Lord Alfred Douglas

Encyclopedia

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (22 October 187020 March 1945), nicknamed Bosie, was a British

author

, poet

and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde

. Much of his early poetry was Uranian

in theme, though he tended, later in life, to distance himself from both Wilde's influence and his own role as a Uranian poet

.

The third son of John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

The third son of John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

and his first wife, the former Sibyl Montgomery, Douglas was born at Ham Hill House in Worcestershire

. He was his mother's favourite child; she called him Bosie (a derivative of Boysie), a nickname

which stuck for the rest of his life.

Douglas was educated at Winchester College

(1884–88) and at Magdalen College, Oxford

(1889–93), which he left without obtaining a degree. At Oxford, Douglas edited an undergraduate journal The Spirit Lamp (1892-3), an activity that intensified the constant conflict between him and his father. Their relationship had always been a strained one and during the Queensberry-Wilde feud, Douglas sided with Wilde, even encouraging him to prosecute his own father for libel. In 1893, Douglas had a brief affair with George Ives

.

In 1860, Douglas's grandfather, the 8th Marquess of Queensberry

, had died in what was reported as a shooting accident, but his death was widely believed to have been suicide. In 1862, his widowed grandmother, Lady Queensberry, converted to Roman Catholicism and took her children to live in Paris

.

Apart from the violent death of his grandfather, there were other tragedies in Douglas's family. One of his uncles, Lord James Douglas, was deeply attached to his twin sister 'Florrie

' and was heartbroken when she married. In 1885, he tried to abduct a young girl, and after that became ever more manic. In 1888, Lord James married, but this proved disastrous. Separated from Florrie, James drank himself into a deep depression, and in 1891 committed suicide

by cutting his throat. Another of his uncles, Lord Francis Douglas

(1847–1865) had died in a climbing accident on the Matterhorn

, while his uncle Lord Archibald Edward Douglas (1850–1938) became a clergyman. (Alfred Douglas's only child was in turn to go mad, and died in a mental hospital.)

Alfred Douglas's aunt, Lord James's twin Lady Florence Douglas

(1855–1905), was an author, war correspondent

for the Morning Post

during the First Boer War

, and a feminist

. In 1890, she published a novel, Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900, in which women's suffrage

is achieved after a woman posing as a man named Hector l'Estrange is elected to the House of Commons

. The character l'Estrange is clearly based on Oscar Wilde

.

In 1891, Douglas met Oscar Wilde

In 1891, Douglas met Oscar Wilde

; although the playwright was married with two sons, they soon began an affair. In 1894, the Robert Hichens novel The Green Carnation

was published. Said to be a roman a clef

based on the relationship of Wilde and Douglas, it would be one of the texts used against Wilde during his trials in 1895.

Douglas, known to his friends as 'Bosie', has been described as spoiled, reckless, insolent and extravagant. He would spend money on boys and gambling and expected Wilde to contribute to his tastes. They often argued and broke up, but would also always reconcile.

Douglas had praised Wilde's play Salome

in the Oxford magazine, The Spirit Lamp, of which he was editor (and used as a covert means of gaining acceptance for homosexuality). Wilde had originally written Salomé in French, and in 1893 he commissioned Douglas to translate it into English. Douglas's French was very poor and his translation was highly criticised: a passage that goes "On ne doit regarder que dans les miroirs" (French for "One should only look in mirrors") was translated as "One must not look at mirrors". Douglas's temper would not accept Wilde's criticism and he claimed that the errors were really in Wilde's original play. This led to a hiatus in the relationship and a row between the two men, with angry messages being exchanged and even the involvement of the publisher John Lane

and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley

when they themselves objected to Douglas's work. Beardsley complained to Robbie Ross: "For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous". Wilde redid much of the translation himself, but, in a gesture of reconciliation, suggested that Douglas be dedicated as the translator rather than them sharing their names on the title-page. Accepting this, Douglas, in his vanity, compared a dedication to sharing the title-page as "the difference between a tribute of admiration from an artist and a receipt from a tradesman."

On another occasion, while staying together in Brighton

, Douglas fell ill with influenza

and was nursed back to health by Wilde, but failed to return the favour when Wilde fell ill as well. Instead Douglas moved to the Grand Hotel and, on Wilde's 40th birthday, sent him a letter saying that he had charged him the bill. Douglas also gave his old clothes to male prostitutes, but failed to remove incriminating letters exchanged between him and Wilde, which were then used for blackmail

.

Alfred's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, quickly suspected the liaison to be more than a friendship. He sent his son a letter, attacking him for leaving Oxford without a degree and failing to take up a proper career, such as a civil servant or lawyer. He threatened to "disown [Alfred] and stop all money supplies". Alfred responded with a telegram stating: "What a funny little man you are".

Queensberry was infuriated by this attitude. In his next letter he threatened his son with a "thrashing" and accused him of being "crazy". He also threatened to "make a public scandal in a way you little dream of" if he continued his relationship with Wilde.

Queensberry was well-known for his temper and threatening to beat people with a horsewhip. Alfred sent his father a postcard stating "I detest you" and making it clear that he would take Wilde's side in a fight between him and the Marquess, "with a loaded revolver".

In answer Queensberry wrote to Alfred (whom he addressed as "You miserable creature") that he had divorced Alfred's mother in order not to "run the risk of bringing more creatures into the world like yourself" and that, when Alfred was a baby, "I cried over you the bitterest tears a man ever shed, that I had brought such a creature into the world, and unwittingly committed such a crime... You must be demented".

When Douglas' eldest brother, Lord Drumlanrig

, heir to the marquessate of Queensberry, died in a suspicious hunting accident in October 1894, rumours circulated that Drumlanrig had been having a homosexual relationship with the Prime Minister

, Lord Rosebery

. The elder Queensberry thus embarked on a campaign to save his other son, and began a public persecution of Wilde. He and a minder confronted the playwright in his own home; later, Queensberry planned to throw rotten vegetables at Wilde during the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest

, but, forewarned of this, the playwright was able to deny him access to the theatre.

