Matthew Stirling

Encyclopedia

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

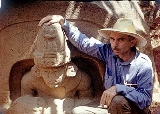

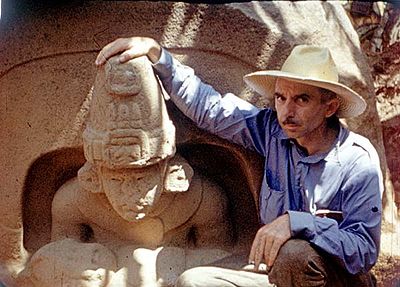

ethnologist, archaeologist and later an administrator at several scientific institutions in the field. He is best known for his discoveries relating to the Olmec

Olmec

The Olmec were the first major Pre-Columbian civilization in Mexico. They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco....

civilization.

Stirling began his career with extensive ethnological work in the United States, New Guinea

New Guinea

New Guinea is the world's second largest island, after Greenland, covering a land area of 786,000 km2. Located in the southwest Pacific Ocean, it lies geographically to the east of the Malay Archipelago, with which it is sometimes included as part of a greater Indo-Australian Archipelago...

and Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

, before directing his attention to the Olmec civilization and its possible primacy among the pre-Columbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

societies of Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a region and culture area in the Americas, extending approximately from central Mexico to Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, within which a number of pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 15th and...

. His discovery of, and excavations at, various sites attributed to Olmec culture in the Mexican Gulf Coast

Gulf Coast of Mexico

The Gulf Coast of Mexico stretches along the Gulf of Mexico from the border with the United states at Matamoros, Tamaulipas all the way to the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula at Cancún. It includes the coastal regions along the Bay of Campeche. Major cities include Veracruz, Tampico, and...

region significantly contributed towards a better understanding of the Olmecs and their culture. He then began investigating links between the different civilizations in the region. Apart from his extensive field work and publications, later in his career Stirling proved to be an able administrator of academic and research bodies, who served on directorship boards of a number of scientific organizations.

Early life and work

Matthew was born in SalinasSalinas, California

Salinas is the county seat and the largest municipality of Monterey County, California. Salinas is located east-southeast of the mouth of the Salinas River, at an elevation of about 52 feet above sea level. The population was 150,441 at the 2010 census...

, California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

, where his father managed the Southern Pacific Milling Company. Most of his childhood days were spent on his grandfather's ranch where he first developed an interest in antiquity, collecting arrowheads and researching artefacts.

Stirling majored in anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

under Alfred L. Kroeber

Alfred L. Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber was an American anthropologist. He was the first professor appointed to the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, and played an integral role in the early days of its Museum of Anthropology, where he served as director from 1909 through...

, graduating from of the University of California

University of California

The University of California is a public university system in the U.S. state of California. Under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, the University of California is a part of the state's three-tier public higher education system, which also includes the California State University...

in 1920. His interest in the Olmecs began in about 1918, when he saw a picture of a "crying-baby" blue jade masquette, published by Thomas Wilson of the Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

in 1898. When he traveled to Europe with his family after graduation, he found the masquette itself in the Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

Museum, and intrigued by the Olmec culture, took time to look at other specimens in the Maximilian Collection in Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, and later, in Madrid

Madrid

Madrid is the capital and largest city of Spain. The population of the city is roughly 3.3 million and the entire population of the Madrid metropolitan area is calculated to be 6.271 million. It is the third largest city in the European Union, after London and Berlin, and its metropolitan...

.

Stirling was a teaching fellow at the University of California during 1920-21. He then joined the Smithsonian Institution, as a museum aide and assistant curator in its Division of Ethnology at the National Museum. He worked there until 1925. He located several more Olmec pieces in the museum. During this period, he also obtained his Masters Degree in Anthropology from the George Washington University

George Washington University

The George Washington University is a private, coeducational comprehensive university located in Washington, D.C. in the United States...

. He was later, in 1943, to receive a Doctorate in Science from Tampa University.

