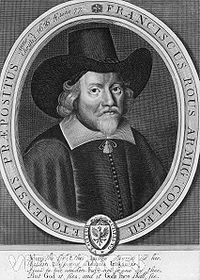

Francis Rous

Encyclopedia

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

. He was also Provost of Eton, and wrote several theological and devotional works.

Early life

He was born at DittishamDittisham

Dittisham is a village and civil parish in the South Hams district of the English county of Devon. It is situated on the banks of the tidal River Dart, some upstream of Dartmouth....

in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

in 1579, and educated at Broadgates Hall, Oxford and the University of Leiden, graduating at the former in January 1596-97, and at the latter thirteen months afterwards. In 1601 he entered the Middle Temple

Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers; the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn...

, but soon afterwards retired to Landrake

Landrake

Landrake is a village in southeast Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is situated approximately three miles west of Saltash in the civil parish of Landrake with St Erney...

. For some years he lived in seclusion in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

and occupied himself with theological studies.

Parliamentary career

He took a leading part in Parliament: he was elected to Parliament for CornwallCornwall (UK Parliament constituency)

Cornwall is a former county constituency covering the county of Cornwall, in the South West of England. It was a constituency of the House of Commons of England then of the House of Commons of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1832...

in 1604 and 1656; for Truro 1626, 1640 (twice) and 1654; for Tregony

Tregony (UK Parliament constituency)

Tregony was a rotten borough in Cornwall which was represented in the Model Parliament of 1295, and returned two Members of Parliament to the English and later British Parliament continuously from 1562 to 1832, when it was abolished by the Great Reform Act....

1628; and for Devon

Devon (UK Parliament constituency)

Devon was a parliamentary constituency covering the county of Devon in England. It was represented by two Knights of the Shire, in the House of Commons of England until 1707, then of the House of Commons of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and finally the House of Commons of the United Kingdom from...

1653. In the 1628 parliament he took part in the ferocious criticisms of Roger Mainwaring.

In the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

Rous opened the debate on the legality of William Laud

William Laud

William Laud was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 to 1645. One of the High Church Caroline divines, he opposed radical forms of Puritanism...

's new canons on 9 December 1640, and presented the articles of impeachment

Impeachment

Impeachment is a formal process in which an official is accused of unlawful activity, the outcome of which, depending on the country, may include the removal of that official from office as well as other punishment....

against John Cosin

John Cosin

John Cosin was an English churchman.-Life:He was born at Norwich, and was educated at Norwich grammar school and at Caius College, Cambridge, where he was scholar and afterwards fellow. On taking orders he was appointed secretary to Bishop Overall of Lichfield, and then domestic chaplain to...

on 15 March 1641. When the Westminster Assembly

Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was appointed by the Long Parliament to restructure the Church of England. It also included representatives of religious leaders from Scotland...

was set up, 12 June 1643, he was nominated one of its lay assessors, and on 23 September 1643 he took the Solemn League and Covenant

Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians. It was agreed to in 1643, during the First English Civil War....

. He was chairman of the committee for ordination of ministers constituted on 2 October 1643 following, and a member of the committee of appeals appointed for the visitation of the University of Oxford on 1 May 1647. On 16 July 1648 he was sworn of the Derby House Committee.

He was Speaker of the House

Speaker of the British House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons is the presiding officer of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is John Bercow, who was elected on 22 June 2009, following the resignation of Michael Martin...

during Barebone's Parliament of The Protectorate

The Protectorate

In British history, the Protectorate was the period 1653–1659 during which the Commonwealth of England was governed by a Lord Protector.-Background:...

. In 1657 he offered a seat in Cromwell's House of Lords, but did not take it.

Other service and later life

He obtained many offices under the Commonwealth, among them that of provost of Eton College. At first a Presbyterian, he afterwards joined the Independents, in 1649. In early 1652 he served on the committee for propagation of the gospel, which framed an abortive scheme for a state churchState church

State churches are organizational bodies within a Christian denomination which are given official status or operated by a state.State churches are not necessarily national churches in the ethnic sense of the term, but the two concepts may overlap in the case of a nation state where the state...

on a congregational plan. When Barebone's Parliament dissolved itself, Rous was sworn in on Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

's council of state. In 1654 he was on the committee for approbation of public preachers; he was also one of the committee appointed on 9 April 1656 to discuss the question of the kingship with Cromwell. He died in Acton.

Works

While at Oxford he contributed a sonnet to Charles Fitz-Geffrey's Sir Francis Drake his Honourable Life's Commendation(1596). In imitation of Edmund SpenserEdmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and one of the greatest poets in the English...

, he wrote a poem in two books, entitled Thule, or Virtue's History (1598).

The theological works that first made his name were:

- Meditations of Instruction, of Exhortation, of Reprofe: indeavouring the Edification and Reparation of the House of God (1616);

- The Arte of Happines, consisting of three Parts, whereof the first searcheth out the Happinesse of Man, the second particularly discovers and approves it, the third sheweth the Meanes to attayne and increase it, (1619 and 1631);

- Diseases of the Time attended by their Remedies (1622);

- Oyl of Scorpions (1623).

