Ancient Greek warfare

Encyclopedia

With the emergence of Ancient Greece

from its 'Dark Age

', the population seemed to have significantly risen, allowing restoration of urbanized culture, and the rise of the city-states (Poleis). Such developments would have consequently restored the possibility of organized warfare between statelets (as opposed to e.g. cattle-raiding etc.). Although it does not necessarily follow that conflict must occur, the fractious nature of Ancient Greek society seems to have made this inevitable. Concomitant with the rise of the city-state was the evolution of a new way of warfare - the hoplite

phalanx

.

When exactly this occurred is uncertain amongst historians, but it is thought to have been created by the Spartans in around 650 BC. The hoplite was a heavily armoured, spear-armed citizen-soldier, primarily drawn from the middle classes. Fighting in the tight phalanx formation maximised the effectiveness of the armour, large shields and spears carried by the hoplites, aiming to present an impenetrable wall of men. Warfare in the archaic period seems to have mostly occurred of small-scale, set-piece battles between very similar phalanxs from the city-states in conflict. Since the soldiers were primarily citizens with other occupations, warfare was limited to seasonal, relatively local and of low-intensity. Neither side could afford heavy casualties or sustained campaigns, so conflicts seem to have been resolved by single battles.

The scale and scope of warfare in Ancient Greece changed dramatically as a result of the Greco-Persian Wars

. To fight the enormous armies of the Achaemenid Empire

was effectively beyond the capabilities of a single city-state. The eventual triumph of the Greeks was achieved by alliances of many city-states (the exact composition changing over time), allowing the pooling of resources and division of labour. Although alliances between city states occurred before this time, nothing on this scale had been seen before. The rise of Athens

and Sparta

as pre-eminent powers during this conflict led directly to the Peloponnesian War

, which saw further development of the nature of warfare, strategy and tactics. Fought between leagues of cities dominated by Athens and Sparta, the increased manpower and financial resources increased the scale, and allowed the diversification of warfare. Set-piece battles during the Peloponnesian war proved indecisive and instead there was increased reliance on attritionary strategies, naval battle and blockades and sieges. These changes greatly increased the number of casualties and the disruption of Greek society.

Following the eventual defeat of the Athens in 404 BC, and the disbandment of the Athenian-dominated Delian League

, Ancient Greece fell under the hegemony

of Sparta. However, it was soon apparent that the hegemony was unstable, and the Persian Empire sponsored a rebellion by the combined powers of Athens, Thebes, Corinth

and Argos

, resulting in the Corinthian War

(395-387 BC). After largely inconclusive campaigning, the war was decided when the Persians switched to supporting the Spartans, in return for the cities of Ionia

and Spartan non-interference in Asia Minor

. This brought the rebels to terms, and restored the Spartan hegemony on a more stable footing. The Spartan hegemony would last another 16 years, until, at the Battle of Leuctra

(371) the Spartans were decisively defeated by the Theban general Epaminondas

.

In the aftermath of this, the Thebans acted with alacrity to establish a hegemony

of their own over Greece. However, Thebes lacked sufficient manpower and resources, and became overstreched in attempting to impose itself on the rest of Greece. Following the death of Epaminondas and loss of manpower at the Battle of Mantinea

(362 BCE), the Theban hegemony ceased. Indeed, the losses in the ten years of the Theban hegemony left all the Greek city-states weakened and divided. As such, the city-states of southern Greece would shortly afterwards be powerless to resist the rise of the Macedonian kingdom in the north. With revolutionary tactics, King Phillip II brought most of Greece under his sway, paving the way for the conquest of "the known world" by his son Alexander the Great. The rise of the Macedonian Kingdom is generally taken to signal the end of the Greek Classical period, and certainly marked the end of distinctive way of war in Ancient Greece.

The hoplite was a heavy infantryman, the central element of warfare in Ancient Greece. The word hoplite (Greek ὁπλίτης, hoplitēs) derives from hoplon (ὅπλον, plural hopla, ὅπλα) meaning an item of armor or equipment, thus 'hoplite' may approximate to 'armored man'. Hoplites were the citizen-soldiers of the Ancient Greek City-states. They were primarily armed as spear-men and fought in a phalanx.

The hoplite was a heavy infantryman, the central element of warfare in Ancient Greece. The word hoplite (Greek ὁπλίτης, hoplitēs) derives from hoplon (ὅπλον, plural hopla, ὅπλα) meaning an item of armor or equipment, thus 'hoplite' may approximate to 'armored man'. Hoplites were the citizen-soldiers of the Ancient Greek City-states. They were primarily armed as spear-men and fought in a phalanx.

The origins of the hoplite are obscure, and no small matter of contention amongst historians. Traditionally, this has been dated to the 8th century BCE, and attributed to Sparta; but more recent views suggest a later date, towards the 7th century BCE. Certainly, by approximately 650 BCE, as dated by the 'Chigi vase

', the 'hoplite revolution' was complete. The major innovation in the development of the hoplite seems to have been the characteristic circular shield (Aspis

), roughly 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter, and made of wood faced with bronze. Although very heavy (8 –), the design of this shield was such that it could be supported on the shoulder. More importantly, it permitted the formation of a shield-wall by an army, an impenetrable mass of men and shields. Men were also equipped with metal greaves and also a breast plate made of bronze, leather, or stiff cloth. When this was combined with the primary weapon of the hoplite, 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) long spear (the doru

), it gave both offensive and defensive capabilities.

Regardless of where it developed, the model for the hoplite army evidently quickly spread throughout Greece. The persuasive qualities of the phalanx were probably its relative simplicity (allowing its use by a citizen militia), low fatality rate (important for small city-states), and relatively low cost (enough for each hoplite to provide their own equipment). The Phalanx also became a source of political influence because men had to provide their own equipment in order to be a part of the army.

The hoplite phalanx of the Archaic

The hoplite phalanx of the Archaic

and Classical

periods in Greece (approx. 750-350 BCE) was a formation in which the hoplites would line up in ranks in close order. The hoplites would lock their shields together, and the first few ranks of soldiers would project their spears out over the first rank of shields. The phalanx therefore presented a shield wall and a mass of spear points to the enemy, making frontal assaults much more difficult. It also allowed a higher proportion of the soldiers to be actively engaged in combat at a given time (rather than just those in the front rank).

When advancing towards an enemy, the phalanx would break into a run that was sufficient enough to create momentum but not too much as to lose cohesion. The opposing sides would collide viciously, possibly terrifying many of the hoplites of the front row. The battle would then rely on the valour of the men in the front line; whilst those in the rear maintained forward pressure on the front ranks with their shields. When in combat, the whole formation would consistently press forward trying to break the enemy formation; thus when two phalanx formations engaged, the struggle essentially became a pushing match, in which, as a rule, the deeper phalanx would almost always win, with few recorded exceptions.

If battle was refused by one side, they would retreat to the city, in which case the attackers generally had to content themselves with ravaging the countryside around, since siegecraft was undeveloped. When battles occurred, they were usually set piece and intended to be decisive. The battlefield would be flat and open, reducing the possibilities for complex tactical maneuvers. These battles were short, bloody, and brutal, and thus required a high degree of discipline. At least in the early classical period, other troops were less important; (cavalry) generally protected the flanks, when present at all; and both light infantry and missile troops were negligible.