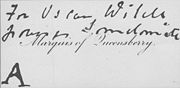

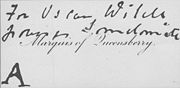

Queensberry then publicly insulted Wilde by leaving, at the latter's club, a visiting card

Queensberry then publicly insulted Wilde by leaving, at the latter's club, a visiting card

on which he had written: "For Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite"–a misspelling of "sodomite." The wording is in dispute – the handwriting is unclear – although Hyde reports it as this. According to Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, it is more likely "Posing somdomite," while Queensberry himself claimed it to be "Posing as somdomite." Holland suggests that this wording ("posing [as] ...") would have been easier to defend in court.

, Frank Harris

, and George Bernard Shaw

, Wilde had Queensberry arrested and charged with criminal libel in a private prosecution

, as sodomy

was then a crime. Several highly suggestive erotic letters that Wilde had written to Douglas were introduced into evidence; he claimed that they were works of art. Wilde was closely questioned about the homoerotic themes in The Picture of Dorian Gray

and in The Chameleon, a single-issue magazine published by Douglas to which he had contributed a short article. Queensberry's lawyer portrayed Wilde as a vicious older man who habitually preyed upon naive young boys and seduced them into a life of homosexuality with extravagant gifts and promises of a glamorous lifestyle.

Queensberry's attorney announced in court that he had located several male prostitutes who were to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. Wilde then dropped the libel charge, on his lawyers' advice, as a conviction was very unlikely if the libel were demonstrated in court to be true. Based on the evidence raised during the case, Wilde was arrested the next day and charged with committing sodomy

and "gross indecency

", a vague charge which covered all homosexual acts other than sodomy.

Douglas's 1892 poem Two Loves, which was used against Wilde at the latter's trial, ends with the famous line that refers to homosexuality

as the love that dare not speak its name

. Wilde gave an eloquent but counterproductive explanation of the nature of this love on the witness stand. The trial resulted in a hung jury

.

In 1895, when during his trials Wilde was released on bail

, Douglas's cousin Sholto Johnstone Douglas

stood surety

for £

500 of the bail money.

The prosecutor opted to retry the case. Wilde was convicted on 25 May 1895 and sentenced to two years' hard labour, first at Pentonville

, then Wandsworth

, then famously in Reading Gaol. Douglas was forced into exile in Europe.

While in prison, Wilde wrote Douglas a very long and critical letter entitled De Profundis

, describing exactly what he felt about him, which Wilde was not permitted to send, but which may or may not have been sent to Douglas after Wilde's release.

Following Wilde's release (19 May 1897), the two reunited in August at Rouen

, but stayed together only a few months owing to personal differences and the various pressures on them.

, but for financial and other reasons, they separated. Wilde lived the remainder of his life primarily in Paris

, and Douglas returned to England

in late 1898.

The period when the two men lived in Naples would later become quite controversial. Wilde claimed that Douglas had offered a home, but had no funds or ideas. When Douglas eventually did gain funds from his late father's estate, he refused to grant Wilde a permanent allowance, although he did give him occasional handouts. When Wilde died in 1900, he was relatively impoverished. Douglas served as chief mourner, although there reportedly was an altercation at the gravesite between him and Robert Ross

. This struggle would preview the later litigations between the two former lovers of Oscar Wilde.

, an heiress and poet. They married on 4 March 1902 and had one son, Raymond Wilfred Sholto Douglas (17 November 1902 - 10 October 1964) who was diagnosed with a schizo-affective disorder at the age of 24, and died unmarried, in a mental hospital.

against Noel Pemberton Billing

in 1918. Billing had accused Allan, who was performing Wilde's play Salome

, of being part of a homosexual conspiracy to undermine the war effort. Douglas also contributed to Billing's journal Vigilante as part of his campaign against Robert Ross. He had written a poem referring to Margot Asquith "bound with Lesbian fillets" while her husband Herbert

, the Prime Minister, gave money to Ross. During the trial he described Wilde as "the greatest force for evil that has appeared in Europe during the last three hundred and fifty years". Douglas added that he intensely regretted having met Wilde, and having helped him with the translation of Salome which he described as "a most pernicious and abominable piece of work".

and Cambridge for defamatory references to him in an article on Wilde.

He was a plaintiff and defendant in several trials for civil or criminal libel

. In 1913 he accused Arthur Ransome

of libelling him in his book Oscar Wilde: A Critical Study. He saw this trial as a weapon against his enemy Ross, not understanding that Ross would not be called to give evidence. In a similar way he had not appreciated the fact that his father's character would not be an issue when he urged Wilde to sue back in 1895. The court found in Ransome's favour. Ransome did remove the offending passages from the 2nd edition of his book.

In the most noted case, brought by Winston Churchill

in 1923, Douglas was found guilty of libelling Churchill and was sentenced to six months in prison. Douglas had claimed that Churchill had been part of a Jewish conspiracy to kill Lord Kitchener, the British

Secretary of State for War

. Kitchener had died on 5 June 1916, while on a diplomatic mission to Russia

: the ship in which he was travelling, the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire

, struck a German naval mine

and sank west of the Orkney Islands

. In spite of this libel claim, Douglas wrote a sonnet

in praise of Churchill in 1941.

In 1924, while in prison, Douglas, in an ironic echo of Wilde's composition of De Profundis (Latin

for "From the Depths") during his incarceration, wrote his last major poetic work, In Excelsis (literally, "In the highest"), which contains 17 canto

s. Since the prison authorities would not allow Douglas to take the manuscript with him when he was released, he had to rewrite the entire work from memory.

Douglas maintained that his health never recovered from his harsh prison ordeal, which included sleeping on a plank bed without a mattress.

Following his own incarceration in prison in 1924, Douglas's feelings toward Oscar Wilde began to soften considerably. He said in Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up that “Sometimes a sin is also a crime (for example, a murder or theft) but this is not the case with homosexuality, any more than with adultery”.

