History of polymerase chain reaction

Encyclopedia

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, inventor, and astronomer. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity. Among his advances in physics are the foundations of hydrostatics, statics and an...

"Eureka!"

Eureka (word)

"Eureka" is an interjection used to celebrate a discovery, a transliteration of a word attributed to Archimedes.-Etymology:The word comes from ancient Greek εὕρηκα heúrēka "I have found ", which is the 1st person singular perfect indicative active of the verb heuriskō "I find"...

moment, or as an example of cooperative teamwork between disparate researchers. A list of some of the events before, during, and after its development:

Prelude

- On April 25, 1953 James D. WatsonJames D. WatsonJames Dewey Watson is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick...

and Francis CrickFrancis CrickFrancis Harry Compton Crick OM FRS was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist, and most noted for being one of two co-discoverers of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, together with James D. Watson...

published "a radically different structure" for DNADNADeoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

, thereby founding the field of Molecular GeneticsMolecular geneticsMolecular genetics is the field of biology and genetics that studies the structure and function of genes at a molecular level. The field studies how the genes are transferred from generation to generation. Molecular genetics employs the methods of genetics and molecular biology...

. Their structural modelMolecular structure of Nucleic AcidsThe "Molecular structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid" was an article published by James D. Watson and Francis Crick in the scientific journal Nature in its 171st volume on pages 737–738 . It was the first publication which described the discovery of the double helix...

featured two strands of complementaryComplementarity (molecular biology)In molecular biology, complementarity is a property of double-stranded nucleic acids such as DNA, as well as DNA:RNA duplexes. Each strand is complementary to the other in that the base pairs between them are non-covalently connected via two or three hydrogen bonds...

base-pairedBase pairIn molecular biology and genetics, the linking between two nitrogenous bases on opposite complementary DNA or certain types of RNA strands that are connected via hydrogen bonds is called a base pair...

DNA, running in opposite directions as a double helix. They concluded their report saying that "It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material". For this insight they were awarded the Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in Physiology or MedicineThe Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

in 1962.

- Starting in the mid 1950s, Arthur KornbergArthur KornbergArthur Kornberg was an American biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 for his discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid " together with Dr. Severo Ochoa of New York University...

began to study the mechanism of DNA replicationDNA replicationDNA replication is a biological process that occurs in all living organisms and copies their DNA; it is the basis for biological inheritance. The process starts with one double-stranded DNA molecule and produces two identical copies of the molecule...

. By 1957 he has identified the first DNA polymeraseDNA polymeraseA DNA polymerase is an enzyme that helps catalyze in the polymerization of deoxyribonucleotides into a DNA strand. DNA polymerases are best known for their feedback role in DNA replication, in which the polymerase "reads" an intact DNA strand as a template and uses it to synthesize the new strand....

. The enzyme was limited, creating DNA in just one direction and requiring an existing primerPrimer (molecular biology)A primer is a strand of nucleic acid that serves as a starting point for DNA synthesis. They are required for DNA replication because the enzymes that catalyze this process, DNA polymerases, can only add new nucleotides to an existing strand of DNA...

to initiate copying of the template strand. Overall, the DNA replication process is surprisingly complex, requiring separate proteins to open the DNA helix, to keepSingle-strand binding proteinSingle-strand binding protein, also known as SSB or SSBP, binds to single stranded regions of DNA to prevent premature annealing. The strands have a natural tendency to revert to the duplex form, but SSB binds to the single strands, keeping them separate and allowing the DNA replication machinery...

it open, to create primersPrimaseDNA primase is an enzyme involved in the replication of DNA.Primase catalyzes the synthesis of a short RNA segment called a primer complementary to a ssDNA template...

