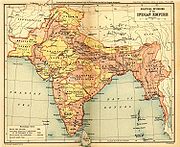

Indian famine of 1899–1900

Encyclopedia

Central Provinces and Berar

The Central Provinces and Berar was a province of British India. The province comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Its capital was Nagpur. The Central Provinces was formed in...

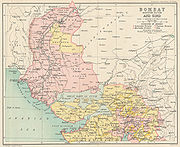

, the Bombay Presidency

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

, the minor province of Ajmer-Merwara

Ajmer-Merwara

Ajmer-Merwara is a former province of British India in the historical Ajmer region. The territory of the province was ceded to the British by Daulat Rao Sindhia by a treaty on June 25, 1818....

, and the Hissar District of the Punjab

Punjab region

The Punjab , also spelled Panjab |water]]s"), is a geographical region straddling the border between Pakistan and India which includes Punjab province in Pakistan and the states of the Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh and some northern parts of the National Capital Territory of Delhi...

; it also caused great distress in the princely states of the Rajputana Agency

Rajputana Agency

The Rajputana Agency was a political office of the British Indian Empire dealing with a collection of native states in India , under the political charge of an Agent reporting directly to the Governor-General of India and residing at Mount Abu in the Aravalli Range...

, the Central India Agency

Central India Agency

The Central India Agency was a political office of the British Indian Empire, which covered the northern half of present-day Madhya Pradesh state. The Central India Agency was made up entirely of princely states, which were under native rulers...

, Hyderabad

Hyderabad State

-After Indian independence :When India gained independence in 1947 and Pakistan came into existence in 1947, the British left the local rulers of the princely states the choice of whether to join one of the new dominions or to remain independent...

and the Kathiawar Agency

Kathiawar Agency

The Kathiawar Agency, on the Kathiawar peninsula in the western part of the Indian subcontinent, was a political unit of some 200 small princely states under the suzerainty of the Bombay Presidency of British India. Soon after India's independence in 1947, all but one of them acceded to the new...

. In addition, small areas of the Bengal Presidency

Bengal Presidency

The Bengal Presidency originally comprising east and west Bengal, was a colonial region of the British Empire in South-Asia and beyond it. It comprised areas which are now within Bangladesh, and the present day Indian States of West Bengal, Assam, Bihar, Meghalaya, Orissa and Tripura.Penang and...

, the Madras Presidency

Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency , officially the Presidency of Fort St. George and also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision of British India...

and the North-Western Provinces

North-Western Provinces

The North-Western Provinces was an administrative region in British India which succeeded the Ceded and Conquered Provinces and existed in one form or another from 1836 until 1902, when it became the Agra Province within the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh .-Area:The province included all...

were acutely afflicted by the famine.

The population in many areas had barely recovered from the famine of 1896–1897. As in that famine, this one too was preceded by a drought. The Meteorological Office of India in its report of 1900, stated, "The mean average rainfall of India is 45 inches (1,143 mm). In no previous famine year has it been in greater defect than 5 inches (127 mm). But in 1899 the defect exceeded 11 inches." There were also large crop failures in the rest of India and, as a result, inter-regional trade could not be relied upon to stabilise food prices.

The resulting mortality was high. In the Deccan, an estimated 166,000 people died, and in the entire Bombay Presidency

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

a total of 462,000. In the Presidency, the famine of 1899–1900 had the highest mortality—at 37.9 deaths per 1000—among all famines and scarcities there between 1876–77 and 1918–19. Overall, in British areas alone, approximately 1,000,000 individuals died of starvation or accompanying disease; in addition, as a result of acute shortage of fodder, cattle in the millions perished. Other estimates vary between 1 million and 4.5 million deaths.

Course

In the Central Provinces and BerarCentral Provinces and Berar

The Central Provinces and Berar was a province of British India. The province comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered much of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Its capital was Nagpur. The Central Provinces was formed in...

, an area that had suffered extreme distress during the famine of 1896–1897, the year 1898 had been favourable agriculturally, as was the first half of 1899; however, after the failure of the summer monsoon of 1899, a second catastrophe began soon afterwards. There was a rapid rise of prices and the autumn kharif harvest failed completely. After public criticism of the famine relief effort in the previous famine, this time an improved famine relief effort was organised; by July 1900, one-fifth of the province's population was on some form of famine relief. The summer monsoon of 1900 produced moderately abundant rainfall, and by autumn, agricultural work had begun; most famine-relief works were consequently closed by December 1900. Overall, the famine of 1899–1900 was less severe in this region than the famine of two years before. In the Bombay Presidency

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

, the reverse was the case: the famine of 1899–1900, which affected a population of 12 million, was more acute, especially so in the Kathiawar Agency

Kathiawar Agency

The Kathiawar Agency, on the Kathiawar peninsula in the western part of the Indian subcontinent, was a political unit of some 200 small princely states under the suzerainty of the Bombay Presidency of British India. Soon after India's independence in 1947, all but one of them acceded to the new...