Throughout the 1930s and until his death, Douglas maintained correspondences with many people, including Marie Stopes

and George Bernard Shaw

. Anthony Wynn

wrote the play Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship based on the letters between Shaw and Douglas. One of Douglas's final public appearances was his well-received lecture to the Royal Society of Literature

on 2 September 1943, entitled The Principles of Poetry, which was published in an edition of 1,000 copies. He attacked the poetry of T. S. Eliot

, and the talk was praised by Arthur Quiller-Couch

and Augustus John

.

Douglas's only child, Raymond, was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder

in 1927 and entered St Andrew's Hospital

, a mental institution. He was decertified and released after five years, but suffered a subsequent breakdown and returned to the hospital. When his mother, Olive Douglas, died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 67, Raymond was able to attend her funeral and in June he was again decertified and released. However, his conduct rapidly deteriorated and he returned to St Andrew's in November where he stayed until his death on 10 October 1964.

at Lancing

in West Sussex on 20 March 1945 at the age of 74. He was buried on 23 March at the Franciscan Monastery

, Crawley

, West Sussex, where he is interred alongside his mother, Sibyl, Marchioness of Queensberry, who died on 31 October 1935 at the age of 91. A single gravestone covers them both. The elderly Douglas, living in reduced circumstances in Hove

in the 1940s, is mentioned in the Diaries of Chips Channon and the first autobiography of Sir Donald Sinden, both of whom attended his funeral.

, the assistant editor of The Academy

and later repudiated by Douglas), Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940); and a memoir, The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas (1931).

Douglas also was the editor of a literary journal, The Academy

, from 1907 to 1910, and during this time he had an affair with artist Romaine Brooks

, who was also bisexual (the main love of her life, Natalie Clifford Barney

, also had an affair with Wilde's niece Dorothy). He published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

in 1919, one of the first English language

translations of the infamous anti-Semitic tract.

There are six biographies of Douglas. The earlier ones by Braybrooke and Freeman were not allowed to quote from Douglas’s copyright work, and De Profundis was unpublished. Later biographies were by Rupert Croft-Cooke, H. Montgomery Hyde (who also wrote about Oscar Wilde

), Douglas Murray

(who describes Braybrooke’s biography as "a rehash and exaggeration of Douglas’s book", i.e. his autobiography). The most recent is Alfred Douglas: A Poet's Life and His Finest Work by Caspar Wintermans

, from Peter Owen Publishers in 2007.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

author

Author

An author is broadly defined as "the person who originates or gives existence to anything" and that authorship determines responsibility for what is created. Narrowly defined, an author is the originator of any written work.-Legal significance:...

, poet

Poet

A poet is a person who writes poetry. A poet's work can be literal, meaning that his work is derived from a specific event, or metaphorical, meaning that his work can take on many meanings and forms. Poets have existed since antiquity, in nearly all languages, and have produced works that vary...

and translator, better known as the intimate friend and lover of the writer Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

. Much of his early poetry was Uranian

Uranian

frame|right|From [[John Addington Symonds]]' 1891 book A Problem in Modern Ethics.Uranian is a 19th century term that referred to a person of a third sex — originally, someone with "a female psyche in a male body" who is sexually attracted to men, and later extended to cover homosexual gender...

in theme, though he tended, later in life, to distance himself from both Wilde's influence and his own role as a Uranian poet

Uranian poetry

The Uranians were a small and somewhat clandestine group of male pederastic poets who published works between 1858 and 1930...

.

Early life and background

John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry GCVO was a Scottish nobleman, remembered for lending his name and patronage to the "Marquess of Queensberry rules" that formed the basis of modern boxing, for his outspoken atheism, and for his role in the downfall of author and playwright Oscar...

and his first wife, the former Sibyl Montgomery, Douglas was born at Ham Hill House in Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

. He was his mother's favourite child; she called him Bosie (a derivative of Boysie), a nickname

Nickname

A nickname is "a usually familiar or humorous but sometimes pointed or cruel name given to a person or place, as a supposedly appropriate replacement for or addition to the proper name.", or a name similar in origin and pronunciation from the original name....

which stuck for the rest of his life.

Douglas was educated at Winchester College

Winchester College

Winchester College is an independent school for boys in the British public school tradition, situated in Winchester, Hampshire, the former capital of England. It has existed in its present location for over 600 years and claims the longest unbroken history of any school in England...

(1884–88) and at Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. As of 2006 the college had an estimated financial endowment of £153 million. Magdalen is currently top of the Norrington Table after over half of its 2010 finalists received first-class degrees, a record...

(1889–93), which he left without obtaining a degree. At Oxford, Douglas edited an undergraduate journal The Spirit Lamp (1892-3), an activity that intensified the constant conflict between him and his father. Their relationship had always been a strained one and during the Queensberry-Wilde feud, Douglas sided with Wilde, even encouraging him to prosecute his own father for libel. In 1893, Douglas had a brief affair with George Ives

George Cecil Ives

George Ives was a German-English poet, writer, penal reformer and early gay rights campaigner.-Life and career:...

.

In 1860, Douglas's grandfather, the 8th Marquess of Queensberry

Archibald Douglas, 8th Marquess of Queensberry

Archibald William Douglas, 8th Marquess of Queensberry PC , styled Viscount Drumlanrig between 1837 and 1856, was a Scottish Conservative Party politician...

, had died in what was reported as a shooting accident, but his death was widely believed to have been suicide. In 1862, his widowed grandmother, Lady Queensberry, converted to Roman Catholicism and took her children to live in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

.

Apart from the violent death of his grandfather, there were other tragedies in Douglas's family. One of his uncles, Lord James Douglas, was deeply attached to his twin sister 'Florrie

Lady Florence Dixie

Lady Florence Caroline Dixie , before her marriage Lady Florence Douglas, was a British traveller, war correspondent, writer and feminist.-Early life:...