, to synthesizeDNA polymerase III holoenzymeDNA polymerase III holoenzyme is the primary enzyme complex involved in prokaryotic DNA replication. It was discovered by Thomas Kornberg and Malcolm Gefter in 1970. The complex has high processivity DNA polymerase III holoenzyme is the primary enzyme complex involved in prokaryotic DNA...

new DNA, to removeDNA polymerase IDNA Polymerase I is an enzyme that participates in the process of DNA replication in prokaryotes. It is composed of 928 amino acids, and is an example of a processive enzyme - it can sequentially catalyze multiple polymerisations. Discovered by Arthur Kornberg in 1956, it was the first known...

the primers, and to tieDNA ligaseIn molecular biology, DNA ligase is a specific type of enzyme, a ligase, that repairs single-stranded discontinuities in double stranded DNA molecules, in simple words strands that have double-strand break . Purified DNA ligase is used in gene cloning to join DNA molecules together...

the pieces all together. Kornberg was awarded the Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in Physiology or MedicineThe Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

in 1959.

- In the early 1960s H. Gobind Khorana made significant advances in the elucidation of the Genetic CodeGenetic codeThe genetic code is the set of rules by which information encoded in genetic material is translated into proteins by living cells....

. Afterwards, he initiated a large project to totally synthesizeGene synthesisArtificial gene synthesis is the process of synthesizing a gene in vitro without the need for initial template DNA samples. The main method is currently by oligonucleotide synthesis from digital genetic sequences and subsequent annealing of the resultant fragments...

a functional human geneGeneA gene is a molecular unit of heredity of a living organism. It is a name given to some stretches of DNA and RNA that code for a type of protein or for an RNA chain that has a function in the organism. Living beings depend on genes, as they specify all proteins and functional RNA chains...

. To achieve this, Khorana pioneered many of the techniques needed to make and use syntheticOligonucleotide synthesisOligonucleotide synthesis is the chemical synthesis of relatively short fragments of nucleic acids with defined chemical structure . The technique is extremely useful in current laboratory practice because it provides a rapid and inexpensive access to custom-made oligonucleotides of the desired...

DNA oligonucleotideOligonucleotideAn oligonucleotide is a short nucleic acid polymer, typically with fifty or fewer bases. Although they can be formed by bond cleavage of longer segments, they are now more commonly synthesized, in a sequence-specific manner, from individual nucleoside phosphoramidites...

s. Sequence-specific oligonucleotides were used both as building blocks for the gene, and as primers and templates for DNA polymerase. In 1968 Khorana was awarded the Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in Physiology or MedicineThe Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine administered by the Nobel Foundation, is awarded once a year for outstanding discoveries in the field of life science and medicine. It is one of five Nobel Prizes established in 1895 by Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, in his will...

for his work on the Genetic Code.

- In 1969 Thomas D. BrockThomas D. BrockThomas Dale Brock is an American microbiologist known for his discovery of hyperthermophiles living in hot springs at Yellowstone National Park....

reported the isolation of a new species of bacterium from a hot springHot springA hot spring is a spring that is produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater from the Earth's crust. There are geothermal hot springs in many locations all over the crust of the earth.-Definitions:...

in Yellowstone National ParkYellowstone National ParkYellowstone National Park, established by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872, is a national park located primarily in the U.S. state of Wyoming, although it also extends into Montana and Idaho...

. 'Thermus aquaticusThermus aquaticusThermus aquaticus is a species of bacterium that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the Deinococcus-Thermus group...

(Taq), became a standard source of enzymes able to withstand higher temperatures than those from E. ColiEscherichia coliEscherichia coli is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms . Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in humans, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls...

.

- In 1970 Klenow reported a modified version of DNA Polymerase I from E. coli. Treatment with a protease removed the 'forward' nuclease activity of this enzyme. The overall activity of the resulting Klenow fragmentKlenow fragmentright|thumb|450px|Functional domains in the Klenow Fragment and DNA Polymerase I .The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from E. coli is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin...

is therefore biased towards the synthesis of DNA, rather than its degradation.

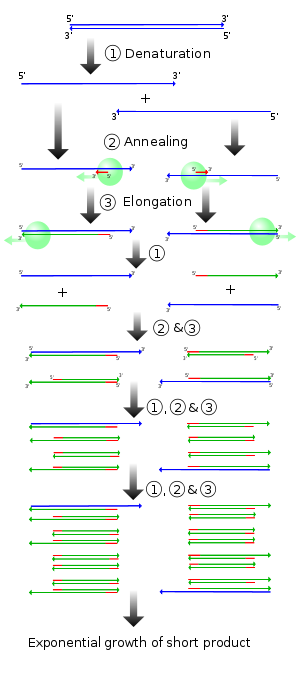

- By 1971 researchers in Khorana's project, concerned over their yields of DNA, began looking at "repair synthesis" - an artificial system of primers and templates that allows DNA polymerase to copy segments of the gene they are synthesizing. Although similar to PCR in using repeated applications of DNA polymerase, the process they usually describe employs just a single primer-template complex, and therefore would not lead to the exponential amplification seen in PCR.