The strength of hoplites was shock combat. The two phalanxes would smash into each other in hopes of breaking or encircling the enemy force's line. Failing that, a battle degenerated into a pushing match, with the men in the rear trying to force the front lines through those of the enemy. This maneuver was known as the Othismos. Battles rarely lasted more than an hour. Once one of the lines broke, the troops would generally flee from the field, sometimes chased by peltasts or light cavalry. If a hoplite escaped, he would sometimes be forced to drop his cumbersome aspis, thereby disgracing himself to his friends and family. Casualties were slight compared to later battles, rarely amounting to more than 5% of the losing side, but the slain often included the most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front. Thus, the whole war could be decided by a single field battle; victory was enforced by ransoming the fallen back to the defeated, called the 'Custom of the Dead Greeks'.

Darius the Great

, and then his successor Xerxes I

to subjugate Ancient Greece. Darius was already ruler of the Greek cities of Ionia

, and the wars are taken to start when they rebelled in 499 BC. The revolt was crushed by 494 BC, but Darius resolved to bring mainland Greece under his dominion. Many city-states made their submission to him, but others did not, notably including Athens

and Sparta

. Darius thus sent his commanders Datis and Artaphernes to attack Attica

, to punish Athens for her intransigence. After burning Eretria

, the Persians landed at Marathon

.

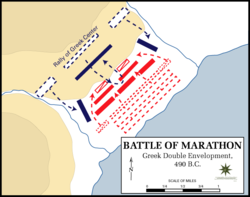

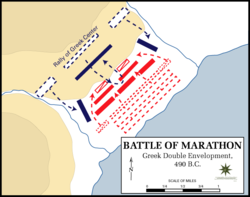

An Athenian army of c. 10,000 hoplites marched to meet Persian army of c. 20-60,000. The Athenians were at a significant disadvantage both strategically and tactically. Raising such a large army had denuded Athens of defenders, and thus any attack in the Athenian rear would cut off the Army from the City. Tactically, the hoplites were very vulnerable to attacks by cavalry , and the Athenians had no cavalry to defend the flanks. After several days of stalemate at Marathon, the Persian commanders attempted to take strategic advantage by sending their cavalry (by ship) to raid Athens itself. This gave the Athenian army a small window of opportunity to attack the remainder of the Persian Army.

This was the first true engagement

This was the first true engagement

between a hoplite army and a non-Greek army. The Persians had acquired a reputation for invincibility, but the Athenian hoplites proved crushingly superior in the ensuing infantry battle. To counter the massive numbers of Persians, the Greek general Miltiades

ordered the troops to be spread across an unusually wide front, leaving the centre of the Greek line undermanned. However, the lightly armoured Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured hoplites, and the Persian wings were quickly routed. The Greek wings then turned against the elite troops in the Persian centre, which had held the Greek centre until then. Marathon demonstrated to the Greeks the lethal potential of the hoplite, and firmly demonstrated that the Persians were not, after all, invincible.

The revenge of the Persians was postponed 10 years by internal conflicts in the Persian Empire, until Darius's son Xerxes returned to Greece in 480 BC with a staggeringly large army (modern estimates suggest between 150,000-250,000 men). Many Greeks city-states, having had plenty of warning of the forthcoming invasion, formed an anti-Persian league; though as before, other city-states remained neutral or allied with Persia. Although alliances between city-states were commonplace, the scale of this league was a novelty, and the first time that the Greeks had united in such a way to face an external threat.

This allowed diversification of the allied armed forces, rather than simply mustering a very large hoplite army. The visionary Athenian politician Themistocles

had successfully persuaded his fellow citizens to build a huge fleet in 483/82 BC to combat the Persian threat (and thus to effectively abandon their hoplite army, since there were not men enough for both). Amongst the allies therefore, Athens was able to form the core of a navy, whilst other cities, including of course Sparta, provided the army. This alliance thus removed the constraints on the type of armed forces that the Greeks could use. The use of such a large navy was also a novelty to the Greeks.

The second Persian invasion is famous for the battles of Thermopylae

and Salamis

. As the massive Persian army moved south through Greece, the allies sent a small holding force (c. 10,000) men under the Spartan king Leonidas, to block the pass of Thermopylae

whilst the main allied army could be assembled. The allied navy extended this blockade at sea, blocking the nearby straits of Artemisium

, to prevent the huge Persian navy landing troops in Leonidas's rear. Famously, Leonidas's men held the much larger Persian army at the pass (where their numbers counted for nothing) for three days, the hoplites again proving their superiority.

Only when a Persian force managed to outflank them by means of a mountain track was the allied army overcome; but by then Leonidas dismissed the majority of the troops, remaining with 300 Spartans (and perhaps 2000 other troops) to guard the pass, in the process making one of history's great last stands. The Greek navy, despite their lack of experience, also proved their worth holding back the Persian fleet whilst the army still held the pass.

Thermopylae provided the Greeks with time to arrange their defences, and they dug in across the Isthmus of Corinth

, an impregnable position; although an evacuated Athens was thereby sacrificed to the advancing Persians. In order to outflank the isthmus, Xerxes needed to use this fleet, and in turn therefore needed to defeat the Greek fleet; similarly, the Greeks needed to neutralise the Persian fleet to ensure their safety. To this end, the Greeks were able to lure the Persian fleet into the straits of Salamis

; and, in a battleground where Persian numbers again counted for nothing, they won a decisive victory

, justifying Themistocle's decision to build the Athenian fleet. Demoralised, Xerxes returned to Asia Minor with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius

to campaign in Greece the following year (479 BC).

However, a united Greek army of c. 40,000 hoplites decisively defeated Mardonius at the Battle of Plataea

, effectively ending the invasion. Almost simultaneously, the allied fleet defeated the remnants of the Persian navy at Mycale

, thus destroying the Persian hold on the islands of the Aegean

.

The remainder of the wars saw the Greeks take the fight to the Persians. The Athenian dominated Delian League

of cities and islands extirpated Persian garrisons from Macedon

and Thrace

, before eventually freeing the Ionian cities from Persian rule. At one point, the Greeks even attempted an invasion of Cyprus and Egypt (which proved disastrous)), demonstrating a major legacy of the Persian Wars: warfare in Greece had moved beyond the seasonal squabbles between city-states, to coordinated international actions involving huge armies. The ambitions of many Greek states had dramatically increased, and the tensions resulting from this would lead directly onto the Peloponnesian War

.