' and was heartbroken when she married. In 1885, he tried to abduct a young girl, and after that became ever more manic. In 1888, Lord James married, but this proved disastrous. Separated from Florrie, James drank himself into a deep depression, and in 1891 committed suicide

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often committed out of despair or attributed to some underlying mental disorder, such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, alcoholism, or drug abuse...

by cutting his throat. Another of his uncles, Lord Francis Douglas

Lord Francis Douglas

Lord Francis William Bouverie Douglas was a novice, British mountaineer. After sharing in the first ascent of the Matterhorn, he died in a fall on the way down from the summit.-Early life:...

(1847–1865) had died in a climbing accident on the Matterhorn

Matterhorn

The Matterhorn , Monte Cervino or Mont Cervin , is a mountain in the Pennine Alps on the border between Switzerland and Italy. Its summit is 4,478 metres high, making it one of the highest peaks in the Alps. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points...

, while his uncle Lord Archibald Edward Douglas (1850–1938) became a clergyman. (Alfred Douglas's only child was in turn to go mad, and died in a mental hospital.)

Alfred Douglas's aunt, Lord James's twin Lady Florence Douglas

Lady Florence Dixie

Lady Florence Caroline Dixie , before her marriage Lady Florence Douglas, was a British traveller, war correspondent, writer and feminist.-Early life:...

(1855–1905), was an author, war correspondent

War correspondent

A war correspondent is a journalist who covers stories firsthand from a war zone. In the 19th century they were also called Special Correspondents.-Methods:...

for the Morning Post

Morning Post

The Morning Post, as the paper was named on its masthead, was a conservative daily newspaper published in London from 1772 to 1937, when it was acquired by The Daily Telegraph.- History :...

during the First Boer War

First Boer War

The First Boer War also known as the First Anglo-Boer War or the Transvaal War, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881-1877 annexation:...

, and a feminist

Feminism

Feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights and equal opportunities for women. Its concepts overlap with those of women's rights...

. In 1890, she published a novel, Gloriana, or the Revolution of 1900, in which women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage or woman suffrage is the right of women to vote and to run for office. The expression is also used for the economic and political reform movement aimed at extending these rights to women and without any restrictions or qualifications such as property ownership, payment of tax, or...

is achieved after a woman posing as a man named Hector l'Estrange is elected to the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

. The character l'Estrange is clearly based on Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

.

Relationship with Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

; although the playwright was married with two sons, they soon began an affair. In 1894, the Robert Hichens novel The Green Carnation

The Green Carnation

The Green Carnation, first published anonymously in 1894, was a scandalous novel by Robert Hichens whose lead characters are closely based on Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas - also known as 'Bosie', whom the author personally knew...

was published. Said to be a roman a clef

Roman à clef

Roman à clef or roman à clé , French for "novel with a key", is a phrase used to describe a novel about real life, overlaid with a façade of fiction. The fictitious names in the novel represent real people, and the "key" is the relationship between the nonfiction and the fiction...

based on the relationship of Wilde and Douglas, it would be one of the texts used against Wilde during his trials in 1895.

Douglas, known to his friends as 'Bosie', has been described as spoiled, reckless, insolent and extravagant. He would spend money on boys and gambling and expected Wilde to contribute to his tastes. They often argued and broke up, but would also always reconcile.

Douglas had praised Wilde's play Salome

Salome (play)

Salome is a tragedy by Oscar Wilde.The original 1891 version of the play was in French. Three years later an English translation was published...

in the Oxford magazine, The Spirit Lamp, of which he was editor (and used as a covert means of gaining acceptance for homosexuality). Wilde had originally written Salomé in French, and in 1893 he commissioned Douglas to translate it into English. Douglas's French was very poor and his translation was highly criticised: a passage that goes "On ne doit regarder que dans les miroirs" (French for "One should only look in mirrors") was translated as "One must not look at mirrors". Douglas's temper would not accept Wilde's criticism and he claimed that the errors were really in Wilde's original play. This led to a hiatus in the relationship and a row between the two men, with angry messages being exchanged and even the involvement of the publisher John Lane

John Lane (publisher)

-Biography:Originally from Devon, where he was born into a farming family, Lane moved to London already in his teens. While working as a clerk at the Railway Clearing House, he acquired knowledge as an autodidact....

and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley was an English illustrator and author. His drawings, done in black ink and influenced by the style of Japanese woodcuts, emphasized the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic. He was a leading figure in the Aesthetic movement which also included Oscar Wilde and James A....

when they themselves objected to Douglas's work. Beardsley complained to Robbie Ross: "For one week the numbers of telegraph and messenger boys who came to the door was simply scandalous". Wilde redid much of the translation himself, but, in a gesture of reconciliation, suggested that Douglas be dedicated as the translator rather than them sharing their names on the title-page. Accepting this, Douglas, in his vanity, compared a dedication to sharing the title-page as "the difference between a tribute of admiration from an artist and a receipt from a tradesman."

On another occasion, while staying together in Brighton

Brighton

Brighton is the major part of the city of Brighton and Hove in East Sussex, England on the south coast of Great Britain...

, Douglas fell ill with influenza

Influenza

Influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae , that affects birds and mammals...

and was nursed back to health by Wilde, but failed to return the favour when Wilde fell ill as well. Instead Douglas moved to the Grand Hotel and, on Wilde's 40th birthday, sent him a letter saying that he had charged him the bill. Douglas also gave his old clothes to male prostitutes, but failed to remove incriminating letters exchanged between him and Wilde, which were then used for blackmail

Blackmail

In common usage, blackmail is a crime involving threats to reveal substantially true or false information about a person to the public, a family member, or associates unless a demand is met. It may be defined as coercion involving threats of physical harm, threat of criminal prosecution, or threats...

.

Alfred's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, quickly suspected the liaison to be more than a friendship. He sent his son a letter, attacking him for leaving Oxford without a degree and failing to take up a proper career, such as a civil servant or lawyer. He threatened to "disown [Alfred] and stop all money supplies". Alfred responded with a telegram stating: "What a funny little man you are".

Queensberry was infuriated by this attitude. In his next letter he threatened his son with a "thrashing" and accused him of being "crazy". He also threatened to "make a public scandal in a way you little dream of" if he continued his relationship with Wilde.