- Circa 1971 Kjell Kleppe, a researcher in Khorana's lab, envisioned a process very similar to PCR. At the end of a paper on the earlier technique, he described how a two-primer system might lead to replication of a specific segment of DNA:

- "... one would hope to obtain two structures, each containing the full length of the template strand appropriately complexed

- with the primer. DNA polymerase will be added to complete the process of repair replication. Two molecules of the original

- duplex should result. The whole cycle could be repeated, there being added every time a fresh dose of the enzyme."

- No results are shown there, and the mention of unpublished experiments in another paper may (or may not) refer to the two-primer replication system. (These early precursors to PCR were carefully scrutinized in a patent lawsuit, and are discussed in Mullis' chapters in.)

- Also in 1971, Cetus CorporationCetus CorporationCetus Corporation was one of the first biotechnology companies. It was established in Berkeley, California in 1971, but conducted most of its operations in nearby Emeryville. Before merging with another company in 1991, it developed several significant pharmaceutical drugs as well as a...

was founded in Berkeley, CaliforniaBerkeley, CaliforniaBerkeley is a city on the east shore of the San Francisco Bay in Northern California, United States. Its neighbors to the south are the cities of Oakland and Emeryville. To the north is the city of Albany and the unincorporated community of Kensington...

by Ronald Cape, Peter Farley, and Donald Glaser. Initially the company screened for microorganisms capable of producing components used in the manufacture of food, chemicals, vaccines, or pharmaceuticals. After moving to nearby EmeryvilleEmeryville, CaliforniaEmeryville is a small city located in Alameda County, California, in the United States. It is located in a corridor between the cities of Berkeley and Oakland, extending to the shore of San Francisco Bay. Its proximity to San Francisco, the Bay Bridge, the University of California, Berkeley, and...

, they began projects involving the new biotechnologyGenetic engineeringGenetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

industry, primarily the cloningRecombinant DNARecombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

and expressionGene expressionGene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein coding genes such as ribosomal RNA , transfer RNA or small nuclear RNA genes, the product is a functional RNA...

of human genes, but also the development of diagnostic tests for genetic mutations.

- In 1976 a DNA polymeraseTaq polymerasethumb|228px|right|Structure of Taq DNA polymerase bound to a DNA octamerTaq polymerase is a thermostable DNA polymerase named after the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus from which it was originally isolated by Thomas D. Brock in 1965...

was isolated from T. aquaticusThermus aquaticusThermus aquaticus is a species of bacterium that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the Deinococcus-Thermus group...

. It was found to retain its activity at temperatures above 75°C.

- In 1977 Frederick SangerFrederick SangerFrederick Sanger, OM, CH, CBE, FRS is an English biochemist and a two-time Nobel laureate in chemistry, the only person to have been so. In 1958 he was awarded a Nobel prize in chemistry "for his work on the structure of proteins, especially that of insulin"...

reported a method for determining the sequence of DNA. The technique employed an oligonucleotide primerPrimer (molecular biology)A primer is a strand of nucleic acid that serves as a starting point for DNA synthesis. They are required for DNA replication because the enzymes that catalyze this process, DNA polymerases, can only add new nucleotides to an existing strand of DNA...

, DNA polymerase, and modified nucleotide precursors that block further extension of the primer in sequence-dependent manner. For this innovation he was awarded the Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

in 1980.

By 1980 all of the components needed to perform PCR amplification were known to the scientific community. The use of DNA polymerase to extend oligonucleotide primers was a common procedure in DNA sequencing and the production of cDNA

Complementary DNA

In genetics, complementary DNA is DNA synthesized from a messenger RNA template in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase and the enzyme DNA polymerase. cDNA is often used to clone eukaryotic genes in prokaryotes...

for cloning

Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA molecules are DNA sequences that result from the use of laboratory methods to bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be found in biological organisms...

and expression

Gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein coding genes such as ribosomal RNA , transfer RNA or small nuclear RNA genes, the product is a functional RNA...