. The recovery from the famine in the Presidency was also very slow.

Epidemics

Both 1896 and 1899 were El Niño years—years in which the monsoon rainfall was considerably less than average. The year following the El Niño, also called a Niño+1 year, has historically been recognised to have not only higher than average rainfall, but also a much higher probability of malariaMalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

epidemics. For example in the Punjab province

Punjab region

The Punjab , also spelled Panjab |water]]s"), is a geographical region straddling the border between Pakistan and India which includes Punjab province in Pakistan and the states of the Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh and some northern parts of the National Capital Territory of Delhi...

of British India, of the 77 years from 1867 to 1943, there were 21 El Niño years, 11 of whose Niño+1 years produced malaria epidemics; in contrast, there were only six malaria epidemics in the remaining 56 non-El Niño years. "Fever years follow famine years" had become a popular saying in the Punjab long before Sir Ronald Ross

Ronald Ross

Sir Ronald Ross KCB FRS was a British doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on malaria. He was the first Indian-born person to win a Nobel Prize...

, working in the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta, showed in 1898 that the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum is a protozoan parasite, one of the species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans. It is transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria caused by this species is the most dangerous form of malaria, with the highest rates of complications and mortality...

, is transmitted by mosquitoes. It had also been noted, by R. Christophers in 1911, that years in which the monsoon was abundant, but which had not been preceded by famine years, were not likely to be epidemic years. These observations had prompted some scholars to theorise that the increased malaria mortality in a post-famine year was the result of lowered resistance to malaria caused by the malnutrition. However, it is now thought likely that the dry famine years decreased human exposure to mosquitoes, which thrive in stagnant water, and consequently to Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum

Plasmodium falciparum is a protozoan parasite, one of the species of Plasmodium that cause malaria in humans. It is transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito. Malaria caused by this species is the most dangerous form of malaria, with the highest rates of complications and mortality...

; the decreased exposure resulted in lowered immunity among the population, thereby making subsequent exposures all the more devastating.

In 1900, a Niño+1 year, malaria epidemics, occurred in the Punjab, Central Provinces and Berar, and the Bombay Presidency, with devastating results. In the Central Provinces and Berar, the death rates were initially quite low. The Report on the Famine in the Central Provinces in 1899–1900 noted the "extreme healthiness of the first four months of the famine, September to December 1899." The low mortality indicated the absence of malaria in 1899; however, by the summer of 1900, an epidemic of cholera had begun, and soon the monsoon rains of 1900 brought on the malaria epidemic. Consequently, the death rate peaked between August and September 1900, a full year after the famine began. In the Bombay Presidency, the same pattern of pre-monsoon cholera followed by post-monsoon malaria in 1900 was repeated. The Report on the Famine in the Bombay Presidency, 1899–1902 pronounced the epidemic to be "unprecedented," noting that "It attacked all classes and was by no means confined to the people who had been on relief works ..."

Usury

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

as well as in the British outpost of Ajmer-Merwara

Ajmer-Merwara

Ajmer-Merwara is a former province of British India in the historical Ajmer region. The territory of the province was ceded to the British by Daulat Rao Sindhia by a treaty on June 25, 1818....

farther north. The middle decades of the 19th century saw not only the implementation of a new system of land revenue and land rights in these areas, but also the establishment of new civil law. Under the new land rights system, peasants could be dispossessed of their land if they failed to pay the land-revenue (or land-tax) in a timely fashion. The British, however, continued to rely on local Baniya usurers, or Sahukars, to supply credit to the peasants. The imposition of the new system of civil law, however, meant that the peasants could be exploited by the sahukars, who were often able, through the new civil courts, to acquire title-deeds to a peasant's land for non-payment of debt.

The mid-19th century was also a time of predominance of the economic theories of Adam Smith

Adam Smith

Adam Smith was a Scottish social philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations...

and David Ricardo

David Ricardo

David Ricardo was an English political economist, often credited with systematising economics, and was one of the most influential of the classical economists, along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill. He was also a member of Parliament, businessman, financier and speculator,...

, and the principle of laissez-faire

Laissez-faire

In economics, laissez-faire describes an environment in which transactions between private parties are free from state intervention, including restrictive regulations, taxes, tariffs and enforced monopolies....

was subscribed to by many colonial administrators; the British, consequently, declined to interfere in the markets. This meant that the Baniya sahukars could resort to hoarding during times of scarcity, driving up the price of food grain, and profiteering in the aftermath. All this occurred in Western India during the famine of 1899–1900.