Queensberry was well-known for his temper and threatening to beat people with a horsewhip. Alfred sent his father a postcard stating "I detest you" and making it clear that he would take Wilde's side in a fight between him and the Marquess, "with a loaded revolver".

In answer Queensberry wrote to Alfred (whom he addressed as "You miserable creature") that he had divorced Alfred's mother in order not to "run the risk of bringing more creatures into the world like yourself" and that, when Alfred was a baby, "I cried over you the bitterest tears a man ever shed, that I had brought such a creature into the world, and unwittingly committed such a crime... You must be demented".

When Douglas' eldest brother, Lord Drumlanrig

Francis Douglas, Viscount Drumlanrig

Francis Archibald Douglas, Viscount Drumlanrig , also 1st Baron Kelhead in his own right, was a Scottish nobleman and Liberal politician.-Background and education:...

, heir to the marquessate of Queensberry, died in a suspicious hunting accident in October 1894, rumours circulated that Drumlanrig had been having a homosexual relationship with the Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

, Lord Rosebery

Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery

Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, KG, PC was a British Liberal statesman and Prime Minister. Between the death of his father, in 1851, and the death of his grandfather, the 4th Earl, in 1868, he was known by the courtesy title of Lord Dalmeny.Rosebery was a Liberal Imperialist who...

. The elder Queensberry thus embarked on a campaign to save his other son, and began a public persecution of Wilde. He and a minder confronted the playwright in his own home; later, Queensberry planned to throw rotten vegetables at Wilde during the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest

The Importance of Being Earnest

The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People is a play by Oscar Wilde. First performed on 14 February 1895 at St. James's Theatre in London, it is a farcical comedy in which the protagonists maintain fictitious personae in order to escape burdensome social obligations...

, but, forewarned of this, the playwright was able to deny him access to the theatre.

Visiting card

A visiting card, also known as a calling card, is a small paper card with one's name printed on it. They first appeared in China in the 15th century, and in Europe in the 17th century...

on which he had written: "For Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite"–a misspelling of "sodomite." The wording is in dispute – the handwriting is unclear – although Hyde reports it as this. According to Merlin Holland, Wilde's grandson, it is more likely "Posing somdomite," while Queensberry himself claimed it to be "Posing as somdomite." Holland suggests that this wording ("posing [as] ...") would have been easier to defend in court.

The 1895 trials

In response to this card, and with Douglas's avid support, but against the advice of friends such as Robert RossRobert Baldwin Ross

Robert Baldwin "Robbie" Ross was a Canadian journalist and art critic. He is best known as the executor of the estate of Oscar Wilde, to whom he had been a lifelong friend. He was also responsible for bringing together several great literary figures, such as Siegfried Sassoon, and acting as their...

, Frank Harris

Frank Harris

Frank Harris was a Irish-born, naturalized-American author, editor, journalist and publisher, who was friendly with many well-known figures of his day...

, and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

, Wilde had Queensberry arrested and charged with criminal libel in a private prosecution

Private prosecution

A private prosecution is a criminal proceeding initiated by an individual or private organisation instead of by a public prosecutor who represents the state...

, as sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

was then a crime. Several highly suggestive erotic letters that Wilde had written to Douglas were introduced into evidence; he claimed that they were works of art. Wilde was closely questioned about the homoerotic themes in The Picture of Dorian Gray

The Picture of Dorian Gray

The Picture of Dorian Gray is the only published novel by Oscar Wilde, appearing as the lead story in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine on 20 June 1890, printed as the July 1890 issue of this magazine...

and in The Chameleon, a single-issue magazine published by Douglas to which he had contributed a short article. Queensberry's lawyer portrayed Wilde as a vicious older man who habitually preyed upon naive young boys and seduced them into a life of homosexuality with extravagant gifts and promises of a glamorous lifestyle.

Queensberry's attorney announced in court that he had located several male prostitutes who were to testify that they had had sex with Wilde. Wilde then dropped the libel charge, on his lawyers' advice, as a conviction was very unlikely if the libel were demonstrated in court to be true. Based on the evidence raised during the case, Wilde was arrested the next day and charged with committing sodomy

Sodomy

Sodomy is an anal or other copulation-like act, especially between male persons or between a man and animal, and one who practices sodomy is a "sodomite"...

and "gross indecency

Gross indecency

Gross indecency is a UK and Canadian legal term of art which was used in the definition of the following criminal offences:*Gross indecency between men, contrary to section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 and later contrary to section 13 of the Sexual Offences Act 1956.*Indecency with a...

", a vague charge which covered all homosexual acts other than sodomy.

Douglas's 1892 poem Two Loves, which was used against Wilde at the latter's trial, ends with the famous line that refers to homosexuality

Homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic or sexual attraction or behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality refers to "an enduring pattern of or disposition to experience sexual, affectional, or romantic attractions" primarily or exclusively to people of the same...

as the love that dare not speak its name

The love that dare not speak its name

The love that dare not speak its name is a phrase from the poem "Two Loves" by Lord Alfred Douglas, published in 1894. It was mentioned at Oscar Wilde's gross indecency trial, and it is classically interpreted as a euphemism for homosexuality.-See also:...

. Wilde gave an eloquent but counterproductive explanation of the nature of this love on the witness stand. The trial resulted in a hung jury

Hung jury

A hung jury or deadlocked jury is a jury that cannot, by the required voting threshold, agree upon a verdict after an extended period of deliberation and is unable to change its votes due to severe differences of opinion.- England and Wales :...

.

In 1895, when during his trials Wilde was released on bail

Bail

Traditionally, bail is some form of property deposited or pledged to a court to persuade it to release a suspect from jail, on the understanding that the suspect will return for trial or forfeit the bail...

