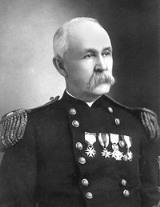

George Miller Sternberg

Encyclopedia

Brigadier General

George Miller Sternberg (June 8, 1838 – November 3, 1915) was a U.S. Army

physician

who is considered the first U.S.

bacteriologist, having written Manual of Bacteriology (1892). After he survived typhoid

and yellow fever

, Sternberg documented the cause of malaria

(1881), discovered the cause of lobar pneumonia

(1881), and confirmed the roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis

and typhoid fever

(1886).

As the 18th U.S. Army Surgeon General

, from 1893 to 1902, Sternberg led commissions to control typhoid and yellow fever, with Walter Reed

. Sternberg also oversaw the establishment of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (1901). The pioneering German

bacteriologist Robert Koch

honored Sternberg with the sobriquet

, "Father of American Bacteriology

".

George Sternberg was born at Hartwick Seminary

George Sternberg was born at Hartwick Seminary

, Otsego County, New York

, where he spent most of his childhood. His father, Levi Sternberg, a Lutheran clergyman who later became principal of Hartwick Seminary

, was descended from a German family from the Palatinate, which had settled in the Schoharie Valley

in the early years of the 18th century. His mother, Margaret Levering (Miller) Sternberg, was the daughter of George B. Miller, also a Lutheran clergyman and professor of theology

at the seminary, which was a Lutheran school. He was the eldest child of a large family and he was given adult responsibilities from an early age. He interrupted his studies at the seminary with a year of work in a bookstore in Cooperstown

and three years of teaching in nearby rural schools. During his last year at Hartwick he was an instructor in mathematics

, chemistry

, and natural philosophy

. He was at the same time pursuing the study of medicine

with Horace Lathrop of Cooperstown. For his formal medical training he went first to Buffalo

, and later to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York (M.D.

degree, 1860). After graduation he settled in Elizabeth, New Jersey

to practice, remaining there until the outbreak of the Civil War.

in the U.S. Army, and on July 21 of the same year was captured at the First Battle of Bull Run

, while serving with General George Sykes

' division. He managed to escape and soon joined his command in the defense of Washington. He later participated in the Peninsular campaign and saw service in the battles of Gaines' Mill

and Malvern Hill

. During this campaign he contracted typhoid fever

while at Harrison's Landing and was sent north on a transport. During the remainder of the war he performed hospital duty, mostly at Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island, and at Cleveland, Ohio

. On March 13, 1865, he was given the Brevet

s of captain and major

for faithful and meritorious service.

The years following the war followed the pattern of frequent moves typical of junior medical officers of the day. He married Louisa Russell, daughter of Robert Russell of Cooperstown, on October 19, 1865 and took his bride to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, from where he was soon transferred to Fort Harker

, near Ellsworth

in Kansas

. Louisa did not accompany him to the latter post, but joined him in 1867 just prior to an outbreak of cholera

. She was one of the first civilians to develop the disease which killed her within a few hours on July 15 and soon claimed a toll of about 75 people at the fort.

Indians along the upper Arkansas River

in Indian Territory and in western Kansas. Besides his military duties, Sternberg was also interested in fossils and began collecting leaf imprints from the nearby Dakota Sandstone Formation

. Some of his specimens went back East where they were studied by the famous paleobotanist, Leo Lesquereux

.

Sternberg also collected vertebrate fossils, including shark teeth, fish remains and mosasaur bones, from the Smoky Hill Chalk

and Pierre Shale formations in western Kansas, and sent the specimens back to Washington, D.C., where they were eventually curated in the United States National Museum (Smithsonian Institution

). There they were studied and later described in publications by Joseph Leidy

. The type specimen of the giant Late Cretaceous

fish, Xiphactinus audax, was collected by Dr. Sternberg. His work was also credited by Edward D. Cope and Samuel W. Williston. Sternberg was also responsible for getting his younger brother, Charles H. Sternberg, started in paleontology

. Charles would later credit his older brother for getting many other paleontologists of the day interested in the fossil resources of Kansas.

Sternberg served at Fort Riley until July 1870, when be was ordered to Governors Island, New York. In the meantime, he had remarried on September 1, 1869, at Indianapolis, Indiana

, to Martha L. Pattison, a daughter of Thomas T. N. Pattison of that city.

