Aeneas Mackintosh

Encyclopedia

Aeneas Lionel Acton Mackintosh (1 July 1879 – 8 May 1916) was a British Merchant Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, who commanded the Ross Sea party

as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

, 1914–17. The Ross Sea party's mission was to support Shackleton's proposed transcontinental march by laying supply depots along the latter stages of the march's intended route. In the face of persistent setbacks and practical difficulties, Mackintosh's party fulfilled its task, although Mackintosh and two others died in the course of their duties.

Mackintosh's first Antarctic experience was as second officer

on Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition

, 1907–09. Shortly after his arrival in the Antarctic a shipboard accident destroyed his right eye, and he was sent back to New Zealand. He returned in 1909 to participate in the later stages of the expedition; his will and determination in adversity impressed Shackleton, and led to his Ross Sea party appointment in 1914.

Mackintosh's operational orders were confused through communication failures, and he was uncertain of the timing of Shackleton's proposed march. His difficulties were compounded when the party's ship, SY Aurora, was swept from its winter moorings during a gale and was unable to return. Despite this loss of equipment, supplies and personnel, Mackintosh and his stranded shore party managed to carry out its depot-laying task to the full. Mackintosh himself barely survived the ordeal, owing his life to the actions of his comrades. He and one companion then attempted to cross the 13 nmi (24.1 km; 15 mi) of sea ice separating the party from its base, but the pair disappeared during a blizzard

and are presumed to have fallen through the ice. Their bodies were never recovered.

Mackintosh's competence, and his shortcomings as a leader, have been questioned by commentators. Shackleton himself commended the work of Mackintosh and his comrades, and equated the sacrifice of their lives to those given in the trenches of the First World War. At the same time he was critical of Mackintosh's organising skills. Years later, Shackleton's son, Lord Shackleton, identified Mackintosh as one of the expedition's heroes, alongside Ernest Joyce

and Dick Richards.

, India

, on 1 July 1879, one of six children (five sons and a daughter) of Scottish indigo planter, Alexander Mackintosh, a descendent of the chieftains of Clan Chattan

. Aeneas would in due course be named as an heir to the chieftainship, and to the ancient seat at Inverness

that went with it. His privileged expatriate background and "cut-glass diction" led his friend and fellow Antarctic captain John King Davis

to describe him as a "sahib"

. When Mackintosh was still a young child his mother, Annie Mackintosh, suddenly returned to Britain, bringing the children with her, and the father thereafter disappears from the family story. At home in Bedfordshire, Mackintosh attended Bedford Modern School

. He then followed the same path as had Shackleton five years earlier, leaving school aged 16 to go to sea. After serving a tough Merchant Officer's apprenticeship he joined the P and O Line

, remaining with this company until recruited by Shackleton in 1907, as second officer on Nimrod, bound for Antarctica. He was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant

in the Royal Naval Reserve

in 1908.

The Nimrod Expedition

The Nimrod Expedition

, 1907–1909, was the first of three Antarctic expeditions led by Ernest Shackleton. Its ambitious objective, as stated by Shackleton, was to "proceed to the Ross Quadrant of the Antarctic with a view to reaching the Geographical South Pole

and the South Magnetic Pole

". It is possible that Shackleton approached the P & O line for suitable officers, and that Mackintosh was recommended to him. Mackintosh evidently jumped at the chance to join the expedition, and soon earned Shackleton's confidence while impressing his fellow-officers with his will and determination. While the expedition was in New Zealand Shackleton added Mackintosh to the shore party.

operated to remove the eye, using partly improvised surgical equipment. Marshall was deeply impressed by Mackintosh's fortitude, observing that "no man could have taken it better." The accident cost Mackintosh his place on the shore party, and required his return to New Zealand for further treatment. He took no part in the main events of the expedition, but returned south with Nimrod in January 1909, to participate in the closing stages. Shackleton, who had earlier fallen out with the ship's master, Rupert England, had wanted Mackintosh to captain Nimrod on this second voyage south, but the eye injury had not healed sufficiently to make this appointment possible.

. Mackintosh decided that he would lead a party in a march across the ice, to carry the mails ashore. Historian Beau Riffenburgh

describes the journey that followed as "one of the most ill-considered parts of the entire expedition".

The party, which left the ship on the morning of 3 January, consisted of Mackintosh and three sailors, with a sledge containing supplies and a large postbag. Two sailors quickly returned to the ship, while Mackintosh and one companion went forward. They camped on the ice that evening, only to find next day that the whole area around them had broken up. After a desperate dash over the moving floes they managed to reach a small glacier

tongue, where they camped and waited for several days for their snow-blindness

to subside. When their vision returned, they found that Cape Royds was in sight but inaccessible, as the sea-ice leading to it had gone. After a further wait, they decided to make for the hut by land, a dangerous undertaking without appropriate equipment and experience.

On 11 January they set out. The next 48 hours involved a perpetual struggle over the hostile terrain, through regions of deep crevasses and treacherous snowfields. They soon parted company with all their equipment and supplies. At one point, in order to proceed, they had to ascend to 3000 feet (914.4 m) and then slide to the foot of a snow-slope. After another 24 hours of stumbling around in the fog, by chance they encountered Bernard Day, a member of the shore party, a short distance from the hut. The ship later recovered the abandoned postbag. John King Davis, then serving as Nimrod's chief officer, remarked that "Mackintosh was always the man to take the hundredth chance. This time he got away with it."