Testis Veritatis (1626) was a reply to Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu

Richard Montagu was an English cleric and prelate.-Early life:He was born during Christmastide 1577 at Dorney, Buckinghamshire, where his father Laurence Mountague was vicar, and was educated at Eton. He was elected from Eton to a scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, and admitted on 24...

's Appello Caesarem. Catholicke Charity: complaining and maintaining that Rome is uncharitable to sundry eminent Parts of the Catholicke Church (1641) was written earlier, as a reply to a 1630 work of the Catholic Tobie Matthew

Tobie Matthew

Sir Tobie Matthew , born in Salisbury, was an English member of parliament and courtier who converted to Roman Catholicism and became a priest...

, but could not be printed in the Laudian 1630s.

He was a versifier of the Psalms

Psalms

The Book of Psalms , commonly referred to simply as Psalms, is a book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Bible...

. His translation, with some modifications, was adopted by the Church and Parliament of Scotland

Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament is the devolved national, unicameral legislature of Scotland, located in the Holyrood area of the capital, Edinburgh. The Parliament, informally referred to as "Holyrood", is a democratically elected body comprising 129 members known as Members of the Scottish Parliament...

for use in public worship, a position which it held almost exclusively until the middle of the 19th century.

The subjective cast of his piety is reflected in his Mystical Marriage . . . betweene a Soule and her Saviour (1635). There is some doubt about the attribution to Rous of co-authorship in The Ancient Bounds, a work of 1645 advocating religious tolerance; some say he was an author, and that this has implications for his place on the spectrum of independents. A scholarly case has been made for the authorship of Joshua Sprigg

Joshua Sprigg

Joshua Sprigg or Sprigge was an English Independent theologian and preacher. He acted as chaplain to Sir Thomas Fairfax, general for the Parliamentarians, and wrote or co-wrote the 1647 book Anglia Rediviva, a history of the part played up to that time by Fairfax's army in the Wars of the Three...

.

Political thought

A debate was initiated by Rous in a brief pamphlet in April 1649 in which he argued that allegiance could be given to the Commonwealth even though it were achnowledged to be an illegal power. Rous focused on a key biblical text - holding that St Paul's injunction in Romans 13: 1-2 to obey "the powers that be" because they are ordained of God had to be taken literally. His essential argument, which in effect mirrored the doctrine of the Divine Right of KingsDivine Right of Kings

The divine right of kings or divine-right theory of kingship is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God...

, was that the mere fact that a government had the capacity to rule and was capable of commanding the subject's obedience was sufficient evidence of God's will and providence in establishing the government.

Rous's pamphlet was immediately attacked by those who argued that he was ignoring the Pauline distinction between authority and power: the anonymous author of The Grand Case of Conscience Stated (no place nor date of publication), for example, argued that "when any shall usurp Authority, by whatsoever title or force he procures it, such may be obeyed in reference to their power, while they command lawful things, but not in reference to Authority" (p. 3), yet "they cannot illegally get themselves the legal power, nor can they exclude others from their Authority, although by force they may keep them the exercise of it" (p. 8).

In his pamphlet, Rous deployed a secondary argument that did not rest on scripture but on a Hobbesian social contract. What Rous argued was that "when a person or persons have gotten Supreme Power, and by the same excluded all other from authority, either that authority which is thus taken by power must be obeyed, or else all authority and government must fall to the ground; and so confusion (which is worse than titular tyranny) be admitted into a Commonwealth" (Rous, Lawfulnes, pp. 7–8).

Family

His father was Sir Anthony Rous of HaltonHalton

- Places in the United Kingdom :* Halton , Cheshire**Halton **Halton, Cheshire village* Halton, Buckinghamshire village** RAF Halton* Halton, district of Leeds, West Yorkshire* Halton, Northumberland village...

; and John Pym

John Pym

John Pym was an English parliamentarian, leader of the Long Parliament and a prominent critic of James I and then Charles I.- Early life and education :...

was a stepbrother, his mother being Sir Anthony's second wife, Philipa Colles, daughter of Michael Colles and Mary Graunt.

By his wife Philipa (born 1575, died 20 December 1657, and buried in Acton church), Rous had a son Francis Rous (the younger), known as a writer. He was born at Saltash

Saltash

Saltash is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It has a population of 14,964. It lies in the south east of Cornwall, facing Plymouth over the River Tamar. It was in the Caradon district until March 2009 and is known as "the gateway to Cornwall". Saltash means ash tree by...

in 1615, and educated at Eton and Oxford, where he matriculated on 17 October 1634, and was elected to a postmastership at Merton College the same year. He afterwards migrated to Gloucester Hall. About 1640 he settled in London, where he practised medicine until his death in or about 1643. He contributed to Flos Britannicus veris novissimi filiola Carolo et Maryse nata xvii. Martii (1636) and compiled Archaeologiae Atticae Libri Tres (1637).

Further reading

- Colin Burrow, “Rous, Francis (1580/81–1659),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 (accessed 2 July 2008).