, Florida, Sternberg had frequent contacts with yellow fever

patients, and at the latter post, he contracted the disease himself. He had earlier noted the efficiency of moving inhabitants out of an infested environment and successfully applied that method to the Barrancas garrison. At about this time, Sternberg published two articles in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal ("An Inquiry into the Modus Operandi of the Yellow Fever Poison," July 1875, and "A Study of the Natural History of Yellow Fever," March 1877) which gained him status as an authority on yellow fever. While convalescing from his bout with the disease in 1877 be was ordered to Fort Walla Walla

, Washington, and later that year he participated in a campaign against the Nez Perce Indians. The spent his spare hours in study and experimentation which laid a foundation for his later work. In 1870 he perfected an anemometer

and patented an automatic heat regulator which later saw wide use.

On December 1, 1875, Sternberg was promoted major, and in April 1879, he was ordered to Washington, D. C., and detailed with the 1880 Havana Yellow Fever Commission. His medical colleagues on the Commission were Doctors Stanfard Chaille of New Orleans and Juan Guiteras

of Havana

. Sternberg was assigned to work on the problems relating to the nature and natural history of the disease and especially to its etiology

(origins). This involved the microscopical examination of blood and tissues in which he was one of the first to employ the newly discovered process of photomicrography. He developed high efficiency in its use. In the course of this work, he spent three months in Havana closely associated with Dr. Carlos Finlay

, the main proponent of the theory of mosquito transmission of yellow fever.

. Sternberg was soon sent to New Orleans to investigate the conflicting discoveries of Plasmodium malariae

by Alphonse Laveran, and of Bacillus malariae by Edwin Klebs

and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli. His report (1881) declared that the Bacillus malariae had no part in the causation of malaria. The same year — simultaneously with Louis Pasteur

— he announced the discovery of the pneumococcus

, eventually recognized as the pathogenic agent of lobar pneumonia

. He was the first in the United States to demonstrate the Plasmodium

organism as cause of malaria (1885) and the to confirm the causitive roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis and typhoid fever (1886). He was the first scientist to produce photomicrographs of the tubercule bacillus

. He was also the earliest American pioneer in the related field of disinfection in which he began with experiments (1878) with putrefactive bacteria

. This work was continued in Washington and in the laboratories of Johns Hopkins Hospital

in Baltimore

, under the auspices of the American Public Health Association

. For his essay "Disinfection and Individual Prophylaxis against Infectious Diseases" (1886), later translated into several languages, he was awarded the Lomb Prize. He oversaw creation the US Army enlisted hospital corps ("medics") in 1887.

During the Hamburg

cholera epidemic of 1892 he was detailed for duty with the New York quarantine station as a consultant on disinfection as applied to ships, their personnel, and cargo. Although some cases of the disease reached United States shores, none developed within the country.

on May 30, 1893, with promotion to the grade of brigadier general.

Sternberg's nine year tenure (1893–1902) as Surgeon General coincided with immense professional progress in the field of bacteriology as well as the occurrence of the Spanish-American War

. He was responsible for the 1893 establishment of the Army Medical School

(precursor of today's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

), the organization of a contract dental service, the creation of the tuberculosis hospital at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, and of a special surgical hospital at Washington Barracks. The equipment of the medical school included laboratories of chemistry and bacteriology, and a liberal-minded policy was adopted in the supply of laboratory supplies to the larger military hospitals. With the Spanish-American War and its epidemic of typhoid fever, the problem of field hospitalization was confronted with fair success. (He was subjected to much criticism for conditions at these hospitals, but made little reply.) Sternberg created the Typhoid Fever Board (1898), consisting of Majors Walter Reed

, Victor C. Vaughan, and Edward O. Shakespeare, which established the facts of contact infection and fly carriage of the disease. In 1900 he organized the Yellow Fever Commission, headed by Reed, which ultimately fixed the transmission of yellow fever upon a particular species of mosquito. (These became celebrated as the “Walter Reed Boards”). On his recommendation the first tropical disease board was also established in Manila (January 1900) where it continued for about the next two years. In 1901, Sternberg oversaw the establishment of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

Sternberg was retired on account of age on June 8, 1902, and devoted the later years of his life to social welfare activities in Washington, particularly to the sanitary improvement of dwellings and to the care of tuberculous patients. Sternberg died at his home in Washington, on November 3, 1915.

is the inscription:

Along with Pasteur and Koch, Sternberg is credited with first bringing the fundamental principles and techniques of the new science of bacteriology within the reach of the average physician.

