Maori mythology

Encyclopedia

Legend

A legend is a narrative of human actions that are perceived both by teller and listeners to take place within human history and to possess certain qualities that give the tale verisimilitude...

s of the Māori of New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

may usefully be divided. The rituals, beliefs, and the world view of Māori society were ultimately based on an elaborate mythology

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

that had been inherited from a Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

n homeland and adapted and developed in the new setting (Biggs 1966:448).

Missionaries

Little of the extensive body of Māori mythology and tradition was recorded in the early years of European contact. The missionaries had the best opportunity to get the information, but failed to do so at first, in part because their knowledge of the language was imperfect. Most of the missionaries who did master the language were unsympathetic to Māori beliefs, regarding them as 'puerile beliefs', or even 'works of the devil'. Exceptions to this general rule were J. F. Wohlers of the South IslandSouth Island

The South Island is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean...

, Richard Taylor

Richard Taylor (missionary)

Richard Taylor was a C.M.S. missionary in New Zealand. He was present at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, but is perhaps most notable for the numerous books he wrote on the natural and cultural environment of New Zealand in his time...

, who worked in the Taranaki and Wanganui River

Wanganui River

The Wanganui River is located in the western South Island of New Zealand. It flows northwest for 55 kilometres from its headwaters in the Southern Alps, entering the Tasman Sea near Lake Ianthe, 40 kilometres southwest of Hokitika....

areas, and William Colenso

William Colenso

William Colenso was a Cornish Christian missionary to New Zealand, and also a printer, botanist, explorer and politician.-Life:Born in Penzance, Cornwall, he was the cousin of John William Colenso, Bishop of Natal...

who lived at the Bay of Islands

Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area in the Northland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. Located 60 km north-west of Whangarei, it is close to the northern tip of the country....

and also in Hawke's Bay

Hawke's Bay

Hawke's Bay is a region of New Zealand. Hawke's Bay is recognised on the world stage for its award-winning wines. The regional council sits in both the cities of Napier and Hastings.-Geography:...

. "The writings of these men are among our best sources for the legends of the areas in which they worked" (Biggs 1966:447).

Non-missionary collectors

In the 1840s Edward Shortland, Sir George Grey, and other non-missionaries began to collect the myths and traditions. At that time many Māori were literate in their own language and the material collected was, in general, written by Māori themselves in the same style as they spoke. The new medium seems to have had minimal effect on the style and content of the stories. Genealogies, songs, and narratives were written out in full, just as if they were being recited or sung. Many of these early manuscripts have been published, and today the scholar has access to a great body of material (more than for any other area of the Pacific) containing multiple versions of the great myth cycles known in the rest of Polynesia, as well as of the local traditions pertaining only to New Zealand. A great deal of the best material is found in two books, Nga Mahi a nga Tupuna (The Deeds of the Ancestors), collected by Sir George Grey and translated as Polynesian Mythology; and Ancient History of the Māori (six volumes), edited by John White (Biggs 1966:447).Forms of the legends

The three forms of expression prominent in Māori and Polynesian oral literatureOral literature

Oral literature corresponds in the sphere of the spoken word to literature as literature operates in the domain of the written word. It thus forms a generally more fundamental component of culture, but operates in many ways as one might expect literature to do...

are genealogical recital, poetry, and narrative prose.

Genealogical recital

The reciting of genealogies (whakapapaWhakapapa

Whakapapa , or genealogy, is a fundamental principle that permeates the whole of Māori culture. However, it is more than just a genealogical 'device'...

) was particularly well developed in Māori oral literature, where it served several functions in the recounting of tradition. Firstly it served to provide a kind of time scale which unified all Māori myth

Mythology

The term mythology can refer either to the study of myths, or to a body or collection of myths. As examples, comparative mythology is the study of connections between myths from different cultures, whereas Greek mythology is the body of myths from ancient Greece...

, tradition

Tradition

A tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

, and history

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

, from the distant past to the present. It linked living people to the gods and the legendary heroes. By quoting appropriate genealogical lines, a narrator emphasised his or her connection with the characters whose deeds were being described, and that connection also proved that the narrator had the right to speak of them. "In the cosmogonic genealogies, to be described later, genealogical recital is revealed as a true literary form. What appears at first sight to be a mere listing of names is in fact a cryptic account of the evolution of the universe"' (Biggs 1966:447).