He excavated on Weedon Island for the Bureau of American Ethnology

Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior Department to the Smithsonian Institution...

(BAE) in 1923-24, and at Arikara

Arikara

Arikara are a group of Native Americans in North Dakota...

villages in Mobridge, South Dakota

South Dakota

South Dakota is a state located in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux American Indian tribes. Once a part of Dakota Territory, South Dakota became a state on November 2, 1889. The state has an area of and an estimated population of just over...

, during the summer of 1924. Stirling resigned from the Smithsonian to lead a 400 member, Smithsonian Institution-Dutch Colonial Government, expedition to New Guinea in 1925. He conducted ethnological and physical anthropological studies among the indigenous peoples there, and collected a number of natural history specimens, which now form one of the most valuable collections in the National Museum.

He returned to take over as chief of the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology in 1928. He retained the position until 1957, his title changing to director in 1947. He went to Ecuador in 1931-32, conducting ethnological studies of the Jivaro, as part of Donald C. Beatty's expedition. He also worked along the Gulf Coast, directing archaeological digs in Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

and Georgia

Georgia (U.S. state)

Georgia is a state located in the southeastern United States. It was established in 1732, the last of the original Thirteen Colonies. The state is named after King George II of Great Britain. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the United States Constitution, on January 2, 1788...

.

Stirling was intrigued by Marshall Saville

Marshall Howard Saville

Marshall Howard Saville was an American archaeologist, born at Rockport, Mass. He studied anthropology at Harvard , engaged in field work under F. W. Putnam, and made important discoveries among the mound builders in southern Ohio. After 1903 he was professor of American archæology at Columbia...

's two 1929 reports, Votive Axes from Ancient Mexico. Subsequent discussions with Saville launched Stirling into a phase of his career which would be focused on what was then beginning to be called Olmec culture.

The Olmec

The Olmec were an ancient Pre-Columbian people living in south-central MexicoMexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, in the modern-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco, from about 1200 BC to 400 BC. They are claimed by many to be the mother culture of every primary element common to later Mesoamerican civilizations.

The name "Olmec" means "rubber people" in Nahuatl

Nahuatl

Nahuatl is thought to mean "a good, clear sound" This language name has several spellings, among them náhuatl , Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In a back formation from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called Nahua...

, the language of the Aztecs. It was the Aztec name for the people who lived in this area at the time of Aztec dominance, referring to them as those who supplied the rubber balls used for games. Early modern explorers applied the name "Olmec" to ruins and art from this area before it was understood that these had been already abandoned more than a thousand years before the time of the people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec".

Stirling and history of the Olmecs

By 1929, Stirling had begun suspecting that the artifacts emerging out of Mexico belonged to a time much earlier than attributed to the Olmecs. From the BAE, he directed excavations in fringes of the area thought to be MayaMaya civilization

The Maya is a Mesoamerican civilization, noted for the only known fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Initially established during the Pre-Classic period The Maya is a Mesoamerican...

. He himself travelled in 1938 to the western margin and concentrated on the Tres Zapotes

Tres Zapotes

Tres Zapotes is a Mesoamerican archaeological site located in the south-central Gulf Lowlands of Mexico in the Papaloapan River plain. Tres Zapotes is sometimes referred to as the third major Olmec capital , although Tres Zapotes' Olmec phase constitutes only a portion of the site’s history, which...

site. He noted the position of the colossal head - surrounded by four mounds - and the presence of a vast mound group in the area. He interested the National Geographic Society

National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society , headquartered in Washington, D.C. in the United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational institutions in the world. Its interests include geography, archaeology and natural science, the promotion of environmental and historical...

enough to be granted funds for excavation. This began a sixteen year association with the site.

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

, a date considered by many to be too early for a Mesoamerican civilization. An "8" would mean a date of 363 CE

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

. The Stirlings opted for the earlier date, to the consternation of many in the archaeological community.

They were proven correct in 1970, when the top half of Stela C was discovered, and the earlier date of 7.16.6.16.18, or 32 BCE, was confirmed.

