James Kennedy

Encyclopedia

James Kennedy (c. 1408–1465) was a 15th century Bishop of Dunkeld

and Bishop of St. Andrews, who participated in the Council of Florence

and was the last man to govern the diocese of St. Andrews purely as bishop. One of the Gaelic

clan

of Carrick

he became the principal figure in the government of the minority of King James II of Scotland

as well as founder of St Salvator's College, St Andrews

.

He was the third and youngest son of Sir James Kennedy of Dunure, Ayrshire

, and Princess Mary of Scotland, widow of the 1st Earl of Angus

and second daughter of King Robert III of Scotland

. His eldest brother was Gilbert Kennedy, 1st Lord Kennedy

. James was born about 1408, and was sent to the continent to complete his studies in canon law

and theology

.

He was a canon

and sub-deacon

of Dunkeld

until his provision and election to that see

on 1 July 1437, after the death of Domhnall MacNeachdainn

, the last elected bishop who died on his way to obtain consecration

from the Pope

. He received consecration in 1438, the following year.

He set himself to reform abuses, and attended the general council of Florence

, in order to obtain authority from Pope Eugenius IV for his contemplated reforms. Eugenius did not encourage him in his schemes, but gave him the presentation to the abbacy of Scone in commendam

. Bishop James, however, was not Bishop of Dunkeld

for long.

left the bishopric of St Andrews

, the most prestigious Scottish see, vacant, and it was James who was postulated to the vacancy. This occurred while James was at the court of Pope Eugenius IV, busy at Florence

on the historical Council of Florence

. However, before royal letters arrived bearing news of James' election, the Pope had already provided his translation to the see. Formal translation took place on 8 June 1440. He was an active and successful bishop. He celebrated his first mass in his St Andrews Cathedral

on 30 September 1442, and at once resumed his efforts in reform. During the minority of James II

, Kennedy took a leading part in political affairs, and was frequently able to reconcile contending noblemen.

He was made Chancellor of Scotland in May 1444 after the expulsion of Sir William Crichton

, but resigned the office a few weeks later on finding that his duties interfered with his ecclesiastical work. When the schism in the papacy assumed a very critical character, Kennedy undertook a journey to Rome with the intention of promoting a reconciliation. He obtained a safe-conduct through England from Henry VI

, dated 28 May 1446. His efforts were unsuccessful, and he probably soon returned home. Another safe-conduct for himself and others "coming to England", dated 20 May 1455, probably marks the termination of another visit to the continent.

In 1450 he founded St Salvator's College in St. Andrews, endowing it liberally with the teinds of four parishes that had formerly belonged to the bishopric. His foundation was confirmed by Pope Nicholas V

In 1450 he founded St Salvator's College in St. Andrews, endowing it liberally with the teinds of four parishes that had formerly belonged to the bishopric. His foundation was confirmed by Pope Nicholas V

by a bull

dated 27 February 1451, and a few years later some alterations made in the foundation-charter received the approval of Pope Pius II

by bulls dated 13 September and 21 October 1458. Shortly afterwards Kennedy established the Grey Friars monastery in St Andrews. He also built a large vessel called the "Saint Salvator", which was frequently used by royal personages, and regarded as a marvel, until it was wrecked near Bamburgh

while on a voyage to Flanders

in 1472. After the death of James II in 1460, Kennedy was chosen one of the seven regents during the minority of James III

, and to him was committed not only the charge of the kingdom, but the pacification of the nobles associated with him in the government.

. The ruins are still visible.

It is stated by Bishop Lesley

that Kennedy's college, ship, and monument each cost an exceptional amount of money. Kennedy was highly esteemed during his lifetime, both as an ecclesiastic and a politician. Even George Buchanan

says that he excelled all his predecessors and successors in the see, and praises his zeal for reform. Kennedy is said to have left behind him several treatises. The only titles preserved are Historia sui Temporis and Monita Politica.

