Ninian Edwards

Encyclopedia

Ninian Edwards was a founding political figure of the state of Illinois

. He served as the first and only governor of the Illinois Territory

from 1809 to 1818, as one of the first two United States Senators from Illinois from 1818 to 1824, and as the third Governor of Illinois

from 1826 to 1830. In a time and place where personal coalitions were more influential than parties, Edwards led one of the two main factions in frontier Illinois politics.

Born in Maryland

, Edwards began his political career in Kentucky

, where he served as a legislator and judge. He rose to the position of Chief Justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

in 1808, at the time Kentucky's highest court. In 1809, U.S. President James Madison

appointed him to govern the newly created Illinois Territory. He held that post for three terms, overseeing the territory's transition first to democratic "second grade" government, and then to statehood in 1818. On its second day in session, the Illinois General Assembly

elected Edwards to the U.S. Senate, where conflict with rivals damaged him politically.

Edwards won an unlikely 1826 election to become Governor of Illinois. Conflict with the legislature over state bank regulations marked Edwards' administration, as did the pursuit of Indian removal

. As governor or territorial governor he twice sent Illinois militia against Native Americans, in the War of 1812 and the Winnebago War

, and signed treaties for the cession of Native American land. Edwards returned to private life when his term ended in 1830 and died of cholera

two years later.

in Montgomery County, Maryland

. His mother, Margaret Beall Edwards, was from another prominent local family. His father Benjamin Edwards

served in the Maryland House of Delegates

, in Maryland's state ratifying convention for the U.S. Constitution, and in the United States House of Representatives

, filling a vacant seat for two months.. Ninian was educated by private tutors, one of whom was the future U.S. Attorney General William Wirt

. He attended Dickinson College

from 1790 to 1792 but did not graduate, leaving college to study law. His son Ninian W. Edwards wrote later that Edwards spent some of his time at Dickinson reading medicine, a field to which he devoted considerable time in his later years.

In 1794, at the age of 19, Edwards moved to Nelson County, Kentucky

to manage some family land. He showed a great aptitude for business and leadership and was soon elected to a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives

, before he was even eligible to vote. In 1802 he was awarded the rank of major in the militia. In 1803 he moved to Russellville, Kentucky

, and won a succession of public offices: circuit court judge

in 1803, presidential elector in 1804 (voting for Thomas Jefferson

), and judge and finally chief justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

, which at the time was Kentucky's highest court. He joined the high court in 1806 and won the leadership position in 1808.

A well-educated landowning aristocrat, Edwards deliberately cultivated the image of the natural leader. Thomas Ford

writes that he continued to dress like an 18th-century gentleman long after such fashions had gone out of style, and that his public speaking was marked by showy eloquence. Edwards consciously positioned himself in the select class of men who dominated Kentucky and, later, Illinois politics. In 1803 in Russellville, Edwards married Elvira Lane, a relative from Maryland.

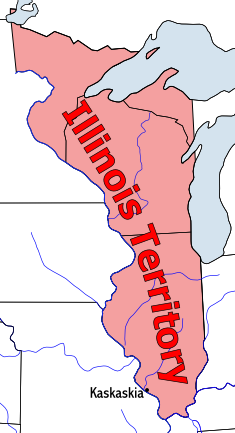

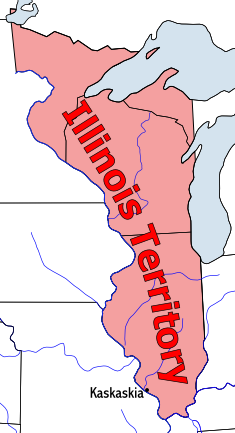

The Illinois Territory was created in 1809. It included all of what today is the state of Wisconsin

The Illinois Territory was created in 1809. It included all of what today is the state of Wisconsin

, as well as parts of Minnesota

and Michigan

. Its population was almost entirely concentrated in the south, in the region later known as Egypt

. President James Madison

first appointed Kentucky politician John Boyle

as its governor. Boyle collected his salary for the position for 21 days but then resigned to take Edwards' job as Kentucky Chief Justice, while friends in Washington helped secure Edwards' appointment as territorial governor. In the meantime, Territorial Secretary Nathaniel Pope

, a cousin of Edwards, had to assume the powers of acting governor, creating Illinois' first counties and appointing officials to form the new government. Only 34 years old at the time of his appointment, Ninian Edwards is the youngest man ever to govern Illinois as either a state or a territory.

Edwards settled in the American Bottom

on land he received as a grant upon his appointment as governor. He named his new farm Elvirade, after his wife. Along with his family, Edwards brought a number of slaves, whom he did not free even though the Northwest Ordinance

of 1787 had made slavery illegal in the territory. An 1803 "Law Concerning Servants" had been promulgated for the Indiana Territory

by then-Governor William Henry Harrison

that maintained the status of people brought into the territory "under contract to serve another in any trade or occupation". The law, which remained in force in the Illinois territory, permitted slavery to persist for decades under the guise of indentured servitude

. Most of Illinois' early governors were slaveowners, and Edwards was no exception. Later, he may have made extra income by renting some of his "indentured servants" out for labor in Missouri.

The new territorial governor was sworn in on June 11, 1809. At first Edwards tried to avoid partisanship but soon found that faction was an inevitable result of his power to appoint officials and distribute government jobs. Although the First Party System

continued to define national politics, the Federalist and Republican Parties never took hold in frontier Illinois. Rather, factional loyalties were created by personality, personal bonds such as kinship and militia service, and especially the distribution of patronage

. In the early territorial years, two rival factions grew up around Edwards and Judge Jesse B. Thomas

. These two factions formed Illinois' political landscape during its time as a territory and for its first several years of statehood.

in the Illinois Territory. Before 1812, while Illinois had a first-grade territorial status, Edwards had vast powers to appoint county and local officials; however, he made it his practice to consider local opinion as much as he could when making appointments, often giving weight to petitions signed by local residents. He attempted to do the same for militia officers for a time, letting the men of a unit elect their leaders, but he soon abandoned this policy as impractical.