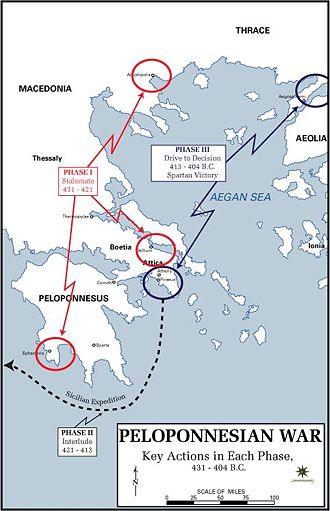

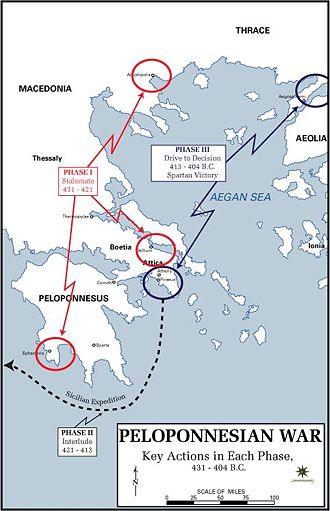

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), was fought between the Athenian dominated Delian League

The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), was fought between the Athenian dominated Delian League

and the Spartan dominated Peloponnesian League

. Whatever the proximal causes of the war, it was in essence a conflict between Athens and Sparta for supremacy in Greece. The war (or wars, since it is often divided into three periods) was for much of the time a stalemate, punctuated with occasional bouts of activity. Tactically the Peloponnesian war represents something of a stagnation; the strategic elements were most important as the two sides tried to break the deadlock, something of a novelty in Greek warfare.

Building on the experience of the Persian Wars, the diversification from core hoplite warfare, permitted by increased resources, continued. There was increased emphasis on navies, sieges, mercenaries and economic warfare. Far from the previously limited and formalized form of conflict, the Peloponnesian War transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with atrocities on a large scale; shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside and destroying whole cities.

From the start, the mismatch in the opposing forces was clear. The Delian League (hereafter 'Athenians') were primarily a naval powers, whereas the Peloponnesian League (hereafter 'Spartans') consisted of primarily land-based powers. The Athenians thus avoided battle on land, since they could not possibly win, and instead dominated the sea, blockading the Peloponnesus whilst maintaining their own trade. Conversely, the Spartans repeatedly invaded Attica

, but only for a few weeks at a time; they remained wedded to the idea of hoplite-as-citizen. Although both sides suffered setbacks and victories, the first phase essentially ended in stalemate, as neither league had the power to neutralise the other. The second phase, an Athenian expedition to attack Syracuse

in Sicily

achieved no tangible result other than a large loss of Athenian ships and men.

In the third phase of the war however the use of more sophisticated stratagems eventually allowed the Spartans to force Athens to surrender. Firstly, the Spartans permanently garrisoned a part of Attica, removing from Athenian control the silver mine which funded the war effort. Forced to squeeze even more money from her allies, the Athenian league thus became heavily strained. After the loss of Athenian ships and men in the Sicilian expedition, Sparta was able to foment rebellion amongst the Athenian league, which therefore massively reduced the ability of the Athenians to continue the war.

Athens in fact partially recovered from this setback between 410-406 BC, but a further act of economic war finally forced her defeat. Having developed a navy that was capable of taking on the much-weakened Athenian navy, the Spartan general Lysander

seized the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain. The remaining Athenian fleet was thereby forced to confront the Spartans, and were decisively defeated. Athens had little choice but to surrender; and was stripped of her city walls, overseas possessions and navy. In the aftermath, the Spartans were able to establish themselves as the dominant force in Greece for three decades.

s (javelin throwers) and archers. Many of these would have been mercenary troops, hired from outlying regions of Greece. For instance, the Agrianes

from Thrace

were well-renowned peltasts, whilst Crete

was famous for its archers. Since there were no decisive land-battles in the Peloponnesian War, the presence or absence of these troops was unlikely to have affected the course of the war. Nevertheless, it was in important innovation, one which was developed much further in later conflicts.

. The Spartans did not feel strong enough to impose their will on a shattered Athens. Undoubtedly part of the reason for the weakness of the hegemony was a decline in the Spartan population.

The first major challenge to the Spartan hegemony occurred in the Corinthian War

(395-387 BC). Sensing the Spartan weakness, an alliance of Athens, Thebes, Corinth

and Argos

, supported by the Persians, sought to escape from the hegemony, and increase their own influence. The early encounters, at Nemea

and Coronea

were typical engagements of hoplite phalanxes, resulting in Spartan victories. However, the Spartans suffered a large setback when their fleet was wiped out by a Persian Fleet at the Battle of Cnidus

, undermining the Spartan presence in Ionia. The war petered out after 394 BC, with a stalemate punctuated with minor engagements. One of these is particularly notable however; at the Battle of Lechaeum

, an Athenian force composed mostly of light troops (e.g. peltasts) defeated a Spartan regiment.

The Athenian general Iphicrates

had his troops make repeated hit and run attacks on the Spartans, who, having neither peltasts nor cavalry, could not respond effectively. The defeat of a hoplite army in this way demonstrates the changes in both troops and tactic which had occurred in Greek Warfare. The war ended when the Persians, worried by the allies' successes, changed sides, and threatened to intervene on behalf of Sparta. The peace treaty

which ended the war, effectively restored the status quo ante bellum, although Athens was permitted to retain some of the territory it had regained during the war.

The second major challenge Sparta faced was, in the event, fatal to its hegemony, and even its position as a first-rate power in Greece. As the Thebans attempted to expand their influence over Boeotia

The second major challenge Sparta faced was, in the event, fatal to its hegemony, and even its position as a first-rate power in Greece. As the Thebans attempted to expand their influence over Boeotia

, they inevitably incurred the ire of Sparta. After they refused to disband their army, an army of approximately 10,000 Spartans and Pelopennesians marched north to challenge the Thebans. At the decisive Battle of Leuctra

(371 BC), the Thebans routed the allied army. The battle is famous for the tactical innovations of the Theban general Epaminondas

.

Defying convention, he strengthened the left flank of the phalanx to an unheard of depth of 50 ranks, at the expense of the centre and the right. The centre and right were staggered backwards from the left (an 'echelon' formation), so that the phalanx advanced obliquely. The Theban left wing was thus able to crush the elite Spartan forces on the allied right, whilst the Theban centre and left avoided engagement; after the defeat of the Spartans and the death of the Spartan king, the rest of the allied army routed. This is one of the first known examples of both the tactic of local concentration of force, and the tactic of 'refusing a flank'.

Following this victory, the Thebans first secured their power-base in Boeotia, before marching on Sparta. As the Thebans were joined by many erstwhile Spartan allies, the Spartans were powerless to resist this invasion. The Thebans marched into Messenia

, and freed it from Sparta; this was a fatal blow to Sparta, since Messenia had provided most of the helots

which supported the Spartan warrior society. These events permanently reduced Spartan power and prestige, and replaced the Spartan hegemony with a Theban

one. The Theban hegemony would be short-lived however.

