Meridian race riot of 1871

Encyclopedia

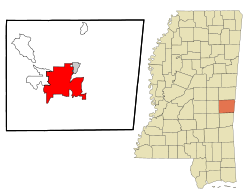

Meridian, Mississippi

Meridian is the county seat of Lauderdale County, Mississippi. It is the sixth largest city in the state and the principal city of the Meridian, Mississippi Micropolitan Statistical Area...

in March 1871. It followed the arrest of freedmen accused of inciting riot in a downtown fire, and blacks' organizing for self-defense. Although the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) had attacked freedmen since the end of the Civil War, generally without punishment, the first local arrest under the 1870 act to suppress the Klan was of a freedman, which angered the black community. During the trial of black leaders, the presiding judge was shot in the courtroom, and a gunfight erupted that killed several people. In the ensuing mob violence, whites killed as many as thirty blacks over the next few days. Whites drove the Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

mayor from office, and no one was tried in the freedmen's deaths.

The Meridian Riot was related to widespread postwar violence by whites to drive Reconstruction Republicans from office and restore white supremacy. Although the Enforcement Acts helped suppress the Klan at this time, the Meridian riot marked a turning point in Mississippi violence. By 1875 other white paramilitary

Paramilitary

A paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

groups arose; the Red Shirts suppressed black voting by intimidation, and their efforts led to a Democratic Party victory in state elections. Within two years a national political compromise was reached, and the federal government withdrew its military forces from the South.

Ku Klux Klan

After the American Civil WarAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

ended in 1865, the country underwent a period of Reconstruction. During this period, under the Reconstruction Acts the United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

directly controlled the states that were formerly part of the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. This takeover was resented by white Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

in the South, most of whom were temporarily disfranchised by service for the Confederacy. Their resentment increased with the passage of constitutional amendments making freedmen full citizens and the Voting Rights Act of 1867, which enabled freedmen to vote, serve on juries, and hold official positions in government.

The Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

(KKK) arose as independent chapters, part of the postwar insurgency related to the struggle for power in the South. In 1866, Mississippi Governor William L. Sharkey

William L. Sharkey

William Lewis Sharkey was an American judge and politician from Mississippi.-Biography:He was born in Sumner County, Tennessee, where he and his family lived until they moved to Warren County, Mississippi, when he was six years of age. In 1822, he was accepted into the bar at Natchez...

reported that disorder, lack of control and lawlessness were widespread. The Klan used public violence against blacks as intimidation. They burned houses, and attacked and killed blacks, leaving their bodies on the roads.

Meridian, the county seat of Lauderdale County, had a Republican mayor appointed by the governor. Sturgis was from Connecticut so opponents called him a carpetbagger

Carpetbagger

Carpetbaggers was a pejorative term Southerners gave to Northerners who moved to the South during the Reconstruction era, between 1865 and 1877....

. Southern Republicans were called scalawags. The KKK tried to intimidate a black school teacher named Daniel Price, who had migrated from Livingston, Alabama

Livingston, Alabama

Livingston is a city in Sumter County, Alabama, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 3,297. The city is the county seat of Sumter County.-Geography:Livingston is located at .According to the U.S...

, county seat of the Alabama county just to the east of Lauderdale. In Livingston, Price had been the leader of the local Loyal League, an organization established to help former slaves transition to freedom. Because of threats against him by local whites who opposed his activism, Price left the city for Mississippi and brought several freedmen with him. They hoped to find jobs in Meridian, a larger town. Numerous other African Americans had been migrating from Alabama to Mississippi since they had been freed and Alabama farmers were running short on labor. To try to force freedmen to return to Alabama and possibly stop the migration of others, Adam Kennard, deputy sheriff of Livingston (also described as a bounty hunter), was sent to arrest the men who went with Price to Meridian. He took some KKK men with him.

The Republican city officials refused to cooperate with Kennard and his group; they thought he was outside his legal jurisdiction

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is the practical authority granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice within a defined area of responsibility...

. Freedmen were angered by the Klan's presence, yet neither they nor the Republican city government had enough power to deter them. One night when Kennard was sleeping, Price and a band of about six freedmen in disguise took him from the house, carried him outside the city limits, and beat him. Kennard managed to get away and pressed charges against Price the next day. Price was prosecuted under a statute of the Civil Rights Act of 1866

Civil Rights Act of 1866

The Civil Rights Act of 1866, , enacted April 9, 1866, is a federal law in the United States that was mainly intended to protect the civil rights of African-Americans, in the wake of the American Civil War...

, intended to stop the KKK's widespread violence. It classified committing an act of violence in disguise as a federal crime (related to the KKK practice of wearing masks and costumes to hide individual identities).

Price's trial

In the week before Price's trial, whites in Meridian began to threaten him. Freedmen were outraged that he had been arrested at all, as no one had been arrested or convicted for the many previous attacks on black people. Price was the first to be arrested under what was considered the federal anti-KKK law. Freedmen were angered that the law intended to protect them was being used against them. Before his trial, Price stated that he would not pay his bond and would not go to jail. He claimed that if he were convicted, his supporters "would begin shooting." When an armed party of about 50 white men came from Livingston to witness the trial, city officials became uneasy. They postponed the trial for a week. During the Alabamans' visit to Meridian, the men arrested several freedmen who had migrated with Price to the city. They claimed the men had forfeited labor contracts and, in some cases, stolen money.At the second date for Price's trial, one of the state witnesses for Kennard was ill, so the court postponed the trial for another week. During this time, several prominent city employees told Mayor Sturgis of their concern that if Price were tried, there was a risk of mass unrest. They suggested avoiding the trial but forcing Price to leave the city. Sturgis and other officials made a deal with the prosecutors, and they freed Price on the condition that he leave the city.

Given Price's absence at his third trial date, the prosecutor dropped the charges against him, but the black community of Meridian was still furious. They learned that Kennard had arrested several Alabama freedmen and forced them to return to Livingston. The white community organized against Mayor Sturgis and petitioned to have him removed from office. Blacks countered with their own petition, which was sent to the Republican governor Adelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames

Adelbert Ames was an American sailor, soldier, and politician. He served with distinction as a Union Army general during the American Civil War. As a Radical Republican and a Carpetbagger, he was military governor, Senator and civilian governor in Reconstruction-era Mississippi...

, who had appointed Sturgis. Sturgis was not removed; opposed by prominent whites, he became increasingly worried about the hostility between the races.

Courthouse meeting

Shortly after Price's scheduled trial and departure, the 1870 gubernatorial election was held. The Republican James L. AlcornJames L. Alcorn

James Lusk Alcorn was a prominent American political figure in Mississippi during the 19th century. He was a leading southern white Republican or "scalawag" during Reconstruction in Mississippi, where he served as governor and U.S. Senator...

won, carrying Lauderdale County by a large majority on the basis of voting by freedmen. Given the unrest in Meridian, Mayor Sturgis requested federal troops, since no local officials were willing to prosecute the Alabamans or other whites in the city. The troops arrived, but stayed only a few days. With no major violence, they were withdrawn as the state's resources were limited. Sturgis began his own legal proceedings against some of the whites in the city, leading to greater opposition and renewed effort to have him removed. Sturgis sent several black advisers to the governor's office in Jackson

Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson is the capital and the most populous city of the US state of Mississippi. It is one of two county seats of Hinds County ,. The population of the city declined from 184,256 at the 2000 census to 173,514 at the 2010 census...

to plead his case.

When Sturgis's advisers returned to the city on Friday, March 3, 1871, they brought Aaron Moore, a Republican member of the Mississippi Legislature

Mississippi Legislature

The Mississippi Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Mississippi. The bicameral Legislature is composed of the lower Mississippi House of Representatives, with 122 members, and the upper Mississippi Senate, with 52 members. Both Representatives and Senators serve four-year...

from Lauderdale County. He called for a meeting the next day, March 4, at the county courthouse to make the case for keeping Sturgis in office. About 200 people showed up for the meeting but they included only a few whites. Speeches reportedly criticized militant whites and encouraged freedmen in self defense. The meeting adjourned at sundown, after which several of the black people in the meeting organized a military company

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

with William Clopton, one of Sturgis's advisers, leading the way. Some were armed with swords while others carried guns; many freedmen avoided the demonstration.

Downtown fire

Even before the meeting at the courthouse, trouble was brewing. Whites shared rumors of seeing crowds of armed African Americans traveling to the city, which raised their fears. A local store owner overheard a conversation predicting that crowds of people – both black and white – would be out on the streets that night. When the whites heard about the courthouse meeting, they decided that Sturgis, Clopton, and Warren Tyler, another of Sturgis's advisors and a speechmaker, should be forced to leave the city. They organized an armed search team to find them.About an hour after the meeting adjourned, a fire broke out in the business section of the city. The fire started on the second floor of a store owned by Theodore Sturgis, the mayor's brother. Although the cause of the fire is unknown, many people at the time thought the mayor was behind it. The fire was eventually put out, but not before two-thirds of the business district had been engulfed. The block had recently been rebuilt after being destroyed during General William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War , for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched...

's 1864 raid.

As the fire burned, Clopton was hit in the head with a shotgun barrel. Some witnesses thought he was killed but he was only wounded. Hearing of the attack, freedmen became enraged and began passing out guns. At the same time, groups of whites patrolled the streets as militias for the rest of the night. Over the next few days under mob rule, the sheriff arrested Clopton, Tyler and Moore, and charged them with inciting riot. Whites appointed a committee to remove Mayor Sturgis from office.

Rumors spread as wildly as the fire had; whites said the blacks would burn the entire city down. The sheriff told Moore at his church on Sunday that all black people in the city would be required to disarm. On Monday the committee started an investigation of the fire and concluded that Mayor Sturgis had set it.

The riot

After being arrested, Clopton, Tyler, and Moore were brought to trial on Monday, March 6. That morning, the whites held a meeting of their own and passed a resolution condemning the violent acts of Daniel Price, and those of Mayor Sturgis and other people – blacks and whites alike – on Saturday night, the night of the downtown fire. When William Tyler was arrested, Sheriff Moseley checked him for any firearms, of which he had none, and then allowed him to go to the barbershop for a haircut. The barber Jack Williams later claimed he had seen Tyler wearing a pistol on his side. Tyler went to the courtroom after leaving the barbershop.Judge E. L. Bramlette was presiding over the trial. Numerous Republicans and as many as two hundred Democrats were present in the courtroom. In general, the white people in the room were situated toward the front, and the black people were in the back. Before the examination of witnesses began, Mayor Sturgis was seen conversing with Tyler and handed him a written note. After the trial began, Tyler and Moore were taken into another room, and some reports say that Sturgis went in with them. Sturgis never returned to the courtroom, but when Tyler and Moore returned, several witnesses reported that Tyler had a pistol on his side they had not seen before.

The second witness to testify was James Brantley. Tyler asked Brantley to stay on the stand and reportedly said, "I want to introduce two or three witnesses to impeach your veracity." Outraged, Brantley took a cane of Marshal William S. Patton and lunged toward Tyler. Patton grabbed Brantley and told him to stop, and Tyler moved toward the courtroom door. Some witnesses claimed to have seen Tyler reach into his pocket for a gun. At this moment, the first shot was fired, although the person responsible is debated. Marshal Patton said he did not see Tyler shoot, but he thought the shot came from that direction. When the first shot was fired, Tyler was in little to no danger as he was 10 feet (3 m) to 12 feet (3.7 m) from Brantley. Several of the people in the courtroom at the time claimed that Tyler fired first.

Firearms were quickly drawn across the courtroom, and general shooting broke out. The shootout lasted somewhere between one and five minutes, and in the process, Judge Bramlette was killed, and Clopton was injured. Tyler sprinted to a second-floor veranda, hopped the railing, and jumped to the ground. The barber Jack Williams reported seeing him throw away what looked like a pistol as he jumped. Tyler limped towards Williams asking him for help, and then ran through the barber shop with several whites in pursuit. Dr. L. D. Belk, acting deputy sheriff, chased Tyler and asked men to gather arms and help in the pursuit. Tyler was found wounded in a ditch between the courthouse and Sam Parker's shop by a black laborer Joe Sharp. Sharp and two other men helped Tyler get to a store two doors down from Parker's shop. A white party later found Tyler and shot him many times, but there were so many in the crowd, that no one knew who had hit him.

After the courtroom shootout, Clopton was badly injured and placed under the protection of guards. Reportedly the two men grew tired and threw Clopton from the second story window, saying they "could not waste their time on a wounded Negro murderer." Clopton was carried back into the courthouse, where sometime during the night he died after his throat was cut.

Moore had fallen by Judge Bramlette and pretended to be dead. After the courthouse was cleared, he ran to the woods to follow the railroad line to Jackson. A mob chased him for 40 miles (64.4 km) or 50 miles (80.5 km), but they never caught up. He eventually made it to Jackson without harm, and was never arrested or brought to trial again. The white mob burned down Moore's house along with a Baptist church nearby, which had been donated by the United States government to serve as a school for blacks. Daniel Price had been a teacher there.

In the chaos after the courtroom shootout, whites killed many other blacks. When they could not find Tyler and Moore, they attacked other freedmen they came across. For three days, local Klansmen murdered "all the leading colored men of the town with one or two exceptions." Several black people were killed in the courtroom, and others died in the fires at Moore's house and the Baptist church. During the night of the shootings, three other blacks were arrested and taken to the courthouse. The next morning, they were found dead. By the time federal troops arrived several days later, about thirty black people had been killed. Many of the fatalities from the riot were buried in McLemore Cemetery

McLemore Cemetery

McLemore Cemetery is a cemetery in Meridian, Mississippi. The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 18, 1979, and is the oldest surviving historic site in the city.-History:...