In 1812, Edwards successfully persuaded Congress to modify a provision of the 1787 Ordinance limiting voting rights to freeholders of 50 acres (20.2 ha) of land. Due to long-running disputes over fraudulently sold lands, very few Illinois frontiersmen could qualify. At Edwards' urging, Congress granted the Illinois Territory universal white male suffrage

, making it the most democratic U.S. territory at the time. In April, Edwards held a referendum on moving to second-grade government, allowing the people of Illinois to elect a legislature and a non-voting delegate to Congress. The referendum passed, and elections were held in October that sent Shadrach Bond

to Washington as Illinois' first congressional delegate.

. Relations between Illinois settlers and Native Americans worsened throughout the territory during 1810 and 1811. By June 1811, Governor Edwards ordered the construction of a series of blockhouses and called out three companies of militia.

The declaration of war and the Battle of Fort Dearborn in 1812 convinced Edwards that Potawatomi

and Kickapoo

in the territory were preparing to launch a major attack on the southern settlements. In his capacity as commander in chief, Edwards gathered 350 mounted rangers and volunteers near Edwardsville

and personally led an expedition north to Peoria

. After burning two Kickapoo villages on the Sangamon River

along the way, the militia advanced on Peoria itself. All told, the short campaign burned several villages and inflicted dozens of casualties before returning. The attack angered both the Peoria villagers and the U.S. government because it had been carried out against Native Americans loyal to Black Partridge

and Gomo

, two leaders who had not joined Tecumseh's War

and were considered friendly to U.S. interests. A second attack under Captain Thomas Craig killed a large number of French settlers from Peoria as well as Potawatomi. In 1813, Illinois and Missouri militia joined a force of United States infantry under Benjamin Howard

to drive all Native American villagers away from Peoria and establish Fort Clark.

Edwards' actions alienated those Native Americans friendly to the U.S. in the region. Ninian Edwards, having lost the confidence of the Madison administration, waited out the war in Kentucky. However, he was reappointed to a second and then a third term as territorial governor in 1812 and 1815, and he was also named one of the three U.S. negotiators of the Treaties of Portage des Sioux

in 1815.

, and investment in sawmills, grist mills, and stores.

Edwards' political rivalry with Jesse B. Thomas continued for the rest of his time as governor. Edwards, along with much of the legislature, criticized the territory's judges for their inactivity. Among their complaints were that the judges did not hold court often enough and spent too much time absent from the territory. The legislature passed a bill in 1814 to reform the territory's judicial system. The judges refused to acknowledge the act, claiming that they were outside the jurisdiction of the legislature. In 1815 the issue was resolved by Congress, which passed a law supporting Edwards and the legislature.

In December 1817, Edwards, responding to a movement for statehood led by his ally Daniel Pope Cook

, recommended to the legislature that Illinois apply for admission to the Union. He also recommended that a census first be taken of the territory, a standard practice, but the legislature rejected this. Legislators, particularly those opposed to slavery, feared that any delay would allow Missouri

to apply for statehood before Illinois, and that since Missouri was a slave state, this would cause so much turmoil in Congress that it would delay Illinois' admission even longer.

In order to emphasize to Congress that Illinois would be a free state, the legislature passed in January 1818 a bill that would both abolish Illinois' "indentured servant" system of de facto slavery, and prohibit Illinois' future Constitution from reinstating it. Governor Edwards issued his only veto to send the bill back to the legislature, and it was never revised. He made his objections on constitutional grounds, but he also had a conflict of interest as the owner of several slaves himself.

During Edwards' terms as territorial governor, Illinois' population more than tripled, from 12,282 in 1810 to 40,258 in 1818 (a census was finally conducted later that year). The population did not meet the 60,000 threshold the Northwest Ordinance required for a new state, but both Illinoisans and Congress expected continued growth.

met in Kaskaskia. On October 6, Ninian Edwards stepped down, and Shadrach Bond was inaugurated as Illinois' first governor. The following day the new state legislature voted for Illinois' two members of the U.S. Senate. Edwards was quickly chosen on the first ballot; his rival Thomas was only elected after the fourth. Edwards and Thomas then drew straws to determine their respective terms: Thomas was placed in Class II of the Senate

and could serve until 1823, while Edwards was placed in Class III and had to face reelection in February 1819. Edwards and Thomas still had to wait for Congress to formally ratify Illinois' constitution and admission to the Union, which it did on November 25. On December 3 the two Senators were finally seated, leaving Edwards with a mere three months in his first term.

Edwards' re-election was more difficult. In four months he had lost the temporary support of Thomas' allies in the General Assembly who had voted for him in 1818. He narrowly defeated Thomas partisan Michael Jones by a vote of 23–19. This may have been due to the influence of the powerful Secretary of State Elias Kane

, a Thomas ally.

Like most members of Congress during the Era of Good Feelings

, Senator Edwards sat as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party. As his second term drew on, he joined the Adams

-Clay

faction that would develop into the National Republicans after Edwards left office. Edwards voted for the Missouri Compromise

in 1820, a bill that Thomas sponsored. He voted against a law reducing prices for federal land, which made both Edwards and Representative Daniel Pope Cook

targets of criticism at home. On May 6, 1821, Cook married Edwards' daughter Julia.