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

George Miller Sternberg (June 8, 1838 – November 3, 1915) was a U.S. Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

physician

Physician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

who is considered the first U.S.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

bacteriologist, having written Manual of Bacteriology (1892). After he survived typhoid

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

and yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

, Sternberg documented the cause of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

(1881), discovered the cause of lobar pneumonia

Lobar pneumonia

Lobar pneumonia is a form of pneumonia that affects a large and continuous area of the lobe of a lung.It is one of the two anatomic classifications of pneumonia .- Symptoms :...

(1881), and confirmed the roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

and typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

(1886).

As the 18th U.S. Army Surgeon General

Surgeons General of the United States Army

The Surgeon General of the United States Army is the senior-most officer of the U.S. Army Medical Department . By policy, the Surgeon General serves as Commanding General, U.S. Army Medical Command as well as head of the AMEDD...

, from 1893 to 1902, Sternberg led commissions to control typhoid and yellow fever, with Walter Reed

Walter Reed

Major Walter Reed, M.D., was a U.S. Army physician who in 1900 led the team that postulated and confirmed the theory that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species, rather than by direct contact...

. Sternberg also oversaw the establishment of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (1901). The pioneering German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

bacteriologist Robert Koch

Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch was a German physician. He became famous for isolating Bacillus anthracis , the Tuberculosis bacillus and the Vibrio cholerae and for his development of Koch's postulates....

honored Sternberg with the sobriquet

Sobriquet

A sobriquet is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another. It is usually a familiar name, distinct from a pseudonym assumed as a disguise, but a nickname which is familiar enough such that it can be used in place of a real name without the need of explanation...

, "Father of American Bacteriology

Bacteriology

Bacteriology is the study of bacteria. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classification, and characterization of bacterial species...

".

Youth and education

Hartwick, New York

Hartwick is a town located in Otsego County, New York, USA. As of the 2000 census, the town had a population of 2,203.Town of Hartwick is located in the middle of the county, southwest of Village of Cooperstown....

, Otsego County, New York

Otsego County, New York

Otsego County is a county located in the U.S. state of New York. The 2010 population was 62,259. The county seat is Cooperstown. The name Otsego is from a Mohawk word meaning "place of the rock."-History:...

, where he spent most of his childhood. His father, Levi Sternberg, a Lutheran clergyman who later became principal of Hartwick Seminary

Hartwick College

Hartwick College is a non-denominational, private, four-year liberal arts and sciences college located in Oneonta, New York, in the United States. The institution was founded as Hartwick Seminary in 1797 through the will of John Christopher Hartwick, and is now known as Hartwick College...

, was descended from a German family from the Palatinate, which had settled in the Schoharie Valley

Schoharie Creek

Schoharie Creek in New York, USA flows north from the foot of Indian Head Mountain in the Catskill Mountains through the Schoharie Valley to the Mohawk River. It is twice impounded north of Prattsville to create New York City's Schoharie Reservoir and the Blenheim-Gilboa Power Project.Two notable...

in the early years of the 18th century. His mother, Margaret Levering (Miller) Sternberg, was the daughter of George B. Miller, also a Lutheran clergyman and professor of theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

at the seminary, which was a Lutheran school. He was the eldest child of a large family and he was given adult responsibilities from an early age. He interrupted his studies at the seminary with a year of work in a bookstore in Cooperstown

Cooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in Otsego County, New York, USA. It is located in the Town of Otsego. The population was estimated to be 1,852 at the 2010 census.The Village of Cooperstown is the county seat of Otsego County, New York...

and three years of teaching in nearby rural schools. During his last year at Hartwick he was an instructor in mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, chemistry

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

, and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

. He was at the same time pursuing the study of medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

with Horace Lathrop of Cooperstown. For his formal medical training he went first to Buffalo

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

, and later to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York (M.D.

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

degree, 1860). After graduation he settled in Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth is a city in Union County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city had a total population of 124,969, retaining its ranking as New Jersey's fourth largest city with an increase of 4,401 residents from its 2000 Census population of 120,568...

to practice, remaining there until the outbreak of the Civil War.

