Thermus aquaticus

Encyclopedia

Thermus aquaticus is a species of bacterium that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the Deinococcus-Thermus

group. It is the source of the heat-resistant enzyme Taq DNA polymerase

, one of the most important enzymes in molecular biology

because of its use in the polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) DNA amplification technique.

and Hudson Freeze of Indiana University

reported a new species

of thermophilic

bacterium which they named Thermus aquaticus. The bacterium was first discovered in the Lower Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park

, near the major geyser

s Great Fountain Geyser

and White Dome Geyser

, and has since been found in similar thermal habitats around the world.

is a chemotroph

- it performs chemosynthesis

to obtain food. However, since its range of temperature overlaps somewhat with that of the photosynthetic cyanobacteria that share its ideal environment, it is sometimes found living jointly with its neighbors, obtaining energy for growth from their photosynthesis.

, a public repository. Other scientists, including those at Cetus, obtained it from there. As the commercial potential of Taq polymerase became apparent in the 1990s, the National Park Service

labeled its use as the "Great Taq Rip-off". Researchers working in National Parks are now required to sign "benefits sharing" agreements that would send a portion of later profits back to the Park Service.

Deinococcus-Thermus

The Deinococcus-Thermus are a small group of bacteria composed of cocci highly resistant to environmental hazards.There are two main groups.* The Deinococcales include two families, with three genera, Deinococcus and Truepera, the former with several species that are resistant to radiation; they...

group. It is the source of the heat-resistant enzyme Taq DNA polymerase

Taq polymerase

thumb|228px|right|Structure of Taq DNA polymerase bound to a DNA octamerTaq polymerase is a thermostable DNA polymerase named after the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus from which it was originally isolated by Thomas D. Brock in 1965...

, one of the most important enzymes in molecular biology

Molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that deals with the molecular basis of biological activity. This field overlaps with other areas of biology and chemistry, particularly genetics and biochemistry...

because of its use in the polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction is a scientific technique in molecular biology to amplify a single or a few copies of a piece of DNA across several orders of magnitude, generating thousands to millions of copies of a particular DNA sequence....

(PCR) DNA amplification technique.

History

When studies of biological organisms in hot springs began in the 1960s, scientists thought that the life of thermophilic bacteria could not be sustained in temperatures above about 55° Celsius (131° Fahrenheit). Soon, however, it was discovered that many bacteria in different springs not only survived, but also thrived in higher temperatures. In 1969, Thomas D. BrockThomas D. Brock

Thomas Dale Brock is an American microbiologist known for his discovery of hyperthermophiles living in hot springs at Yellowstone National Park....

and Hudson Freeze of Indiana University

Indiana University Bloomington

Indiana University Bloomington is a public research university located in Bloomington, Indiana, in the United States. IU Bloomington is the flagship campus of the Indiana University system. Being the flagship campus, IU Bloomington is often referred to simply as IU or Indiana...

reported a new species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

of thermophilic

Thermophile

A thermophile is an organism — a type of extremophile — that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between 45 and 122 °C . Many thermophiles are archaea...

bacterium which they named Thermus aquaticus. The bacterium was first discovered in the Lower Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park, established by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1872, is a national park located primarily in the U.S. state of Wyoming, although it also extends into Montana and Idaho...

, near the major geyser

Geyser

A geyser is a spring characterized by intermittent discharge of water ejected turbulently and accompanied by a vapour phase . The word geyser comes from Geysir, the name of an erupting spring at Haukadalur, Iceland; that name, in turn, comes from the Icelandic verb geysa, "to gush", the verb...

s Great Fountain Geyser

Great Fountain Geyser

The Great Fountain Geyser is a fountain-type geyser located in the Firehole Lake area of Lower Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. It is the only predicted geyser in the Lower Geyser Basin.-Eruption:...

and White Dome Geyser

White Dome Geyser

White Dome Geyser is a geyser located in the Lower Geyser Basin in Yellowstone National Park in the United States.White Dome is a conspicuous cone-type geyser located only a few feet from Firehole Lake Drive, and accordingly, seen by many visitors to the park as they wait for eruptions of nearby...

, and has since been found in similar thermal habitats around the world.