Poetry

Māori poetry was always sung or chanted; musical rhythms rather than linguistic devices served to distinguish it from prose. RhymeRhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words and is most often used in poetry and songs. The word "rhyme" may also refer to a short poem, such as a rhyming couplet or other brief rhyming poem such as nursery rhymes.-Etymology:...

or assonance

Assonance

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds to create internal rhyming within phrases or sentences, and together with alliteration and consonance serves as one of the building blocks of verse. For example, in the phrase "Do you like blue?", the is repeated within the sentence and is...

were not devices used by the Māori; only when a given text is sung or chanted will the metre become apparent. The lines are indicated by features of the music. The language of poetry tends to differ stylistically from prose. Typical features of poetic diction are the use of synonyms or contrastive opposites, and the repetition of key words. "Archaic words are common, including many which have lost any specific meaning and acquired a religious mystique. Abbreviated, sometimes cryptic utterances and the use of certain grammatical constructions not found in prose are also common" (Biggs 1966:447-448).

Prose narrative

Prose narrative forms the great bulk of Māori legendary material. Some appears to have been sacred or esoteric, but many of the legends were well-known stories told as entertainment in the long nights of winter. "Nevertheless, they should not be regarded simply as fairy tales to be enjoyed only as stories. The Māui myth, for example, was important not only as entertainment but also because it embodied the beliefs of the people concerning such things as the origin of fire, of death, and of the land in which they lived. The ritual chants concerning firemaking, fishing, death, and so on made reference to Māui and derived their power from such reference" (Biggs 1966:448).Myths

The Māori understanding of the development of the universe was expressed in genealogical form. These genealogies appear in many versions, in which several symbolic themes constantly recur. "Evolution may be likened to a series of periods of darkness (pō) or voids (kore), each numbered in sequence or qualified by some descriptive term. In some cases the periods of darkness are succeeded by periods of light (ao). In other versions the evolution of the universe is likened to a tree, with its base, tap roots, branching roots, and root hairs. Another theme likens evolution to the development of a child in the womb, as in the sequence “the seeking, the searching, the conception, the growth, the feeling, the thought, the mind, the desire, the knowledge, the form, the quickening”. Some, or all, of these themes may appear in the same genealogy" (Biggs 1966:448).

The cosmogonic genealogies are usually brought to a close by the two names Rangi and Papa (father sky and mother earth). The marriage of this celestial pair produced the gods and, in due course, all the living things of the earth (Biggs 1966:448).

The earliest full account of the origins of gods and the first human beings is contained in a manuscript entitled Nga Tama a Rangi (The Sons of Heaven), written in 1849 by Wī Maihi Te Rangikāheke, of the Ngāti Rangiwewehi tribe of Rotorua

Rotorua

Rotorua is a city on the southern shores of the lake of the same name, in the Bay of Plenty region of the North Island of New Zealand. The city is the seat of the Rotorua District, a territorial authority encompassing the city and several other nearby towns...

. The manuscript "gives a clear and systematic account of Māori religious beliefs and beliefs about the origin of many natural phenomena, the creation of woman, the origin of death, and the fishing up of lands. No other version of this myth is presented in such a connected and systematic way, but all early accounts, from whatever area or tribe, confirm the general validity of the Rangikāheke version. It begins as follows: 'My friends, listen to me. The Māori people stem from only one source, namely the Great-heaven-which-stands-above, and the Earth-which-lies-below. According to Europeans, God made heaven and earth and all things. According to the Māori, Heaven (Rangi) and Earth (Papa) are themselves the source' " (Biggs 1966:448).

Corpus of Māori myths

According to Biggs (1966:448), the main corpus of Māori mythology unfolds in three story complexes or cycles, which are:- The cosmogonic genealogies relating the origins of gods and people

-

- Rangi and PapaRangi and PapaIn Māori mythology the primal couple Rangi and Papa appear in a creation myth explaining the origin of the world. In some South Island dialects, Rangi is called Raki or Rakinui.-Union and separation:...

- Hine-nui-te-pōHine-nui-te-poHine-nui-te-pō is a goddess of night and death and the ruler of the underworld in Māori mythology. She is a daughter of Tāne. She fled to the underworld because she discovered that Tāne, whom she had married, was also her father. The red colour of sunset comes from her.All of the children of Rangi...

- Rangi and Papa

- The Māui complex of myths

-

- MāuiMaui (Maori mythology)In Māori mythology, Māui is a culture hero famous for his exploits and his trickery.-Māui's birth:The offspring of Tū increased and multiplied and did not know death until the generation of Māui-tikitiki . Māui is the son of Taranga, the wife of Makeatutara...

- IrawaruIrawaruIn Māori mythology, Irawaru is the origin of the dog. He is the husband of Hinauri, the sister of Māui. Māui becomes annoyed with Irawaru and stretches out his limbs, turning him into a dog. In some stories, Irawaru as a dog eats faeces...

- Tinirau and KaeTinirau and KaeIn Māori mythology, Tinirau is a guardian of fishes. He is a son of Tangaroa, the god of the sea. His home at Motutapu is surrounded with pools for breeding fish. He also has several pet whales....