, Douglas's cousin Sholto Johnstone Douglas

Sholto Johnstone Douglas

Robert Sholto Johnstone Douglas , known as Sholto Douglas, or more formally as Sholto Johnstone Douglas, was a Scottish figurative artist, a painter chiefly of portraits and landscapes....

stood surety

Surety

A surety or guarantee, in finance, is a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults...

for £

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

500 of the bail money.

The prosecutor opted to retry the case. Wilde was convicted on 25 May 1895 and sentenced to two years' hard labour, first at Pentonville

Pentonville (HM Prison)

HM Prison Pentonville is a Category B/C men's prison, operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not actually within Pentonville itself, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury area of the London Borough of Islington, in inner-North London,...

, then Wandsworth

Wandsworth (HM Prison)

HM Prison Wandsworth is a Category B men's prison at Wandsworth in the London Borough of Wandsworth, south west London, England. It is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service and is the largest prison in London and one of the largest in western Europe, with similar capacity to Liverpool...

, then famously in Reading Gaol. Douglas was forced into exile in Europe.

While in prison, Wilde wrote Douglas a very long and critical letter entitled De Profundis

De Profundis (letter)

De Profundis is an epistle written by Oscar Wilde during his imprisonment in Reading Gaol, to Lord Alfred Douglas. During its first half Wilde recounts their previous relationship and extravagant lifestyle which eventually led to Wilde's conviction and imprisonment for gross indecency...

, describing exactly what he felt about him, which Wilde was not permitted to send, but which may or may not have been sent to Douglas after Wilde's release.

Following Wilde's release (19 May 1897), the two reunited in August at Rouen

Rouen

Rouen , in northern France on the River Seine, is the capital of the Haute-Normandie region and the historic capital city of Normandy. Once one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe , it was the seat of the Exchequer of Normandy in the Middle Ages...

, but stayed together only a few months owing to personal differences and the various pressures on them.

Naples and Paris

This meeting was disapproved of by the friends and families of both men. During the later part of 1897, Wilde and Douglas lived together near NaplesNaples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

, but for financial and other reasons, they separated. Wilde lived the remainder of his life primarily in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, and Douglas returned to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

in late 1898.

The period when the two men lived in Naples would later become quite controversial. Wilde claimed that Douglas had offered a home, but had no funds or ideas. When Douglas eventually did gain funds from his late father's estate, he refused to grant Wilde a permanent allowance, although he did give him occasional handouts. When Wilde died in 1900, he was relatively impoverished. Douglas served as chief mourner, although there reportedly was an altercation at the gravesite between him and Robert Ross

Robert Baldwin Ross

Robert Baldwin "Robbie" Ross was a Canadian journalist and art critic. He is best known as the executor of the estate of Oscar Wilde, to whom he had been a lifelong friend. He was also responsible for bringing together several great literary figures, such as Siegfried Sassoon, and acting as their...

. This struggle would preview the later litigations between the two former lovers of Oscar Wilde.

Marriage

After Wilde's death, Douglas established a close friendship with Olive Eleanor CustanceOlive Custance

Olive Eleanor Custance was a British poet. She was part of the aesthetic movement of the 1890s, and a contributor to The Yellow Book....

, an heiress and poet. They married on 4 March 1902 and had one son, Raymond Wilfred Sholto Douglas (17 November 1902 - 10 October 1964) who was diagnosed with a schizo-affective disorder at the age of 24, and died unmarried, in a mental hospital.

Repudiation of Wilde

More than a decade after Wilde's death, with the release of suppressed portions of Wilde's De Profundis letter in 1912, Douglas turned against his former friend, whose homosexuality he grew to condemn. He was a defence witness in the libel case brought by Maud AllanMaud Allan

Maud Allan was a pianist-turned-actor, dancer and choreographer remembered for her "famously impressionistic mood settings".- Early life :...

against Noel Pemberton Billing

Noel Pemberton Billing

Noel Pemberton Billing was an English aviator, inventor, publisher, and Member of Parliament. He founded the firm that became Supermarine and promoted air power, but he held a strong antipathy towards the Royal Aircraft Factory and its products...

in 1918. Billing had accused Allan, who was performing Wilde's play Salome

Salome (play)

Salome is a tragedy by Oscar Wilde.The original 1891 version of the play was in French. Three years later an English translation was published...

, of being part of a homosexual conspiracy to undermine the war effort. Douglas also contributed to Billing's journal Vigilante as part of his campaign against Robert Ross. He had written a poem referring to Margot Asquith "bound with Lesbian fillets" while her husband Herbert

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916...

, the Prime Minister, gave money to Ross. During the trial he described Wilde as "the greatest force for evil that has appeared in Europe during the last three hundred and fifty years". Douglas added that he intensely regretted having met Wilde, and having helped him with the translation of Salome which he described as "a most pernicious and abominable piece of work".

Libel actions

Douglas started his "litigious and libellous career" by obtaining an apology and fifty guineas each from the Oxford and Cambridge university magazines The IsisIsis magazine

The Isis Magazine was established at Oxford University in 1892 . Traditionally a rival to the student newspaper Cherwell, it was finally acquired by the latter's publishing house, OSPL, in the late 1990s...

and Cambridge for defamatory references to him in an article on Wilde.

He was a plaintiff and defendant in several trials for civil or criminal libel

Criminal libel

Criminal libel is a legal term, of English origin, which may be used with one of two distinct meanings, in those common law jurisdictions where it is still used....

. In 1913 he accused Arthur Ransome

Arthur Ransome

Arthur Michell Ransome was an English author and journalist, best known for writing the Swallows and Amazons series of children's books. These tell of school-holiday adventures of children, mostly in the Lake District and the Norfolk Broads. Many of the books involve sailing; other common subjects...

of libelling him in his book Oscar Wilde: A Critical Study. He saw this trial as a weapon against his enemy Ross, not understanding that Ross would not be called to give evidence. In a similar way he had not appreciated the fact that his father's character would not be an issue when he urged Wilde to sue back in 1895. The court found in Ransome's favour. Ransome did remove the offending passages from the 2nd edition of his book.

