Frederick Augusta Barnard

Encyclopedia

Royal Guelphic Order

The Royal Guelphic Order, sometimes also referred to as the Hanoverian Guelphic Order, is a Hanoverian order of chivalry instituted on 28 April 1815 by the Prince Regent . It has not been conferred by the British Crown since the death of King William IV in 1837, when the personal union of the...

(1 September 1743 – 27 January 1830) was principal librarian to George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

during much of the English King's

British Royal Family

The British Royal Family is the group of close relatives of the monarch of the United Kingdom. The term is also commonly applied to the same group of people as the relations of the monarch in her or his role as sovereign of any of the other Commonwealth realms, thus sometimes at variance with...

reign. Barnard developed the library collection systematically, seeking guidance from noted intellectuals including writer and lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

.

Birth and parentage

Frederick Augusta Barnard was the son of John Barnard (†1773), a Gentleman UsherGentleman Usher

Gentleman Usher is a title for some officers of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom. See List of Gentlemen Ushers for a list of office-holders.-Historical:...

, Quarterly Waiter and Page of the Backstairs

Page of the Backstairs

A Page of the Backstairs is a senior servant of the British Royal Household who personally attends to the Sovereign and/or spouse ....

to Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales was a member of the House of Hanover and therefore of the Hanoverian and later British Royal Family, the eldest son of George II and father of George III, as well as the great-grandfather of Queen Victoria...

. His mother was Elizabeth Smith, who had married John Barnard at Berwick Street Chapel, St James, Westminster, in 1740/1. Barnard was born 1 September 1743 and was baptised at St James, Westminster, 30 September 1743, and was almost certainly a godson of the Prince and his wife Princess Augusta of Saxe-Coburg.

When Barnard died (1830), The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine

The Gentleman's Magazine was founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term "magazine" for a periodical...

stated 'He was presumed to be a natural son of Frederick, Prince of Wales', a statement repeated in the same magazine in 1834, repeated in Edward Edwards, Lives of the founders of the British Museum (1870), page 468, and several subsequent reference works, and perpetuated by a descendant, the herald James Arnold Frere

James Frere

James Arnold Frere, FSA was an officer of arms at the College of Arms in London.-Biography:He was the only son of John Geoffrey Frere of Hartley and Violet Ivy Sparks. Following military service in the Intelligence Corps, he began his heraldic career on 24 February 1948 when he was appointed...

, in his The British Monarchy at home (1963), pages 42, 45 and 139.

The claim, not based on any earlier record, seems to have originated in the belief that Barnard was Prince Frederick's son by his mistress Anne Vane, the daughter of Lord Barnard, as has been stated by one genealogist, but since Anne died in 1736, that is not possible. That he was the son of John Barnard is proved by the latter's will, dated 2 April 1772, which quotes the terms of his marriage settlement, dated 26 June 1741, which made provision of £5,000 for his wife if she survived him, and then for her children. The will states 'whereas my late wife has departed this life leaving three children by her body by me (viz) the said Elizabeth Barnard and Frederick Augusta Barnard and Mary Barnard now all living". The will further mentions related orders of the Court of Chancery on 24 February 1762 when Samuel Wright was ordered to pay £5,000 to the Accountant General (John's wife Elizabeth having presumably died), and on 28 June 1768 when application was successfully made for the funds, all the children having attained their majorities. The £5,000 was then bequeathed to the three children, the son receiving less than the daughters, he "being happily provided for in his Majesty's service".

Early career

Barnard's introduction to royal service was as Page of the Backstairs to George III, appointed to that post on 26 December 1760. By 1773 he was Librarian at Buckingham PalaceBuckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

, a post he held until 1830.

The Royal Library

On George III's accession in 1760, he found a Royal Library of little substance since the Old Royal Library had been moved from St James's Palace in 1708, and donated to the new British MuseumBritish Museum

The British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

by George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

in 1757. The library that George III inherited consisted of a few collections scattered among the various royal residences.

Early in his reign George determined to start a new library worthy of a monarch, and reflecting his patronage, taste and power. As a first step, he acquired in 1763 the library of Joseph Smith (1682-1770), former British Consul at Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

. Smith's collection contained many classics that were important examples of early printing. Starting around this period George delegated buyers to attend all major book sales in London and the Continent. Single volumes, private collections and large numbers of books from Jesuit libraries that had closed down, found their way to London and the new library.