Opposition to it throughout the period 369-362 BC caused numerous clashes. In an attempt to bolster the Thebans' position, Epaminondas again marched on the Pelopennese in 362 BC. At Mantinea

, the largest battle ever fought between the Greek city-states occurred; most states were represented on one side or the other. Epaminondas deployed tactics similar to those at Leuctra, and again the Thebans, positioned on the left, routed the Spartans, and thereby won the battle. However, such were the losses of Theban manpower, including Epaminondas himself, that Thebes was thereafter unable to sustain its hegemony. Conversely, another defeat and loss of prestige meant that Sparta was unable to regain its primary position in Greece. Ultimately, Mantinea, and the preceding decade, severely weakened many Greek states, and left them divided and without the leadership of a dominant power.

ian kingdom in the north of Greece. Unlike the fiercely independent (and small) city-states, Macedon was a tribal kingdom, ruled by an autocratic king, and importantly, covering a larger area. Once firmly unified, and then expanded, by Phillip II, Macedon possessed the resources that enabled it to dominate the weakened and divided states in southern Greece. Between 356-342 BC Phillip conquered all city states in the vicinity of Macedon, then Thessaly

and then Thrace

.

Finally Phillip sought to establish his own hegemony over the southern Greek city-states, and after defeating the combined forces of Athens and Thebes, the two most powerful states, at the Battle of Chaeronea

in 338 BC, succeeded. Now unable to resist him, Phillip compelled most of the city states of southern Greece (including Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos; but not Sparta) to join the Corinthian League, and therefore become allied to him.

This established a lasting Macedonian hegemony over Greece, and allowed Phillip the resources and security to launch a war against the Persian Empire. After his assassination, this war was prosecuted by his son Alexander the Great, and resulted in the takeover of the whole Achaemenid Empire by the Macedonians. A united Macedonian empire did not long survive Alexander's death, and soon split into the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Diadochi

(Alexander's generals). However, these kingdoms were still enormous states, and continued to fight in the same manner as Phillip and Alexander's armies had. The rise of Macedon and her successors thus sounded the death knell for the distinctive way of war found in Ancient Greece; and instead contributed to the 'superpower' warfare which would dominate the ancient world between 350-150 BC.

Ravaging the countryside cost much effort and was also dependent on the season because green crops do not burn as well as those nearer to harvest which are more dry. War also led to acquisition of land and slaves which would lead to a greater harvest, which could support a larger army. Plunder was also a large part of war and this allowed for pressure to be taken off of the government finances and allowed for investments to be made that would strengthen the polis. War also stimulated production because of the sudden increase in demand for weapons and armor. Ship builders would also experience sudden increases in their production demands.

'. Much more lightly armoured, the Macedonian phalanx was not so much a shield-wall as a spear-wall. The Macedonian phalanx was a supreme defensive formation, but was not intended to be decisive offensively; instead, it was used to pin down the enemy infantry, whilst more mobile forces (such as cavalry) outflanked them. This 'combined arms

' approach was furthered by the extensive use of skirmisher

s, such as peltast

s.

Tactically, Phillip absorbed the lessons of centuries of warfare in Greece. He echoed the tactics of Epaminondas

at Chaeronea, by not engaging his right wing against the Thebans until his left wing had routed the Athenians; thus in course outnumbering and outflanking the Thebans, and securing victory. Alexander's fame is in no small part due to his success as a battlefield tactician; the unorthodox gambits he used at the battles of Issus

and Gaugamela

were unlike anything seen in Ancient Greece before.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

from its 'Dark Age

Greek Dark Ages

The Greek Dark Age or Ages also known as Geometric or Homeric Age are terms which have regularly been used to refer to the period of Greek history from the presumed Dorian invasion and end of the Mycenaean Palatial civilization around 1200 BC, to the first signs of the Greek city-states in the 9th...

', the population seemed to have significantly risen, allowing restoration of urbanized culture, and the rise of the city-states (Poleis). Such developments would have consequently restored the possibility of organized warfare between statelets (as opposed to e.g. cattle-raiding etc.). Although it does not necessarily follow that conflict must occur, the fractious nature of Ancient Greek society seems to have made this inevitable. Concomitant with the rise of the city-state was the evolution of a new way of warfare - the hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

phalanx

Phalanx formation

The phalanx is a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar weapons...

.

When exactly this occurred is uncertain amongst historians, but it is thought to have been created by the Spartans in around 650 BC. The hoplite was a heavily armoured, spear-armed citizen-soldier, primarily drawn from the middle classes. Fighting in the tight phalanx formation maximised the effectiveness of the armour, large shields and spears carried by the hoplites, aiming to present an impenetrable wall of men. Warfare in the archaic period seems to have mostly occurred of small-scale, set-piece battles between very similar phalanxs from the city-states in conflict. Since the soldiers were primarily citizens with other occupations, warfare was limited to seasonal, relatively local and of low-intensity. Neither side could afford heavy casualties or sustained campaigns, so conflicts seem to have been resolved by single battles.

The scale and scope of warfare in Ancient Greece changed dramatically as a result of the Greco-Persian Wars

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and city-states of the Hellenic world that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus...

. To fight the enormous armies of the Achaemenid Empire

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

was effectively beyond the capabilities of a single city-state. The eventual triumph of the Greeks was achieved by alliances of many city-states (the exact composition changing over time), allowing the pooling of resources and division of labour. Although alliances between city states occurred before this time, nothing on this scale had been seen before. The rise of Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

as pre-eminent powers during this conflict led directly to the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

, which saw further development of the nature of warfare, strategy and tactics. Fought between leagues of cities dominated by Athens and Sparta, the increased manpower and financial resources increased the scale, and allowed the diversification of warfare. Set-piece battles during the Peloponnesian war proved indecisive and instead there was increased reliance on attritionary strategies, naval battle and blockades and sieges. These changes greatly increased the number of casualties and the disruption of Greek society.

Following the eventual defeat of the Athens in 404 BC, and the disbandment of the Athenian-dominated Delian League

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in circa 477 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, members numbering between 150 to 173, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Greco–Persian Wars...

, Ancient Greece fell under the hegemony

Spartan hegemony

The city-state of Sparta was the greatest military land power of classical Greek antiquity. During the classical period, Sparta owned, dominated or influenced the entire Peloponnese. Additionally, the defeat of the Athenians and the Delian League in the Peloponnesian War in 431-404 BCE resulted in...

of Sparta. However, it was soon apparent that the hegemony was unstable, and the Persian Empire sponsored a rebellion by the combined powers of Athens, Thebes, Corinth

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

and Argos

Argos

Argos is a city and a former municipality in Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Argos-Mykines, of which it is a municipal unit. It is 11 kilometres from Nafplion, which was its historic harbour...

, resulting in the Corinthian War

Corinthian War

The Corinthian War was an ancient Greek conflict lasting from 395 BC until 387 BC, pitting Sparta against a coalition of four allied states; Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos; which were initially backed by Persia. The immediate cause of the war was a local conflict in northwest Greece in which...

(395-387 BC). After largely inconclusive campaigning, the war was decided when the Persians switched to supporting the Spartans, in return for the cities of Ionia

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

and Spartan non-interference in Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

. This brought the rebels to terms, and restored the Spartan hegemony on a more stable footing. The Spartan hegemony would last another 16 years, until, at the Battle of Leuctra

Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Boeotians led by Thebans and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae...

(371) the Spartans were decisively defeated by the Theban general Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

.