Mackintosh then joined Ernest Joyce and others on a journey across the Great Ice Barrier

to Minna Bluff

, to lay a depot for Shackleton's polar party, whose return from their southern march was awaited. On 3 March, while keeping watch on the deck of Nimrod, Mackintosh observed a flare which signaled the safe arrival of Shackleton.

(who had served as a geologist on the Nimrod Expedition and was later to lead the Australasian Antarctic Expedition

) on a trip to Hungary, to survey a potential goldfield which Shackleton was hoping would form the basis of a lucrative business venture. Despite a promising report from Mawson nothing came of this. Mackintosh later launched his own treasure-hunting expedition to Cocos Island

off the Panama

Pacific coast, but again returned home empty-handed.

In February 1912 Mackintosh married Gladys Campbell, and settled into an office job as assistant secretary to the Imperial Merchant Service Guild in Liverpool

. The safe, routine work did not satisfy him: "I am still existing at this job, stuck in a dirty office," he wrote to a former Nimrod shipmate. "I always feel I never completed my first initiation—so would like to have one final wallow, for good or bad!"

a group of six led by Shackleton would march across the continent, via the South Pole. A separate Ross Sea party, based on the opposite side of the continent in McMurdo Sound

, would lay supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier and would assist the transcontinental party on the final stages of its journey. Mackintosh was originally to be a member of the crossing party, but difficulties arose over the appointment of a commander for the Ross Sea party. Eric Marshall, the surgeon from the Nimrod expedition, turned the assignmemt down, as did John King Davis; Shackleton's efforts to obtain from the Admiralty

a naval crew for this part of the enterprise were rejected. Consequently the post of Ross Sea party leader was offered to Mackintosh. His ship would be the Aurora, lately used by Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition and presently lying in Australia. Shackleton considered the Ross Sea party's assignment routine, and saw no special difficulties in its execution.

Mackintosh arrived in Australia in October 1914 to take up his duties, and was immediately faced with major problems. Without warning, Shackleton had cut the Ross Sea party's allocated funds from £2,000 (current value £) to £1,000; Mackintosh was instructed to "get whatever you can free as gifts", and to mortgage the expedition's ship to raise further money. It then emerged that the purchase of Aurora had not been properly completed, which delayed Mackintosh's attempts to mortgage it. Worse, Aurora was quite unfit for Antarctic work without an extensive overhaul, which required co-operation from an exasperated Australian Government. The tasks of dealing with these difficulties within a very restricted timescale caused Mackintosh great anxiety, and the ensuing muddles together with public relations failures created among the Australian public "an unpleasant feeling with regard to the Expedition", according to the party's chief scientist Alexander Stevens. Some members of the party resigned, others were dismissed; recruiting a full complement of crew and scientific staff involved some last-minute appointments which left the party noticeably short of Antarctic experience.

Shackleton had given Mackintosh the impression that he would attempt his crossing during the coming 1914–15 Antarctic season, if possible. Before departing for the Weddell Sea Shackleton had evidently changed his mind about the feasibility of this. According to Daily Chronicle

correspondent Ernest Perris, Mackintosh's instructions should have been corrected by cable, but this was never sent. The result of this misunderstanding was the chaotic depot-laying journeys of January–March 1915.

, Tasmania

, on 24 December 1914, and on 16 January 1915 had reached McMurdo Sound where Mackntosh established its base at Captain Scott's old headquarters at Cape Evans

. Believing that Shackleton might have already begun his march from the Weddell Sea, Mackintosh was determined that depots should be laid at 79° and 80°S, and that the work should begin at once. Ernest Joyce, the expedition's most seasoned Antarctic traveller—he had been with Scott's Discovery Expedition

in 1901–04, and with the Nimrod Expedition in 1907–09—protested that the party needed time for acclimatization and training, but was overruled. Joyce had expected that Mackintosh would defer to him on sledging matters: "If I had Shacks here I would make him see my way of arguing", he wrote in his diary. The depot-laying journey which followed began with a series of mishaps. A blizzard delayed their start, a motor sledge broke down after a few miles, and Mackintosh and his group lost their way on the sea ice between Cape Evans and Hut Point. Conditions on the Barrier were harsh for the untrained and inexperienced men. Many of the stores taken on to the Barrier were dumped on the ice to reduce loads and did not reach the depots. After Mackintosh insisted on taking the dogs the full distance to 80°S—over Joyce's urgent protests—all died on the return journey. The men, frostbitten and exhausted, reached Hut Point on 24 March, cut off from the ship and from their Cape Evans base by unsafe sea ice. After this experience confidence in Mackintosh's leadership was low, and bickering rife.