- Māui

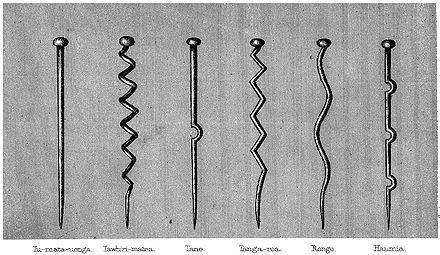

- The Tāwhaki complex of myths

-

- TāwhakiTāwhakiIn Māori mythology, Tāwhaki is a semi-supernatural being associated with lightning and thunder.-Genealogy:The genealogy of Tāwhaki varies somewhat in different accounts. In general, Tāwhaki is a grandson of Whaitiri, a cannibalistic goddess who marries the mortal Kaitangata , thinking that he...

- WahieroaWahieroaIn Māori mythology, Wahieroa is a son of Tāwhaki, and father of Rātā.Tāwhaki was attacked and left for dead by two of his brothers-in-law, jealous that their wives preferred the handsome Tāwhaki to them. He was nursed back to health by his wife Hinepiripiri. She helped him back to their house, and...

- RātāRata (Maori mythology)In Māori mythology, accounts vary somewhat as to the ancestry of Rātā. Usually he is a grandson of Tāwhaki and son of Wahieroa. Wahieroa is treacherously killed by Matuku-tangotango, an ogre...

- Matuku-tangotangoMatuku-tangotangoIn Māori mythology, Matuku-tangotango is an ogre who kills Wahieroa the son of Tāwhaki. In some versions, Matuku lives in a cave called Putawarenuku. Rātā, the son of Wahieroa, sets off to avenge his murdered father, and arrives at last at Matuku's village. He hears from Matuku's servant that at...

- TūwhakararoTuwhakararoIn Māori mythology, Tūwhakararo is a chief in Hawaiki. Tūwhakararo went on a visit to the Āti Hāpai people, whose chief, Poporokewa, had married Tūwhakararo's sister Mairatea. In a wrestling match he was treated unfairly, and was killed in a treacherous manner...

- WhakatauWhakatauIn Māori mythology, Whakatau is a son of Tūwhakararo and Apakura. One day Apakura throws her apron into the sea, and a sea deity named Rongotakawhiu takes it and works it into human form, and Whakatau is born. The sea deity teaches him the arts of enchantment. As the child grows older, people see...

- Tāwhaki

Traditions

"Every Māori social group had its own body of traditional belief which validated its claims to the territory it occupied, gave authority to those of high rank, and justified the group's external relationships with other groups. These purposes were served because the members of the groups concerned believed that the traditions were true records of past events, and they acted accordingly. Alliances between groups were facilitated if it was believed that they shared a common heritage, and the commoner's respect for and fear of his chief were based, in part at least, on his belief in the semi-divine ancestry of those of high rank" (Biggs 1966:450)."Traditions, as opposed to myths, tell of incidents which are for the most part humanly possible. Genealogical links with the present place them within the past millennium. They are geographically located in New Zealand and knowledge of them is confined to this country" (Biggs 1966:448).

Corpus of Māori tradition

According to Biggs (1966:451), tradition may be divided into three types:Discovery or origin traditions

There were two major discovery or origin traditions. One of these traditions names KupeKupe

In the Māori mythology of some tribes, Kupe was involved in the Polynesian discovery of New Zealand.-Contention:There is contention concerning the status of Kupe. The contention turns on the authenticity of later versions of the legends, the so-called 'orthodox' versions closely associated with S....

as the discoverer of New Zealand. The second group of traditions regards Toi

Toi

Toi or TOI may refer to:* Toi , the Biblical king of Hamath* Toi , a masculine name in Māori and other Polynesian languages* Toi, Shizuoka, Japan* TOI , a group of electronic folk rock musicians in the Philippines...

as the first important origin ancestor. "Both traditions were current over wide but apparently complementary areas of the North Island. Attempts to place the two in a single chronological sequence are misguided, since there is no reliable evidence that they ever formed part of the same body of traditional lore" (Biggs 1966:451).

- According to the tribes of North AucklandAucklandThe Auckland metropolitan area , in the North Island of New Zealand, is the largest and most populous urban area in the country with residents, percent of the country's population. Auckland also has the largest Polynesian population of any city in the world...

and the west coast of the North Island, KupeKupeIn the Māori mythology of some tribes, Kupe was involved in the Polynesian discovery of New Zealand.-Contention:There is contention concerning the status of Kupe. The contention turns on the authenticity of later versions of the legends, the so-called 'orthodox' versions closely associated with S....

sailed to New Zealand from HawaikiHawaikiIn Māori mythology, Hawaiki is the homeland of the Māori, the original home of the Māori, before they travelled across the sea to New Zealand...