In the aftermath of this, the Thebans acted with alacrity to establish a hegemony

Theban hegemony

The Theban Hegemony lasted from the Theban victory over the Spartans at Leuctra in 371 BC to their defeat of a coalition of Peloponnesian armies at Mantinea in 362 BC, though Thebes sought to maintain its position until finally eclipsed by the rising power of Macedon in 346 BC.Externally, the way...

of their own over Greece. However, Thebes lacked sufficient manpower and resources, and became overstreched in attempting to impose itself on the rest of Greece. Following the death of Epaminondas and loss of manpower at the Battle of Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea may refer to one of three battles fought at Mantinea:*Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea...

(362 BCE), the Theban hegemony ceased. Indeed, the losses in the ten years of the Theban hegemony left all the Greek city-states weakened and divided. As such, the city-states of southern Greece would shortly afterwards be powerless to resist the rise of the Macedonian kingdom in the north. With revolutionary tactics, King Phillip II brought most of Greece under his sway, paving the way for the conquest of "the known world" by his son Alexander the Great. The rise of the Macedonian Kingdom is generally taken to signal the end of the Greek Classical period, and certainly marked the end of distinctive way of war in Ancient Greece.

Hoplite

The origins of the hoplite are obscure, and no small matter of contention amongst historians. Traditionally, this has been dated to the 8th century BCE, and attributed to Sparta; but more recent views suggest a later date, towards the 7th century BCE. Certainly, by approximately 650 BCE, as dated by the 'Chigi vase

Chigi vase

The Chigi vase is a Protocorinthian olpe, or pitcher, that is the name vase of the Chigi Painter. It was found in an Etruscan tomb at Monte Aguzzo, near Cesena, on Prince Mario Chigi’s estate in 1881. The vase has been variously assigned to the middle and late protocorinthian periods and given a...

', the 'hoplite revolution' was complete. The major innovation in the development of the hoplite seems to have been the characteristic circular shield (Aspis

Aspis

"Aspis" is the generic term for the word shield. The aspis, which is carried by Greek infantry of various periods, is often referred to as a hoplon .According to Diodorus Siculus:-Construction:...

), roughly 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter, and made of wood faced with bronze. Although very heavy (8 –), the design of this shield was such that it could be supported on the shoulder. More importantly, it permitted the formation of a shield-wall by an army, an impenetrable mass of men and shields. Men were also equipped with metal greaves and also a breast plate made of bronze, leather, or stiff cloth. When this was combined with the primary weapon of the hoplite, 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) long spear (the doru

Dory (spear)

The dory or doru - ie not pronounced like the fish - is a spear that was the chief armament of hoplites in Ancient Greece. The word "dory" is first attested in Homer with the meanings of "wood" and "spear". Homeric heroes hold two dorys...

), it gave both offensive and defensive capabilities.

Regardless of where it developed, the model for the hoplite army evidently quickly spread throughout Greece. The persuasive qualities of the phalanx were probably its relative simplicity (allowing its use by a citizen militia), low fatality rate (important for small city-states), and relatively low cost (enough for each hoplite to provide their own equipment). The Phalanx also became a source of political influence because men had to provide their own equipment in order to be a part of the army.

The hoplite phalanx

Archaic period in Greece

The Archaic period in Greece was a period of ancient Greek history that followed the Greek Dark Ages. This period saw the rise of the polis and the founding of colonies, as well as the first inklings of classical philosophy, theatre in the form of tragedies performed during Dionysia, and written...

and Classical

Classical Greece

Classical Greece was a 200 year period in Greek culture lasting from the 5th through 4th centuries BC. This classical period had a powerful influence on the Roman Empire and greatly influenced the foundation of Western civilizations. Much of modern Western politics, artistic thought, such as...

periods in Greece (approx. 750-350 BCE) was a formation in which the hoplites would line up in ranks in close order. The hoplites would lock their shields together, and the first few ranks of soldiers would project their spears out over the first rank of shields. The phalanx therefore presented a shield wall and a mass of spear points to the enemy, making frontal assaults much more difficult. It also allowed a higher proportion of the soldiers to be actively engaged in combat at a given time (rather than just those in the front rank).

When advancing towards an enemy, the phalanx would break into a run that was sufficient enough to create momentum but not too much as to lose cohesion. The opposing sides would collide viciously, possibly terrifying many of the hoplites of the front row. The battle would then rely on the valour of the men in the front line; whilst those in the rear maintained forward pressure on the front ranks with their shields. When in combat, the whole formation would consistently press forward trying to break the enemy formation; thus when two phalanx formations engaged, the struggle essentially became a pushing match, in which, as a rule, the deeper phalanx would almost always win, with few recorded exceptions.

Hoplite warfare

At least in the Archaic Period, the fragmentary nature of Ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict, but conversely limited the scale of warfare. Unable to maintain professional armies, the city-states relied on their own citizens to fight. This inevitably reduced the potential duration of campaigns, as citizens would need to return to the own professions (especially in the case of farmers). Campaigns would therefore often be restricted to summer. Armies marched directly to their target, possibly agreed on by the protagonists.If battle was refused by one side, they would retreat to the city, in which case the attackers generally had to content themselves with ravaging the countryside around, since siegecraft was undeveloped. When battles occurred, they were usually set piece and intended to be decisive. The battlefield would be flat and open, reducing the possibilities for complex tactical maneuvers. These battles were short, bloody, and brutal, and thus required a high degree of discipline. At least in the early classical period, other troops were less important; (cavalry) generally protected the flanks, when present at all; and both light infantry and missile troops were negligible.

The strength of hoplites was shock combat. The two phalanxes would smash into each other in hopes of breaking or encircling the enemy force's line. Failing that, a battle degenerated into a pushing match, with the men in the rear trying to force the front lines through those of the enemy. This maneuver was known as the Othismos. Battles rarely lasted more than an hour. Once one of the lines broke, the troops would generally flee from the field, sometimes chased by peltasts or light cavalry. If a hoplite escaped, he would sometimes be forced to drop his cumbersome aspis, thereby disgracing himself to his friends and family. Casualties were slight compared to later battles, rarely amounting to more than 5% of the losing side, but the slain often included the most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front. Thus, the whole war could be decided by a single field battle; victory was enforced by ransoming the fallen back to the defeated, called the 'Custom of the Dead Greeks'.

The Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (499-448 BC) were the result of attempts by the Persian EmperorAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

Darius the Great

Darius I of Persia

Darius I , also known as Darius the Great, was the third king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire...

, and then his successor Xerxes I

Xerxes I of Persia

Xerxes I of Persia , Ḫšayāršā, ), also known as Xerxes the Great, was the fifth king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire.-Youth and rise to power:...

to subjugate Ancient Greece. Darius was already ruler of the Greek cities of Ionia

Ionia

Ionia is an ancient region of central coastal Anatolia in present-day Turkey, the region nearest İzmir, which was historically Smyrna. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements...

, and the wars are taken to start when they rebelled in 499 BC. The revolt was crushed by 494 BC, but Darius resolved to bring mainland Greece under his dominion. Many city-states made their submission to him, but others did not, notably including Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

and Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

. Darius thus sent his commanders Datis and Artaphernes to attack Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, to punish Athens for her intransigence. After burning Eretria

Eretria

Erétria was a polis in Ancient Greece, located on the western coast of the island of Euboea, south of Chalcis, facing the coast of Attica across the narrow Euboean Gulf. Eretria was an important Greek polis in the 6th/5th century BC. However, it lost its importance already in antiquity...

, the Persians landed at Marathon

Marathon, Greece

Marathon is a town in Greece, the site of the battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the heavily outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians. The tumulus or burial mound for the 192 Athenian dead that was erected near the battlefield remains a feature of the coastal plain...

.

An Athenian army of c. 10,000 hoplites marched to meet Persian army of c. 20-60,000. The Athenians were at a significant disadvantage both strategically and tactically. Raising such a large army had denuded Athens of defenders, and thus any attack in the Athenian rear would cut off the Army from the City. Tactically, the hoplites were very vulnerable to attacks by cavalry , and the Athenians had no cavalry to defend the flanks. After several days of stalemate at Marathon, the Persian commanders attempted to take strategic advantage by sending their cavalry (by ship) to raid Athens itself. This gave the Athenian army a small window of opportunity to attack the remainder of the Persian Army.

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

between a hoplite army and a non-Greek army. The Persians had acquired a reputation for invincibility, but the Athenian hoplites proved crushingly superior in the ensuing infantry battle. To counter the massive numbers of Persians, the Greek general Miltiades

Miltiades

Miltiades or Miltiadis is a Greek name. Several historic persons have been called Miltiades .* Miltiades the Elder wealthy Athenian, and step-uncle of Miltiades the Younger...

ordered the troops to be spread across an unusually wide front, leaving the centre of the Greek line undermanned. However, the lightly armoured Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured hoplites, and the Persian wings were quickly routed. The Greek wings then turned against the elite troops in the Persian centre, which had held the Greek centre until then. Marathon demonstrated to the Greeks the lethal potential of the hoplite, and firmly demonstrated that the Persians were not, after all, invincible.

The revenge of the Persians was postponed 10 years by internal conflicts in the Persian Empire, until Darius's son Xerxes returned to Greece in 480 BC with a staggeringly large army (modern estimates suggest between 150,000-250,000 men). Many Greeks city-states, having had plenty of warning of the forthcoming invasion, formed an anti-Persian league; though as before, other city-states remained neutral or allied with Persia. Although alliances between city-states were commonplace, the scale of this league was a novelty, and the first time that the Greeks had united in such a way to face an external threat.

This allowed diversification of the allied armed forces, rather than simply mustering a very large hoplite army. The visionary Athenian politician Themistocles

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

had successfully persuaded his fellow citizens to build a huge fleet in 483/82 BC to combat the Persian threat (and thus to effectively abandon their hoplite army, since there were not men enough for both). Amongst the allies therefore, Athens was able to form the core of a navy, whilst other cities, including of course Sparta, provided the army. This alliance thus removed the constraints on the type of armed forces that the Greeks could use. The use of such a large navy was also a novelty to the Greeks.

The second Persian invasion is famous for the battles of Thermopylae

Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, led by King Leonidas of Sparta, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium, in August...

and Salamis

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

. As the massive Persian army moved south through Greece, the allies sent a small holding force (c. 10,000) men under the Spartan king Leonidas, to block the pass of Thermopylae

Thermopylae

Thermopylae is a location in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur springs. "Hot gates" is also "the place of hot springs and cavernous entrances to Hades"....

whilst the main allied army could be assembled. The allied navy extended this blockade at sea, blocking the nearby straits of Artemisium

Artemisium

Artemisium is a cape north of Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of a debatable Zeus or Poseidon was found off this cape in a sunken ship.-See also:* Temple of Artemis...

, to prevent the huge Persian navy landing troops in Leonidas's rear. Famously, Leonidas's men held the much larger Persian army at the pass (where their numbers counted for nothing) for three days, the hoplites again proving their superiority.

Only when a Persian force managed to outflank them by means of a mountain track was the allied army overcome; but by then Leonidas dismissed the majority of the troops, remaining with 300 Spartans (and perhaps 2000 other troops) to guard the pass, in the process making one of history's great last stands. The Greek navy, despite their lack of experience, also proved their worth holding back the Persian fleet whilst the army still held the pass.

Thermopylae provided the Greeks with time to arrange their defences, and they dug in across the Isthmus of Corinth

Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The word "isthmus" comes from the Ancient Greek word for "neck" and refers to the narrowness of the land. The Isthmus was known in the ancient...

, an impregnable position; although an evacuated Athens was thereby sacrificed to the advancing Persians. In order to outflank the isthmus, Xerxes needed to use this fleet, and in turn therefore needed to defeat the Greek fleet; similarly, the Greeks needed to neutralise the Persian fleet to ensure their safety. To this end, the Greeks were able to lure the Persian fleet into the straits of Salamis

Salamis Island

Salamis , is the largest Greek island in the Saronic Gulf, about 1 nautical mile off-coast from Piraeus and about 16 km west of Athens. The chief city, Salamina , lies in the west-facing core of the crescent on Salamis Bay, which opens into the Saronic Gulf...

; and, in a battleground where Persian numbers again counted for nothing, they won a decisive victory

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

, justifying Themistocle's decision to build the Athenian fleet. Demoralised, Xerxes returned to Asia Minor with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius

Mardonius

Mardonius was a leading Persian military commander during the Persian Wars with Greece in the early 5th century BC.-Early years:Mardonius was the son of Gobryas, a Persian nobleman who had assisted the Achaemenid prince Darius when he claimed the throne...

to campaign in Greece the following year (479 BC).

However, a united Greek army of c. 40,000 hoplites decisively defeated Mardonius at the Battle of Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

, effectively ending the invasion. Almost simultaneously, the allied fleet defeated the remnants of the Persian navy at Mycale

Battle of Mycale

The Battle of Mycale was one of the two major battles that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece during the Greco-Persian Wars. It took place on or about August 27, 479 BC on the slopes of Mount Mycale, on the coast of Ionia, opposite the island of Samos...

, thus destroying the Persian hold on the islands of the Aegean

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

.

The remainder of the wars saw the Greeks take the fight to the Persians. The Athenian dominated Delian League

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in circa 477 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, members numbering between 150 to 173, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Greco–Persian Wars...

of cities and islands extirpated Persian garrisons from Macedon

Macedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

and Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

, before eventually freeing the Ionian cities from Persian rule. At one point, the Greeks even attempted an invasion of Cyprus and Egypt (which proved disastrous)), demonstrating a major legacy of the Persian Wars: warfare in Greece had moved beyond the seasonal squabbles between city-states, to coordinated international actions involving huge armies. The ambitions of many Greek states had dramatically increased, and the tensions resulting from this would lead directly onto the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

.

The Peloponnesian War

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in circa 477 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, members numbering between 150 to 173, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Greco–Persian Wars...

and the Spartan dominated Peloponnesian League

Peloponnesian League

The Peloponnesian League was an alliance in the Peloponnesus from the 6th to the 4th centuries BC.- Early history:By the end of the 6th century, Sparta had become the most powerful state in the Peloponnese, and was the political and military hegemon over Argos, the next most powerful state...

. Whatever the proximal causes of the war, it was in essence a conflict between Athens and Sparta for supremacy in Greece. The war (or wars, since it is often divided into three periods) was for much of the time a stalemate, punctuated with occasional bouts of activity. Tactically the Peloponnesian war represents something of a stagnation; the strategic elements were most important as the two sides tried to break the deadlock, something of a novelty in Greek warfare.

Building on the experience of the Persian Wars, the diversification from core hoplite warfare, permitted by increased resources, continued. There was increased emphasis on navies, sieges, mercenaries and economic warfare. Far from the previously limited and formalized form of conflict, the Peloponnesian War transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with atrocities on a large scale; shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside and destroying whole cities.

From the start, the mismatch in the opposing forces was clear. The Delian League (hereafter 'Athenians') were primarily a naval powers, whereas the Peloponnesian League (hereafter 'Spartans') consisted of primarily land-based powers. The Athenians thus avoided battle on land, since they could not possibly win, and instead dominated the sea, blockading the Peloponnesus whilst maintaining their own trade. Conversely, the Spartans repeatedly invaded Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, but only for a few weeks at a time; they remained wedded to the idea of hoplite-as-citizen. Although both sides suffered setbacks and victories, the first phase essentially ended in stalemate, as neither league had the power to neutralise the other. The second phase, an Athenian expedition to attack Syracuse

Syracuse, Italy

Syracuse is a historic city in Sicily, the capital of the province of Syracuse. The city is notable for its rich Greek history, culture, amphitheatres, architecture, and as the birthplace of the preeminent mathematician and engineer Archimedes. This 2,700-year-old city played a key role in...

in Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

achieved no tangible result other than a large loss of Athenian ships and men.

In the third phase of the war however the use of more sophisticated stratagems eventually allowed the Spartans to force Athens to surrender. Firstly, the Spartans permanently garrisoned a part of Attica, removing from Athenian control the silver mine which funded the war effort. Forced to squeeze even more money from her allies, the Athenian league thus became heavily strained. After the loss of Athenian ships and men in the Sicilian expedition, Sparta was able to foment rebellion amongst the Athenian league, which therefore massively reduced the ability of the Athenians to continue the war.

Athens in fact partially recovered from this setback between 410-406 BC, but a further act of economic war finally forced her defeat. Having developed a navy that was capable of taking on the much-weakened Athenian navy, the Spartan general Lysander

Lysander

Lysander was a Spartan general who commanded the Spartan fleet in the Hellespont which defeated the Athenians at Aegospotami in 405 BC...

seized the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain. The remaining Athenian fleet was thereby forced to confront the Spartans, and were decisively defeated. Athens had little choice but to surrender; and was stripped of her city walls, overseas possessions and navy. In the aftermath, the Spartans were able to establish themselves as the dominant force in Greece for three decades.

Mercenaries and light infantry

Although tactically there was little innovation in the Peloponessian War, there does appear to have been an increase in the use of light infantry, such as peltastPeltast

A peltast was a type of light infantry in Ancient Thrace who often served as skirmishers.-Description:Peltasts carried a crescent-shaped wicker shield called pelte as their main protection, hence their name. According to Aristotle the pelte was rimless and covered in goat or sheep skin...

s (javelin throwers) and archers. Many of these would have been mercenary troops, hired from outlying regions of Greece. For instance, the Agrianes

Agrianes

The Agrianians a Paeonian-Thracian tribe, who chiefly inhabited the area of present-day Northeastern statistical region of Republic Of Macedonia and Pčinja District of southern Serbia, north of the Thracian Maedi tribe, who were situated in what is now the Greek region of Macedonia and Western...

from Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

were well-renowned peltasts, whilst Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

was famous for its archers. Since there were no decisive land-battles in the Peloponnesian War, the presence or absence of these troops was unlikely to have affected the course of the war. Nevertheless, it was in important innovation, one which was developed much further in later conflicts.

Spartan & Theban hegemonies

The peace treaty which ended the Peloponnesian War left Sparta as the de facto ruler of Greece (hegemon). Although the Spartans did not attempt to rule all of Greece directly, they prevented alliances of other Greek cities, and forced the city-states to accept governments deemed suitable by Sparta. However, from the very beginning, it was clear that the Spartan hegemony was shaky; the Athenians, despite their crushing defeat, restored their democracy but just one year later, ejecting the Sparta-approved oligarchyOligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

. The Spartans did not feel strong enough to impose their will on a shattered Athens. Undoubtedly part of the reason for the weakness of the hegemony was a decline in the Spartan population.

The first major challenge to the Spartan hegemony occurred in the Corinthian War

Corinthian War

The Corinthian War was an ancient Greek conflict lasting from 395 BC until 387 BC, pitting Sparta against a coalition of four allied states; Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos; which were initially backed by Persia. The immediate cause of the war was a local conflict in northwest Greece in which...

(395-387 BC). Sensing the Spartan weakness, an alliance of Athens, Thebes, Corinth

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

and Argos

Argos

Argos is a city and a former municipality in Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Argos-Mykines, of which it is a municipal unit. It is 11 kilometres from Nafplion, which was its historic harbour...

, supported by the Persians, sought to escape from the hegemony, and increase their own influence. The early encounters, at Nemea

Battle of Nemea

The Battle of Nemea was a battle in the Corinthian War, between Sparta and the allied cities of Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes. The battle was fought in Corinthian territory, at the dry bed of the Nemea River...

and Coronea

Battle of Coronea (394 BC)

The Battle of Coronea in 394 BC was a battle in the Corinthian War, in which the Spartans and their allies under King Agesilaus II defeated a force of Thebans and Argives that was attempting to block their march back into the Peloponnese.-Prelude:...

were typical engagements of hoplite phalanxes, resulting in Spartan victories. However, the Spartans suffered a large setback when their fleet was wiped out by a Persian Fleet at the Battle of Cnidus

Battle of Cnidus

The Battle of Cnidus , was a joint Athenian and Persian operation against the Spartan naval fleet in the Corinthian War. A combined Athenian-Persian fleet, led by the former Greek admiral Conon, destroyed the Spartan fleet led by the inexperienced Peisander, ending Sparta's brief bid for naval...

, undermining the Spartan presence in Ionia. The war petered out after 394 BC, with a stalemate punctuated with minor engagements. One of these is particularly notable however; at the Battle of Lechaeum

Battle of Lechaeum

The Battle of Lechaeum was an Athenian victory in the Corinthian War. In the battle, the Athenian general Iphicrates took advantage of the fact that a Spartan hoplite regiment operating near Corinth was moving in the open without the protection of any missile throwing troops. He decided to ambush...

, an Athenian force composed mostly of light troops (e.g. peltasts) defeated a Spartan regiment.

