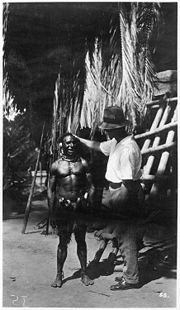

Ernest Chinnery

Encyclopedia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n anthropologist and public servant. He worked extensively in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

and visited communities along the Sepik

Sepik

Sepik may refer to places in Papua New Guinea:*Sepik River*East Sepik - a province*Sandaun - a province formerly known as West Sepik*Sepik region - consisting of East Sepik and Sandaun provincesIn languages it may refer to:...

river.

Early life

He was born on 5 November 1887 at Waterloo, VictoriaWaterloo, Victoria

Waterloo is a locality consisting of a collection of farms and houses approximately north of the town of Beaufort, Victoria and west north west of the state capital of Melbourne....

, son of John William Chinnery, a miner

Miner

A miner is a person whose work or business is to extract ore or minerals from the earth. Mining is one of the most dangerous trades in the world. In some countries miners lack social guarantees and in case of injury may be left to cope without assistance....

, and his wife Grace Newton, née Pearson, both of whom were Victorian-born. His father joined the Victorian Railways

Victorian Railways

The Victorian Railways operated railways in the Australian state of Victoria from 1859 to 1983. The first railways in Victoria were private companies, but when these companies failed or defaulted, the Victorian Railways was established to take over their operations...

and the young Chinnery was educated in the state schools of towns in which his father served.

Public service

Articled briefly to a MelbourneMelbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

law firm, Chinnery joined the public service of Papua

Papua (Australian territory)

The Territory of Papua comprised the southeastern quarter of the island of New Guinea from 1883 to 1949. It became a British Protectorate in the year 1884, and four years later it was formally annexed as British New Guinea...

in April 1909 as a clerk in Port Moresby

Port Moresby

Port Moresby , or Pot Mosbi in Tok Pisin, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea . It is located on the shores of the Gulf of Papua, on the southeastern coast of the island of New Guinea, which made it a prime objective for conquest by the Imperial Japanese forces during 1942–43...

. Seeking the prestige of field service, he won appointment as a patrol officer in July 1910 and was posted to Ioma

IOMA

IOMA is an evidence based skincare brand from France. It was founded in 2008 and it is now present in around 300 stores in France and in several other countries like the US.-Press:** **: Machines and Microchips...

in the Mambare division. In the Kumusi division for the next three years his work on routine patrols gained the confidence of local tribes in Papua New Guinea and he reputedly underwent a tribal initiation ceremony. Chinnery however was not on good terms either with local Europeans or with Lieutenant-Governor (Sir) Hubert Murray whom he personally disliked.

In November 1913 Chinnery was charged with infringing the field-staff regulations and was reduced in rank. In the Rigo

Rigo

Rigo may refer to:* Rigo 23, a Portuguese artist active in San Francisco, California* Blessed Rigo, also known as Henry of Treviso, a medieval Italian saint* Rigo Tovar, a Mexican cumbia singer...

district in 1914, while on patrol in an unavoidable incident he clashed with tribesmen and shot seven. By 1917 Chinnery was patrolling into new country in the central division behind Kairuku and into the Kunimaipa valley. He is credited with discovering the source of the Waria River

Waria River

The Waria River is a river in Oro Province and Morobe Province in south-eastern Papua New Guinea. It flows into the Solomon Sea. The river is fast-flowing with heavy sediment. The lower Waria Valley is home to the indigenous Zia tribe, flowing through the communities of Pema, Popoe and Saigara...

.

In 1915 he sought leave to enlist; it was granted in 1917 and in September he joined the Australian Flying Corps. Chinnery was demobilized in England late in 1919 as a lieutenant.

Anthropology

Chinnery had already previously published anthropological papers and now became a research student under A. C. Haddon at Christ's CollegeChrist's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.With a reputation for high academic standards, Christ's College averaged top place in the Tompkins Table from 1980-2000 . In 2011, Christ's was placed sixth.-College history:...

, Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

. He joined the research committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, lectured to the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

and in 1920 won its Cuthbert Peek award. Refused appointment as Papuan government anthropologist in 1921 because Murray distrusted him, he served New Guinea Copper Mines Ltd as labor adviser until in 1924 he was appointed government anthropologist of the Mandated Territory. He then published in British anthropological journals six official reports.

Chinnery became the territory's first director of district services and native affairs in 1932 and directed the early extension of control in the newly discovered central highland valleys. He encouraged anthropological reporting by his staff and strongly supported the training of field-officer cadets in anthropology at the University of Sydney

University of Sydney

The University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

. In 1930 and 1934 he represented Australia before the Permanent Mandates Commission

Permanent Mandates Commission

The Permanent Mandates Commission was the commission of the League of Nations responsible for oversight of mandates. The commission was established in 1919 under Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant and was headquartered at Geneva....

in Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

.

Following a major review of Aboriginal

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

policy in 1937-38, Chinnery was seconded from New Guinea in 1939 to head a specific new department of native affairs designed to introduce New Guinea methods to the Northern Territory. Living alone in his office, he learned a great deal but was affected by the dilemma created by military occupation. When his secondment expired in 1946 he planned to return to anthropology in New Guinea but found no support. He was then an Australian adviser at the Trusteeship Council, for the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

before retiring to Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

, in 1947. Chinnery had served twice on United Nations missions to Africa but never published the book he had planned.