, after murdering a man called HoturapaHoturapaIn Māori tradition, Hoturapa was a chief of Hawaiki. His wife Kuramarotini owned the canoe Matahourua. One day, Hoturapa and his wife went out fishing in the Matahourua with their friend Kupe. Kupe tricked Hoturapa to dive into the water to free one of the lines. Once Hoturapa was overboard, Kupe...

, and making off with his wife, KuramarotiniKuramarotiniIn Māori mythology, Kuramarotini was the daughter of Toto, a chief of Hawaiki. Toto made a gift to her of the canoe Matahourua, in which she went out fishing with her husband Hoturapa and their friend Kupe. Kupe tricked Hoturapa to dive into the water to free one of the lines...

. Traditional songs recount Kupe's travels along the coast of New Zealand. Kupe sailed back to Hawaiki and never came back to the land he discovered. However, others came to New Zealand according to his directions (Biggs 1966:451). - ToiToi (name)Toi is a fairly common man's name in Māori and other Polynesian languages.The best known men named Toi are the following from Māori legendary history, who are sometimes confused with one another:...

(Toi-kai-rākau, or Toi-the-wood-eater) is the traditional origin ancestor of the tribes of the East Coast of the North Island. Their traditions make no mention of his coming to New Zealand, and the inference is that he was born there. The TūhoeTuhoeNgāi Tūhoe , a Māori iwi of New Zealand, takes its name from an ancestral figure, Tūhoe-pōtiki. The word tūhoe literally means "steep" or "high noon" in the Māori language...

tribe of the inland Bay of PlentyBay of PlentyThe Bay of Plenty , often abbreviated to BOP, is a region in the North Island of New Zealand situated around the body of water of the same name...

, say that Toi's 'ancestor' Tiwakawaka was the first to settle the country, "but only his name is remembered" (Biggs 1966:451). Tiwakawaka is actually the name of a bird, the fantailNew Zealand FantailThe New Zealand Fantail is a small insectivorous bird. A common fantail found in the South Island of New Zealand, also in the North Island as subspecies Rhipidura fuliginosa placabilis, the Chatham Islands as Rhipidura fuliginosa penita and formerly the Lord Howe Island as Rhipidura fuliginosa...

.

Migration and settlement traditions

- Migration traditions are numerous, and pertain to small areas and to small groups of tribes. "Certain tribes appear to have emphasised their canoe migration traditionMaori migration canoesVarious Māori traditions recount how their ancestors set out from their homeland in great ocean-going canoes . Some of these traditions name a mythical homeland called Hawaiki....

and descent from crew members more than the others. In particular, the HaurakiHaurakiHauraki is a suburb of Auckland, New Zealand. It is under the local governance of the North Shore City Council.The population was 5,631 in the 2006 Census, an increase of 261 from 2001.-Education:...

, WaikatoWaikatoThe Waikato Region is a local government region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato, Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsula, the northern King Country, much of the Taupo District, and parts of Rotorua District...

, and King CountryKing CountryThe King Country is a region of the western North Island of New Zealand. It extends approximately from the Kawhia Harbour and the town of Otorohanga in the north to the upper reaches of the Whanganui River in the south, and from the Hauhungaroa and Rangitoto Ranges in the east to near the Tasman...

tribes (TainuiTainuiTainui is a tribal waka confederation of New Zealand Māori iwi. The Tainui confederation comprises four principal related Māori iwi of the central North Island of New Zealand: Hauraki, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Raukawa and Waikato...

canoe) and the RotoruaRotoruaRotorua is a city on the southern shores of the lake of the same name, in the Bay of Plenty region of the North Island of New Zealand. The city is the seat of the Rotorua District, a territorial authority encompassing the city and several other nearby towns...

and TaupoTaupoTaupo is a town on the shore of Lake Taupo in the centre of the North Island of New Zealand. It is the seat of the Taupo District Council and lies in the southern Waikato Region....

tribes (Te ArawaTe ArawaTe Arawa is a confederation of Māori iwi and hapu based in the Rotorua and Bay of Plenty areas of New Zealand, with a population of around 40,000.The history of the Te Arawa people is inextricably linked to the Arawa canoe...

canoe) appear to have placed special emphasis on their descent from a particular canoe migration" (Biggs 1966:451).

Local traditions

Each tribal group, whether tribe or subtribe, maintained its discrete traditional record, which generally concerned "great battles and great men"; these stories were linked together by genealogy, which in Māori tradition is an elaborate art. "In some cases the story is continuous and internally consistent from the migration down to the present. In other cases it is fragmentary and discontinuous earlier than about 1600" (Biggs 1966:453).External links

- First peoples in Māori tradition in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Māori creation traditions in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand