about his experience with his father, Shlomo,(Translated to Chlomo, in German) in the Nazi German

concentration camps at Auschwitz

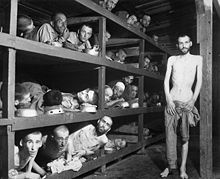

and Buchenwald

in 1944–1945, at the height of the Holocaust and toward the end of the Second World War. In just over 100 pages of sparse and fragmented narrative, Wiesel writes about the death of God and his own increasing disgust with humanity, reflected in the inversion of the father-child relationship as Shlomo declines to a helpless state and Wiesel becomes his resentful teenage caregiver. "If only I could get rid of this dead weight ... Immediately I felt ashamed of myself, ashamed forever." In Night, everything is inverted, every value destroyed. "Here there are no fathers, no brothers, no friends," a Kapo

tells him. "Everyone lives and dies for himself alone."

He was 16 years old when Buchenwald was liberated by the United States Army in April 1945, too late for his father, who died after a beating while Wiesel lay silently on the bunk below for fear of being beaten too. Having lost his faith in God and mankind, he vowed not to speak of his experience for ten years, to allow time, as he put it, to see clearly. In 1954 he wrote an 865-page manuscript in Yiddish, published as the 245-page Un di Velt Hot Geshvign ("And the World Remained Silent") in Buenos Aires in 1955, and in May that year the French novelist François Mauriac

persuaded him to write it for a wider audience.

Even with Mauriac's help, finding a publisher was not easy—they said it was too morbid, nobody wanted to hear these stories—but 178 pages appeared in 1958 in France as La Nuit, and in 1960 a 116-page version was published in the United States as Night. Fifty years later it had been translated into 30 languages, and ranked alongside Primo Levi

's If This Is a Man

and Anne Frank

's The Diary of a Young Girl

as one of the bedrocks of Holocaust literature. Unlike Levi's and Frank's work, it remains unclear how much of Wiesel's story is memoir. He has reacted angrily to the idea that any of it is fiction, calling it his deposition, but scholars have nevertheless had difficulty approaching it as an unvarnished account. Ruth Franklin writes that the ruthless pruning of the text from Yiddish to French transformed an angry historical account into a work of art.

Night is the first book in a trilogy—Night, Dawn, and Day—reflecting Wiesel's state of mind during and after the Holocaust. The titles mark his transition from darkness to light, according to the Jewish tradition of beginning a new day at nightfall. "In Night," he said, "I wanted to show the end, the finality of the event. Everything came to an end—man, history, literature, religion, God. There was nothing left. And yet we begin again with night."

Background

Wiesel was born on September 30, 1928 in Sighet

, a town in the Carpathian mountains

in northern Transylvania, annexed

by Hungary in 1940. With his father Shlomo, his mother Sarah, and his sisters—Hilda, Beatrice, and seven-year-old Tzipora—he lived in a close-knit community of between 10,000 and 20,000 mostly Orthodox Jews

. Night accurately reflects events in Hungary at the time. Ellen Fine writes that anti-Jewish legislation was enacted between 1938 and 1944, but the period Wiesel discusses at the beginning of the book, 1942 and 1943, was nevertheless a relatively calm one for the Jewish population.

That changed at midnight on March 18, 1944, with the invasion by Nazi Germany and the installation of Döme Sztójay

's puppet government. Adolf Eichmann

, commander of the Nazi's Sondereinsatzkommando (Special Action Unit), arrived in Hungary to oversee the deportation of its Jews to Auschwitz. Between May 15 and July 7, 1944, 450,000 Hungarian Jews were sent there, around 12,000 every day, most of them gassed.

As the Allies

prepared for the liberation of Europe

in May and June that year, Wiesel and his family were being deported to Auschwitz, along with 15,000 Jews from Sighet and 18,000 from neighboring villages. Wiesel's mother and Tzipora were immediately sent to the gas chamber. Hilda and Beatrice survived, separated from the rest of the family. Wiesel and his father managed to stay together, surviving hard labor and a death march

to another concentration camp, Buchenwald, where Wiesel watched his father die just weeks before the Sixth Armored Division of the U.S. Third Army arrived to liberate them.

Moshe the Beadle

Nights narrator is Eliezer, a pious Orthodox Jewish teenager, who studies the Talmudby day, and at night runs to the synagogue to weep over the destruction of the Temple

, part of his nightly religious tradition, but also a prediction, writes Fine, of the shadow about to be cast over Europe's Jews. To the disapproval of his father, Eliezer spends his time there discussing the Kabbalah

and the mysteries of the universe with Moshe the Beadle

, the synagogue's caretaker and the town's humblest resident, "awkward as a clown" but much loved. Moshe tells him that "man raises himself toward God by the questions he asks Him," a theme that Night repeatedly turns to.

Toward the end of 1942, the Hungarian government rules that Jews unable to prove their citizenship will be expelled, and Moshe is crammed onto a cattle train and taken to Poland. Somehow he manages to escape, miraculously saved by God, he believes, so that he might save the Jews of Sighet. He hurries back to the village to tell what he calls the story of his own death, running from one household to the next: "Jews, listen to me! It's all I ask of you. No money. No pity. Just listen to me!"

The cattle train crossed the border into Poland, he tells them, where it was taken over by the Gestapo

, the German secret police. The Jews were transferred to lorries and driven to a forest in Galicia, near Kolomaye, where they were forced to dig pits. When they had finished, each prisoner had to approach the hole, present his neck, and was shot. Babies were thrown into the air and used as targets by machine gunners. Moshe tells them about Malka, the young girl who took three days to die, and Tobias, the tailor who begged to be killed before his sons; and how he, Moshe, was shot in the leg and taken for dead. But the Jews of Sighet would not listen, making Moshe Night's first unheeded witness

.

And as for Moshe, he wept.

The Sighet ghettos

Over the next 18 months, restrictions on Jews gradually increase. No valuables are to be kept in Jewish homes. They are not allowed to visit restaurants, attend the synagogue, or leave home after six in the evening. They must wear the yellow star at all times. Eliezer's father makes light of it:The yellow star? Oh well, what of it? You don't die of it ...

(Poor Father! Of what then did you die?)

The SS

decide to transfer the Jews to one of two ghettos, jointly run like a small town, each with its own council or Judenrat

.

The barbed wire which fenced us in did not cause us any real fear. We even thought ourselves rather well off; we were entirely self-contained. A little Jewish republic ... We appointed a Jewish Council, a Jewish police, an office for social assistance, a labor committee, a hygiene department—a whole government machinery. Everyone marveled at it. We should no longer have before our eyes those hostile faces, those hate-laden stares. Our fear and anguish were at an end. We were living among Jews, among brothers ...

It was neither German nor Jew who ruled the ghetto—it was illusion.

In May 1944, the Judenrat is told the ghettos will be closed with immediate effect and the residents deported. They are not told their destination, only that they may each take a few personal belongings. The next day, Eliezer watches as the Hungarian police, wielding truncheons and rifle butts, round up his friends and neighbors, then march them through the streets. "It was from that moment that I began to hate them, and my hate is still the only link between us today."

And there was I, on the pavement, unable to make a move. Here came the Rabbi, his back bent, his face shaved ... His mere presence among the deportees added a touch of unreality to the scene. It was like a page torn from some story book ... One by one they passed in front of me, teachers, friends, others, all those I had been afraid of, all those I once could have laughed at, all those I had lived with over the years. They went by, fallen, dragging their packs, dragging their lives, deserting their homes, the years of their childhood, cringing like beaten dogs.

Auschwitz

Eliezer and his family are crammed into a closed cattle wagon with 80 others, with no light, little to eat or drink, barely able to breathe. On their third night in the wagon, one woman, Madame Schächter, repeatedly becomes hysterical, screaming that she can see flames, until she is beaten into silence by the others. She is Night's second unheeded witness, believed only as the train reaches Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the others see the chimneys for themselves.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

For a part of a second I glimpsed my mother and my sisters moving away to the right. Tzipora held Mother's hand. I saw them disappear into the distance; my mother was stroking my sister's fair hair ... and I did not know that in that place, at that moment, I was parting from my mother and Tzipora forever.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The remainder of Night describes Eliezer's desperate efforts not to be parted from his father, not even to lose sight of him; his grief and shame at witnessing his father's decline into helplessness; and as their relationship changes and the young man becomes the older man's caregiver, his resentment and guilt, because his father's existence threatens his own. The stronger Eliezer's need to survive, the weaker the bonds that tie him to other people. His loss of faith in human relationships is mirrored in his loss of faith in God.

During the first night, as he and his father wait in line to be thrown into a firepit, he watches a lorry draw up and deliver its load of children into the fire. While his father recites the Kaddish

, the Jewish prayer for the dead—Eliezer writes that in the long history of the Jews, he does not know whether people have ever recited the prayer for the dead for themselves—Eliezer considers throwing himself against the electric fence. Just at that moment, he and his father are ordered to go to their barracks instead. But Eliezer is already destroyed. "[T]he student of the Talmud, the child that I was, had been consumed in the flames. There remained only a shape that looked like me."

There follows a passage that Ellen Fine writes contains the main themes of Night—the death of God, children, innocence, and the défaite du moi, or dissolution of the self, a recurring theme in Holocaust literature:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me, for all eternity, of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.

With the loss of self goes Eliezer's sense of time: "I glanced at my father. How he had changed! ... So much had happened within such a few hours that I had lost all sense of time. When had we left our houses? And the ghetto? And the train? Was it only a week? One night—one single night?"

God is not lost to Eliezer entirely. During the hanging of a child, which the camp is forced to watch, he hears someone ask: Where is God? Where is he? Not heavy enough for the weight of his body to break his neck, the boy dies slowly and in agony. Wiesel files past him, sees his tongue still pink and his eyes clear, and weeps.

Behind me, I heard the same man asking:

And I heard a voice within me answer him: ... Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows.

Fine writes that this is the central event in Night, the religious sacrifice, Isaac bound to the altar, Jesus nailed to the cross, described by Alfred Kazin

as the literal death of God. Afterwards the inmates celebrate Rosh Hashanah

, the Jewish new year, but Eliezer cannot take part.

Blessed be God's name? Why, but why would I bless Him? Every fiber in me rebelled. Because He caused thousands of children to burn in His mass graves? Because He kept six crematoria working day and night, including Sabbath

ShabbatShabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

and the Holy DaysJewish holidayJewish holidays are days observed by Jews as holy or secular commemorations of important events in Jewish history. In Hebrew, Jewish holidays and festivals, depending on their nature, may be called yom tov or chag or ta'anit...

? Because in His great might, He had created Auschwitz, Birkenau, BunaMonowiceMonowitz , initially established as a subcamp of Nazi Germany's Auschwitz concentration camp, was one of the three main camps in the Auschwitz concentration camp system, with an additional 45 subcamps in the surrounding area...

, and so many other factories of death? How could I say to Him: Blessed be Thou, Almighty, Master of the UniverseBerakhahIn Judaism, a berakhah, bracha, brokhe is a blessing, usually recited at a specific moment during a ceremony or other activity. The function of a berakhah is to acknowledge God as the source of all blessing...

, who chose usJews as a chosen peopleIn Judaism, "chosenness" is the belief that the Jews are the Chosen People, chosen to be in a covenant with God. This idea is first found in the Torah and is elaborated on in later books of the Hebrew Bible...

among all nations to be tortured day and night, to watch as our fathers, our mothers, our brothers end up in the furnaces? ... But now, I no longer pleaded for anything. I was no longer able to lament. On the contrary, I felt very strong. I was the accuser, God the accused.

Death march

In or around August 1944, Eliezer and Shlomo are transferred from Birkenau to Auschwitz III, a work camp, their lives reduced to the avoidance of violence and the constant search for food. "Bread, soup—these were my whole life. I was a body. Perhaps less than that even: a starved stomach." Their only joy is when the Americans bomb the camp. In January 1945, with the Soviet army approaching, the Germans decide to flee, taking 60,000 inmates on a death march to concentration camps in Germany. Eliezer and Shlomo march to Gleiwitz

to be put on a freight train to Buchenwald, a camp near Weimar

, 350 miles (563 km) from Auschwitz.

Pitch darkness. Every now and then, an explosion in the night. They had orders to fire on any who could not keep up. Their fingers on the triggers, they did not deprive themselves of this pleasure. If one of us had stopped for a second, a sharp shot finished off another filthy son of a bitch.

Near me, men were collapsing in the dirty snow. Shots.

Resting in a shed after marching 50 miles (80.5 km), Rabbi Eliahou asks if anyone has seen his son. They had stuck together for three years, "always near each other, for suffering, for blows, for the ration of bread, for prayer," but the rabbi had lost sight of him in the crowd and is now scratching through the snow looking for his son's corpse. "I hadn't any strength left for running. And my son didn't notice. That's all I know." Wiesel doesn't tell the man that his son had indeed noticed his father limping, and had run faster, letting the distance between them grow.

And, in spite of myself, a prayer rose in my heart, to that God in whom I no longer believed. My God, Lord of the Universe, give me strength never to do what Rabbi Eliahou's son has done.

The inmates spend two days and nights in Gleiwitz locked inside cramped barracks without food, water, or heat, literally sleeping on top of one another, so that each morning the living wake with the dead underneath them. There is more marching to the train station and onto a cattle wagon with no roof, and no room to sit down until other inmates make space by throwing the dead onto the tracks. They travel for ten days and nights, with only the snow falling on them for water. Of the 100 Jews in Wiesel's wagon, 12 survive the journey.

I woke from my apathy just at the moment when two men came up to my father. I threw myself on top of his body. He was cold. I slapped him. I rubbed his hand, crying:

Father! Father! Wake up. They're trying to throw you out of the carriage ...

His body remained inert ...

I set to work to slap him as hard as I could. After a moment, my father's eyelids moved slightly over his glazed eyes. He was breathing weakly.

You see, I cried.

The two men moved away.

Buchenwald and liberation

An alert sounds, the camp lights go out, and Eliezer, exhausted, follows the crowd to the barracks, leaving his father behind. He wakes at dawn on a wooden bunk, remembering that he has a father, and goes in search of him. "But at that same moment this thought came into my mind. Don't let me find him! If only I could get rid of this dead weight, so that I could use all my strength to struggle for my own survival, and only worry about myself. Immediately I felt ashamed of myself, ashamed forever."

His father is in another block, sick with dysentery. The other men in his bunk, a Frenchman and a Pole, attack Shlomo because he can no longer go outside to relieve himself. Eliezer is unable to protect him. "Another wound to the heart, another hate, another reason for living lost." Begging for water one night from his bunk, where he has lain for a week, Shlomo is beaten on the head with a truncheon by an SS officer for making too much noise. Eliezer lies in the bunk above and does nothing for fear of being beaten too. He hears his father make a rattling noise—"Eliezer"—but lies still. In the morning, January 29, 1945, he finds another man in his father's place. The Kapos had come before dawn and taken Shlomo to the crematorium.

His last word was my name. A summons, to which I did not respond.

I did not weep, and it pained me that I could not weep. But I had no more tears. And, in the depths of my being, in the recesses of my weakened conscience, could I have searched for it, I might perhaps have found something like—free at last!

Shlomo missed his freedom by just a few weeks. The Soviets had liberated Auschwitz 11 days earlier, and the Americans were making their way towards Buchenwald. Eliezer is transferred to the children's block where he stays with 600 others, dreaming of soup. On April 5, 1945, the inmates are told the camp is to be liquidated and they are to be moved—another death march. On April 11, with 20,000 inmates still inside, a Jewish resistance movement attacks the remaining SS officers and takes control. At six o'clock that evening, the first American tank arrives at the gates, and behind it the Sixth Armored Division of the U.S. Third Army. Eliezer is free.

1954: Un di Velt Hot Geshvign

, attending lectures by Jean-Paul Sartre

and Martin Buber

. To supplement his $16-a week-stipend, he taught Hebrew

, and worked as a translator for the militant Yiddish weekly Zion in Kamf, which eased him into journalism. In 1948, at the age of 19, he was sent to Israel as a war correspondent by the French newspaper L'arche, and after the Sorbonne, he became chief foreign correspondent of the Tel Aviv newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth

.

For ten years, he kept his story to himself. In 1979, he wrote: "So heavy was my anguish that I made a vow: not to speak, not to touch upon the essential for at least ten years. ... Long enough to regain possession of my memory. It was in 1954 that he started to write, on board a ship to Brazil where he had an assignment to cover Christian missionary activity in Jewish communities. "I wrote feverishly, breathlessly, without rereading. I wrote to testify, to stop the dead from dying, to justify my own survival ... My vow of silence would soon be fulfilled; next year would mark the tenth anniversary of my liberation ... The pages piled up on my bed. I slept fitfully, never participating in the ship's activities, constantly pounding away on my little portable, oblivious of my fellow passengers ..."

By the end of the journey, Wiesel had an 862-page manuscript that he called Un di Velt Hot Geshvign ("And the World Remained Silent"). On the ship, he was introduced by friends to Mark Turkov, a publisher of Yiddish texts, and he gave Turkov the only copy of his manuscript. It was published that year in Buenos Aires by the Tzentral Varband fun Polishe Yidn in Argentina (Central Union of Polish Jews in Argentina) as a 245-page volume, the 117th book in a 176-volume series of Yiddish memoirs of Poland and the war, called Dos poylishe yidntum (Polish Jewry, Buenos Aires 1946–1966). Whereas the other books in the series were testimonials to the victims, Ruth Wisse writes that Un di Velt Hot Geshvign stood out as a "highly selective and isolating literary narrative" influenced by Wiesel's reading of the French existentialists

.

The book attracted no literary interest and Wiesel continued with his journalism. In May 1955, he wanted to interview the French prime minister, Pierre Mendes-France

, and approached the novelist François Mauriac, a friend of Mendes-France, for an introduction. He writes: "The problem was that [Mauriac] was in love with Jesus. He was the most decent person I ever met in that field— as a writer, as a Catholic writer. Honest, sense of integrity, and he was in love with Jesus. He spoke only of Jesus. Whatever I would ask—Jesus. Finally, I said, "What about Mendès-France?" He said that Mendès-France, like Jesus, was suffering..."

When he said Jesus again I couldn't take it, and for the only time in my life I was discourteous, which I regret to this day. I said, "Mr. Mauriac," we called him Maître, "ten years or so ago, I have seen children, hundreds of Jewish children, who suffered more than Jesus did on his cross and we do not speak about it." I felt all of a sudden so embarrassed. I closed my notebook and went to the elevator. He ran after me. He pulled me back; he sat down in his chair, and I in mine, and he began weeping. I have rarely seen an old man weep like that, and I felt like such an idiot ... And then, at the end, without saying anything, he simply said, "You know, maybe you should talk about it."

1960: Night

Wiesel translated Un di Velt Hot Geshvign, and sent Mauriac a French manuscript within a year. Even with Mauriac's connections, no publisher could be found. They said it was too morbid. But in 1958, Jerome Linden of Les Editions de Minuitagreed to release a 178-page French translation retitled La Nuit, dedicated to Shlomo, Sarah, and Tzipora, with a preface by Mauriac. Wiesel's New York agent, Georges Borchardt, encountered same difficulty finding an American publisher. According to Wiesel: "Some thought the book too slender (American readers seemed to prefer fatter volumes), others too depressing (American readers seemed to prefer optimistic books). Some felt that its subject was too little known, others that it was too well known."

In 1960, Arthur Wang of Hill & Wang—who Wiesel writes "believed in literature as others believe in God"—agreed to pay a $100 pro-forma advance, and published a 116-page English edition in the U.S. in September that year as Night, translated by Stella Rodway of McGibbon & Kee. Wiesel was working at the time as a United Nations correspondent for Israeli newspapers and the Jewish Daily Forward in New York. It took three years to sell the first print run of 3,000 copies. It sold 1,046 copies over the next 18 months, at $3 a copy, but it attracted interest from reviewers, leading to television interviews with Wiesel and meetings with literary figures like Saul Bellow

.

By 1997, it was selling 300,000 copies a year in the United States, and by 2011 had sold six million copies in that country, and was available in 30 languages. Sales increased in January 2006 when it was chosen for Oprah's Book Club

. It was republished with a new translation by Wiesel's wife, Marion, and a new preface by Wiesel, and by February 13 that year, it was no. 1 in The New York Times bestseller list for paperback non-fiction. The book club's edition, with over two million sales, became the club's third overall bestseller.

Memoir or novel

Ruth Franklin argues that the book's impact stems from its construction. Its language is plain, but "every sentence feels weighted and deliberate, every episode carefully chosen and delineated ... One has the sense of merciless experience mercilessly distilled to its essence ..." She writes that the power of the narrative has come at the cost of literal truth. The Yiddish version was an historical work, political and angry, blaming the Jewish concept of chosenness

as the source of the Jews' troubles. Wiesel wrote in the 1956 Yiddish version: "We believed in God, had faith in man, and lived with the illusion that in each one of us is a sacred spark from the fire of the shekinah, that each one carried in his eyes and in his soul the sign of God. This was the source—if not the cause—of all our misfortune." In preparation for publication in France, Wiesel and his publisher pruned without mercy. Franklin writes that it was a work of art that emerged, rather than a faithful narrative.

Naomi Seidman, professor of Jewish culture at the Graduate Theological Union, wrote a comparative analysis of the Yiddish and French texts for a 1996 article in Jewish Social Studies, concluding that Night transforms the Holocaust into a religious event, the abdication of God, with the witness both priest and prophet; Wiesel himself said that Auschwitz was as important as Mount Sinai

. Seidman argues that there was not one Holocaust survivor in Night, but two—a Yiddish and a French—a view that Holocaust deniers

have exploited to imply that Wiesel has not been truthful about some of the scenes. Seidman herself was accused of Holocaust revisionism. She told The Jewish Daily Forward that, in re-writing rather than simply translating Un di Velt Hot Geshvign, Wiesel had replaced an angry survivor who regards "testimony as a refutation of what the Nazis did to the Jews," with one "haunted by death, whose primary complaint is directed against God, not the world, [or] the Nazis."

Seidman supports her thesis that the Yiddish and French were written for different audiences by comparing parts of the text that survived the pruning. For example, in the Yiddish, Wiesel writes that, after liberation, some of the male camp survivors run off to "fargvaldikn daytshe shikses" ("rape German shiksa

s"), whereas in the French, they "coucher avec les filles" ("sleep with girls"). Seidman argues that the Yiddish version is for the Jewish readers, who want to hear about Jewish boys taking revenge by raping German non-Jews

. For the rest of the world—the largely Christian readership—the anger is removed, and they are just young men sleeping with girls. Seidman writes that Wiesel may have suppressed the desire for vengeance on the advice of Mauriac, a Roman Catholic.

When the original version was written

There is confusion regarding when the first version was written. Wiesel implied that it was after his May 1955 meeting with Mauriac that he began to write. In an interview in 1996, he said: "[Mauriac] took me to the elevator and embraced me. And that year, the tenth year, I began writing my narrative. After it was translated from Yiddish into French, I sent it to him ... That made me not publish, but write." But Naomi Seidman notes—as does Wiesel in All Rivers Run to the Sea—that Mark Turkov, Wiesel's publisher in Argentina, was given the Yiddish manuscript in 1954, one year before Wiesel's meeting with Mauriac.In Rivers, Wiesel writes that the first version of Night was written on a boat en route to Brazil in 1954, and that he handed the original 862-page manuscript to Turkov on the boat. Although Turkov said he would return the manuscript, Wiesel writes that he did not see it again, but later in Rivers, he explains that he "cut down the original manuscript from 862 pages to the 245 of the published Yiddish edition." Seidman writes that "[t]hese confusing and possibly contradictory reports on the various versions of Night have generated a chain of similarly confusing critical comments."

Truth and memory

Ruth Franklin writes that Night's "resuscitation" by Oprah Winfrey came at a difficult time for the genre of memoir, after a previous book-club author, James Frey, was found to have fabricated parts of his autobiography, A Million Little Pieces

. She argues that Winfrey's endorsement of Wiesel's work was a canny move, perhaps designed to restore the book club's credibility with a book regarded as beyond criticism. She writes that Night has a useful lesson to teach about the complexities of memoir and memory, and that the story of how it came to be written reveals how many factors come into play in creating a memoir

: "the obligation to remember and to testify, certainly, but also the artistic and even moral obligation to construct a credible persona and to craft a beautiful work ... truth in prose, it turns out, is not always the same thing as truth in life."

Wiesel tells a story about a visit to a Rebbe

, a Hasidic

rabbi, he hadn't seen for 20 years. The Rebbe is upset to learn that Wiesel has become a writer, and wants to know what he writes. "Stories," Wiesel tells him, "... true stories":

About people you knew? "Yes, about people I might have known." About things that happened? "Yes, about things that happened or could have happened." But they did not? "No, not all of them did. In fact, some were invented from almost the beginning to almost the end." The Rebbe leaned forward as if to measure me up and said with more sorrow than anger: That means you are writing lies! I did not answer immediately. The scolded child within me had nothing to say in his defense. Yet, I had to justify myself: "Things are not that simple, Rebbe. Some events do take place but are not true; others are—although they never occurred."

Further reading

- The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, accessed July 2, 2010.

- Cargas, Harry James (1992). In Conversation with Elie Wiesel. Diamond Communications. ISBN 0-912083-58-1

- Cargas, Harry James (ed.) (1993). Telling the Tale: A Tribute to Elie Wiesel. Time Being Books. ISBN 1-56809-007-2

- Greenberg, Irving, and Alvin H. Rosenfeld (eds.) (1978). Confronting the Holocaust: The Impact of Elie Wiesel. Indiana University Press.

- Sibelman, Simon P. (1995). Silence in the Novels of Elie Wiesel. St. Martin's Press.

- Wieseltier, Leon (1998). Kaddish. Random House.

- Young, James E. (1988). Writing and Rewriting the Holocaust. Indiana University Press.

Study guides

- "Night Book Notes", BookRags, accessed July 2, 2010.

- "Night Study Notes", Sparknotes, accessed July 2, 2010.

- "Night Study Guide & Essays", GradeSaver, accessed July 2, 2010.

- "Night , Novelguide.com, accessed July 2, 2010.