Ninian Edwards caused trouble for himself when he wrote several articles in the Washington Republican under the pseudonym "A.B." that attacked U.S. Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford

. Edwards alleged that Crawford had known of the impending failure of Illinois' Bank of Edwardsville in 1821, but had not withdrawn federal money from it. Edwards found that none of Crawford's rivals were willing to support his charges, and he was unable to produce corroborating evidence. He resigned his Senate seat on March 4, 1824, to take a job he wanted as the USA's first Minister to Mexico

. While en route to his new position, Edwards was called back to Washington to testify before a special House committee concerning the "A.B. Plot". Unable to substantiate his claims, Edwards resigned his diplomatic post, to be replaced by Joel Roberts Poinsett

.

Back in Illinois, Edwards settled in Belleville

, a town whose site he had once owned before selling off its lots at a profit.

were becoming a force in Illinois politics. Illinois frontier voters so admired Jackson that soon, for the first time, they would give their support to a national party, the Democrats

. Ninian Edwards never criticized Jackson, but as an Adams-Clay Republican Senator he was not part of Jackson's growing coalition. Jacksonians deeply resented Edwards' ally Cook, who had voted against Jackson when the presidential election of 1824

was decided in the House of Representatives.

However, when he ran for governor in 1826, Edwards had the good fortune to enter a three-way race that split the Jacksonians between state Senator Thomas Sloo and Lieutenant Governor Adolphus Hubbard. As a campaign issue, Edwards focused on Illinois' dire financial situation, blaming Sloo and Hubbard and other legislators for it. Edwards won 49.5 percent of the vote to Sloo's 46 percent, with the rest going to Hubbard.

Edwards' administration was hampered by his conflict with the legislature, primarily over the struggling Bank of Illinois. The bank had been established in 1821, and from the beginning it had been underfunded, its notes had badly depreciated, and it had helped put the state deeply in debt. In his inaugural address Edwards undiplomatically attacked bank officials and politicians alike, accusing them of fraud and perjury. From that point, Edwards had a poor relationship with the General Assembly. During his term the Assembly did eventually pass a bank regulation bill, but it also passed a measure to relieve debtors despite Edwards' objections that the state could not afford it.

In 1827 Illinois established its first penitentiary, at Alton

. That same year, the state received a federal land grant to build the Illinois and Michigan Canal

, though work did not begin for several years.

Also in 1827, Edwards ordered the Illinois militia to join another war against Native Americans in northern Illinois. The Winnebago War

, fought between white settlers and members of the Ho-Chunk

tribe, broke out in Wisconsin (then part of the Michigan Territory

) but spread to the lead-mining region around Galena

. Edwards dispatched the militia and ordered 600 more men to be recruited in Sangamon County

. The show of force convinced the Ho-Chunk to surrender.

After the war, Edwards urged the federal government to remove

the remaining Native Americans from northern Illinois, claiming that their presence violated "the rights of a sovereign and independent state", and hinting that he might dispatch the militia again to force them out. The federal government applied diplomatic pressure, and on July 29, 1829, the Potawatomi, Ottowa, and Ojibwe ceded 3000 square miles (7,770 km²) of northern land to the State of Illinois; the Winnebago made a cession in August.

epidemic came through the area in 1833, carried by Winfield Scott

's troops during the Black Hawk War

. Edwards stayed in the town to care for his patients and caught the disease, dying on July 20. Ninian Edwards was interred in Belleville, but he was later moved to Springfield

's Oak Ridge Cemetery

.

, in the General Assembly, and as Illinois' first Superintendent of Public Instruction. He was married to Elizabeth Porter Todd, a sister of Mary Todd Lincoln

. Their daughter Julia Cook Edwards married Edward Lewis Baker, editor of the Illinois State Journal and son of Congressman David Jewett Baker.

Another son, Albert Gallatin Edwards

(1812–1892), was an assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury under U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

. In 1887 he founded the brokerage firm A. G. Edwards in Saint Louis, Missouri. A third son, Benjamin S. Edwards

(1818–1886), established a successful law practice in Springfield, Illinois

and served as a judge in Illinois' Thirteenth Circuit. Ninian Edwards' daughter, Julia Edwards Cook, married Congressman Daniel Pope Cook

. Their son, John Cook, was a mayor of Springfield and a general in the Union Army

during the American Civil War

.

was named for him, as is the St. Louis, Missouri

Metro-East

area city of Edwardsville, Illinois

. Both were named for him during his time as territorial governor. The territorial legislature named Edwards County, while Edwardsville was named by its founder, Thomas Kirkpatrick.

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

. He served as the first and only governor of the Illinois Territory

Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. The area was earlier known as "Illinois Country" while under...

from 1809 to 1818, as one of the first two United States Senators from Illinois from 1818 to 1824, and as the third Governor of Illinois

Governor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

from 1826 to 1830. In a time and place where personal coalitions were more influential than parties, Edwards led one of the two main factions in frontier Illinois politics.

Born in Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, Edwards began his political career in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, where he served as a legislator and judge. He rose to the position of Chief Justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky....

in 1808, at the time Kentucky's highest court. In 1809, U.S. President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

appointed him to govern the newly created Illinois Territory. He held that post for three terms, overseeing the territory's transition first to democratic "second grade" government, and then to statehood in 1818. On its second day in session, the Illinois General Assembly

Illinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois and comprises the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Illinois has 59 legislative districts, with two...

elected Edwards to the U.S. Senate, where conflict with rivals damaged him politically.

Edwards won an unlikely 1826 election to become Governor of Illinois. Conflict with the legislature over state bank regulations marked Edwards' administration, as did the pursuit of Indian removal

Indian Removal

Indian removal was a nineteenth century policy of the government of the United States to relocate Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river...

