to the Reichstag was especially acute as he had invited all of the senior foreign diplomats in Berlin to the Party Rally of 1935 to hear what was billed as an especially important speech on foreign policy.

On 12 September 1935, two days after the beginning of the party rally, leading Nazi physician Gerhard Wagner surprisingly announced in a speech that the Nazi government would soon introduce a "law for the protection of German blood" to prevent mixed marriages between Jews and "Aryans" in the future. Hitler immediately decided to extend the legal scope. On 13 September, Dr. Bernhard Lösener, the Interior Ministry official in charge of drafting anti-Semitic laws together with another Interior Ministry official, Ministerialrat (Ministerial Counsellor) Franz Albrecht Medicus, was hastily summoned to the Nuremberg Party Rally by plane by Dr. Wilhelm Stuckart

Wilhelm Stuckart

Wilhelm Stuckart was a Nazi Party lawyer and official, a state secretary in the German Interior Ministry and later, a convicted war criminal.-Early life:...

, the State Secretary of the Interior Ministry, and directed to start drafting at once a law for Hitler to present to the Reichstag for 15 September. Lösener and Medicus arrived in Nuremberg on the morning of 14 September.

Because of the short time available for the drafting of the laws, both measures were hastily improvised—there was even a shortage of drafting paper so that menu cards had to be used instead. Such was the degree of improvisation that Franz Gürtner

Franz Gürtner

Franz Gürtner was a German Minister of Justice in Adolf Hitler's cabinet, responsible for coordinating jurisprudence in the Third Reich. Detesting the cruel ways of the Gestapo and SA in dealing with prisoners of war, he protested unsuccessfully to Hitler, nevertheless staying on in the cabinet,...

, the Justice Minister, first learned of the adoption of the laws from listening to the radio. Most of the debates about the drafting of the laws concerned a precise definition of what constituted a Jew in Nazi "racial" terms, i.e. how many Jewish grandparents one had to have in order to qualify as Jewish under Nazi racial theories.

Hitler himself spent the night of 14–15 September hesitant and indecisive over just which of the various definitions of a Jew to adopt, and finally excused himself from the debate. On 15 September, Hitler presented the laws drafted by Stuckart, Lösener and Medicus to the Reichstag.

Introduction of the Laws

On the evening of 15 September 1935, two measures were announced to the Reichstag at the annual Party RallyNuremberg Rally

The Nuremberg Rally was the annual rally of the NSDAP in Germany, held from 1923 to 1938. Especially after Hitler's rise to power in 1933, they were large Nazi propaganda events...

in Nuremberg, becoming known as the Nuremberg Laws.

The first law, The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, prohibited marriages and extramarital intercourse

Rassenschande

Rassenschande or Blutschande was the Nazi term for sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans, which was punishable by law...

between "Jews" (the name was now officially used in place of "non-Aryans") and "Germans" and also the employment of "German" females under forty-five in Jewish households. The second law, The Reich Citizenship Law, declared those not of German blood to be Staatsangehörige (state subjects) while those classified as "Aryans" were Reichsbürger (citizens of the Reich). Between November 1935 to July 1943, 13 implementation ordinances were issued dealing with the enforcement of Reich Citizenship Law that progressively marginalized the Jewish community in Germany.

Hitler appeared before the Reichstag in Nuremberg, introducing the laws and their alleged motivation, before the laws were formally read and proposed for adoption by Hermann Göring

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring, was a German politician, military leader, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. He was a veteran of World War I as an ace fighter pilot, and a recipient of the coveted Pour le Mérite, also known as "The Blue Max"...

, the President of the Reichstag. In his speech he laid out his case for the new laws:

The measures were unanimously adopted by the Reichstag. In 12 years of Nazi rule, the Reichstag only passed four laws: the Nuremberg laws were two of them.

The Nuremberg Laws formalized the unofficial and particular measures taken against Jews up to 1935. The Nazi leaders made a point of stressing the consistency of this legislation with the Party programme

National Socialist Program

The National Socialist Programme , was first, the political program of the German National Socialist Party in 1918, and later, in the 1920s, of the National Socialist German Workers' Party headed by Adolf...