. The use of DNA polymerase for nick translation

Nick translation

Nick translation was developed in 1977 by Rigby and Paul Berg. It is a tagging technique in molecular biology in which DNA Polymerase I is used to replace some of the nucleotides of a DNA sequence with their labeled analogues, creating a tagged DNA sequence which can be used as a probe in...

was the most common method used to label DNA probes

Hybridization probe

In molecular biology, a hybridization probe is a fragment of DNA or RNA of variable length , which is used in DNA or RNA samples to detect the presence of nucleotide sequences that are complementary to the sequence in the probe...

for Southern blot

Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method routinely used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detection by probe hybridization. The method is named...

ting.

history of PCR

♣♣ In 1979 Cetus CorporationCetus Corporation

Cetus Corporation was one of the first biotechnology companies. It was established in Berkeley, California in 1971, but conducted most of its operations in nearby Emeryville. Before merging with another company in 1991, it developed several significant pharmaceutical drugs as well as a...

hired Kary Mullis

Kary Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis is a Nobel Prize winning American biochemist, author, and lecturer. In recognition of his improvement of the polymerase chain reaction technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and earned the Japan Prize in the same year. The process was first...

to synthesize oligonucleotides for various research and development projects throughout the company. These oligos were used as probes for screening cloned genes, as primers for DNA sequencing and cDNA synthesis, and as building blocks for gene construction. Originally synthesizing these oligos by hand, Mullis later evaluated early prototypes for automated synthesizers.

♣♣ By May 1983 Mullis synthesized oligo probes for a project at Cetus to analyze a Sickle Cell Anemia mutation. Hearing of problems with their work, Mullis proposed an alternative technique based on Sanger's DNA sequencing method. Realizing the difficulty in making the Sanger method specific to a single location in the genome, Mullis then modified the idea to add a second primer on the opposite strand. Repeated applications of polymerase could lead to a chain reaction of replication for a specific segment of the genome - PCR.

♣♣ Later in 1983 Mullis began to test his idea. His first experiment did not involve thermal cycling - he hoped that the polymerase could perform continued replication on its own. Later experiments that year included repeated thermal cycling, and targeted small segments of a cloned gene. Mullis considered these experiments a success, but could not convince other researchers.

♣♣♣ In June 1984 Cetus held its annual meeting in Monterey, California

Monterey, California

The City of Monterey in Monterey County is located on Monterey Bay along the Pacific coast in Central California. Monterey lies at an elevation of 26 feet above sea level. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 27,810. Monterey is of historical importance because it was the capital of...

. Its scientists and consultants presented their results, and considered future projects. Mullis presented a poster on the production of oligonucleotides by his laboratory, and presented some of the results from his experiments with PCR. Only Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg

Joshua Lederberg ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was just 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and...

, a Cetus consultant, showed any interest. Later at the meeting, Mullis was involved in a physical altercation with another Cetus researcher, over a dispute unrelated to PCR. The other scientist left the company, and Mullis was removed as head of the oligo synthesis lab.

Development

- In September 1984 Tom White, VPVice presidentA vice president is an officer in government or business who is below a president in rank. The name comes from the Latin vice meaning 'in place of'. In some countries, the vice president is called the deputy president...

of Research at Cetus (and a close friend), pressured Mullis to take his idea to the group developing the genetic mutation assay. Together, they spent the following months designing experiments that could convincingly show that PCR is working on genomic DNA. Unfortunately, the expected amplification product was not visible in agarose gel electrophoresis, leading to confusion as to whether the reaction had any specificity to the targeted region.

- In November 1984 the amplification products were analyzed by Southern blotSouthern blotA Southern blot is a method routinely used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detection by probe hybridization. The method is named...

ting, which clearly demonstrating increasing amount of the expected 110 bpBase pairIn molecular biology and genetics, the linking between two nitrogenous bases on opposite complementary DNA or certain types of RNA strands that are connected via hydrogen bonds is called a base pair...