. As governor or territorial governor he twice sent Illinois militia against Native Americans, in the War of 1812 and the Winnebago War

Winnebago War

The Winnebago War was a brief conflict that took place in 1827 in the Upper Mississippi River region of the United States, primarily in what is now the state of Wisconsin. Not quite a war, the hostilities were limited to a few attacks on American civilians by a portion of the Winnebago Native...

, and signed treaties for the cession of Native American land. Edwards returned to private life when his term ended in 1830 and died of cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

two years later.

Early life

Ninian Edwards was born in 1775 to the prominent Edwards familyEdwards-Lincoln-Porter family

The Edwards-Lincoln-Porter family is a family of politicians from the United States. Below is a list of members:* Benjamin Edwards , Maryland 1782-1784, Maryland State Court Judge 1793, U.S. Representative from Maryland 1795...

in Montgomery County, Maryland

Montgomery County, Maryland

Montgomery County is a county in the U.S. state of Maryland, situated just to the north of Washington, D.C., and southwest of the city of Baltimore. It is one of the most affluent counties in the United States, and has the highest percentage of residents over 25 years of age who hold post-graduate...

. His mother, Margaret Beall Edwards, was from another prominent local family. His father Benjamin Edwards

Benjamin Edwards (Maryland)

Benjamin Edwards was an American merchant and political leader from Montgomery County, Maryland. He represented the third district of Maryland for a very short time in the United States House of Representatives in 1795 after Uriah Forrest resigned.Benjamin's son, Ninian Edwards, would later serve...

served in the Maryland House of Delegates

Maryland House of Delegates

The Maryland House of Delegates is the lower house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland, and is composed of 141 Delegates elected from 47 districts. The House chamber is located in the state capitol building on State Circle in Annapolis...

, in Maryland's state ratifying convention for the U.S. Constitution, and in the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

, filling a vacant seat for two months.. Ninian was educated by private tutors, one of whom was the future U.S. Attorney General William Wirt

William Wirt

William Wirt may refer to:* William Wirt * William Wirt...

. He attended Dickinson College

Dickinson College

Dickinson College is a private, residential liberal arts college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Originally established as a Grammar School in 1773, Dickinson was chartered September 9, 1783, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, making it the first college to be founded in the newly...

from 1790 to 1792 but did not graduate, leaving college to study law. His son Ninian W. Edwards wrote later that Edwards spent some of his time at Dickinson reading medicine, a field to which he devoted considerable time in his later years.

In 1794, at the age of 19, Edwards moved to Nelson County, Kentucky

Nelson County, Kentucky

Nelson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2010, the population was 43,437. Its county seat is Bardstown. The county is part of the Louisville/Jefferson County, KY–IN Metropolitan Statistical Area.- History :...

to manage some family land. He showed a great aptitude for business and leadership and was soon elected to a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

, before he was even eligible to vote. In 1802 he was awarded the rank of major in the militia. In 1803 he moved to Russellville, Kentucky

Russellville, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 7,149 people, 3,064 households, and 1,973 families residing in the city. The population density was 672.1 people per square mile . There were 3,458 housing units at an average density of 325.1 per square mile...

, and won a succession of public offices: circuit court judge

Kentucky Circuit Courts

The Kentucky Circuit Courts are the state courts of general jurisdiction in the U.S. state of Kentucky.The Circuit Courts are trial courts with original jurisdiction in cases involving capital offenses, felonies, land disputes, contested probates of wills, and civil lawsuits in disputes with an...

in 1803, presidential elector in 1804 (voting for Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

), and judge and finally chief justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals

Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky....

, which at the time was Kentucky's highest court. He joined the high court in 1806 and won the leadership position in 1808.

A well-educated landowning aristocrat, Edwards deliberately cultivated the image of the natural leader. Thomas Ford

Thomas Ford (politician)

Thomas Ford was the eighth Governor of Illinois, and served in this capacity from 1842 to 1846. A Democrat, he is remembered largely for his involvement in the death of Joseph Smith, Jr., and the subsequent Illinois Mormon War...

writes that he continued to dress like an 18th-century gentleman long after such fashions had gone out of style, and that his public speaking was marked by showy eloquence. Edwards consciously positioned himself in the select class of men who dominated Kentucky and, later, Illinois politics. In 1803 in Russellville, Edwards married Elvira Lane, a relative from Maryland.

Territorial governorship

Wisconsin

Wisconsin is a U.S. state located in the north-central United States and is part of the Midwest. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake Michigan to the east, Michigan to the northeast, and Lake Superior to the north. Wisconsin's capital is...

, as well as parts of Minnesota

Minnesota

Minnesota is a U.S. state located in the Midwestern United States. The twelfth largest state of the U.S., it is the twenty-first most populous, with 5.3 million residents. Minnesota was carved out of the eastern half of the Minnesota Territory and admitted to the Union as the thirty-second state...

and Michigan

Michigan

Michigan is a U.S. state located in the Great Lakes Region of the United States of America. The name Michigan is the French form of the Ojibwa word mishigamaa, meaning "large water" or "large lake"....

. Its population was almost entirely concentrated in the south, in the region later known as Egypt

Little Egypt (region)

-Early history:The earliest inhabitants of Illinois were thought to have arrived about 12,000 B.C. They were hunter-gatherers, but developed a primitive system of agriculture. After 1000 AD, their agricultural surpluses enabled them to develop complex, hierarchical societies...

. President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

first appointed Kentucky politician John Boyle

John Boyle (congressman)

John Boyle was a United States federal judge and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives....

as its governor. Boyle collected his salary for the position for 21 days but then resigned to take Edwards' job as Kentucky Chief Justice, while friends in Washington helped secure Edwards' appointment as territorial governor. In the meantime, Territorial Secretary Nathaniel Pope

Nathaniel Pope

Nathaniel Pope was a politician and jurist from the U.S. state of Illinois.-Early life, education, and career:...

, a cousin of Edwards, had to assume the powers of acting governor, creating Illinois' first counties and appointing officials to form the new government. Only 34 years old at the time of his appointment, Ninian Edwards is the youngest man ever to govern Illinois as either a state or a territory.

Edwards settled in the American Bottom

American Bottom

The American Bottom is the flood plain of the Mississippi River in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois, extending from Alton, Illinois, to the Kaskaskia River. It is also sometimes called "American Bottoms". The area is about , mostly protected from flooding by a levee and drainage canal...

on land he received as a grant upon his appointment as governor. He named his new farm Elvirade, after his wife. Along with his family, Edwards brought a number of slaves, whom he did not free even though the Northwest Ordinance

Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance was an act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States, passed July 13, 1787...

of 1787 had made slavery illegal in the territory. An 1803 "Law Concerning Servants" had been promulgated for the Indiana Territory

Indiana Territory

The Territory of Indiana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1800, until November 7, 1816, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Indiana....

by then-Governor William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison was the ninth President of the United States , an American military officer and politician, and the first president to die in office. He was 68 years, 23 days old when elected, the oldest president elected until Ronald Reagan in 1980, and last President to be born before the...

that maintained the status of people brought into the territory "under contract to serve another in any trade or occupation". The law, which remained in force in the Illinois territory, permitted slavery to persist for decades under the guise of indentured servitude

Indentured servant

Indentured servitude refers to the historical practice of contracting to work for a fixed period of time, typically three to seven years, in exchange for transportation, food, clothing, lodging and other necessities during the term of indenture. Usually the father made the arrangements and signed...

. Most of Illinois' early governors were slaveowners, and Edwards was no exception. Later, he may have made extra income by renting some of his "indentured servants" out for labor in Missouri.

The new territorial governor was sworn in on June 11, 1809. At first Edwards tried to avoid partisanship but soon found that faction was an inevitable result of his power to appoint officials and distribute government jobs. Although the First Party System

First Party System

The First Party System is a model of American politics used by political scientists and historians to periodize the political party system existing in the United States between roughly 1792 and 1824. It featured two national parties competing for control of the presidency, Congress, and the states:...

continued to define national politics, the Federalist and Republican Parties never took hold in frontier Illinois. Rather, factional loyalties were created by personality, personal bonds such as kinship and militia service, and especially the distribution of patronage

Patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows to another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings or popes have provided to musicians, painters, and sculptors...

. In the early territorial years, two rival factions grew up around Edwards and Judge Jesse B. Thomas

Jesse B. Thomas

Jesse Burgess Thomas was born in Shepherdstown, Virginia . He served as a delegate from the Indiana Territory to the tenth Congress and later served as one of Illinois's first two Senators.- Biography :...

. These two factions formed Illinois' political landscape during its time as a territory and for its first several years of statehood.

Democratic government

Throughout Edwards' three terms as governor, he showed a willingness to surrender his own considerable powers in order to expand participatory governmentParticipatory democracy

Participatory Democracy, also known as Deliberative Democracy, Direct Democracy and Real Democracy , is a process where political decisions are made directly by regular people...

in the Illinois Territory. Before 1812, while Illinois had a first-grade territorial status, Edwards had vast powers to appoint county and local officials; however, he made it his practice to consider local opinion as much as he could when making appointments, often giving weight to petitions signed by local residents. He attempted to do the same for militia officers for a time, letting the men of a unit elect their leaders, but he soon abandoned this policy as impractical.

In 1812, Edwards successfully persuaded Congress to modify a provision of the 1787 Ordinance limiting voting rights to freeholders of 50 acres (20.2 ha) of land. Due to long-running disputes over fraudulently sold lands, very few Illinois frontiersmen could qualify. At Edwards' urging, Congress granted the Illinois Territory universal white male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult males within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification...

, making it the most democratic U.S. territory at the time. In April, Edwards held a referendum on moving to second-grade government, allowing the people of Illinois to elect a legislature and a non-voting delegate to Congress. The referendum passed, and elections were held in October that sent Shadrach Bond

Shadrach Bond

Shadrach Bond was a representative from Illinois Territory to the United States Congress. In 1818, he was elected the first Governor of Illinois, becoming the new state's first chief executive...

to Washington as Illinois' first congressional delegate.

War of 1812

Edwards had not been governor long when Illinois became the scene of fighting during the War of 1812War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. Relations between Illinois settlers and Native Americans worsened throughout the territory during 1810 and 1811. By June 1811, Governor Edwards ordered the construction of a series of blockhouses and called out three companies of militia.

The declaration of war and the Battle of Fort Dearborn in 1812 convinced Edwards that Potawatomi

Potawatomi

The Potawatomi are a Native American people of the upper Mississippi River region. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a member of the Algonquian family. In the Potawatomi language, they generally call themselves Bodéwadmi, a name that means "keepers of the fire" and that was applied...

and Kickapoo

Kickapoo

The Kickapoo are an Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe. According to the Anishinaabeg, the name "Kickapoo" means "Stands here and there". It referred to the tribe's migratory patterns. The name can also mean "wanderer"...

in the territory were preparing to launch a major attack on the southern settlements. In his capacity as commander in chief, Edwards gathered 350 mounted rangers and volunteers near Edwardsville

Edwardsville, Illinois

Edwardsville is a city in Madison County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 24,293. It is the county seat of Madison County and is the third oldest city in the State of Illinois. The city was named in honor of Ninian Edwards, then Governor of the Illinois...

and personally led an expedition north to Peoria

Peoria, Illinois

Peoria is the largest city on the Illinois River and the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, in the United States. It is named after the Peoria tribe. As of the 2010 census, the city was the seventh-most populated in Illinois, with a population of 115,007, and is the third-most populated...

. After burning two Kickapoo villages on the Sangamon River

Sangamon River

The Sangamon River is a principal tributary of the Illinois River, approximately long, in central Illinois in the United States. It drains a mostly rural agricultural area between Peoria and Springfield...

along the way, the militia advanced on Peoria itself. All told, the short campaign burned several villages and inflicted dozens of casualties before returning. The attack angered both the Peoria villagers and the U.S. government because it had been carried out against Native Americans loyal to Black Partridge

Black Partridge (chief)

Black Partridge or Black Pheasant was a 19th century Peoria Lake Potawatomi chieftain...

and Gomo

Chief Gomo

Chief Gomo was a 19th century Potawatomi chieftain. He and his brother Senachwine were among the more prominent war chiefs to fight alongside Black Partridge during the Peoria War.-Biography:...

, two leaders who had not joined Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War

Tecumseh's War or Tecumseh's Rebellion are terms sometimes used to describe a conflict in the Old Northwest between the United States and an American Indian confederacy led by the Shawnee leader Tecumseh...

and were considered friendly to U.S. interests. A second attack under Captain Thomas Craig killed a large number of French settlers from Peoria as well as Potawatomi. In 1813, Illinois and Missouri militia joined a force of United States infantry under Benjamin Howard

Benjamin Howard (Missouri)

Benjamin Howard was a Congressman from Kentucky, governor of Missouri Territory and a brigadier general in the War of 1812....

to drive all Native American villagers away from Peoria and establish Fort Clark.

Edwards' actions alienated those Native Americans friendly to the U.S. in the region. Ninian Edwards, having lost the confidence of the Madison administration, waited out the war in Kentucky. However, he was reappointed to a second and then a third term as territorial governor in 1812 and 1815, and he was also named one of the three U.S. negotiators of the Treaties of Portage des Sioux

Treaties of Portage des Sioux

The Treaties of Portage des Sioux were a series of treaties at Portage des Sioux, Missouri in 1815 that officially were supposed to mark the end of conflicts between the United States and Native Americans at the conclusion of the War of 1812....

in 1815.

Second and third terms

During his nine years as territorial governor, Edwards made a good deal of money through several profitable ventures, including farming, land speculationSpeculation

In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal sum...

, and investment in sawmills, grist mills, and stores.

Edwards' political rivalry with Jesse B. Thomas continued for the rest of his time as governor. Edwards, along with much of the legislature, criticized the territory's judges for their inactivity. Among their complaints were that the judges did not hold court often enough and spent too much time absent from the territory. The legislature passed a bill in 1814 to reform the territory's judicial system. The judges refused to acknowledge the act, claiming that they were outside the jurisdiction of the legislature. In 1815 the issue was resolved by Congress, which passed a law supporting Edwards and the legislature.

In December 1817, Edwards, responding to a movement for statehood led by his ally Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook was a politician from the U.S. state of Illinois.He was born in Scott County, Kentucky into a branch of the prominent Pope family of Kentucky. He moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois, in 1815 and began to practice law...

, recommended to the legislature that Illinois apply for admission to the Union. He also recommended that a census first be taken of the territory, a standard practice, but the legislature rejected this. Legislators, particularly those opposed to slavery, feared that any delay would allow Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

to apply for statehood before Illinois, and that since Missouri was a slave state, this would cause so much turmoil in Congress that it would delay Illinois' admission even longer.

In order to emphasize to Congress that Illinois would be a free state, the legislature passed in January 1818 a bill that would both abolish Illinois' "indentured servant" system of de facto slavery, and prohibit Illinois' future Constitution from reinstating it. Governor Edwards issued his only veto to send the bill back to the legislature, and it was never revised. He made his objections on constitutional grounds, but he also had a conflict of interest as the owner of several slaves himself.

During Edwards' terms as territorial governor, Illinois' population more than tripled, from 12,282 in 1810 to 40,258 in 1818 (a census was finally conducted later that year). The population did not meet the 60,000 threshold the Northwest Ordinance required for a new state, but both Illinoisans and Congress expected continued growth.

Senate career

Illinois quickly proceeded along the steps to statehood. Its constitution was finished in August 1818; elections were held in September; and in October, the first General AssemblyIllinois General Assembly

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois and comprises the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Illinois has 59 legislative districts, with two...

met in Kaskaskia. On October 6, Ninian Edwards stepped down, and Shadrach Bond was inaugurated as Illinois' first governor. The following day the new state legislature voted for Illinois' two members of the U.S. Senate. Edwards was quickly chosen on the first ballot; his rival Thomas was only elected after the fourth. Edwards and Thomas then drew straws to determine their respective terms: Thomas was placed in Class II of the Senate

Classes of United States Senators

The three classes of United States Senators are currently made up of 33 or 34 Senate seats. The purpose of the classes is to determine which Senate seats will be up for election in a given year. The three groups are staggered so that one of them is up for election every two years.A senator's...

and could serve until 1823, while Edwards was placed in Class III and had to face reelection in February 1819. Edwards and Thomas still had to wait for Congress to formally ratify Illinois' constitution and admission to the Union, which it did on November 25. On December 3 the two Senators were finally seated, leaving Edwards with a mere three months in his first term.

Edwards' re-election was more difficult. In four months he had lost the temporary support of Thomas' allies in the General Assembly who had voted for him in 1818. He narrowly defeated Thomas partisan Michael Jones by a vote of 23–19. This may have been due to the influence of the powerful Secretary of State Elias Kane

Elias Kane

Elias Kent Kane was one of the first U.S. Senators from Illinois.He was born in New York City, attended the public schools, and graduated from Yale College in 1813....

, a Thomas ally.

Like most members of Congress during the Era of Good Feelings

Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings was a period in United States political history in which partisan bitterness abated. It lasted approximately from 1815 to 1825, during the administration of U.S...

, Senator Edwards sat as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party. As his second term drew on, he joined the Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

-Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

faction that would develop into the National Republicans after Edwards left office. Edwards voted for the Missouri Compromise

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30'...

in 1820, a bill that Thomas sponsored. He voted against a law reducing prices for federal land, which made both Edwards and Representative Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook was a politician from the U.S. state of Illinois.He was born in Scott County, Kentucky into a branch of the prominent Pope family of Kentucky. He moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois, in 1815 and began to practice law...

targets of criticism at home. On May 6, 1821, Cook married Edwards' daughter Julia.

Ninian Edwards caused trouble for himself when he wrote several articles in the Washington Republican under the pseudonym "A.B." that attacked U.S. Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford

William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as United States Secretary of War from 1815 to 1816 and United States Secretary of the Treasury from 1816 to 1825, and was a candidate for President of the United States in 1824.-Political...

. Edwards alleged that Crawford had known of the impending failure of Illinois' Bank of Edwardsville in 1821, but had not withdrawn federal money from it. Edwards found that none of Crawford's rivals were willing to support his charges, and he was unable to produce corroborating evidence. He resigned his Senate seat on March 4, 1824, to take a job he wanted as the USA's first Minister to Mexico

United States Ambassador to Mexico

The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with Mexico since 1823, when Andrew Jackson was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to that country. Jackson declined the appointment, however, and Joel R. Poinsett became the first U.S. envoy to Mexico in 1825. The rank...

. While en route to his new position, Edwards was called back to Washington to testify before a special House committee concerning the "A.B. Plot". Unable to substantiate his claims, Edwards resigned his diplomatic post, to be replaced by Joel Roberts Poinsett

Joel Roberts Poinsett

Joel Roberts Poinsett was a physician, botanist and American statesman. He was a member of the United States House of Representatives, the first United States Minister to Mexico , a U.S...

.

Back in Illinois, Edwards settled in Belleville

Belleville, Illinois

Belleville is a city in St. Clair County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city has a population of 44,478. It is the eighth-most populated city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area and the most populated city south of Springfield in the state of Illinois. It is the county...

, a town whose site he had once owned before selling off its lots at a profit.

Election of 1826

When he returned to Illinois, Edwards appeared to be a discredited politician. He no longer had a loyal coalition in the General Assembly to re-elect him to the U.S. Senate. His actions in the "A.B. Plot" had made him lose favor with President Adams; therefore he could not expect another federal appointment. In addition, supporters of Andrew JacksonAndrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

were becoming a force in Illinois politics. Illinois frontier voters so admired Jackson that soon, for the first time, they would give their support to a national party, the Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

. Ninian Edwards never criticized Jackson, but as an Adams-Clay Republican Senator he was not part of Jackson's growing coalition. Jacksonians deeply resented Edwards' ally Cook, who had voted against Jackson when the presidential election of 1824

United States presidential election, 1824

In the United States presidential election of 1824, John Quincy Adams was elected President on February 9, 1825, after the election was decided by the House of Representatives. The previous years had seen a one-party government in the United States, as the Federalist Party had dissolved, leaving...

was decided in the House of Representatives.

However, when he ran for governor in 1826, Edwards had the good fortune to enter a three-way race that split the Jacksonians between state Senator Thomas Sloo and Lieutenant Governor Adolphus Hubbard. As a campaign issue, Edwards focused on Illinois' dire financial situation, blaming Sloo and Hubbard and other legislators for it. Edwards won 49.5 percent of the vote to Sloo's 46 percent, with the rest going to Hubbard.

Administration

Edwards' gubernatorial term was another period of rapid growth for Illinois. In the decade from 1820 to 1830, the population again nearly tripled from 55,211 to 157,445. During this era, Illinois was the fastest-growing territory in the world.Edwards' administration was hampered by his conflict with the legislature, primarily over the struggling Bank of Illinois. The bank had been established in 1821, and from the beginning it had been underfunded, its notes had badly depreciated, and it had helped put the state deeply in debt. In his inaugural address Edwards undiplomatically attacked bank officials and politicians alike, accusing them of fraud and perjury. From that point, Edwards had a poor relationship with the General Assembly. During his term the Assembly did eventually pass a bank regulation bill, but it also passed a measure to relieve debtors despite Edwards' objections that the state could not afford it.

In 1827 Illinois established its first penitentiary, at Alton

Alton, Illinois

Alton is a city on the Mississippi River in Madison County, Illinois, United States, about north of St. Louis, Missouri. The population was 27,865 at the 2010 census. It is a part of the Metro-East region of the Greater St. Louis metropolitan area in Southern Illinois...

. That same year, the state received a federal land grant to build the Illinois and Michigan Canal

Illinois and Michigan Canal

The Illinois and Michigan Canal ran from the Bridgeport neighborhood in Chicago on the Chicago River to LaSalle-Peru, Illinois, on the Illinois River. It was finished in 1848 when Chicago Mayor James Hutchinson Woodworth presided over its opening; and it allowed boat transportation from the Great...

, though work did not begin for several years.