Junior Army surgeon

On May 28, 1861, he was appointed an Assistant SurgeonMedical Corps (United States Army)

The Medical Corps of the U.S. Army is a staff corps of the U.S. Army Medical Department consisting of commissioned medical officers – physicians with either an MD or a DO degree, at least one year of post-graduate clinical training, and a state medical license.The MC traces its earliest origins...

in the U.S. Army, and on July 21 of the same year was captured at the First Battle of Bull Run

First Battle of Bull Run

First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas , was fought on July 21, 1861, in Prince William County, Virginia, near the City of Manassas...

, while serving with General George Sykes

George Sykes

George Sykes was a career United States Army officer and a Union General during the American Civil War.-Early life:...

' division. He managed to escape and soon joined his command in the defense of Washington. He later participated in the Peninsular campaign and saw service in the battles of Gaines' Mill

Battle of Gaines' Mill

The Battle of Gaines's Mill, sometimes known as the First Battle of Cold Harbor or the Battle of Chickahominy River, took place on June 27, 1862, in Hanover County, Virginia, as the third of the Seven Days Battles of the American Civil War...

and Malvern Hill

Battle of Malvern Hill

The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, took place on July 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, on the seventh and last day of the Seven Days Battles of the American Civil War. Gen. Robert E. Lee launched a series of disjointed assaults on the nearly impregnable...

. During this campaign he contracted typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

while at Harrison's Landing and was sent north on a transport. During the remainder of the war he performed hospital duty, mostly at Portsmouth Grove, Rhode Island, and at Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Cuyahoga County, the most populous county in the state. The city is located in northeastern Ohio on the southern shore of Lake Erie, approximately west of the Pennsylvania border...

. On March 13, 1865, he was given the Brevet

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

s of captain and major

Major (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, major is a field grade military officer rank just above the rank of captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel...

for faithful and meritorious service.

The years following the war followed the pattern of frequent moves typical of junior medical officers of the day. He married Louisa Russell, daughter of Robert Russell of Cooperstown, on October 19, 1865 and took his bride to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, from where he was soon transferred to Fort Harker

Fort Harker (Kansas)

Fort Harker, located in Kanopolis, Kansas, was an active military installation of the United States Army from November 17, 1866 to October 5, 1872. The fortification was named after General Charles Garrison Harker, who was killed in action at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain in the American Civil War...

, near Ellsworth

Ellsworth, Kansas

Ellsworth is a city in and the county seat of Ellsworth County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 3,120.-19th century:...

in Kansas

Kansas

Kansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

. Louisa did not accompany him to the latter post, but joined him in 1867 just prior to an outbreak of cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

. She was one of the first civilians to develop the disease which killed her within a few hours on July 15 and soon claimed a toll of about 75 people at the fort.

Paleontology

Sternberg was promoted to captain on May 28, 1866 and was soon sent to Fort Riley, Kansas (December 1867). With troops from this post he took part (1868–69) in several expeditions against hostile CheyenneCheyenne

Cheyenne are a Native American people of the Great Plains, who are of the Algonquian language family. The Cheyenne Nation is composed of two united tribes, the Só'taeo'o and the Tsétsêhéstâhese .The Cheyenne are thought to have branched off other tribes of Algonquian stock inhabiting lands...

Indians along the upper Arkansas River

Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. The Arkansas generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's initial basin starts in the Western United States in Colorado, specifically the Arkansas...

in Indian Territory and in western Kansas. Besides his military duties, Sternberg was also interested in fossils and began collecting leaf imprints from the nearby Dakota Sandstone Formation

Dakota Sandstone

The Dakota Sandstone is a general term for an ill-defined early Cretaceous formation of the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains. It consists of sandy, shallow-marine deposits with intermittent mud flat sediments, and occasional stream deposits...

. Some of his specimens went back East where they were studied by the famous paleobotanist, Leo Lesquereux

Leo Lesquereux

Charles Léo Lesquereux was a Swiss bryologist and a pioneer of American paleobotany. He was born in the town of Fleurier, located in the canton of Neuchâtel....

.

Sternberg also collected vertebrate fossils, including shark teeth, fish remains and mosasaur bones, from the Smoky Hill Chalk

Smoky Hill Chalk

The Smoky Hill Chalk Member of the Niobrara Chalk formation is a Cretaceous conservation Lagerstätte, or fossil rich geological formation, known primarily for its exceptionally well-preserved marine reptiles. The Smoky Hill Chalk Member is the uppermost of the two structural units of the Niobrara...

and Pierre Shale formations in western Kansas, and sent the specimens back to Washington, D.C., where they were eventually curated in the United States National Museum (Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

). There they were studied and later described in publications by Joseph Leidy

Joseph Leidy

Joseph Leidy was an American paleontologist.Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, and later was a professor of natural history at Swarthmore College. His book Extinct Fauna of Dakota and Nebraska contained many species not previously described and many previously...