Bishop of Dunkeld

The Bishop of Dunkeld is the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Dunkeld, one of the largest and more important of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics, whose first recorded bishop is an early 12th century cleric named Cormac...

and Bishop of St. Andrews, who participated in the Council of Florence

Council of Florence

The Council of Florence was an Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church. It began in 1431 in Basel, Switzerland, and became known as the Council of Ferrara after its transfer to Ferrara was decreed by Pope Eugene IV, to convene in 1438...

and was the last man to govern the diocese of St. Andrews purely as bishop. One of the Gaelic

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

clan

Scottish clan

Scottish clans , give a sense of identity and shared descent to people in Scotland and to their relations throughout the world, with a formal structure of Clan Chiefs recognised by the court of the Lord Lyon, King of Arms which acts as an authority concerning matters of heraldry and Coat of Arms...

of Carrick

Carrick, Scotland

Carrick is a former comital district of Scotland which today forms part of South Ayrshire.-History:The word Carrick comes from the Gaelic word Carraig, meaning rock or rocky place. Maybole was the historic capital of Carrick. The county was eventually combined into Ayrshire which was divided...

he became the principal figure in the government of the minority of King James II of Scotland

James II of Scotland

James II reigned as King of Scots from 1437 to his death.He was the son of James I, King of Scots, and Joan Beaufort...

as well as founder of St Salvator's College, St Andrews

St Andrews

St Andrews is a university town and former royal burgh on the east coast of Fife in Scotland. The town is named after Saint Andrew the Apostle.St Andrews has a population of 16,680, making this the fifth largest settlement in Fife....

.

He was the third and youngest son of Sir James Kennedy of Dunure, Ayrshire

Ayrshire

Ayrshire is a registration county, and former administrative county in south-west Scotland, United Kingdom, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine. The town of Troon on the coast has hosted the British Open Golf Championship twice in the...

, and Princess Mary of Scotland, widow of the 1st Earl of Angus

George Douglas, 1st Earl of Angus

George Douglas, 1st Earl of Angus was born at Tantallon Castle, East Lothian, Scotland. The bastard son of William, 1st Earl of Douglas and Margaret Stewart, Dowager Countess of Mar & Countess of Angus and Lady Abernethy in her own right....

and second daughter of King Robert III of Scotland

Robert III of Scotland

Robert III was King of Scots from 1390 to his death. His given name was John Stewart, and he was known primarily as the Earl of Carrick before ascending the throne at age 53...

. His eldest brother was Gilbert Kennedy, 1st Lord Kennedy

Gilbert Kennedy, 1st Lord Kennedy

Gilbert Kennedy of Dunure, 1st Lord Kennedy was a Scottish lord, a son of Sir James Kennedy "the Younger" of Dunure, the Younger, and Lady Mary Stewart, daughter of Robert III, King of the Scots...

. James was born about 1408, and was sent to the continent to complete his studies in canon law

Canon law

Canon law is the body of laws & regulations made or adopted by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of the Christian organization and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church , the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of...

and theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

.

He was a canon

Canon (priest)

A canon is a priest or minister who is a member of certain bodies of the Christian clergy subject to an ecclesiastical rule ....

and sub-deacon

Deacon

Deacon is a ministry in the Christian Church that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions...

of Dunkeld

Dunkeld

Dunkeld is a small town in Strathtay, Perth and Kinross, Scotland. It is about 15 miles north of Perth on the eastern side of the A9 road into the Scottish Highlands and on the opposite side of the Tay from the Victorian village of Birnam. Dunkeld and Birnam share a railway station, on the...

until his provision and election to that see

Episcopal See

An episcopal see is, in the original sense, the official seat of a bishop. This seat, which is also referred to as the bishop's cathedra, is placed in the bishop's principal church, which is therefore called the bishop's cathedral...

on 1 July 1437, after the death of Domhnall MacNeachdainn

Domhnall MacNeachdainn

Domhnall MacNeachdainn was a 15th century Dean and Bishop of Dunkeld. He was the nephew of Robert de Cardeny, Bishop of Dunkeld, by Robert's sister, Mairead . The latter was also the mistress of King Robert II of Scotland. His father was probably a chief of the MacNeachdainn kindred. Domhnall was...

, the last elected bishop who died on his way to obtain consecration

Consecration

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service, usually religious. The word "consecration" literally means "to associate with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different groups...

from the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

. He received consecration in 1438, the following year.