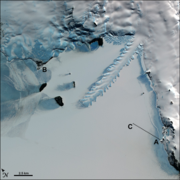

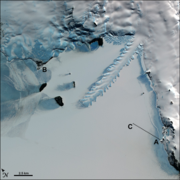

When Mackintosh and the depot-laying party finally returned to Cape Evans in mid-June they learned that their ship Aurora, with 18 on board and carrying most of the shore party's supplies and equipment, had broken loose from its winter mooring during a gale. Ice conditions in McMurdo Sound made it unlikely that the ship could return; the shore party of ten was effectively marooned with drastically depleted resources. Despite this change in circumstances Mackintosh resolved that the next season's depot-laying journeys would have to be fully carried out. The weakened party would seek to make up its shortfall in supplies and equipment by salvaging what had been left from earlier expeditions, particularly from Captain Scott's recent sojourn at Cape Evans. The entire party pledged its support to this effort, though it would require, wrote Mackintosh, a record-breaking feat of polar travel to accomplish it. Subsequently Joyce, together with Ernest Wild

When Mackintosh and the depot-laying party finally returned to Cape Evans in mid-June they learned that their ship Aurora, with 18 on board and carrying most of the shore party's supplies and equipment, had broken loose from its winter mooring during a gale. Ice conditions in McMurdo Sound made it unlikely that the ship could return; the shore party of ten was effectively marooned with drastically depleted resources. Despite this change in circumstances Mackintosh resolved that the next season's depot-laying journeys would have to be fully carried out. The weakened party would seek to make up its shortfall in supplies and equipment by salvaging what had been left from earlier expeditions, particularly from Captain Scott's recent sojourn at Cape Evans. The entire party pledged its support to this effort, though it would require, wrote Mackintosh, a record-breaking feat of polar travel to accomplish it. Subsequently Joyce, together with Ernest Wild

, was to the fore in improvising clothing, footwear and equipment from Scott's abandoned materials. However, these long winter months were difficult times for Mackintosh. Lacking the presence of a fellow-officer, he found it hard to form close relationships with his companions. His position became increasingly isolated, and subject to the increasingly vocal criticisms of Joyce in particular.

, at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. A large forward base was then established at the Bluff depot, just north of 79°, from which the final journeys to Mount Hope would be launched early in 1916. During these early stages Mackintosh clashed repeatedly with Joyce over methods. In a showdown on 28 November, confronted with incontrovertible evidence of the greater effectiveness of Joyce's methods over his own, Mackintosh was forced to back down and accept a revised plan drafted by Joyce and Richards. Joyce's private comment was "I never in my experience came across such an idiot in charge of men."

The main march southward from the Bluff depot began on 1 January 1916. Within a few days one team of three was forced to return to base, following the failure of their Primus stove. The other six carried on; the 80° depot laid the previous season was reinforced, and new depots were built at 81° and 82°. As the party moved on towards the vicinity of Mount Hope, both Mackintosh and Arnold Spencer-Smith

The main march southward from the Bluff depot began on 1 January 1916. Within a few days one team of three was forced to return to base, following the failure of their Primus stove. The other six carried on; the 80° depot laid the previous season was reinforced, and new depots were built at 81° and 82°. As the party moved on towards the vicinity of Mount Hope, both Mackintosh and Arnold Spencer-Smith

were hobbling. Shortly after the 83° mark was passed, Spencer-Smith collapsed and was left in a tent while the others struggled on the remaining few miles. Mackintosh rejected the suggestion that he should remain with the invalid, insisting that it was his duty to ensure that every depot was laid. On 26 January Mount Hope was attained and the final depot put in place.

On the homeward march Spencer-Smith had to be drawn on the sledge. Mackintosh's condition was deteriorating rapidly; unable to pull, he staggered alongside, crippled by the growing effects of scurvy. As his condition worsened, Mackintosh was forced from time to time to join Spencer-Smith as a passenger on the sledge. Even the fitter members of the group were handicapped by frostbite, snow-blindness and, increasingly, scurvy, as the journey became a desperate struggle for survival. On 8 March Mackintosh volunteered to remain in the tent while the others tried to get Spencer-Smith to the relative safety of Hut Point. Spencer-Smith died the next day. Richards, Wild and Joyce struggled on to Hut Point with the now stricken Hayward, before returning to rescue Mackintosh. By 18 March all five survivors were recuperating at Hut Point, having completed what Shackleton's biographers Marjory and James Fisher as "one of the most remarkable, and apparently impossible, feats of endurance in the history of polar travel."

With the help of fresh seal meat which halted the ravages of scurvy, the survivors slowly recovered at Hut Point. The unstable condition of the sea ice in McMurdo Sound prevented them from completing the journey to the Cape Evans base. Conditions at Hut Point were gloomy and depressing, with an unrelieved diet and no normal comforts; Mackintosh in particular found the squalor of the hut intolerable, and dreaded the possibility that, caught at Hut Point, they might miss the return of the ship. On 8 May 1916, after carrying out reconnaissance on the state of the sea ice, Mackintosh announced that he and Hayward were prepared to risk the walk to Cape Evans. Against the urgent advice of their comrades they set off, carrying only light supplies. Shortly after they had moved out of sight of Hut Point a severe blizzard developed which lasted for two days. When it had subsided, Joyce and Richards followed the still visible footmarks on the ice up to a large crack, where the tracks stopped. Neither Mackintosh nor Hayward arrived at Cape Evans and no trace of either was ever found, despite extensive searches carried out by Joyce after he, Richards and Wild finally managed to reach Cape Evans in June. After Aurora finally returned to Cape Evans in January 1917 there were further searches, equally fruitless. All the indications were that Mackintosh and Hayward had either fallen through the ice, or that the ice on which they had been walking had been blown out to sea during the blizzard.

With the help of fresh seal meat which halted the ravages of scurvy, the survivors slowly recovered at Hut Point. The unstable condition of the sea ice in McMurdo Sound prevented them from completing the journey to the Cape Evans base. Conditions at Hut Point were gloomy and depressing, with an unrelieved diet and no normal comforts; Mackintosh in particular found the squalor of the hut intolerable, and dreaded the possibility that, caught at Hut Point, they might miss the return of the ship. On 8 May 1916, after carrying out reconnaissance on the state of the sea ice, Mackintosh announced that he and Hayward were prepared to risk the walk to Cape Evans. Against the urgent advice of their comrades they set off, carrying only light supplies. Shortly after they had moved out of sight of Hut Point a severe blizzard developed which lasted for two days. When it had subsided, Joyce and Richards followed the still visible footmarks on the ice up to a large crack, where the tracks stopped. Neither Mackintosh nor Hayward arrived at Cape Evans and no trace of either was ever found, despite extensive searches carried out by Joyce after he, Richards and Wild finally managed to reach Cape Evans in June. After Aurora finally returned to Cape Evans in January 1917 there were further searches, equally fruitless. All the indications were that Mackintosh and Hayward had either fallen through the ice, or that the ice on which they had been walking had been blown out to sea during the blizzard.

. The two main sources available to Ross Sea party historians are Joyce's diaries, published in 1929 as The South Polar Trail, and the account of Dick Richards: The Ross Sea Shore Party 1914–17. Mackintosh's reputation is not well-served by either, particularly Joyce's partisan record, described by one commentator as his "self-aggrandizing epic". Joyce is generally scathing about Mackintosh's leadership; Richards's account is much shorter and more straightforward, although decades later, when he was the only member of the expedition still alive (he died in 1985, aged 91), he spoke out, claiming that Mackintosh on the depot-laying march was "tremendously pathetic", had "lost his nerve completely", and that the fatal ice walk was "suicide".

The circumstances of Mackintosh's death have led commentators to emphasise his impetuousness and incompetence. This generally negative view of him was not, however, unanimous among his comrades. Alexander Stevens, who was the Ross Sea party's chief scientist, found Mackintosh "steadfast and reliable", and believed that the Ross Sea party would have achieved much less, but for Mackintosh's unwearying drive. John King Davis, too, admired Mackintosh's dedication and called the depot-laying journey a "magnificent achievement". Shackleton was equivocal. In South he acknowledges that Mackintosh and his men achieved their object, praises the party's qualities of endurance and self-sacrifice, and asserts that Mackintosh died for his country. On the other hand, in a letter home he is highly critical: "Mackintosh seemed to have no idea of discipline or organisation ...". Shackleton did, however, donate part of the proceeds from a short New Zealand lecture tour to assist the Mackintosh family. His son, Lord Shackleton, in a much later assessment of the expedition, wrote: "Three men in particular emerge as heroes: Captain Aeneas Mackintosh, ... Dick Richards, and Ernest Joyce."

Mackintosh had two daughters, the second born while he was in Australia awaiting the Aurora's departure. On the return Barrier journey in February 1916, expecting to die, he wrote a poignant farewell message, with echoes of Captain Scott. The message concludes: "If it is God's will that we should have given up our lives then we do so in the British manner as our tradition holds us in honour bound to do. Goodbye, friends. I feel sure that my dear wife and children will not be neglected." In 1923 Gladys Mackintosh married Joseph Stenhouse, Auroras first officer and later captain.

Mackintosh, who had received a silver Polar Medal for his work during the Nimrod Expedition, is commemorated by Mt. Mackintosh

at 74°20′S 162°15′E.

Ross Sea Party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914–17. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar route established by earlier Antarctic expeditions...

as part of Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition , also known as the Endurance Expedition, is considered the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent...

, 1914–17. The Ross Sea party's mission was to support Shackleton's proposed transcontinental march by laying supply depots along the latter stages of the march's intended route. In the face of persistent setbacks and practical difficulties, Mackintosh's party fulfilled its task, although Mackintosh and two others died in the course of their duties.

Mackintosh's first Antarctic experience was as second officer

Second Mate

A second mate or second officer is a licensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. The second mate is the third in command and a watchkeeping officer, customarily the ship's navigator. Other duties vary, but the second mate is often the medical officer and in charge of maintaining...

on Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition

Nimrod Expedition

The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09, otherwise known as the Nimrod Expedition, was the first of three expeditions to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton. Its main target, among a range of geographical and scientific objectives, was to be first to the South Pole...

, 1907–09. Shortly after his arrival in the Antarctic a shipboard accident destroyed his right eye, and he was sent back to New Zealand. He returned in 1909 to participate in the later stages of the expedition; his will and determination in adversity impressed Shackleton, and led to his Ross Sea party appointment in 1914.

Mackintosh's operational orders were confused through communication failures, and he was uncertain of the timing of Shackleton's proposed march. His difficulties were compounded when the party's ship, SY Aurora, was swept from its winter moorings during a gale and was unable to return. Despite this loss of equipment, supplies and personnel, Mackintosh and his stranded shore party managed to carry out its depot-laying task to the full. Mackintosh himself barely survived the ordeal, owing his life to the actions of his comrades. He and one companion then attempted to cross the 13 nmi (24.1 km; 15 mi) of sea ice separating the party from its base, but the pair disappeared during a blizzard

Blizzard

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong winds. By definition, the difference between blizzard and a snowstorm is the strength of the wind. To be a blizzard, a snow storm must have winds in excess of with blowing or drifting snow which reduces visibility to 400 meters or ¼ mile or...

and are presumed to have fallen through the ice. Their bodies were never recovered.

Mackintosh's competence, and his shortcomings as a leader, have been questioned by commentators. Shackleton himself commended the work of Mackintosh and his comrades, and equated the sacrifice of their lives to those given in the trenches of the First World War. At the same time he was critical of Mackintosh's organising skills. Years later, Shackleton's son, Lord Shackleton, identified Mackintosh as one of the expedition's heroes, alongside Ernest Joyce

Ernest Joyce

Ernest Edward Mills Joyce AM was a Royal Naval seaman and explorer who participated in four Antarctic expeditions during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, early in the early 20th century. He served under both Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton...

and Dick Richards.

Early life

Mackintosh was born in TirhutTirhut

Historically Tirhut refers to the Indo-Gangetic plains lying north of the Ganges River, in the Indian state of Bihar. The geographical area known as Tirhut corresponds to the ancient region of Mithila. Tirhut, a densely populated area of India, has alluvial plains and several rivers pass through...

, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, on 1 July 1879, one of six children (five sons and a daughter) of Scottish indigo planter, Alexander Mackintosh, a descendent of the chieftains of Clan Chattan

Chattan Confederation

Clan Chattan or the Chattan Confederation is a confederation of 16 Scottish clans who joined for mutual defence or blood bonds. Its leader was the chief of Clan Mackintosh.-Origins:The origin of the name Chattan is disputed...

. Aeneas would in due course be named as an heir to the chieftainship, and to the ancient seat at Inverness

Inverness

Inverness is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for the Highland council area, and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands of Scotland...

that went with it. His privileged expatriate background and "cut-glass diction" led his friend and fellow Antarctic captain John King Davis

John King Davis

John King Davis, CBE was an English-born Australian explorer and navigator notable for his work captaining exploration ships in Antarctic waters as well as for establishing meteorological stations on Macquarie Island in the subantarctic and on Willis Island in the Coral Sea.-Early life:Davis's...

to describe him as a "sahib"

Sahib

Sahib is an Urdu term which literally translates to "Owner" or "Proprietor". The primary Arabic meaning of Sahib is "associate, companion, comrade, friend" though it also includes "Sahib is an Urdu term which literally translates to "Owner" or "Proprietor". The primary Arabic meaning of Sahib...

. When Mackintosh was still a young child his mother, Annie Mackintosh, suddenly returned to Britain, bringing the children with her, and the father thereafter disappears from the family story. At home in Bedfordshire, Mackintosh attended Bedford Modern School

Bedford Modern School

Bedford Modern School is a British co-educational independent school in the Harpur area of Bedford, in the county of Bedfordshire, in England.Bedford Modern comprises a junior school and a senior school...

. He then followed the same path as had Shackleton five years earlier, leaving school aged 16 to go to sea. After serving a tough Merchant Officer's apprenticeship he joined the P and O Line

Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company

The Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, which is usually known as P&O, is a British shipping and logistics company which dated from the early 19th century. Following its sale in March 2006 to Dubai Ports World for £3.9 billion, it became a subsidiary of DP World; however, the P&O...

, remaining with this company until recruited by Shackleton in 1907, as second officer on Nimrod, bound for Antarctica. He was commissioned Sub-Lieutenant

Sub-Lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is a military rank. It is normally a junior officer rank.In many navies, a sub-lieutenant is a naval commissioned or subordinate officer, ranking below a lieutenant. In the Royal Navy the rank of sub-lieutenant is equivalent to the rank of lieutenant in the British Army and of...

in the Royal Naval Reserve

Royal Naval Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve is the volunteer reserve force of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. The present Royal Naval Reserve was formed in 1958 by merging the original Royal Naval Reserve and the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve , a reserve of civilian volunteers founded in 1903...

in 1908.

Nimrod Expedition

Nimrod Expedition

The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09, otherwise known as the Nimrod Expedition, was the first of three expeditions to the Antarctic led by Ernest Shackleton. Its main target, among a range of geographical and scientific objectives, was to be first to the South Pole...

, 1907–1909, was the first of three Antarctic expeditions led by Ernest Shackleton. Its ambitious objective, as stated by Shackleton, was to "proceed to the Ross Quadrant of the Antarctic with a view to reaching the Geographical South Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

and the South Magnetic Pole

South Magnetic Pole

The Earth's South Magnetic Pole is the wandering point on the Earth's surface where the geomagnetic field lines are directed vertically upwards...

". It is possible that Shackleton approached the P & O line for suitable officers, and that Mackintosh was recommended to him. Mackintosh evidently jumped at the chance to join the expedition, and soon earned Shackleton's confidence while impressing his fellow-officers with his will and determination. While the expedition was in New Zealand Shackleton added Mackintosh to the shore party.

Accident

On 31 January 1908, not long after Nimrods arrival in the Antarctic, Mackintosh was assisting in the transfer of sledging gear aboard ship when a hook swung across the deck and struck his right eye, virtually destroying it. He was immediately taken to the captain's cabin where, later that day, expedition doctor Eric MarshallEric Marshall

Eric Marshall was an Antarctica explorer with the Nimrod Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton in 1907-09, and was one of the party of four who reached Furthest South at on 9 January 1909...

operated to remove the eye, using partly improvised surgical equipment. Marshall was deeply impressed by Mackintosh's fortitude, observing that "no man could have taken it better." The accident cost Mackintosh his place on the shore party, and required his return to New Zealand for further treatment. He took no part in the main events of the expedition, but returned south with Nimrod in January 1909, to participate in the closing stages. Shackleton, who had earlier fallen out with the ship's master, Rupert England, had wanted Mackintosh to captain Nimrod on this second voyage south, but the eye injury had not healed sufficiently to make this appointment possible.

Lost on the ice

On 1 January 1909 Nimrod, on its way south to relieve the expedition, was stopped by the ice, still 25 miles (40.2 km) from the expedition's shore base at Cape RoydsCape Royds

Cape Royds, Antarctica, is a dark rock cape forming the west extremity of Ross Island, facing on McMurdo Sound. Discovered by the Discovery Expedition and named for Lieutenant Charles W.R. Royds, Royal Navy, who acted as meteorologist for the expedition...

. Mackintosh decided that he would lead a party in a march across the ice, to carry the mails ashore. Historian Beau Riffenburgh

Beau Riffenburgh

Beau Riffenburgh is an author and historian specializing in polar exploration. He is also an award winning American Football coach and author of books on football history.- Early career :...

describes the journey that followed as "one of the most ill-considered parts of the entire expedition".

The party, which left the ship on the morning of 3 January, consisted of Mackintosh and three sailors, with a sledge containing supplies and a large postbag. Two sailors quickly returned to the ship, while Mackintosh and one companion went forward. They camped on the ice that evening, only to find next day that the whole area around them had broken up. After a desperate dash over the moving floes they managed to reach a small glacier

Glacier

A glacier is a large persistent body of ice that forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. At least 0.1 km² in area and 50 m thick, but often much larger, a glacier slowly deforms and flows due to stresses induced by its weight...

tongue, where they camped and waited for several days for their snow-blindness

Snow blindness

Photokeratitis or ultraviolet keratitis is a painful eye condition caused by exposure of insufficiently protected eyes to the ultraviolet rays from either natural or artificial sources. Photokeratitis is akin to a sunburn of the cornea and conjunctiva, and is not usually noticed until several...

to subside. When their vision returned, they found that Cape Royds was in sight but inaccessible, as the sea-ice leading to it had gone. After a further wait, they decided to make for the hut by land, a dangerous undertaking without appropriate equipment and experience.

On 11 January they set out. The next 48 hours involved a perpetual struggle over the hostile terrain, through regions of deep crevasses and treacherous snowfields. They soon parted company with all their equipment and supplies. At one point, in order to proceed, they had to ascend to 3000 feet (914.4 m) and then slide to the foot of a snow-slope. After another 24 hours of stumbling around in the fog, by chance they encountered Bernard Day, a member of the shore party, a short distance from the hut. The ship later recovered the abandoned postbag. John King Davis, then serving as Nimrod's chief officer, remarked that "Mackintosh was always the man to take the hundredth chance. This time he got away with it."

Mackintosh then joined Ernest Joyce and others on a journey across the Great Ice Barrier

Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica . It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than 600 km long, and between 15 and 50 metres high above the water surface...

to Minna Bluff

Minna Bluff

Minna Bluff is a rocky promontory at the eastern end of a volcanic Antarctic peninsula projecting deep into the Ross Ice Shelf at . It forms a long, narrow arm which culminates in a south-pointing hook feature , and is the subject of research into Antarctic cryosphere history, funded by the...

, to lay a depot for Shackleton's polar party, whose return from their southern march was awaited. On 3 March, while keeping watch on the deck of Nimrod, Mackintosh observed a flare which signaled the safe arrival of Shackleton.

Between expeditions

Mackintosh returned to England in June 1909. On reporting to the P & O, he was informed that due to his impaired sight he was discharged. Without immediate prospects of employment he agreed, early in 1910, to accompany Douglas MawsonDouglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson, OBE, FRS, FAA was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer and Academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton, Mawson was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.-Early work:He was appointed geologist to an...

(who had served as a geologist on the Nimrod Expedition and was later to lead the Australasian Antarctic Expedition

Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was an Australasian scientific team that explored part of Antarctica between 1911 and 1914. It was led by the Australian geologist Douglas Mawson, who was knighted for his achievements in leading the expedition. In 1910 he began to plan an expedition to chart...

) on a trip to Hungary, to survey a potential goldfield which Shackleton was hoping would form the basis of a lucrative business venture. Despite a promising report from Mawson nothing came of this. Mackintosh later launched his own treasure-hunting expedition to Cocos Island

Cocos Island

Cocos Island is an uninhabited island located off the shore of Costa Rica . It constitutes the 11th district of Puntarenas Canton of the province of Puntarenas. It is one of the National Parks of Costa Rica...

off the Panama

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

Pacific coast, but again returned home empty-handed.

In February 1912 Mackintosh married Gladys Campbell, and settled into an office job as assistant secretary to the Imperial Merchant Service Guild in Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

. The safe, routine work did not satisfy him: "I am still existing at this job, stuck in a dirty office," he wrote to a former Nimrod shipmate. "I always feel I never completed my first initiation—so would like to have one final wallow, for good or bad!"

Ross Sea party

Early difficulties

Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition envisioned two separate components. From a party based in the Weddell SeaWeddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast, Queen Maud Land. To the east of Cape Norvegia is...

a group of six led by Shackleton would march across the continent, via the South Pole. A separate Ross Sea party, based on the opposite side of the continent in McMurdo Sound

McMurdo Sound

The ice-clogged waters of Antarctica's McMurdo Sound extend about 55 km long and wide. The sound opens into the Ross Sea to the north. The Royal Society Range rises from sea level to 13,205 feet on the western shoreline. The nearby McMurdo Ice Shelf scribes McMurdo Sound's southern boundary...

, would lay supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier and would assist the transcontinental party on the final stages of its journey. Mackintosh was originally to be a member of the crossing party, but difficulties arose over the appointment of a commander for the Ross Sea party. Eric Marshall, the surgeon from the Nimrod expedition, turned the assignmemt down, as did John King Davis; Shackleton's efforts to obtain from the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

a naval crew for this part of the enterprise were rejected. Consequently the post of Ross Sea party leader was offered to Mackintosh. His ship would be the Aurora, lately used by Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition and presently lying in Australia. Shackleton considered the Ross Sea party's assignment routine, and saw no special difficulties in its execution.

Mackintosh arrived in Australia in October 1914 to take up his duties, and was immediately faced with major problems. Without warning, Shackleton had cut the Ross Sea party's allocated funds from £2,000 (current value £) to £1,000; Mackintosh was instructed to "get whatever you can free as gifts", and to mortgage the expedition's ship to raise further money. It then emerged that the purchase of Aurora had not been properly completed, which delayed Mackintosh's attempts to mortgage it. Worse, Aurora was quite unfit for Antarctic work without an extensive overhaul, which required co-operation from an exasperated Australian Government. The tasks of dealing with these difficulties within a very restricted timescale caused Mackintosh great anxiety, and the ensuing muddles together with public relations failures created among the Australian public "an unpleasant feeling with regard to the Expedition", according to the party's chief scientist Alexander Stevens. Some members of the party resigned, others were dismissed; recruiting a full complement of crew and scientific staff involved some last-minute appointments which left the party noticeably short of Antarctic experience.

Shackleton had given Mackintosh the impression that he would attempt his crossing during the coming 1914–15 Antarctic season, if possible. Before departing for the Weddell Sea Shackleton had evidently changed his mind about the feasibility of this. According to Daily Chronicle

Daily Chronicle

The Daily Chronicle was a British newspaper that was published from 1872 to 1930 when it merged with the Daily News to become the News Chronicle.-History:...

correspondent Ernest Perris, Mackintosh's instructions should have been corrected by cable, but this was never sent. The result of this misunderstanding was the chaotic depot-laying journeys of January–March 1915.

Depot-laying, first season

Aurora finally left HobartHobart

Hobart is the state capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Founded in 1804 as a penal colony,Hobart is Australia's second oldest capital city after Sydney. In 2009, the city had a greater area population of approximately 212,019. A resident of Hobart is known as...

, Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

, on 24 December 1914, and on 16 January 1915 had reached McMurdo Sound where Mackntosh established its base at Captain Scott's old headquarters at Cape Evans

Cape Evans

Cape Evans is a rocky cape on the west side of Ross Island, forming the north side of the entrance to Erebus Bay.The cape was discovered by the Discovery expedition under Robert Falcon Scott, who named it the Skuary. Scott's second expedition, the British Antarctic Expedition , built its...

. Believing that Shackleton might have already begun his march from the Weddell Sea, Mackintosh was determined that depots should be laid at 79° and 80°S, and that the work should begin at once. Ernest Joyce, the expedition's most seasoned Antarctic traveller—he had been with Scott's Discovery Expedition

Discovery Expedition

The British National Antarctic Expedition, 1901–04, generally known as the Discovery Expedition, was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic regions since James Clark Ross's voyage sixty years earlier...

in 1901–04, and with the Nimrod Expedition in 1907–09—protested that the party needed time for acclimatization and training, but was overruled. Joyce had expected that Mackintosh would defer to him on sledging matters: "If I had Shacks here I would make him see my way of arguing", he wrote in his diary. The depot-laying journey which followed began with a series of mishaps. A blizzard delayed their start, a motor sledge broke down after a few miles, and Mackintosh and his group lost their way on the sea ice between Cape Evans and Hut Point. Conditions on the Barrier were harsh for the untrained and inexperienced men. Many of the stores taken on to the Barrier were dumped on the ice to reduce loads and did not reach the depots. After Mackintosh insisted on taking the dogs the full distance to 80°S—over Joyce's urgent protests—all died on the return journey. The men, frostbitten and exhausted, reached Hut Point on 24 March, cut off from the ship and from their Cape Evans base by unsafe sea ice. After this experience confidence in Mackintosh's leadership was low, and bickering rife.

Loss of Aurora

Ernest Wild

Henry Ernest Wild AM , known as Ernest Wild, was a British Royal Naval seaman and Antarctic explorer, a younger brother of Frank Wild...

, was to the fore in improvising clothing, footwear and equipment from Scott's abandoned materials. However, these long winter months were difficult times for Mackintosh. Lacking the presence of a fellow-officer, he found it hard to form close relationships with his companions. His position became increasingly isolated, and subject to the increasingly vocal criticisms of Joyce in particular.