He also led the first of several expeditions to San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán is the collective name for three related archaeological sites -- San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlán, and Potrero Nuevo -- located in the southeast portion of the Mexican state of Veracruz. From 1200 BCE to 900 BCE, it was the major center of Olmec culture...

(1938), La Venta

La Venta

La Venta is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Olmec civilization located in the present-day Mexican state of Tabasco. Some of the artifacts have been moved to the museum "Parque - Museo de La Venta", which is in Villahermosa, the capital of Tabasco....

(1939–40) and Cerro de las Mesas

Cerro de las Mesas

Cerro de las Mesas, meaning "hill of the altars" in Spanish, is an archaeological site in the Mexican state of Veracruz, in the Mixtequilla area of the Papaloapan River basin...

(1940–41). In 1941, Stirling unearthed a large carved stone monument in Izapa

Izapa

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it was occupied during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, near the base of the Tacaná volcano), the fourth largest mountain in...

, which he labeled Stela 5.

Stirling was unable to return to La Venta until 1942, due to World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. When he did, he was to excavate several important artifacts. He then left for Tuxtla Gutiérrez

Tuxtla Gutiérrez

Tuxtla Gutiérrez is the capital and largest city of the Mexican state of Chiapas. It is considered to be the state’s most modern city, with most of its public buildings dating from the 20th century. One exception to this is the San Marcos Cathedral which began as a Dominican parish church built in...

to attend a conference on the Maya and Olmec cultures, one that was to become a defining moment in modern ideas about the Olmec. It was here that Miguel Covarrubias

Miguel Covarrubias

José Miguel Covarrubias Duclaud was a Mexican painter and caricaturist, ethnologist and art historian among other interests. In 1924 at the age of 19 he moved to New York City armed with a grant from the Mexican government, tremendous talent, but very little English speaking skill. Luckily,...

and Dr. Alfonso Caso

Alfonso Caso

Alfonso Caso y Andrade was an archaeologist who made important contributions to pre-Columbian studies in his native Mexico. Caso believed that the systematic study of ancient Mexican civilizations was an important way to understand Mexican cultural roots...

first presented the case for the Olmec culture as being the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica, pre-dating even the Maya. Stirling supported their hypothesis, as he did Covarrubias in his interpretation of Olmec art. For example, Monument 1 at Río Chiquito

Río Chiquito

The Río Chiquito is a river in the municipality of Ponce, Puerto Rico. This river feeds into the Rio Portugues in the sector called Parras. It has its origin in the mountains west of Montes Llanos. Rio Chiquito is fed by Quebrada del Pastillo...

and Monument 3 at Potrero Nuevo were, according to Stirling, the mythological union of a jaguar and a woman that produced "almost jaguar children".

It would be nearly 15 years before radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating is a radiometric dating method that uses the naturally occurring radioisotope carbon-14 to estimate the age of carbon-bearing materials up to about 58,000 to 62,000 years. Raw, i.e. uncalibrated, radiocarbon ages are usually reported in radiocarbon years "Before Present" ,...

finally confirmed that the Olmec pre-dated the Maya. The Olmec culture is generally considered to have lasted from 1400 BCE

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

until 400 BCE.

Other work

Stirling began searching for links between Mesoamerican and South American cultures in PanamaPanama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

, Ecuador, and Costa Rica

Costa Rica

Costa Rica , officially the Republic of Costa Rica is a multilingual, multiethnic and multicultural country in Central America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, Panama to the southeast, the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Caribbean Sea to the east....

from 1948 to 1954. He was also the chief organizer of the seven-volume Handbook of South American Indians.

He conducted excavations in the Linea Vieja lowlands of Costa Rica in the 1960s. Concentrating on tombs, he dug at five sites between Siquirres and Guapiles, and published a series of C- 14 dates ranging from 1440 to 1470 A.D, and arranged much of the pottery excavated in an approximate chronological sequence.