.

Aftermath

During the riot, Mayor Sturgis hid in the atticAttic

An attic is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building . Attic is generally the American/Canadian reference to it...

of a boarding house

Boarding house

A boarding house, is a house in which lodgers rent one or more rooms for one or more nights, and sometimes for extended periods of weeks, months and years. The common parts of the house are maintained, and some services, such as laundry and cleaning, may be supplied. They normally provide "bed...

(owned by his brother Theodore.) He did not emerge until reaching agreement that he could resign and leave town. The day after the riot, men approached and ordered him to return to the North. He agreed to leave that night on a northbound train at midnight; he was escorted safely to the train by a group of about 300 white men. Upon reaching New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, he wrote an account of the events in a letter to the New York Daily Tribune:

The letter was reprinted widely in the North, and fueled the debate over toughening the restrictions in the Ku Klux Klan Law under considertion. News of the riot angered the Radical Republicans in Congress, and hastened the passage of the law, known as the Enforcement Act. Mississippi Democrats attacked the Radical Republicans for using the riot as a partisan point.

Gradually the situation in Meridian quieted down, but debate continued there and in Washington

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

. On March 21, the state began an investigation of the riot, calling a total of 116 witnesses. The state indicted six men under charges of unlawful assembly and assault with intent to kill. Many black witnesses had credible information as to who shot whom, but most were too afraid to testify, as they feared losing their jobs, rights, or their lives. None of the men responsible for the riot was charged or brought to trial. Two months later, a Congressional investigation re-examined the case but failed to identify the first shooter in the courthouse. The only person convicted of actions related to the riot was an Alabama KKK man charged with raping a black woman.

Effects

The Meridian riot highlighted the fact that blacks in the South were poorly armed, economically dependent on whites for jobs, and new to freedom; they had difficulty resisting violent attacks without federal help. By the mid 1870s, as war memories faded, Northern whites became tired of supporting the expensive programs to try to suppress the violence in the South and more inclined to let the states handle their own problems. Most Northerners viewed slavery as a moral wrong but did not necessarily believe in racial equality. They were discouraged by the continuing insurgency in much of the South. Whites resorted to force to suppress the opposition. With waning federal help, blacks had difficulty resisting white violence. The riot marked the decline of Republican power and the waning of Reconstruction in this part of Mississippi.By 1875 in Mississippi, paramilitary insurgent

Insurgent

Insurgent, insurgents or insurgency can refer to:* The act of insurgency-Specific insurgencies:* Iraqi insurgency, uprising in Iraq* Insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, uprising in India* Insurgency in North-East India...

groups, such as the Red Shirts and rifle leagues, described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party" had arisen in the Klan's place. They worked openly to intimidate Republican voters, especially freedmen, and run officials out of office. The insurgents suppressed voting to achieve Democratic landslide victories in the 1875 state elections. By the late 1870s, the Democrats had completed their takeover in Mississippi and other former Confederate states.

With control reestablished at the state government level, conservative Democrats passed electoral laws and constitutional amendments to restrict voting by freedmen and poor whites, resulting in their disfranchisement for decades. Mississippi was the first to pass such an amendment in 1890. Its surviving a United States Supreme Court review encouraged other Southern states to pass similar amendments, known as the "Mississippi Plan". State legislatures also passed Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

, which established racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

in public facilities. The next few decades after the Meridian Riot saw a rise in lynching

Lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial execution carried out by a mob, often by hanging, but also by burning at the stake or shooting, in order to punish an alleged transgressor, or to intimidate, control, or otherwise manipulate a population of people. It is related to other means of social control that...

s and violence against blacks across the South, which accompanied their loss of civil rights and the fight for white supremacy. Mississippi would lead the region in racial violence and public support of it. While the rate of lynchings declined into the 20th century, blacks had little legal standing for recourse against abuses until their successes of the African-American Civil Rights Movement and enforcement of their right to vote.

Further reading

- Hewitt Clarke, Thunder at Meridian, Lone Star Press, 1995

- Laura Nan Fairley and James T. Dawon, Paths to the Past: An Overview History of Lauderdale County, Mississippi, Lauderdale County Department of Archives and History, Inc., 1988

External links

- "Jim Crow History", Official Website.

- United States. Congress Joint Select Committee on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Government Printing Office, 1872 (Includes transcript of testimony in the investigation of the Meridian Race Riot of 1871 and state investigation)