DNA product. Having the first visible signal, the researchers began optimizing the process. Later, the amplified products were cloned and sequenced, showing that only a small fraction of the amplified DNA is the desired target, and that the Klenow fragmentKlenow fragmentright|thumb|450px|Functional domains in the Klenow Fragment and DNA Polymerase I .The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from E. coli is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin...

then being used only rarely incorporates incorrect nucleotides during replication.

Exposition

- As per normal industrial practice, the results were first used to apply for patentPatentA patent is a form of intellectual property. It consists of a set of exclusive rights granted by a sovereign state to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for the public disclosure of an invention....

s. Mullis applied for a patent covering the basic idea of PCR and many potential applications, and was asked by the PTOUnited States Patent and Trademark OfficeThe United States Patent and Trademark Office is an agency in the United States Department of Commerce that issues patents to inventors and businesses for their inventions, and trademark registration for product and intellectual property identification.The USPTO is based in Alexandria, Virginia,...

to include more results. On March 28, 1985 the entire development group (including Mullis) filed an application that is more focused on the analysis of the Sickle Cell Anemia mutation via PCR and Oligomer restrictionOligomer restrictionOligomer Restriction is a procedure to detect an altered DNA sequence in a genome. A labeled oligonucleotide probe is hybridized to a target DNA, and then treated with a restriction enzyme. If the probe exactly matches the target, the restriction enzyme will cleave the probe, changing its size...

. After modification, both patents were approved on July 28, 1987.

- In the spring of 1985 the development group began to apply the PCR technique to other targets. Primers and probes were designed for a variable segment of the Human leukocyte antigenHuman leukocyte antigenThe human leukocyte antigen system is the name of the major histocompatibility complex in humans. The super locus contains a large number of genes related to immune system function in humans. This group of genes resides on chromosome 6, and encodes cell-surface antigen-presenting proteins and...

DQαHLA-DQA1Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ alpha 1, also known as HLA-DQA1, is a human gene present on short arm of chromosome 6 and also denotes the genetic locus which contains this gene...

gene. This reaction was much more specific than that for the β-hemoglobin target - the expected PCR product is directly visible on agarose gel electrophoresis. The amplification products from various sources were also cloned and sequenced, the first determination of new alleles by PCR. At this same time the original Oligomer Restriction assay technique was replaced with the more general Allele specific oligonucleotideAllele specific oligonucleotideAn allele-specific oligonucleotide is a short piece of synthetic DNA complementary to the sequence of a variable target DNA. It acts as a probe for the presence of the target in a Southern blot assay or, more commonly, in the simpler Dot blot assay...

method.

- Also early in 1985, the group began using a thermostable DNA polymerase (the enzymeKlenow fragmentright|thumb|450px|Functional domains in the Klenow Fragment and DNA Polymerase I .The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from E. coli is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin...

used in the original reaction is destroyed at each heating step). At the timeonly two had been described, from TaqThermus aquaticusThermus aquaticus is a species of bacterium that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the Deinococcus-Thermus group...

and BstBacillus stearothermophilusBacillus stearothermophilus is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium and a member of the division Firmicutes. The bacteria is a thermophile and is widely distributed in soil, hot springs, ocean sediment, and is a cause of spoilage in food products. It will grow within a temperature range of 30-75...

. The report on Taq polymerase was more detailed, so it was chosen for testing. The Bst polymerase was later found to be unsuitable for PCR. That summer Mullis attempted to isolate the enzyme, and a group outside of Cetus was contracted to make it, all without success. In the Fall of 1985 Susanne Stoffel and David Gelfand at Cetus succeed in making the polymerase, and it was immediately found by Randy Saiki to support the PCR process.

- With patents submitted, work proceeded to report PCR to the general scientific community. An abstract for a American Society of Human GeneticsAmerican Society of Human GeneticsThe American Society of Human Genetics , founded in 1948, is the primary professional membership organization for specialists in human genetics worldwide. As of 2009, the organization had approximately 8,000 members...

meeting in Salt Lake City was submitted in April 1985, and the first announcement of PCR was made there by Saiki in October. Two publications were planned - an 'idea' paper from Mullis, and an 'application' paper from the entire development group. Mullis submitted his manuscript to the journal NatureNature (journal)Nature, first published on 4 November 1869, is ranked the world's most cited interdisciplinary scientific journal by the Science Edition of the 2010 Journal Citation Reports...