Biology

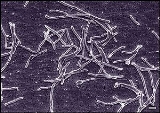

It thrives at 70°C (160°F), but can survive at temperatures of 50°C to 80°C (120°F to 175°F). This bacteriumBacteria

Bacteria are a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria have a wide range of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals...

is a chemotroph

Chemotroph

Chemotrophs are organisms that obtain energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic or inorganic . The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phototrophs, which utilize solar energy...

- it performs chemosynthesis

Chemosynthesis

In biochemistry, chemosynthesis is the biological conversion of one or more carbon molecules and nutrients into organic matter using the oxidation of inorganic molecules or methane as a source of energy, rather than sunlight, as in photosynthesis...

to obtain food. However, since its range of temperature overlaps somewhat with that of the photosynthetic cyanobacteria that share its ideal environment, it is sometimes found living jointly with its neighbors, obtaining energy for growth from their photosynthesis.

Enzymes from T. aquaticus

T. aquaticus has become famous as a source of thermostable enzymes, particularly the "Taq" DNA polymerase, as described below.- Aldolase

- Studies of this extreme thermophilic bacterium that could be grown in cell cultureCell cultureCell culture is the complex process by which cells are grown under controlled conditions. In practice, the term "cell culture" has come to refer to the culturing of cells derived from singlecellular eukaryotes, especially animal cells. However, there are also cultures of plants, fungi and microbes,...

was initially centered on attempts to understand how proteinProteinProteins are biochemical compounds consisting of one or more polypeptides typically folded into a globular or fibrous form, facilitating a biological function. A polypeptide is a single linear polymer chain of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of...

enzymes (which normally inactivate at high temperature) can function at high temperature in thermophileThermophileA thermophile is an organism — a type of extremophile — that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between 45 and 122 °C . Many thermophiles are archaea...

s. In 1970, Freeze and Brock published an article describing a thermostable aldolaseGlycolysisGlycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose C6H12O6, into pyruvate, CH3COCOO− + H+...

enzyme from T. aquaticus.

- RNA polymeraseRNA polymeraseRNA polymerase is an enzyme that produces RNA. In cells, RNAP is needed for constructing RNA chains from DNA genes as templates, a process called transcription. RNA polymerase enzymes are essential to life and are found in all organisms and many viruses...

- The first polymerasePolymeraseA polymerase is an enzyme whose central function is associated with polymers of nucleic acids such as RNA and DNA.The primary function of a polymerase is the polymerization of new DNA or RNA against an existing DNA or RNA template in the processes of replication and transcription...

enzyme isolated from T. aquaticus in 1974, was a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, used in the process of transcriptionTranscription (genetics)Transcription is the process of creating a complementary RNA copy of a sequence of DNA. Both RNA and DNA are nucleic acids, which use base pairs of nucleotides as a complementary language that can be converted back and forth from DNA to RNA by the action of the correct enzymes...

.

- Taq I restriction enzyme

- Most molecular biologists probably became aware of T. aquaticus in the late 1970s or early 1980s because of the isolation of useful restriction endonucleasesRestriction enzymeA Restriction Enzyme is an enzyme that cuts double-stranded DNA at specific recognition nucleotide sequences known as restriction sites. Such enzymes, found in bacteria and archaea, are thought to have evolved to provide a defense mechanism against invading viruses...

from this organism. Use of the term "Taq" to refer to Thermus aquaticus arose at this time from the convention of giving restriction enzymes short names, such as Sal and Hin, derived from the genus and species of the source organisms.

- DNA polymeraseDNA polymeraseA DNA polymerase is an enzyme that helps catalyze in the polymerization of deoxyribonucleotides into a DNA strand. DNA polymerases are best known for their feedback role in DNA replication, in which the polymerase "reads" an intact DNA strand as a template and uses it to synthesize the new strand....