, which demanded that Jews should be deprived of their citizenship

Citizenship

Citizenship is the state of being a citizen of a particular social, political, national, or human resource community. Citizenship status, under social contract theory, carries with it both rights and responsibilities...

rights.

The Laws

The Laws for the Protection of German Blood and German HonourEffect of the Laws

Legal discrimination against Jews had come into being before the Nuremberg Laws and steadily grew as time went on; however, for discrimination to be effective, it was essential to have a clear definition of who was or was not a Jew. This was one important function of the Nuremberg laws and the numerous supplementary decrees that were proclaimed to further them.The Reich Citizenship Law had little practical effect as it deprived German Jews only of the right to vote and hold office. Much to the fury of the Alte Kämpfer and the other radicals in the NSDAP, the recommendation from the Interior Ministry that the Reich Citizenship Law applied only to those classified as "full Jews" and those "half-Jews" who practiced Judaism or were not in a mixed marriage was taken up; those Mischling who were Christians or were in a mixed marriage retained their German citizenship. The NSDAP had wanted the Reich Citizenship Law to apply to "Grade 1 and Grade 2 persons of mixed descent". The suggestion of Dr. Frick for creation of a tribunal before which every German would have to prove that they were Aryans in order to keep their German citizenship was not followed. Because of this, the Nuremberg Laws were highly unpopular with the Party radicals. Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

had the radio broadcast recording the passing of the laws by the Reichstag cut short, and ordered the German media not to mention the laws until a way of implementing them had been found. At a secret conference held in Munich on 24 September to finally resolve the dispute over who was a "racial" Jew or who was a "half-Jew", Hitler accepted Lösener's less sweeping definitions of three or four Jewish grandparents, and ruled that the laws were not to apply to those Mischling who were Christians and to "Grade 2 persons of mixed descent". However immediately afterwards in a meeting with Martin Bormann

Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann was a prominent Nazi official. He became head of the Party Chancellery and private secretary to Adolf Hitler...

, Hitler declared that paragraph six of the First Ordinance of the Reich Citizenship was not to be applied in practice, and instead accepted Bormann's suggestion of excluding Mischling from a whole host of German institutions such as the DAF

German Labour Front

The German Labour Front was the National Socialist trade union organisation which replaced the various trade unions of the Weimar Republic after Adolf Hitler's rise to power....

.

People defined as Jews could then be barred from employment as lawyers, doctors or journalists. Jews were prohibited from using state hospitals and could not be educated by the state past the age of 14. Public parks, libraries and beaches were closed to Jews. War memorials were to have Jewish names expunged. Even the lottery could not award winnings to Jews.

With the so-called Namensänderungsverordnung ("Regulation of Name Changes") of 17 August 1938, Jews with first names of non-Jewish origin were required to adopt a middle name: "Sara" for women and "Israel" for men. At the instigation of Swiss immigration official Heinrich Rothmund, passports of German Jews were required to have a large "J" stamped on them and could be used to leave Germany—but not to return.

The obligation to wear the yellow badge

Yellow badge

The yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

, introduced in German-occupied Poland in September 1939, was extended to all Jewish people living within the Nazi empire in September 1941.

Later death penalty was applied under Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honour. For example, in a Nuremberg a Jewish businessman Leo Kazenberger was accused of having a sexual relationship with a younger German woman. He was denounced and arrested but he and his alleged girlfriend denied the charges. The case was heard by Oswald Rothaug who, according to many observers, used the case as an opportunity for getting noticed by Hitler. Under wartime law when a crime had been committed during blackout

Blackout (wartime)

A blackout during war, or apprehended war, is the practice of collectively minimizing outdoor light, including upwardly directed light. This was done in the 20th century to prevent crews of enemy aircraft from being able to navigate to their targets simply by sight, for example during the London...

hours death penalty could be applied. Kazenberger was sentenced to death and guillotined on 2 June 1942.

Nazi Eugenics and Racial belief

The Nuremberg laws were based on a belief in Scientific racismScientific racism

Scientific racism is the use of scientific techniques and hypotheses to sanction the belief in racial superiority or racism.This is not the same as using scientific findings and the scientific method to investigate differences among the humans and argue that there are races...

and derived from a primitive understanding of genetics

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

. Although the Nazis took these ideas to violent extremes, they were based on thinking that already existed across Europe and America. Nazi laws banning "inter-marriage" assumed that nations were "races" and that the Germans were a Master race

Master race

Master race was a phrase and concept originating in the slave-holding Southern US. The later phrase Herrenvolk , interpreted as 'master race', was a concept in Nazi ideology in which the Nordic peoples, one of the branches of what in the late-19th and early-20th century was called the Aryan race,...

and in accordance with ideas expressed in Eugenics

Eugenics

Eugenics is the "applied science or the bio-social movement which advocates the use of practices aimed at improving the genetic composition of a population", usually referring to human populations. The origins of the concept of eugenics began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance,...

and Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is a term commonly used for theories of society that emerged in England and the United States in the 1870s, seeking to apply the principles of Darwinian evolution to sociology and politics...

; they therefore sought to preserve their supposed racial superiority by banning inter-marriage with people they regarded as inferior or as a threat, in particular Jews and Gypsies.

Impact of the Laws outside Germany

Allies of the Nazis passed their own versions of the Nuremberg laws including The Law for Protection of the NationLaw for protection of the nation

The Law for protection of the nation was a Bulgarian law, effective from 23 January 1941 to 27 November 1944, which directed measures against Jews and others...

in Bulgaria, in 1940 the ruling Iron Guard

Iron Guard

The Iron Guard is the name most commonly given to a far-right movement and political party in Romania in the period from 1927 into the early part of World War II. The Iron Guard was ultra-nationalist, fascist, anti-communist, and promoted the Orthodox Christian faith...

in Romania passed the Law defining the Legal Status of Romanian Jews, in 1941 the Codex Judaicus was enacted in Slovakia and in 1941 the Ustasha in Croatia also passed legislation defining who was a Jew and restricting contact with them. Hungary passed its first "Jewish Law" in May 1938 banning Jews from various professions, further laws emulating the Nuremberg regulations were added in 1941.

Existing copies

An original typescript of the laws signed by Hitler was found by the 203rd Detachment of the U.S. Army's Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC), commanded by Martin DannenbergMartin Dannenberg

Martin Ernest Dannenberg was an American insurance executive. He served as chairman of the Sun Life Insurance Company for five decades. While serving as a counterintelligence officer in the United States Army during World War II with the U.S. Third Army, Dannenberg discovered an original copy of...

, in Eichstätt

Eichstätt

Eichstätt is a town in the federal state of Bavaria, Germany, and capital of the District of Eichstätt. It is located along the Altmühl River, at , and had a population of 13,078 in 2002. It is home to the Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, the lone Catholic university in Germany. The...

, Bavaria, on 27 April 1945. It was appropriated by General George S. Patton

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton, Jr. was a United States Army officer best known for his leadership while commanding corps and armies as a general during World War II. He was also well known for his eccentricity and controversial outspokenness.Patton was commissioned in the U.S. Army after his graduation from...

, in violation of JCS 1067. During a visit to Los Angeles, he secretly handed it over to the Huntington Library

The Huntington Library

The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens is an educational and research institution established by Henry E. Huntington in San Marino, in the San Rafael Hills near Pasadena, California in the United States...

. The document was stored until 26 June 1999, when its existence was revealed. Although legal ownership of the document has not been established, it was given on permanent loan to the Skirball Cultural Center

Skirball Cultural Center

The Skirball Cultural Center is an educational institution in Los Angeles, California devoted to sustaining Jewish heritage and American democratic ideals. Open to the public since 1996, the Skirball Cultural Center is dedicated to exploring the connections between 4,000 years of Jewish heritage...

, which placed it on public display three days later, until the document's transfer to the National Archives

National Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration is an independent agency of the United States government charged with preserving and documenting government and historical records and with increasing public access to those documents, which comprise the National Archives...

in Washington D.C. on 25 August 2010.