March to Mount Hope

On 1 September 1915 nine men in teams of three began the task of hauling approximately 5000 pounds (2,268 kg) of stores from the Cape Evans base on to the Barrier. This was the first stage in the process of laying down depots at one-degree latitude intervals down to Mount HopeMount Hope

There are several places named Mount Hope:in Antarctica*Mount Hope , a hill at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier*Mount Hope , a mountain in the Eternity Range, Palmer Landin Australia:* Mount Hope, New South Wales...

, at the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. A large forward base was then established at the Bluff depot, just north of 79°, from which the final journeys to Mount Hope would be launched early in 1916. During these early stages Mackintosh clashed repeatedly with Joyce over methods. In a showdown on 28 November, confronted with incontrovertible evidence of the greater effectiveness of Joyce's methods over his own, Mackintosh was forced to back down and accept a revised plan drafted by Joyce and Richards. Joyce's private comment was "I never in my experience came across such an idiot in charge of men."

Arnold Spencer-Smith

Arnold Patrick Spencer-Smith was a British clergyman and amateur photographer who joined Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–17, as Chaplain and photographer on the Ross Sea party. The hardship of the expedition resulted in Spencer-Smith's death...

were hobbling. Shortly after the 83° mark was passed, Spencer-Smith collapsed and was left in a tent while the others struggled on the remaining few miles. Mackintosh rejected the suggestion that he should remain with the invalid, insisting that it was his duty to ensure that every depot was laid. On 26 January Mount Hope was attained and the final depot put in place.

On the homeward march Spencer-Smith had to be drawn on the sledge. Mackintosh's condition was deteriorating rapidly; unable to pull, he staggered alongside, crippled by the growing effects of scurvy. As his condition worsened, Mackintosh was forced from time to time to join Spencer-Smith as a passenger on the sledge. Even the fitter members of the group were handicapped by frostbite, snow-blindness and, increasingly, scurvy, as the journey became a desperate struggle for survival. On 8 March Mackintosh volunteered to remain in the tent while the others tried to get Spencer-Smith to the relative safety of Hut Point. Spencer-Smith died the next day. Richards, Wild and Joyce struggled on to Hut Point with the now stricken Hayward, before returning to rescue Mackintosh. By 18 March all five survivors were recuperating at Hut Point, having completed what Shackleton's biographers Marjory and James Fisher as "one of the most remarkable, and apparently impossible, feats of endurance in the history of polar travel."

Disappearance and death

Assessment

Mackintosh's own expedition diaries, which cover the period up to 30 September 1915, have not been published; they are held by the Scott Polar Research InstituteScott Polar Research Institute

The Scott Polar Research Institute is a centre for research into the polar regions and glaciology worldwide. It is a sub-department of the Department of Geography in the University of Cambridge, located on Lensfield Road in the south of Cambridge ....

. The two main sources available to Ross Sea party historians are Joyce's diaries, published in 1929 as The South Polar Trail, and the account of Dick Richards: The Ross Sea Shore Party 1914–17. Mackintosh's reputation is not well-served by either, particularly Joyce's partisan record, described by one commentator as his "self-aggrandizing epic". Joyce is generally scathing about Mackintosh's leadership; Richards's account is much shorter and more straightforward, although decades later, when he was the only member of the expedition still alive (he died in 1985, aged 91), he spoke out, claiming that Mackintosh on the depot-laying march was "tremendously pathetic", had "lost his nerve completely", and that the fatal ice walk was "suicide".

The circumstances of Mackintosh's death have led commentators to emphasise his impetuousness and incompetence. This generally negative view of him was not, however, unanimous among his comrades. Alexander Stevens, who was the Ross Sea party's chief scientist, found Mackintosh "steadfast and reliable", and believed that the Ross Sea party would have achieved much less, but for Mackintosh's unwearying drive. John King Davis, too, admired Mackintosh's dedication and called the depot-laying journey a "magnificent achievement". Shackleton was equivocal. In South he acknowledges that Mackintosh and his men achieved their object, praises the party's qualities of endurance and self-sacrifice, and asserts that Mackintosh died for his country. On the other hand, in a letter home he is highly critical: "Mackintosh seemed to have no idea of discipline or organisation ...". Shackleton did, however, donate part of the proceeds from a short New Zealand lecture tour to assist the Mackintosh family. His son, Lord Shackleton, in a much later assessment of the expedition, wrote: "Three men in particular emerge as heroes: Captain Aeneas Mackintosh, ... Dick Richards, and Ernest Joyce."

Mackintosh had two daughters, the second born while he was in Australia awaiting the Aurora's departure. On the return Barrier journey in February 1916, expecting to die, he wrote a poignant farewell message, with echoes of Captain Scott. The message concludes: "If it is God's will that we should have given up our lives then we do so in the British manner as our tradition holds us in honour bound to do. Goodbye, friends. I feel sure that my dear wife and children will not be neglected." In 1923 Gladys Mackintosh married Joseph Stenhouse, Auroras first officer and later captain.

Mackintosh, who had received a silver Polar Medal for his work during the Nimrod Expedition, is commemorated by Mt. Mackintosh

Mount Mackintosh

Mount Mackintosh is an Antarctic mountain, at, and is the northernmost peak in the Prince Albert Mountains range, within the Transantarctic Mountains. The range was discovered in 1841 by James Clark Ross and was extensively explored during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration...

at 74°20′S 162°15′E.

External links

- Aeneas Mackintosh at Scott Polar Research Institute includes letter and sledging plan prepared by Mackintosh

- "SY Aurora - Ships of the Polar Explorers" at coolantarctica.com