He set himself to reform abuses, and attended the general council of Florence

Council of Florence

The Council of Florence was an Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church. It began in 1431 in Basel, Switzerland, and became known as the Council of Ferrara after its transfer to Ferrara was decreed by Pope Eugene IV, to convene in 1438...

, in order to obtain authority from Pope Eugenius IV for his contemplated reforms. Eugenius did not encourage him in his schemes, but gave him the presentation to the abbacy of Scone in commendam

In Commendam

In canon law, commendam was a form of transferring an ecclesiastical benefice in trust to the custody of a patron...

. Bishop James, however, was not Bishop of Dunkeld

Bishop of Dunkeld

The Bishop of Dunkeld is the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Dunkeld, one of the largest and more important of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics, whose first recorded bishop is an early 12th century cleric named Cormac...

for long.

Bishop of St Andrews

The death of Henry WardlawHenry Wardlaw

Henry Wardlaw was a Scottish church leader, Bishop of St Andrews and founder of the University of St Andrews.He was a son of II Laird of Wilton Henry Wardlaw who was b. 1318, and a nephew of Walter Wardlaw Henry Wardlaw (died 6 April 1440) was a Scottish church leader, Bishop of St Andrews and...

left the bishopric of St Andrews

St Andrews

St Andrews is a university town and former royal burgh on the east coast of Fife in Scotland. The town is named after Saint Andrew the Apostle.St Andrews has a population of 16,680, making this the fifth largest settlement in Fife....

, the most prestigious Scottish see, vacant, and it was James who was postulated to the vacancy. This occurred while James was at the court of Pope Eugenius IV, busy at Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

on the historical Council of Florence

Council of Florence

The Council of Florence was an Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church. It began in 1431 in Basel, Switzerland, and became known as the Council of Ferrara after its transfer to Ferrara was decreed by Pope Eugene IV, to convene in 1438...

. However, before royal letters arrived bearing news of James' election, the Pope had already provided his translation to the see. Formal translation took place on 8 June 1440. He was an active and successful bishop. He celebrated his first mass in his St Andrews Cathedral

St Andrew's Cathedral, St Andrews

The Cathedral of St Andrew is a historical church in St Andrews, Fife, Scotland, which was the seat of the Bishops of St Andrews from its foundation in 1158 until it fell into disuse after the Reformation. It is currently a ruined monument in the custody of Historic Scotland...

on 30 September 1442, and at once resumed his efforts in reform. During the minority of James II

James II of Scotland

James II reigned as King of Scots from 1437 to his death.He was the son of James I, King of Scots, and Joan Beaufort...

, Kennedy took a leading part in political affairs, and was frequently able to reconcile contending noblemen.

He was made Chancellor of Scotland in May 1444 after the expulsion of Sir William Crichton

William Crichton, 1st Lord Crichton

William Crichton, 1st Lord Crichton of Sanquhar was an important political figure in Scotland.He held various positions within the court of James I. At the death of James I, William Crichton was Sheriff of Edinburgh, Keeper of Edinburgh Castle, and Master of the King’s household...

, but resigned the office a few weeks later on finding that his duties interfered with his ecclesiastical work. When the schism in the papacy assumed a very critical character, Kennedy undertook a journey to Rome with the intention of promoting a reconciliation. He obtained a safe-conduct through England from Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

, dated 28 May 1446. His efforts were unsuccessful, and he probably soon returned home. Another safe-conduct for himself and others "coming to England", dated 20 May 1455, probably marks the termination of another visit to the continent.

Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V , born Tommaso Parentucelli, was Pope from March 6, 1447 to his death in 1455.-Biography:He was born at Sarzana, Liguria, where his father was a physician...

by a bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

dated 27 February 1451, and a few years later some alterations made in the foundation-charter received the approval of Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II, born Enea Silvio Piccolomini was Pope from August 19, 1458 until his death in 1464. Pius II was born at Corsignano in the Sienese territory of a noble but decayed family...

by bulls dated 13 September and 21 October 1458. Shortly afterwards Kennedy established the Grey Friars monastery in St Andrews. He also built a large vessel called the "Saint Salvator", which was frequently used by royal personages, and regarded as a marvel, until it was wrecked near Bamburgh

Bamburgh

Bamburgh is a large village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It has a population of 454.It is notable for two reasons: the imposing Bamburgh Castle, overlooking the beach, seat of the former Kings of Northumbria, and at present owned by the Armstrong family ; and its...

while on a voyage to Flanders

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

in 1472. After the death of James II in 1460, Kennedy was chosen one of the seven regents during the minority of James III

James III of Scotland

James III was King of Scots from 1460 to 1488. James was an unpopular and ineffective monarch owing to an unwillingness to administer justice fairly, a policy of pursuing alliance with the Kingdom of England, and a disastrous relationship with nearly all his extended family.His reputation as the...

, and to him was committed not only the charge of the kingdom, but the pacification of the nobles associated with him in the government.

Death and legacy

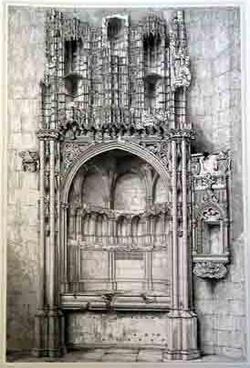

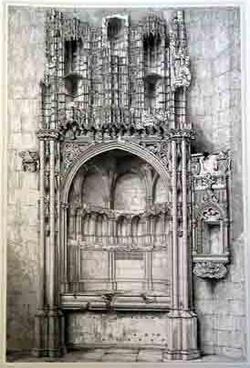

He died on 24 May 1465. The date is usually given as 1466, but a charter belonging to the abbey of Arbroath, dated 13 July 1465, speaks of him as lately deceased, and of his see as vacant. Kennedy was buried in a magnificent tomb which he had caused to be built in St Salvator's Chapel. He had, it is believed, procured the design and materials from ItalyItaly

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. The ruins are still visible.

It is stated by Bishop Lesley

John Lesley

John Lesley was a Scottish Roman Catholic bishop and historian. His father was Gavin Lesley, rector of Kingussie, Badenoch.-Early career:...

that Kennedy's college, ship, and monument each cost an exceptional amount of money. Kennedy was highly esteemed during his lifetime, both as an ecclesiastic and a politician. Even George Buchanan

George Buchanan (humanist)

George Buchanan was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. He was part of the Monarchomach movement.-Early life:...

says that he excelled all his predecessors and successors in the see, and praises his zeal for reform. Kennedy is said to have left behind him several treatises. The only titles preserved are Historia sui Temporis and Monita Politica.

DNB sources

- This article incorporates text from the Dictionary of National BiographyDictionary of National BiographyThe Dictionary of National Biography is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published from 1885...

, 1891. It cites the following sources:- Reg. Mag. Sig. Scot., 1424–1513

- Cal. Documents relating to Scotland, vol. iv.

- Thomas RymerThomas RymerThomas Rymer , English historiographer royal, was the younger son of Ralph Rymer, lord of the manor of Brafferton in Yorkshire, described by Clarendon as possessed of a good estate, who was executed for his share in the Presbyterian rising of 1663.-Early life and education:Thomas Rymer was born at...

's Fœdera - KeithRobert Keith (historian)Robert Keith was a Scottish Episcopal bishop and historian.-Life:Born at Uras in Kincardineshire, Scotland, on 7 February 1681, he was the second son of Alexander Keith and Marjory Keith . He was educated at Marischal College, Aberdeen between 1695 and 1699; graduating with an A.M...

's Scottish Bishops

Further reading

- James Kennedy has been one of the most written about prelates in medieval Britain. The following are some works available but not used for the article:

- Dunlop, A. I., The Life and Times of James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews, (St Andrews, 1950)

- Macdougall, Norman, "Bishop James Kennedy of St Andrews: a reassessment of his political career", in Norman Macdougall (ed.), Church, Politics and Society: Scotland, 1408–1929, (1983), pp. 1–22

- Macdougall, Norman, "Kennedy, James (c.1408–1465)", in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 , accessed 23 Feb 2007