Also in 1827, Edwards ordered the Illinois militia to join another war against Native Americans in northern Illinois. The Winnebago War

Winnebago War

The Winnebago War was a brief conflict that took place in 1827 in the Upper Mississippi River region of the United States, primarily in what is now the state of Wisconsin. Not quite a war, the hostilities were limited to a few attacks on American civilians by a portion of the Winnebago Native...

, fought between white settlers and members of the Ho-Chunk

Ho-Chunk

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Winnebago, are a tribe of Native Americans, native to what is now Wisconsin and Illinois. There are two federally recognized Ho-Chunk tribes, the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin and Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska....

tribe, broke out in Wisconsin (then part of the Michigan Territory

Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan...

) but spread to the lead-mining region around Galena

Galena, Illinois

Galena is the county seat of, and largest city in, Jo Daviess County, Illinois in the United States, with a population of 3,429 in 2010. The city is a popular tourist destination known for its history, historical architecture, and ski and golf resorts. Galena was the residence of Ulysses S...

. Edwards dispatched the militia and ordered 600 more men to be recruited in Sangamon County

Sangamon County, Illinois

Sangamon County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 197,465, which is an increase of 4.5% from 188,951 in 2000...

. The show of force convinced the Ho-Chunk to surrender.

After the war, Edwards urged the federal government to remove

Indian Removal

Indian removal was a nineteenth century policy of the government of the United States to relocate Native American tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river...

the remaining Native Americans from northern Illinois, claiming that their presence violated "the rights of a sovereign and independent state", and hinting that he might dispatch the militia again to force them out. The federal government applied diplomatic pressure, and on July 29, 1829, the Potawatomi, Ottowa, and Ojibwe ceded 3000 square miles (7,770 km²) of northern land to the State of Illinois; the Winnebago made a cession in August.

Later life

Under the 1818 constitution, governors were limited to a single term. When Edwards' ended on December 6, 1830, he returned to private life. He ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1832 and lost. Edwards devoted himself to charitable medical work in Belleville, giving free care to local residents. A choleraCholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

epidemic came through the area in 1833, carried by Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

's troops during the Black Hawk War

Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a brief conflict fought in 1832 between the United States and Native Americans headed by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted soon after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis, and Kickapoos known as the "British Band" crossed the Mississippi River into the U.S....

. Edwards stayed in the town to care for his patients and caught the disease, dying on July 20. Ninian Edwards was interred in Belleville, but he was later moved to Springfield

Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the third and current capital of the US state of Illinois and the county seat of Sangamon County with a population of 117,400 , making it the sixth most populated city in the state and the second most populated Illinois city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area...

's Oak Ridge Cemetery

Oak Ridge Cemetery

Oak Ridge Cemetery is a cemetery located in Springfield, Illinois in the United States.Lincoln's Tomb, which serves as the final resting place of Abraham Lincoln, his wife and all but one of his children, is located at Oak Ridge...

.

Family

Three of Edwards' sons and one son-in-law followed him into politics. Ninian Wirt Edwards (1809–1889), named for his father and his father's childhood tutor William Wirt, served as Illinois Attorney GeneralIllinois Attorney General

The Illinois Attorney General is the highest legal officer of the state of Illinois in the United States. Originally an appointed office, it is now an office filled by election through universal suffrage...

, in the General Assembly, and as Illinois' first Superintendent of Public Instruction. He was married to Elizabeth Porter Todd, a sister of Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Ann Lincoln was the wife of the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, and was First Lady of the United States from 1861 to 1865.-Life before the White House:...

. Their daughter Julia Cook Edwards married Edward Lewis Baker, editor of the Illinois State Journal and son of Congressman David Jewett Baker.

Another son, Albert Gallatin Edwards

Albert Gallatin Edwards

Albert Gallatin Edwards was an Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury under President of the United States Abraham Lincoln and founder of brokerage firm A. G. Edwards....

(1812–1892), was an assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury under U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

. In 1887 he founded the brokerage firm A. G. Edwards in Saint Louis, Missouri. A third son, Benjamin S. Edwards

Benjamin S. Edwards

Benjamin S. Edwards was an Illinois lawyer, politician, and judge.-Biography:...

(1818–1886), established a successful law practice in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the third and current capital of the US state of Illinois and the county seat of Sangamon County with a population of 117,400 , making it the sixth most populated city in the state and the second most populated Illinois city outside of the Chicago Metropolitan Area...

and served as a judge in Illinois' Thirteenth Circuit. Ninian Edwards' daughter, Julia Edwards Cook, married Congressman Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook

Daniel Pope Cook was a politician from the U.S. state of Illinois.He was born in Scott County, Kentucky into a branch of the prominent Pope family of Kentucky. He moved to Kaskaskia, Illinois, in 1815 and began to practice law...

. Their son, John Cook, was a mayor of Springfield and a general in the Union Army

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Legacy

Edwards County, IllinoisEdwards County, Illinois

Edwards County is a county located in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 census, it has a population of 6,721, which is a decrease of 3.6% from 6,971 in 2000...

was named for him, as is the St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

Metro-East

Metro-East

Metro East is a region in Illinois that comprises the eastern suburbs of St. Louis, Missouri, United States. It encompasses five Southern Illinois counties in the St. Louis Metropolitan Statistical Area. The region's most populated city is Belleville at 45,000 residents...

area city of Edwardsville, Illinois

Edwardsville, Illinois

Edwardsville is a city in Madison County, Illinois, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 24,293. It is the county seat of Madison County and is the third oldest city in the State of Illinois. The city was named in honor of Ninian Edwards, then Governor of the Illinois...

. Both were named for him during his time as territorial governor. The territorial legislature named Edwards County, while Edwardsville was named by its founder, Thomas Kirkpatrick.