The Athenian general Iphicrates

Iphicrates

Iphicrates was an Athenian general, the son of a shoemaker, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC....

had his troops make repeated hit and run attacks on the Spartans, who, having neither peltasts nor cavalry, could not respond effectively. The defeat of a hoplite army in this way demonstrates the changes in both troops and tactic which had occurred in Greek Warfare. The war ended when the Persians, worried by the allies' successes, changed sides, and threatened to intervene on behalf of Sparta. The peace treaty

Peace of Antalcidas

The Peace of Antalcidas , also known as the King's Peace, was a peace treaty guaranteed by the Persian King Artaxerxes II that ended the Corinthian War in ancient Greece. The treaty's alternate name comes from Antalcidas, the Spartan diplomat who traveled to Susa to negotiate the terms of the...

which ended the war, effectively restored the status quo ante bellum, although Athens was permitted to retain some of the territory it had regained during the war.

Boeotia

Boeotia, also spelled Beotia and Bœotia , is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. It was also a region of ancient Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, the second largest city being Thebes.-Geography:...

, they inevitably incurred the ire of Sparta. After they refused to disband their army, an army of approximately 10,000 Spartans and Pelopennesians marched north to challenge the Thebans. At the decisive Battle of Leuctra

Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Boeotians led by Thebans and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae...

(371 BC), the Thebans routed the allied army. The battle is famous for the tactical innovations of the Theban general Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

.

Defying convention, he strengthened the left flank of the phalanx to an unheard of depth of 50 ranks, at the expense of the centre and the right. The centre and right were staggered backwards from the left (an 'echelon' formation), so that the phalanx advanced obliquely. The Theban left wing was thus able to crush the elite Spartan forces on the allied right, whilst the Theban centre and left avoided engagement; after the defeat of the Spartans and the death of the Spartan king, the rest of the allied army routed. This is one of the first known examples of both the tactic of local concentration of force, and the tactic of 'refusing a flank'.

Following this victory, the Thebans first secured their power-base in Boeotia, before marching on Sparta. As the Thebans were joined by many erstwhile Spartan allies, the Spartans were powerless to resist this invasion. The Thebans marched into Messenia

Messenia

Messenia is a regional unit in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, one of 13 regions into which Greece has been divided by the Kallikratis plan, implemented 1 January 2011...

, and freed it from Sparta; this was a fatal blow to Sparta, since Messenia had provided most of the helots

Helots

The helots: / Heílôtes) were an unfree population group that formed the main population of Laconia and the whole of Messenia . Their exact status was already disputed in antiquity: according to Critias, they were "especially slaves" whereas to Pollux, they occupied a status "between free men and...

which supported the Spartan warrior society. These events permanently reduced Spartan power and prestige, and replaced the Spartan hegemony with a Theban

Theban hegemony

The Theban Hegemony lasted from the Theban victory over the Spartans at Leuctra in 371 BC to their defeat of a coalition of Peloponnesian armies at Mantinea in 362 BC, though Thebes sought to maintain its position until finally eclipsed by the rising power of Macedon in 346 BC.Externally, the way...

one. The Theban hegemony would be short-lived however.

Opposition to it throughout the period 369-362 BC caused numerous clashes. In an attempt to bolster the Thebans' position, Epaminondas again marched on the Pelopennese in 362 BC. At Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea

Battle of Mantinea may refer to one of three battles fought at Mantinea:*Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea *Battle of Mantinea...

, the largest battle ever fought between the Greek city-states occurred; most states were represented on one side or the other. Epaminondas deployed tactics similar to those at Leuctra, and again the Thebans, positioned on the left, routed the Spartans, and thereby won the battle. However, such were the losses of Theban manpower, including Epaminondas himself, that Thebes was thereafter unable to sustain its hegemony. Conversely, another defeat and loss of prestige meant that Sparta was unable to regain its primary position in Greece. Ultimately, Mantinea, and the preceding decade, severely weakened many Greek states, and left them divided and without the leadership of a dominant power.

The end of the hoplite era

Although by the end of the Theban hegemony the cities of Greece were severely weakened, they might have risen again had it not been for the ascent to power of the MacedonMacedon

Macedonia or Macedon was an ancient kingdom, centered in the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula, bordered by Epirus to the west, Paeonia to the north, the region of Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south....

ian kingdom in the north of Greece. Unlike the fiercely independent (and small) city-states, Macedon was a tribal kingdom, ruled by an autocratic king, and importantly, covering a larger area. Once firmly unified, and then expanded, by Phillip II, Macedon possessed the resources that enabled it to dominate the weakened and divided states in southern Greece. Between 356-342 BC Phillip conquered all city states in the vicinity of Macedon, then Thessaly

Thessaly

Thessaly is a traditional geographical region and an administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thessaly was known as Aeolia, and appears thus in Homer's Odyssey....

and then Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

.

Finally Phillip sought to establish his own hegemony over the southern Greek city-states, and after defeating the combined forces of Athens and Thebes, the two most powerful states, at the Battle of Chaeronea

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between the forces of Philip II of Macedon and an alliance of Greek city-states...

in 338 BC, succeeded. Now unable to resist him, Phillip compelled most of the city states of southern Greece (including Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos; but not Sparta) to join the Corinthian League, and therefore become allied to him.

This established a lasting Macedonian hegemony over Greece, and allowed Phillip the resources and security to launch a war against the Persian Empire. After his assassination, this war was prosecuted by his son Alexander the Great, and resulted in the takeover of the whole Achaemenid Empire by the Macedonians. A united Macedonian empire did not long survive Alexander's death, and soon split into the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Diadochi

Diadochi

The Diadochi were the rival generals, family and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for the control of Alexander's empire after his death in 323 BC...

(Alexander's generals). However, these kingdoms were still enormous states, and continued to fight in the same manner as Phillip and Alexander's armies had. The rise of Macedon and her successors thus sounded the death knell for the distinctive way of war found in Ancient Greece; and instead contributed to the 'superpower' warfare which would dominate the ancient world between 350-150 BC.

The effect of war on the economy

Campaigns were often timed with the agricultural season so as to impact the enemy's or enemies' crops and harvest. The timing had to be very carefully arranged so that the invaders' enemy's harvest would be disrupted but the invaders' harvest would not be affected. Late invasions were also possible in the hopes that the sowing season would be affected but this at best would have minimal effects on the harvest. One alternative to disrupting the harvest was to ravage the countryside by uprooting trees, burning houses and crops and killing all who were not safe behind the walls of the city.Ravaging the countryside cost much effort and was also dependent on the season because green crops do not burn as well as those nearer to harvest which are more dry. War also led to acquisition of land and slaves which would lead to a greater harvest, which could support a larger army. Plunder was also a large part of war and this allowed for pressure to be taken off of the government finances and allowed for investments to be made that would strengthen the polis. War also stimulated production because of the sudden increase in demand for weapons and armor. Ship builders would also experience sudden increases in their production demands.

The innovations of Phillip II

One major reason for Phillip's success in conquering Greece was the break with Hellenic military traditions that he made. With more resources available, he was able to assemble a more diverse army, including strong cavalry components. He took the development of the phalanx to its logical completion, arming his 'phalangites' (for they were assuredly not hoplites) with a fearsome 6 m (19.7 ft) pike, the 'sarissaSarissa