. The type specimen of the giant Late Cretaceous

Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous period is divided in the geologic timescale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous series...

fish, Xiphactinus audax, was collected by Dr. Sternberg. His work was also credited by Edward D. Cope and Samuel W. Williston. Sternberg was also responsible for getting his younger brother, Charles H. Sternberg, started in paleontology

Paleontology

Paleontology "old, ancient", ὄν, ὀντ- "being, creature", and λόγος "speech, thought") is the study of prehistoric life. It includes the study of fossils to determine organisms' evolution and interactions with each other and their environments...

. Charles would later credit his older brother for getting many other paleontologists of the day interested in the fossil resources of Kansas.

Sternberg served at Fort Riley until July 1870, when be was ordered to Governors Island, New York. In the meantime, he had remarried on September 1, 1869, at Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Indiana, and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city's population is 839,489. It is by far Indiana's largest city and, as of the 2010 U.S...

, to Martha L. Pattison, a daughter of Thomas T. N. Pattison of that city.

Yellow fever

During two years at Governors Island and three (1872–75) at Fort BarrancasFort Barrancas

Fort Barrancas or Fort San Carlos de Barrancas is a historic United States military fort in the Warrington area of Pensacola, Florida, located physically on Naval Air Station Pensacola....

, Florida, Sternberg had frequent contacts with yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

patients, and at the latter post, he contracted the disease himself. He had earlier noted the efficiency of moving inhabitants out of an infested environment and successfully applied that method to the Barrancas garrison. At about this time, Sternberg published two articles in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal ("An Inquiry into the Modus Operandi of the Yellow Fever Poison," July 1875, and "A Study of the Natural History of Yellow Fever," March 1877) which gained him status as an authority on yellow fever. While convalescing from his bout with the disease in 1877 be was ordered to Fort Walla Walla

Fort Walla Walla

Fort Walla Walla is a fort located in Walla Walla, Washington. It was established in 1858. Today, the complex contains a park, a museum, and a hospital.Fort Walla Walla should be distinguished from Fort Nez Percés or Old Fort Walla Walla ....

, Washington, and later that year he participated in a campaign against the Nez Perce Indians. The spent his spare hours in study and experimentation which laid a foundation for his later work. In 1870 he perfected an anemometer

Anemometer

An anemometer is a device for measuring wind speed, and is a common weather station instrument. The term is derived from the Greek word anemos, meaning wind, and is used to describe any airspeed measurement instrument used in meteorology or aerodynamics...

and patented an automatic heat regulator which later saw wide use.

On December 1, 1875, Sternberg was promoted major, and in April 1879, he was ordered to Washington, D. C., and detailed with the 1880 Havana Yellow Fever Commission. His medical colleagues on the Commission were Doctors Stanfard Chaille of New Orleans and Juan Guiteras

Juan Guiteras

Juan Guitéras y Gener , was a Cuban physician and pathologist specializing in yellow fever....

of Havana

Havana

Havana is the capital city, province, major port, and leading commercial centre of Cuba. The city proper has a population of 2.1 million inhabitants, and it spans a total of — making it the largest city in the Caribbean region, and the most populous...

. Sternberg was assigned to work on the problems relating to the nature and natural history of the disease and especially to its etiology

Etiology

Etiology is the study of causation, or origination. The word is derived from the Greek , aitiologia, "giving a reason for" ....

(origins). This involved the microscopical examination of blood and tissues in which he was one of the first to employ the newly discovered process of photomicrography. He developed high efficiency in its use. In the course of this work, he spent three months in Havana closely associated with Dr. Carlos Finlay

Carlos Finlay

Carlos Juan Finlay was a Cuban physician and scientist recognized as a pioneer in yellow fever research.- Early life and education :...

, the main proponent of the theory of mosquito transmission of yellow fever.

Bacteriology milestones

In 1880, the Commission concluded that the solution of yellow fever causality must await further progress in the new science of bacteriologyBacteriology

Bacteriology is the study of bacteria. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classification, and characterization of bacterial species...