, which rejected it for not including results. The other paper, mainly describing the OROligomer restrictionOligomer Restriction is a procedure to detect an altered DNA sequence in a genome. A labeled oligonucleotide probe is hybridized to a target DNA, and then treated with a restriction enzyme. If the probe exactly matches the target, the restriction enzyme will cleave the probe, changing its size...

analysis assay, was submitted to ScienceScience (journal)Science is the academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and is one of the world's top scientific journals....

on September 20, 1985 and was accepted in November. After the rejection of Mullis' report in December, details on the PCR process were hastily added to the second paper, which appears on December 20, 1985.

- In May 1986 Mullis presented PCR at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium, and published a modified version of his original 'idea' manuscript much later. The first non-Cetus report using PCR was submitted on September 5, 1986, indicating how quickly other laboratories began implementing the technique. The Cetus development group published their detailed sequence analysis of PCR products on September 8, 1986, and their use of ASOAllele specific oligonucleotideAn allele-specific oligonucleotide is a short piece of synthetic DNA complementary to the sequence of a variable target DNA. It acts as a probe for the presence of the target in a Southern blot assay or, more commonly, in the simpler Dot blot assay...

probes on November 13, 1986.

- The use of Taq polymerase in PCR was announced by Henry Erlich at a meetingInternational Congress of Human GeneticsThe International Congress of Human Genetics is the foremost meeting of the international human genetics community. The first Congress was held in 1956 in Copenhagen, and has met every five years since then...

in Berlin on September 20, 1986, submitted for publication in October 1987, and was published early the next year'. The patent for PCR with Taq polymerase was filed on June 17, 1987, and is issued on October 23, 1990.

Variation

- In December 1985 a joint venture between Cetus and Perkin-ElmerPerkinElmerPerkinElmer, Inc. is an American multinational technology corporation, focused in the business areas of human and environmental health, including environmental analysis, food and consumer product safety, medical imaging, drug discovery, diagnostics, biotechnology, industrial applications, and life...

was established to develop instruments and reagents for PCR. Complex Thermal CyclersThermal cyclerThe thermal cycler is a laboratory apparatus used to amplify segments of DNA via the polymerase chain reaction process. The device has a thermal block with holes where tubes holding the PCR reaction mixtures can be inserted...

were constructed to perform the Klenow-based amplifications, but never marketed. Simpler machines for Taq-based PCR were developed, and on November 19, 1987 a press release announces the commercial availability of the "PCR-1000 Thermal Cycler" and "AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase".

- In the Spring of 1985 John Sninsky at Cetus began to use PCR for the difficult task of measuring the amount of HIV circulating in blood. A viable test was announced on April 11, 1986, and published in May 1987. Donated blood could then be screened for the virus, and the effect of antiviral drugs directly monitored.

- In 1985 Norm Arnheim, also a member of the development team, concluded his sabbatical at Cetus and assumed an academic position at USCUniversity of Southern CaliforniaThe University of Southern California is a private, not-for-profit, nonsectarian, research university located in Los Angeles, California, United States. USC was founded in 1880, making it California's oldest private research university...

. He began to investigate the use of PCR to amplifiy samples containing just a single copy of the target sequence. By 1989 his lab developed mutiplex-PCR on single sperm to directly analyze the products of meiotic recombination. These single-copy amplifications, which had first been run during the characterization of Taq polymerase, became vital to the study of ancient DNAAncient DNAAncient DNA is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. It can be also loosely described as any DNA recovered from biological samples that have not been preserved specifically for later DNA analyses...

, as well as the genetic typing of preimplanted embryos.