In Khaira District

Kheda district

Kheda district is one of the 26 districts of Gujarat state in western India. Kheda city is the administrative headquarters of the district.-History:...

in present-day Gujarat, many peasants were forced to hand over their lands to the sahukars as security for meager loans that not only didn't granted them much relief, but that they later couldn't repay on account of exorbitant interest. The sahukars were to foreclose on these loans in the years after the famine; in the princely state of Baroda, for example, the recorded land-transfers were to jump from an average of 13,000 per year during the decade of the 1890s, to over 65,000 during the year 1902–1903.

The sahukars, in their effort to drive up prices, were even able to export grain out of areas of scarcity using the faster means of transport that came in with British rule. Here again the colonial administrators declined to intervene, even though they themselves often disapproved of the practice. This happened, for example, in the Panchmahals—one of the worst famine-afflicted areas in 1900—where a railway line had been built in the 1890s. A British deputy district collector

District collector

The District Collector is the district head of administration of the bureaucracy in a state of India. Though he/she is appointed and is under general supervision of the state government, he/she has to be a member of the elite IAS recruited by the Central Government...

recorded in his report, "The merchants first cleared large profits by exporting their surplus stocks of grain at the commencement of the famine, and, later on by importing maize

Maize

Maize known in many English-speaking countries as corn or mielie/mealie, is a grain domesticated by indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica in prehistoric times. The leafy stalk produces ears which contain seeds called kernels. Though technically a grain, maize kernels are used in cooking as a vegetable...

from Cawnpore and Bombay and rice from Calcutta and Rangoon." He went on to record that the sahukars were building new houses for themselves from these windfall profits. The blatant profiteering

Profiteering

Profiteering may relate to:* Profiteering * War profiteering...

, however, led to grain riots in the Panchmahals by Bhil

Bhil

Bhils are primarily an Adivasi people of Central India. Bhils are also settled in the Tharparkar District of Sindh, Pakistan. They speak the Bhil languages, a subgroup of the Western Zone of the Indo-Aryan languages....

tribals, and grain riots became a feature of other British-ruled areas during times of famine. This contrasted markedly with the princely states, where the authorities often did intervene. For example, in Jodhpur State, a famine-stricken area in Rajputana

Rajputana Agency

The Rajputana Agency was a political office of the British Indian Empire dealing with a collection of native states in India , under the political charge of an Agent reporting directly to the Governor-General of India and residing at Mount Abu in the Aravalli Range...

, in August 1899, the state officials set up a shop to sell grain at cost price, forcing the Baniya merchants to eventually bring down their prices.

Economic changes

The Indian famine of 1899–1900 was the last of the all-India famines. (The war-time Bengal famine of 1943 was confined mainly to Bengal and some neighbouring regions.) The famine proved to be a watershed between the overwhelmingly subsistence agricultureSubsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture is self-sufficiency farming in which the farmers focus on growing enough food to feed their families. The typical subsistence farm has a range of crops and animals needed by the family to eat and clothe themselves during the year. Planting decisions are made with an eye...

economy of 19th century India and a more diversified economy of the 20th century, which, by offering other forms of employment, created less agricultural disruption (and, consequently, less mortality) during times of scarcity.

The construction of Indian railways

Indian Railways

Indian Railways , abbreviated as IR , is a departmental undertaking of Government of India, which owns and operates most of India's rail transport. It is overseen by the Ministry of Railways of the Government of India....

between 1860 and 1920, and the opportunities thereby offered for greater profit in other markets, allowed farmers to accumulate assets that could then be drawn upon during times of scarcity. By the early 20th century, many farmers in the Bombay presidency

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

were growing a portion of their crop for export. Wheat, both food

Subsistence agriculture

Subsistence agriculture is self-sufficiency farming in which the farmers focus on growing enough food to feed their families. The typical subsistence farm has a range of crops and animals needed by the family to eat and clothe themselves during the year. Planting decisions are made with an eye...

and cash crop

Cash crop

In agriculture, a cash crop is a crop which is grown for profit.The term is used to differentiate from subsistence crops, which are those fed to the producer's own livestock or grown as food for the producer's family...

, saw increased production and export during this time; in addition, cotton and oil-seeds were also exported. The railways also brought in food, whenever expected scarcities began to drive up food prices.