. Sternberg was soon sent to New Orleans to investigate the conflicting discoveries of Plasmodium malariae

Plasmodium malariae

Plasmodium malariae is a parasitic protozoa that causes malaria in humans. It is closely related to Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax which are responsible for most malarial infection. While found worldwide, it is a so-called "benign malaria" and is not nearly as dangerous as that...

by Alphonse Laveran, and of Bacillus malariae by Edwin Klebs

Edwin Klebs

Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs was a German-Swiss pathologist. He is mainly known for his work on infectious diseases. He is the father of Arnold Klebs.-Life:...

and Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli. His report (1881) declared that the Bacillus malariae had no part in the causation of malaria. The same year — simultaneously with Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist born in Dole. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccine for rabies and anthrax. His experiments...

— he announced the discovery of the pneumococcus

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Streptococcus pneumoniae, or pneumococcus, is Gram-positive, alpha-hemolytic, aerotolerant anaerobic member of the genus Streptococcus. A significant human pathogenic bacterium, S...

, eventually recognized as the pathogenic agent of lobar pneumonia

Lobar pneumonia

Lobar pneumonia is a form of pneumonia that affects a large and continuous area of the lobe of a lung.It is one of the two anatomic classifications of pneumonia .- Symptoms :...

. He was the first in the United States to demonstrate the Plasmodium

Plasmodium

Plasmodium is a genus of parasitic protists. Infection by these organisms is known as malaria. The genus Plasmodium was described in 1885 by Ettore Marchiafava and Angelo Celli. Currently over 200 species of this genus are recognized and new species continue to be described.Of the over 200 known...

organism as cause of malaria (1885) and the to confirm the causitive roles of the bacilli of tuberculosis and typhoid fever (1886). He was the first scientist to produce photomicrographs of the tubercule bacillus

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a pathogenic bacterial species in the genus Mycobacterium and the causative agent of most cases of tuberculosis . First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, M...

. He was also the earliest American pioneer in the related field of disinfection in which he began with experiments (1878) with putrefactive bacteria

Putrefaction

Putrefaction is one of seven stages in the decomposition of the body of a dead animal. It can be viewed, in broad terms, as the decomposition of proteins, in a process that results in the eventual breakdown of cohesion between tissues and the liquefaction of most organs.-Description:In terms of...

. This work was continued in Washington and in the laboratories of Johns Hopkins Hospital

Johns Hopkins Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital is the teaching hospital and biomedical research facility of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, located in Baltimore, Maryland . It was founded using money from a bequest by philanthropist Johns Hopkins...

in Baltimore

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, under the auspices of the American Public Health Association

American Public Health Association

The American Public Health Association is Washington, D.C.-based professional organization for public health professionals in the United States. Founded in 1872 by Dr. Stephen Smith, APHA has more than 30,000 members worldwide...

. For his essay "Disinfection and Individual Prophylaxis against Infectious Diseases" (1886), later translated into several languages, he was awarded the Lomb Prize. He oversaw creation the US Army enlisted hospital corps ("medics") in 1887.

During the Hamburg

Hamburg

-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

cholera epidemic of 1892 he was detailed for duty with the New York quarantine station as a consultant on disinfection as applied to ships, their personnel, and cargo. Although some cases of the disease reached United States shores, none developed within the country.

Surgeon General

Sternberg was promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 2, 1891. In 1892 he published his Manual of Bacteriology, the first exhaustive treatise on the subject produced in the United States. With the retirement of Surgeon General Sutherland (May 1893), Sternberg, along with many others, submitted his claims for consideration for the vacancy. Although hardly the seniormost officer in the Medical Corps, he was among the top dozen and was without question the most eminent professional scientist in the service. He received the appointment of Surgeon General by President Grover ClevelandGrover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States. Cleveland is the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms and therefore is the only individual to be counted twice in the numbering of the presidents...

on May 30, 1893, with promotion to the grade of brigadier general.

Sternberg's nine year tenure (1893–1902) as Surgeon General coincided with immense professional progress in the field of bacteriology as well as the occurrence of the Spanish-American War

Spanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

. He was responsible for the 1893 establishment of the Army Medical School

Army Medical School

Founded by U.S. Army Brigadier General George Miller Sternberg, MD in 1893, the Army Medical School was by some reckonings the world's first school of public health and preventive medicine...

(precursor of today's Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

This article is about the U.S. Army medical research institute . Otherwise, see Walter Reed .The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research is the largest biomedical research facility administered by the U.S. Department of Defense...