See also

- Hans GlobkeHans Globke- See also :* Theodor Oberländer* Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff- Bibliography :* Tetens, T.H. The New Germany and the Old Nazis. Random House/Marzani & Munsel, New York, 1961. LCN 61-7240....

- Nazism and raceNazism and raceNazism developed several theories concerning races. The Nazis claimed to scientifically measure a strict hierarchy of human race; at the top was the master race, the "Aryan race", narrowly defined by the Nazis as being identical with the Nordic race, followed by lesser races.At the bottom of this...

- Aryan paragraphAryan paragraphAn Aryan paragraph is a clause in the statutes of an organization, corporation, or real estate deed that reserves membership and/or right of residence solely for members of the Aryan race and excludes from such rights any non-Aryans, particularly Jews or those of Jewish descent, as well as to those...

- Manifesto of Race in Italy

- Jim Crow LawsJim Crow lawsThe Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

- Apartheid

- Reichstag Fire DecreeReichstag Fire DecreeThe Reichstag Fire Decree is the common name of the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State issued by German President Paul von Hindenburg in direct response to the Reichstag fire of 27 February 1933. The decree nullified many of the key civil liberties of German...

- Visigothic CodeVisigothic CodeThe Visigothic Code comprises a set of laws promulgated by the Visigothic king of Hispania, Chindasuinth in his second year...

Further reading

- Banker, David "The 'Jewish Question' as a Focus of Conflict Between Trends of Institutionalization and Radicalization in the Third Reich, 1934–1935" pages 357–371 from In Nation and History: Studies in the History of the Jewish People; Based on the Papers Delivered at the Eight World Congress of Jewish Studies, Volume 2 edited by Samuel Ettinger, Jerusalem, 1984.

- Bankier, David "Nuremberg Laws" pages 1076–1077 from the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust Volume 3 edited by Israel GutmanIsrael GutmanIsrael Gutman is a Polish-born Israeli historian of the Holocaust.Israel Gutman was born in Warsaw, Poland. After playing an important role in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, he was deported to the Majdanek, Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps. His older sister died in the ghetto. After...

, New York: Macmillan, 1990, ISBN 0-02-864527-8. - Ehrenreich, Eric. The Nazi Ancestral Proof: Genealogy, Racial Science, and the Final Solution. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-253-34945-3

- Gruchmann, L. "'Blutschutzgestz' und Justiz: Zur Entstehung und Auswirkung des Nürnberger Gesetzes von 15 September 1935" pages 418–442 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 31, 1983.

- Kulka, Otto Dov "Die Nürnberger Rassengesetze und die deutsche Bevölkerugn um Lichte geheimer NS-Lage und Stimmungsberichte" pages 582–624 from Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, Volume 32, 1984.

- Margaliot, A. "The Reaction of the Jewish Public in Germany to the Nuremberg Laws" pages 193–229 from Vad Yashem Studies, Volume 12, 1977.

- Mommsen, Hans "The Realization of the Unthinkable: The "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" in the Third Reich" pages 217–264 from The Nazi Holocaust Part 3 The "Final Solution": The Implementation of Mass Murder Volume 1 edited by Michael MarrusMichael MarrusMichael Robert Marrus is a Canadian historian of France, the Holocaust and Jewish history. He was born in Toronto and received his BA at the University of Toronto in 1963 and his MA and PhD at the University of California, Berkeley in 1964 and 1968...

, Westpoint: Meckler, 1989, ISBN 0887362664. - Schleunes, Karl The Twisted Road to Auschwitz: Nazi Policy towards German Jews, 1933–1939, Urbana, Ill, 1970.

External links

- Rise of the Nazis and Beginning of Persecution on the Yad VashemYad VashemYad Vashem is Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, established in 1953 through the Yad Vashem Law passed by the Knesset, Israel's parliament....

website - The Citizenship Law, together with Supplementary Decree of 14 November 1935

- The Citizenship Law, English translation at the University of the West of England

- The Blood Law, English translation at the University of the West of England

- Race Laws (Nazi and other)

- Info from Holocaust Museum

- Nazi Race Laws to 1939

- Images of a 1938 German "J" Jewish passport from www.passportland.com