In the most noted case, brought by Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in 1923, Douglas was found guilty of libelling Churchill and was sentenced to six months in prison. Douglas had claimed that Churchill had been part of a Jewish conspiracy to kill Lord Kitchener, the British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Secretary of State for War

Secretary of State for War

The position of Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a British cabinet-level position, first held by Henry Dundas . In 1801 the post became that of Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. The position was re-instated in 1854...

. Kitchener had died on 5 June 1916, while on a diplomatic mission to Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

: the ship in which he was travelling, the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire

HMS Hampshire (1903)

HMS Hampshire was a Devonshire-class armoured cruiser of the Royal Navy. She was built by Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick, Tyne and Wear and commissioned in 1905 at a cost of £833,817....

, struck a German naval mine

Naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an enemy vessel...

and sank west of the Orkney Islands

Orkney Islands

Orkney also known as the Orkney Islands , is an archipelago in northern Scotland, situated north of the coast of Caithness...

. In spite of this libel claim, Douglas wrote a sonnet

Sonnet

A sonnet is one of several forms of poetry that originate in Europe, mainly Provence and Italy. A sonnet commonly has 14 lines. The term "sonnet" derives from the Occitan word sonet and the Italian word sonetto, both meaning "little song" or "little sound"...

in praise of Churchill in 1941.

In 1924, while in prison, Douglas, in an ironic echo of Wilde's composition of De Profundis (Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

for "From the Depths") during his incarceration, wrote his last major poetic work, In Excelsis (literally, "In the highest"), which contains 17 canto

Canto

The canto is a principal form of division in a long poem, especially the epic. The word comes from Italian, meaning "song" or singing. Famous examples of epic poetry which employ the canto division are Lord Byron's Don Juan, Valmiki's Ramayana , Dante's The Divine Comedy , and Ezra Pound's The...

s. Since the prison authorities would not allow Douglas to take the manuscript with him when he was released, he had to rewrite the entire work from memory.

Douglas maintained that his health never recovered from his harsh prison ordeal, which included sleeping on a plank bed without a mattress.

Later life

In 1911, Douglas embraced Roman Catholicism, as Oscar Wilde had also done earlier.Following his own incarceration in prison in 1924, Douglas's feelings toward Oscar Wilde began to soften considerably. He said in Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up that “Sometimes a sin is also a crime (for example, a murder or theft) but this is not the case with homosexuality, any more than with adultery”.

Throughout the 1930s and until his death, Douglas maintained correspondences with many people, including Marie Stopes

Marie Stopes

Marie Carmichael Stopes was a British author, palaeobotanist, campaigner for women's rights and pioneer in the field of birth control...

and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for drama, and he wrote more than 60...

. Anthony Wynn

Anthony Wynn

Anthony Wynn is an American author and playwright.-Playwright:Wynn's two-act, two-actor drama Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship, explores the complex relationship between playwright George Bernard Shaw and poet Lord Alfred "Bosie" Douglas. It is based on correspondence exchanged...

wrote the play Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship based on the letters between Shaw and Douglas. One of Douglas's final public appearances was his well-received lecture to the Royal Society of Literature

Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature is the "senior literary organisation in Britain". It was founded in 1820 by George IV, in order to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". The Society's first president was Thomas Burgess, who later became the Bishop of Salisbury...

on 2 September 1943, entitled The Principles of Poetry, which was published in an edition of 1,000 copies. He attacked the poetry of T. S. Eliot

T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns "T. S." Eliot OM was a playwright, literary critic, and arguably the most important English-language poet of the 20th century. Although he was born an American he moved to the United Kingdom in 1914 and was naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at age 39.The poem that made his...

, and the talk was praised by Arthur Quiller-Couch

Arthur Quiller-Couch

Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch was a Cornish writer, who published under the pen name of Q. He is primarily remembered for the monumental Oxford Book Of English Verse 1250–1900 , and for his literary criticism...

and Augustus John

Augustus John

Augustus Edwin John OM, RA, was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a short time around 1910, he was an important exponent of Post-Impressionism in the United Kingdom....

.

Douglas's only child, Raymond, was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is a psychiatric diagnosis that describes a mental disorder characterized by recurring episodes of elevated or depressed mood, or of simultaneously elevated and depressed mood, that alternate with, or occur together with, distortions in perception.Schizoaffective disorder...

in 1927 and entered St Andrew's Hospital

St Andrew's Hospital

St Andrew's Hospital in Northampton, England is a psychiatric hospital run by a non-profit-making, charitable trust. It is by far the largest mental health facility in UK, providing national specialist services for adolescents, men, women and older people with mental illness, learning disability,...

, a mental institution. He was decertified and released after five years, but suffered a subsequent breakdown and returned to the hospital. When his mother, Olive Douglas, died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 67, Raymond was able to attend her funeral and in June he was again decertified and released. However, his conduct rapidly deteriorated and he returned to St Andrew's in November where he stayed until his death on 10 October 1964.

Death

Douglas died of congestive heart failureCongestive heart failure

Heart failure often called congestive heart failure is generally defined as the inability of the heart to supply sufficient blood flow to meet the needs of the body. Heart failure can cause a number of symptoms including shortness of breath, leg swelling, and exercise intolerance. The condition...

at Lancing

Lancing, West Sussex

Lancing is a town and civil parish in the Adur district of West Sussex, England, on the western edge of the Adur Valley. It lies on the coastal plain between Sompting to the west, Shoreham-by-Sea to the east and the parish of Coombes to the north...

in West Sussex on 20 March 1945 at the age of 74. He was buried on 23 March at the Franciscan Monastery

Friary Church of St Francis and St Anthony, Crawley

The Friary Church of St Francis and St Anthony is a Roman Catholic church in Crawley, a town and borough in West Sussex, England. The town's first permanent place of Roman Catholic worship was founded in 1861 next to a friary whose members, from the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, had been invited...

, Crawley

Crawley

Crawley is a town and local government district with Borough status in West Sussex, England. It is south of Charing Cross, north of Brighton and Hove, and northeast of the county town of Chichester, covers an area of and had a population of 99,744 at the time of the 2001 Census.The area has...