- In 1986 Edward Blake, a forensics scientist working in the Cetus building, collaborated with Bruce Budowle (of the FBI) and Cetus researchers to apply PCR to the analysis of criminal evidence. A panel of DNA samples from old cases was collected and coded, and was analyzed blind by Saiki using the HLA DQα assay. When the code was broken, all of the evidence and perpetrators matched. Blake used the technique almost immediately in "Pennsylvania v. Pestinikas", the first use of PCR in a criminal case. This DQα test is developed by Cetus as one of their "Ampli-Type" kits, and became part of early protocols for the testing of forensic evidence, such as in the O. J. Simpson murder caseO. J. Simpson murder caseThe O. J. Simpson murder case was a criminal trial held in Los Angeles County, California Superior Court from January 29 to October 3, 1995. Former American football star and actor O. J...

.

- By 1989 Alec JeffreysAlec JeffreysSir Alec John Jeffreys, FRS is a British geneticist, who developed techniques for DNA fingerprinting and DNA profiling which are now used all over the world in forensic science to assist police detective work, and also to resolve paternity and immigration disputes...

, who had earlier developed and applied the first DNA Fingerprinting tests, used PCR to increase their sensitivity. With further modification, the amplification of highly polymorphic VNTRVariable number tandem repeatA Variable Number Tandem Repeat is a location in a genome where a short nucleotide sequence is organized as a tandem repeat. These can be found on many chromosomes, and often show variations in length between individuals. Each variant acts as an inherited allele, allowing them to be used for...

loci became the standard protocol for National DNA DatabaseNational DNA databaseA national DNA database is a government database of DNA profiles which can be used by law enforcement agencies to identify suspects of crimes....

s such as CODISCombined DNA Index SystemThe Combined DNA Index System is a DNA database funded by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation . It is a computer system that stores DNA profiles created by federal, state, and local crime laboratories in the United States, with the ability to search the database to assist in the...

.

- In 1987 Russ Higuchi succeeded in amplifying DNA from a human hair. This work expanded to develop methods for the amplification of DNA from highly degraded samples, such as from Ancient DNAAncient DNAAncient DNA is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. It can be also loosely described as any DNA recovered from biological samples that have not been preserved specifically for later DNA analyses...

and in forensicForensicsForensic science is the application of a broad spectrum of sciences to answer questions of interest to a legal system. This may be in relation to a crime or a civil action...

evidence.

Coda

- On December 22, 1989 the journal ScienceScience (journal)Science is the academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and is one of the world's top scientific journals....

awarded Taq Polymerase (and PCR) its first "Molecule of the Year". The 'Taq PCR' paper became for several years the most citedCitation indexA citation index is a kind of bibliographic database, an index of citations between publications, allowing the user to easily establish which later documents cite which earlier documents. The first citation indices were legal citators such as Shepard's Citations...

publication in biology.

- After the publication of the first PCR paper, the United States Government sent a stern letter to Randy Saiki, admonishing him for publishing a report on "chain reactions"Nuclear chain reactionA nuclear chain reaction occurs when one nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more nuclear reactions, thus leading to a self-propagating number of these reactions. The specific nuclear reaction may be the fission of heavy isotopes or the fusion of light isotopes...

without the required prior review and approval by the U.S. Department of Energy. Cetus responded, explaining the differences between PCR and the atomic bombNuclear weaponA nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission or a combination of fission and fusion. Both reactions release vast quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter. The first fission bomb test released the same amount...

.

- On July 23, 1991 Cetus announced that its sale to the neighboring biotechnology company ChironChiron CorporationChiron Corporation was a multinational biotechnology firm based in Emeryville, California that was acquired by Novartis International AG on April 20, 2006. It had offices and facilities in eighteen countries on five continents. Chiron's business and research was in three main areas:...

. As part of the sale, rights to the PCR patents were sold for USD $300 million to Hoffman-La Roche (who in 1989 had bought limited rights to PCR). Many of the Cetus PCR researchers moved to the Roche subsidiary, Roche Molecular SystemsRoche DiagnosticsRoche Diagnostics Division is a subsidiary of Hoffmann-La Roche which manufactures equipment and reagents for research and medical diagnostic applications. Internally, it is organized into five major business areas: Roche Applied Science, Roche Professional Diagnostics, Roche Diabetes Care, Roche...

.

- On October 13, 1993 Kary Mullis, who had left Cetus in 1986, was awarded the Nobel Prize in ChemistryNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

. On the morning of his acceptance speech, he was nearly arrested by Swedish authorities for the "inappropriate use of a laser pointer".