In the Sierra de Ameca between Ahualulco de Mercado and Ameca, Jalisco, a large number of stone spheres, many of which are almost perfectly spherical, can be found. Their generally spherical shape led people to suspect they were manmade stone balls, called petrosphere

Petrosphere

In archaeology, a petrosphere is the name for any spherical man-made object of any size that is composed of stone. These mainly prehistoric artefacts may have been created and/or selected, but altered in some way to perform their specific function, including carving and painting.Several classes of...

s, created by an unknown culture. In 1967, Stirling examined these stone spheres in the field. As a result of this examination, he and his colleagues hypothesized that they were of geological origin. A later expedition and subsequent petrographic and other laboratory analyses of samples of the stone balls confirmed this suspicion. Their interpretation of the data collected in both field and laboratory is that these stone balls were formed by high temperature nucleation of glassy material within an ashfall tuff

Tuff

Tuff is a type of rock consisting of consolidated volcanic ash ejected from vents during a volcanic eruption. Tuff is sometimes called tufa, particularly when used as construction material, although tufa also refers to a quite different rock. Rock that contains greater than 50% tuff is considered...

, as a result of tertiary volcanism

Volcanism

Volcanism is the phenomenon connected with volcanoes and volcanic activity. It includes all phenomena resulting from and causing magma within the crust or mantle of a planet to rise through the crust and form volcanic rocks on the surface....

.

Other positions held

Stirling was president of the Anthropological Society of Washington in 1934-1935 and vice president of the American Anthropological AssociationAmerican Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association is a professional organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 11,000 members, the Arlington, Virginia based association includes archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, biological anthropologists, linguistic...

in 1935–36. He received the National Geographic Society's Franklyn L. Burr Award for meritorious service in 1939, 1941 (shared with his wife Marion) and 1958. He was also on the Ethnographic Board, which was the Smithsonian’s effort to make its scientific research available to the military agencies during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

After his retirement, Stirling was a Smithsonian research associate, a National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

collaborator, and member of the National Geographic Committee on Research and Exploration.

Stirling died in early 1975, aged 78, after a period of illness associated with cancer.

Book collection

Marion Stirling donated around 5000 volumes from Matthew Stirling's library to the Boundary End Archaeology Research Center (earlier the Center for Maya Research). They include a collection of scholarly pamphlets and reprints from the mid-19th century on, complete runs of the American Anthropologist (1881 - ); American Antiquity (1935 - ), Bulletins 1-200 and Annual Reports 1-48 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, and all the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural HistoryAmerican Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History , located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, United States, is one of the largest and most celebrated museums in the world...

.

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology

The museum, in the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

, displays 165 Dyak

Dyak

Dyak may refer to one of the following.*Dayak people, also called "Dyak", a native tribe of Borneo*Dyak a historical position of head of office in Russia...

and Papuan objects, including steel axes, basketry, arrows and wooden boxes, from Borneo

Borneo

Borneo is the third largest island in the world and is located north of Java Island, Indonesia, at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia....

, donated by Stirling.

Films by Stirling

Preserved at the Human Studies Film ArchiveHuman Studies Film Archive

The Human Studies Film Archives , part of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC, is devoted to preserving, documenting and providing access to anthropological moving image materials...

, Suitland, Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

- Exploring Hidden Mexico - Documents excavations at La Venta and Cerro de las Mesas.

- Hunting Prehistory on Panama’s Unknown North Coast - Documents the 1952 excavations of sites in Northern PanamaPanamaPanama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

. - Aboriginal Darien : Past and Present - Documents the flora, fauna and ethnography of parts of Panama through a journey in 1954.

- On the Trail of Prehistoric America - Documents an Ecuador expedition in 1957, along with brief ethnographic footage of the ColoradoColoradoColorado is a U.S. state that encompasses much of the Rocky Mountains as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the Great Plains...

Indians. - Mexico in Fiesta Masks

- Uncovering an Ancient Mexican Temple

- Exploring Panama’s Prehistoric Past

- Uncovering Mexico’s Forgotten Treasures