, West Sussex, where he is interred alongside his mother, Sibyl, Marchioness of Queensberry, who died on 31 October 1935 at the age of 91. A single gravestone covers them both. The elderly Douglas, living in reduced circumstances in Hove

Hove

Hove is a town on the south coast of England, immediately to the west of its larger neighbour Brighton, with which it forms the unitary authority Brighton and Hove. It forms a single conurbation together with Brighton and some smaller towns and villages running along the coast...

in the 1940s, is mentioned in the Diaries of Chips Channon and the first autobiography of Sir Donald Sinden, both of whom attended his funeral.

Writings

Douglas published several volumes of poetry; two books about his relationship with Wilde, Oscar Wilde and Myself (1914; largely ghostwritten by T.W.H. CroslandThomas William Hodgson Crosland

Thomas William Hodgson Crosland , was a British author, poet, journalist and friend of royalty.-Biography:He was born in Leeds on July 21, 1865 or 1868 ....

, the assistant editor of The Academy

The Academy (periodical)

The Academy was a review of literature and general topics published in London from 1869 to 1902, founded by Charles Appleton.The first issue was published on 9 October 1869 under the title The Academy: A Monthly Record of Literature, Learning, Science, and Art. It was published monthly from Oct....

and later repudiated by Douglas), Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940); and a memoir, The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas (1931).

Douglas also was the editor of a literary journal, The Academy

The Academy (periodical)

The Academy was a review of literature and general topics published in London from 1869 to 1902, founded by Charles Appleton.The first issue was published on 9 October 1869 under the title The Academy: A Monthly Record of Literature, Learning, Science, and Art. It was published monthly from Oct....

, from 1907 to 1910, and during this time he had an affair with artist Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks

Romaine Brooks, born Beatrice Romaine Goddard , was an American painter who worked mostly in Paris and Capri. She specialized in portraiture and used a subdued palette dominated by the color gray...

, who was also bisexual (the main love of her life, Natalie Clifford Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney

Natalie Clifford Barney was an American playwright, poet and novelist who lived as an expatriate in Paris....

, also had an affair with Wilde's niece Dorothy). He published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is a fraudulent, antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for achieving global domination. It was first published in Russia in 1903, translated into multiple languages, and disseminated internationally in the early part of the twentieth century...

in 1919, one of the first English language

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

translations of the infamous anti-Semitic tract.

There are six biographies of Douglas. The earlier ones by Braybrooke and Freeman were not allowed to quote from Douglas’s copyright work, and De Profundis was unpublished. Later biographies were by Rupert Croft-Cooke, H. Montgomery Hyde (who also wrote about Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish writer and poet. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of London's most popular playwrights in the early 1890s...

), Douglas Murray

Douglas Murray (author)

Douglas Murray is a British writer and commentator who was the director of the Centre for Social Cohesion from 2007 until 2011 and is currently an associate director of the Henry Jackson Society. Murray appears regularly in the British broadcast media, commentating on issues from a conservative...

(who describes Braybrooke’s biography as "a rehash and exaggeration of Douglas’s book", i.e. his autobiography). The most recent is Alfred Douglas: A Poet's Life and His Finest Work by Caspar Wintermans

Caspar Wintermans

Caspar Wintermans is an author and scholar. He studied art history and archaeology at Leiden University. Much of his work has centered on Lord Alfred Douglas, poet and intimate friend of Oscar Wilde. His published works include Halcyon Days: Contributions to The Spirit Lamp, Dear Sir: Letters of...

, from Peter Owen Publishers in 2007.

Poetry

- Poems (1896)

- Tails with a Twist 'by a Belgian Hare' (1898)

- The City of the Soul (1899)

- The Duke of Berwick (1899)

- The Placid Pug (1906)

- The Pongo Papers and the Duke of Berwick (1907)

- Sonnets (1909)

- The Collected Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas (1919)

- In Excelsis (1924)

- The Complete Poems of Lord Alfred Douglas (1928)

- Sonnets (1935)

- Lyrics (1935)

- The Sonnets of Lord Alfred Douglas (1943)

Non-fiction

- Oscar Wilde and Myself (1914) (ghost-written by T. W. H. Crosland )

- Foreword to New Preface to the 'Life and Confessions of Oscar Wilde by Frank Harris (1925)

- Introduction to Songs of Cell by Horatio Bottomley (1928)

- The Autobiography of Lord Alfred Douglas (1929; 2nd ed. 1931)

- My Friendship with Oscar Wilde (1932; retitled American version of his memoir)

- The True History of Shakespeare's Sonnets (1933)

- Introduction to The Pantomime Man by Richard Middleton (1933)

- Preface to Bernard Shaw, Frank Harris, and Oscar Wilde by Robert Harborough Sherard (1937)

- Without Apology (1938)

- Preface to Oscar Wilde: A PlayOscar Wilde (play)The play Oscar Wilde, written by Leslie & Sewell Stokes, is based on the life of the Irish playwright Oscar Wilde in which Wilde's friend, the controversial author and journalist Frank Harris, appears as a character...

by Leslie StokesLeslie StokesLeslie Stokes was an English playwright and BBC radio producer and director.As a young man Leslie Stokes was an actor and later became a playwright and BBC radio producer and director. Together with his brother, author and playwright Sewell Stokes, he co-wrote a number of plays, including the...

& Sewell StokesSewell StokesFrancis Martin Sewell Stokes was an English novelist, biographer, playwright, screenwriter, broadcaster and prison visitor. He collaborated on a number of occasions with his brother, Leslie Stokes, an actor and later in life a BBC radio producer, with whom he shared a flat for many years...

(1938) - Introduction to Brighton Aquatints by John Piper (1939)

- Ireland and the War Against Hitler (1940)

- Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940)

- Introduction to Oscar Wilde and the Yellow Nineties by Frances Winwar (1941)

- The Principles of Poetry (1943)

- Preface to Wartime Harvest by Marie Carmichael Stopes (1944)