), the organization of a contract dental service, the creation of the tuberculosis hospital at Fort Bayard, New Mexico, and of a special surgical hospital at Washington Barracks. The equipment of the medical school included laboratories of chemistry and bacteriology, and a liberal-minded policy was adopted in the supply of laboratory supplies to the larger military hospitals. With the Spanish-American War and its epidemic of typhoid fever, the problem of field hospitalization was confronted with fair success. (He was subjected to much criticism for conditions at these hospitals, but made little reply.) Sternberg created the Typhoid Fever Board (1898), consisting of Majors Walter Reed

Walter Reed

Major Walter Reed, M.D., was a U.S. Army physician who in 1900 led the team that postulated and confirmed the theory that yellow fever is transmitted by a particular mosquito species, rather than by direct contact...

, Victor C. Vaughan, and Edward O. Shakespeare, which established the facts of contact infection and fly carriage of the disease. In 1900 he organized the Yellow Fever Commission, headed by Reed, which ultimately fixed the transmission of yellow fever upon a particular species of mosquito. (These became celebrated as the “Walter Reed Boards”). On his recommendation the first tropical disease board was also established in Manila (January 1900) where it continued for about the next two years. In 1901, Sternberg oversaw the establishment of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

Sternberg was retired on account of age on June 8, 1902, and devoted the later years of his life to social welfare activities in Washington, particularly to the sanitary improvement of dwellings and to the care of tuberculous patients. Sternberg died at his home in Washington, on November 3, 1915.

Legacy

On Sternberg’s monument in Arlington National CemeteryArlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

is the inscription:

Pioneer American Bacteriologist, distinguished by his studies of the causation and prevention of infectious diseases, by his discovery of the microorganism causing pneumonia, and scientific investigations of yellow fever, which paved the way for the experimental demonstration of the mode of transmission of this pestilence. Veteran of three wars, breveted for bravery in action in the Civil War and the Nez Perce Wars. Served as Surgeon General of United States Army for period of nine years including the Spanish War. Founder of the Army Medical School. Scientist, author and philanthropist. M. D., LL. D.

Along with Pasteur and Koch, Sternberg is credited with first bringing the fundamental principles and techniques of the new science of bacteriology within the reach of the average physician.

Awards and accolades

- Honorary degree of LL.D., University of Michigan (1894)

- Honorary degree of LL.D., Brown University (1897).

- Honorary member, Epidemiological Society of London, the Royal Academy of Rome, the Academy of Medicine of Rio Janeiro, the American Academy of Medicine, and the French Society of Hygiene.

- Member (and one time president) of the American Medical AssociationAmerican Medical AssociationThe American Medical Association , founded in 1847 and incorporated in 1897, is the largest association of medical doctors and medical students in the United States.-Scope and operations:...

, the American Public Health AssociationAmerican Public Health AssociationThe American Public Health Association is Washington, D.C.-based professional organization for public health professionals in the United States. Founded in 1872 by Dr. Stephen Smith, APHA has more than 30,000 members worldwide...

, the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States, the Washington Biological Society, and the Philosophical Society of the District of ColumbiaPhilosophical Society of WashingtonThe Philosophical Society of Washington is the oldest scientific society in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1871 by Joseph Henry.Its aims are "the promotion of science, the advancement of learning, and the free exchange of views among its members on scientific subjects."Since 1887, the regular...

.

Miscellany

- Frank Heynick, author of a gigantic tome, Jews and Medicine: An Epic Saga (2003), was dismayed to come across the name of George Sternberg as he was finalizing his manuscript. He had not mentioned Sternberg in his book and the idea of researching yet another life, adding more pages to the 600 page book, and trimming back other parts was disheartening. Further research on Sternberg’s background ensued. As it turned out Sternberg was not, in fact, Jewish — “Thank heavens!” said the ecstatic Heynick.

See also

- United States Army Medical Department MuseumUnited States Army Medical Department MuseumThe U.S. Army Medical Department Museum or AMEDD Museum, Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas, originated as part of the Army's Field Service School at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. It moved to Fort Sam Houston in 1946. It is currently a component of the U.S...

, Ft Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas

External links

- Video: Sternberg Medical Pioneers Biography on Health.mil – The Military Health System provides a look at the life and work of George Sternberg.

- The Surgeons General of the U.S. Army and Their Predecessors at the Office of Medical History, OTSG Website

- Biography at Virtualology.com

- Dr. George M. Sternberg - Oceans of Kansas

- Xiphactinus audax - Oceans of Kansas