There were other changes in the economy as well: a construction boom in the Bombay presidency

Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

, in both the private and public sectors, during the first two decades of the 20th century, created a demand for unskilled labour. There was greater demand for agricultural labour as well, brought on both by the planting of more labour-intensive crops and the expansion of the cropped area in the presidency. Real agricultural wages, for example, increased sharply after 1900. All these provided farmers with greater insurance against famine. During times of drought, they could now seek seasonal non-agricultural employment; alternatively, they could temporarily move to areas where there was no drought and work as agricultural wage labourers.

According to , "Famines in the nineteenth century tended to be characterized by some degree of aimless wandering of agriculturalists after their own supplies of food had run out." Since these migrations caused further depletion among individuals who were already malnourished and since new areas exposed them to unfamiliar disease pathogens, the attendant mortality was high. In the 20th century, however, these temporary migrations became more purposive, especially from regions (in the Bombay Presidency) that were highly drought prone. A greater availability of jobs throughout the presidency and a better organised system of famine relief offered by the provincial government allowed most men in afflicted villages to migrate elsewhere as soon as their own meager harvest had been collected. McAlpin further notes:

Villages are reported to have housed only women and children, and old men in some years of crop failure. Those left behind could tend the livestock, live off the short harvest, and expect that the government would step in to provide relief—including grain sales or gratuitous relief—if necessary. With the beginning of the next agricultural season the men would return to the village with some earnings from their outside employment which could be used to resume agricultural operations. In most cases, the livestock would also have been preserved through the actions of women and children.

Mortalilty

In the Deccan, an estimated 166,000 people died, and in the entire Bombay PresidencyBombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency was a province of British India. It was established in the 17th century as a trading post for the English East India Company, but later grew to encompass much of western and central India, as well as parts of post-partition Pakistan and the Arabian Peninsula.At its greatest...

a total of 462,000. In the Presidency, the famine of 1899–1900 had the highest mortality—at 37.9 deaths per 1000—among all famines and scarcities there between 1876–77 and 1918–19. According to the Imperial Gazetteer of India, overall, in British areas alone, approximately 1,000,000 individuals died of starvation or accompanying disease; in addition, as a result of acute shortage of fodder, cattle in the millions perished in the famine. According to author David Fieldhouse

David Kenneth Fieldhouse

David Kenneth Fieldhouse, FBA is a prominent historian of the British Empire who between 1981 and 1992 held the Vere Harmsworth Professorship of Imperial and Naval History at the University of Cambridge...

, over 1 million people may have died during the famine of 1899–1900; according to anthropologist Brian Fagan, up to four and a half million people may have died during the famine .

The following table gives the varying estimates of total famine related deaths between 1896 and 1902 (including both the 1899-1900 famine and the famine of 1896–1897).

| Estimate of famine deaths (in millions) between 1896 and 1902 | Done by | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | The Lancet The Lancet The Lancet is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal. It is one of the world's best known, oldest, and most respected general medical journals... |

The Lancet The Lancet The Lancet is a weekly peer-reviewed general medical journal. It is one of the world's best known, oldest, and most respected general medical journals... (Issue dt. 16 May 1901) |

| 8.4 | Arup Maharatna Ronald E. Seavoy |

The Demography of Famines: An Indian Historical Perspective, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996 Famine in Peasant Societies (Contributions in Economics and Economic History), New York: Greenwood Press, 1986 |

| 6.1 | Cambridge Economic History of India | The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 1983 (pp. 530–31) |

The Lancet's estimates were criticised by writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn, arguing that it was based on a mistake of the population increase in India from 1891-1901.

See also

- Indian famine of 1896–1897

- Famines, Epidemics, and Public Health in the British RajFamines, Epidemics, and Public Health in the British RajAmong the common features of famines, epidemics, and public health in the British Raj during the 19th century were:* There was no aggregate food shortage in India, although there were localized crop failures in the affected areas...

- Timeline of major famines in India during British rule (1765 to 1947)Timeline of major famines in India during British rule (1765 to 1947)This is a timeline of major famines on the Indian subcontinent during the years of British rule in India from 1765 to 1947. The famines included here occurred both in the princely states and British India This is a timeline of major famines on the Indian subcontinent during the years of British...

- Company rule in IndiaCompany rule in IndiaCompany rule in India refers to the rule or dominion of the British East India Company on the Indian subcontinent...

- Famine in IndiaFamine in IndiaFamine has been a recurrent feature of life in the Indian sub-continental countries of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and reached its numerically deadliest peak in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Historical and legendary evidence names some 90 famines in 2,500 years of history. There...

- Drought in IndiaDrought in IndiaDrought in India has resulted in tens of millions of deaths over the course of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Indian agriculture is heavily dependent on the climate of India: a favorable southwest summer monsoon is critical in securing water for irrigating Indian crops...