("Taq pol")

- DNA polymerase was first isolated from T. aquaticus in 1976. The first advantage found for this thermostable (temperature optimum 80°C) DNA polymerase was that it could be isolated in a purer form (free of other enzyme contaminants) than could the DNA polymerase from other sources. Later, Kary MullisKary MullisKary Banks Mullis is a Nobel Prize winning American biochemist, author, and lecturer. In recognition of his improvement of the polymerase chain reaction technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and earned the Japan Prize in the same year. The process was first...

and other investigators at Cetus CorporationCetus CorporationCetus Corporation was one of the first biotechnology companies. It was established in Berkeley, California in 1971, but conducted most of its operations in nearby Emeryville. Before merging with another company in 1991, it developed several significant pharmaceutical drugs as well as a...

discovered this enzyme could be used in the polymerase chain reactionPolymerase chain reactionThe polymerase chain reaction is a scientific technique in molecular biology to amplify a single or a few copies of a piece of DNA across several orders of magnitude, generating thousands to millions of copies of a particular DNA sequence....

(PCR) process for amplifying short segments of DNADNADeoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

, eliminating the need to add enzyme after every cycle of thermal denaturation of the DNA. The enzyme was also clonedMolecular cloningMolecular cloning refers to a set of experimental methods in molecular biology that are used to assemble recombinant DNA molecules and to direct their replication within host organisms...

, sequencedDNA sequencingDNA sequencing includes several methods and technologies that are used for determining the order of the nucleotide bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—in a molecule of DNA....

, modified (to produce the shorter 'Stoffel fragment'), and produced in large quantities for commercial sale. In 1989 ScienceScience (journal)Science is the academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and is one of the world's top scientific journals....

magazine named Taq polymerase as its first "Molecule of the Year". In 1993, Dr. Mullis was awarded the Nobel PrizeNobel Prize in ChemistryThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outstanding contributions in chemistry, physics, literature,...

for his work with PCR.

- Other enzymes

- The high optimum temperature for T. aquaticus allows researchers to study reactions under conditions for which other enzymes lose activity. Other enzymes isolated from this organism include DNA ligaseDNA ligaseIn molecular biology, DNA ligase is a specific type of enzyme, a ligase, that repairs single-stranded discontinuities in double stranded DNA molecules, in simple words strands that have double-strand break . Purified DNA ligase is used in gene cloning to join DNA molecules together...

, alkaline phosphataseAlkaline phosphataseAlkaline phosphatase is a hydrolase enzyme responsible for removing phosphate groups from many types of molecules, including nucleotides, proteins, and alkaloids. The process of removing the phosphate group is called dephosphorylation...

, NADH oxidaseOxidaseAn oxidase is any enzyme that catalyzes an oxidation-reduction reaction involving molecular oxygen as the electron acceptor. In these reactions, oxygen is reduced to water or hydrogen peroxide ....

, isocitrate dehydrogenaseIsocitrate dehydrogenaseIsocitrate dehydrogenase and , also known as IDH, is an enzyme that participates in the citric acid cycle. It catalyzes the third step of the cycle: the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate, producing alpha-ketoglutarate and CO2 while converting NAD+ to NADH...

, amylomaltaseMaltaseMaltase is an enzyme that breaks down the disaccharide maltose. Maltase is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of the disaccharide maltose to the simple sugar glucose. This enzyme is found in plants, bacteria, and yeast. Then there is what is called Acid maltase deficiency...

, and fructose 1,6-disphosphate-dependent L-lactate dehydrogenaseLactate dehydrogenaseLactate dehydrogenase is an enzyme present in a wide variety of organisms, including plants and animals.Lactate dehydrogenases exist in four distinct enzyme classes. Two of them are cytochrome c-dependent enzymes, each acting on either D-lactate or L-lactate...

.

Controversy

The commercial use of enzymes from T. aquaticus has not been without controversy. After Dr. Brock's studies, samples of the organism were deposited in the American Type Culture CollectionAmerican Type Culture Collection

The American Type Culture Collection is a private, not-for-profit biological resource center whose mission focuses on the acquisition, authentication, production, preservation, development and distribution of standard reference microorganisms, cell lines and other materials for research in the...

, a public repository. Other scientists, including those at Cetus, obtained it from there. As the commercial potential of Taq polymerase became apparent in the 1990s, the National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

labeled its use as the "Great Taq Rip-off". Researchers working in National Parks are now required to sign "benefits sharing" agreements that would send a portion of later profits back to the Park Service.