George continued enlarging his library for some fifty years. He acquired the best books at the auctions of West, Ratcliffe and Askew, and continued buying up to the Roxburghe sale of 1812. Messrs Nicol, the booksellers, were his usual agents, though he retrieved from the Continent some priceless incunabula through Horn of Ratisbon, a notorious plunderer of the German convents.

This collection, which came to be known as the King's Library

King's Library

The King's Library was one of the most important collections of books and pamphlets of the Age of Enlightenment. Assembled by George III, this scholarly library of over 65,000 volumes was subsequently given to the British nation by George IV. It was housed in a specially built gallery in the...

, held numerous volumes on classical, English and Italian literature, European history and religion, and had examples of early printing, including a copy of the Gutenberg Bible

Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible was the first major book printed with a movable type printing press, and marked the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of the printed book. Widely praised for its high aesthetic and artistic qualities, the book has an iconic status...

, and William Caxton

William Caxton

William Caxton was an English merchant, diplomat, writer and printer. As far as is known, he was the first English person to work as a printer and the first to introduce a printing press into England...

's first edition of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. The collection included less-scholarly material, such as current magazines and newspapers. Numerous manuscripts and bound volumes of maps and topographical views rounded off the collection. The library had grown to some 65 000 volumes and 19 000 pamphlets by the time of George's death (1820).

A policy was eventually instituted of making the library's resources freely available to scholars, but initially George regarded the collection as his personal property and only grudgingly allowed access to Joseph Priestly and the American revolutionary John Adams

John Adams

John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States...

, though Samuel Johnson was always welcomed.

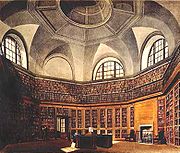

The collection was first housed in the Old Palace

Croydon Palace

Croydon Palace, in Croydon, now part of south London, was the summer residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury for over 500 years. Regular visitors included Henry III and Queen Elizabeth I...

at Kew

Kew

Kew is a place in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames in South West London. Kew is best known for being the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens, now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace...

, then was moved to the Octagon Library which had been specially constructed at the Queen's House or Buckingham House, on the site of the present Buckingham Palace. Here it remained until George IV

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

, after his father's death in 1820, decided to rebuild Buckingham House into a suitable palace for himself. George IV had little interest in the library, and he donated it to the British public in 1823.

Catalogue

For a long time George III had wanted a catalogue of the collection published, but kept postponing this. It became evident after 1812 that he would not recover from his condition, and Queen Charlotte and the Prince Regent urged that the catalogue be finalised. Barnard compiled and published it as Bibliothecae Regiae Catalogus printed by W. Bulmer & W. Nicol of London between 1820 and 1829 in five folio volumes. Although it was never offered for sale to the public, copies were presented to the crowned heads of Europe and important libraries in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.Later life

Barnard had been elected a Fellow of the Society of AntiquariesSociety of Antiquaries of London

The Society of Antiquaries of London is a learned society "charged by its Royal Charter of 1751 with 'the encouragement, advancement and furtherance of the study and knowledge of the antiquities and history of this and other countries'." It is based at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London , and is...

in 1789 and a Fellow of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

in 1790. He was distressed to witness the dispersal of the collection he had helped to assemble, but he was made Knight Commander of the Order of the Guelphs (Knight of Hanover, or K.C.H.) in 1828.

Family

On 28 October 1776 Barnard married Catherine Byde, the daughter of John Byde at St. George Hanover Square, London. They had a son, George, and possibly a daughter. Catherine died in 1837.Barnard lived for most of his working life in a Grace and favour

Grace and favour

A grace and favour home is a residential property owned by a monarch by virtue of their position as head of state and leased rent-free to persons as part of an employment package or in gratitude for past services rendered....

apartment in St James's Palace and died there 27 January 1830, aged 87.

Barnard's will of 2 July 1827 mentions a house at Twickenham and named his wife as principal beneficiary, and also made provision for his grandson. Barnard was buried in a vault under St Martin-in-the-Fields, London, 3 February 1830, but he and his wife were removed to Kensal Green Cemetery, 1 February 1859.

Barnard's son, George (1777–1817) had a son, also named George, who died in 1846.