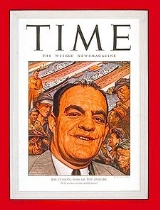

Joseph Curran

Encyclopedia

This article is about Joseph Curran, an American labor leader. For information about the state attorney general in Maryland, see J. Joseph Curran, Jr.

Joseph Curran (March 1, 1906 - August 14, 1981) was a merchant seaman

and an American

labor

leader. He was founding president of the National Maritime Union

(or NMU, now part of the Seafarers International Union of North America

) from 1937 to 1973, and a vice president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

(CIO).

. His father died when he was two years old, and his mother boarded with another family. He attended parochial school

, but when he was 14 he was expelled during the seventh grade for truancy

.

He worked as a caddy

and factory worker before finding employment in 1922 in the United States Merchant Marine

. He worked as an able seaman

and boatswain

, washing dishes in restaurants when not at sea and sleeping on a Battery Park bench at night. It was during this time that he received his lifelong nickname "Big Joe."

Curran joined the International Seamen's Union

(or ISU; the remnants of which would become the Seafarers International Union), but was not active in the union at first.

. Curran and the crew of the Panama Pacific Line's California went on strike

at sailing time and refused to cast off the lines unless wages were increased and overtime paid.

The strike was essentially a sitdown strike

. Curran and the crew refused to leave the ship, for the owners would have simply replaced them with strikebreakers. The crew remained aboard and continued to do all their duties except cast off the lines. The California remained tied up for three days.

Finally, United States Secretary of Labor

Frances Perkins

personally intervened in the California strike. Speaking to the crew by telephone, Perkins agreed to arrange a grievance hearing once the ship docked at its destination in New York City

, and that there would be no reprisals by the company or government against Curran or the strikers.

During the California's return trip, the Panama Pacific Line raised wages by $5 a month to $60 per month.

But Perkins was unable to follow through on her other promises. United States Secretary of Commerce

Daniel Roper

and the Panama Pacific Line declared Curran and the strikers mutineers

. The line even took out national advertising attacking Curran. When the ship docked, Federal Bureau of Investigation

agents met the ship and began an investigation into the "mutiny." Curran and other top strike leaders were fined two day's pay, fired and blacklist

ed. Perkins was able to keep the strikers from being prosecuted for mutiny, however.

Seaman all along the East Coast struck to protest the treatment of the California's crew. Curran became a leader of the 10-week strike, eventually forming a supportive association known as the Seamen's Defense Committee.

The S.S. California strike was only part of a worldwide wave of unrest among American seamen. A series of port and shipboard strikes broke out in 1936 and 1937 in the Atlantic

The S.S. California strike was only part of a worldwide wave of unrest among American seamen. A series of port and shipboard strikes broke out in 1936 and 1937 in the Atlantic

and Gulf of Mexico

. In October 1936, Curran called a second strike, in part to improve working conditions and in part to embarrass the ISU. The four-month strike idled 50,000 seamen and 300 ships.

Curran, believing it was time to abandon the conservation International Seamen's Union, began to sign up members for a new, rival union. The level of organizing was so intense that hundreds of ships delayed their sailing time as seamen listened to organizers and signed union cards.

In May 1937, Curran and other leaders of his nascent movement formed the National Maritime Union. The Seamen's Defense Committee reconstituted itself as a union. It held its first convention in July, and 30,000 seamen switched their membership from the ISU to the NMU. Curran was elected president of the new organization. Elected secretary-treasurer of the union was Jamaica

n-born Ferdinand Smith. Thus, from its inception NMU was racially integrated. Within six years, nearly all racial discrimination was eliminated in hiring, wages, living accommodations and work assignments.

A hallmark of the new union was the formation of hiring halls in each port. The hiring halls ensured a steady supply of experienced seamen for passenger and cargo ships, and reduced the corruption which plagued the hiring of able seamen. The hiring halls also worked to combat racial discrimination and promote racial harmony among maritime workers.

Within a year, the NMU had more than 50,000 members, and most American shippers were under contract. Stripped of most of its membership, the ISU became almost moribund.

In July 1937, Curran and other seamen's union leaders were invited by John L. Lewis

to come to Washington, D.C.

, to form a major organizing drive among ship and port workers. The unions comprising the CIO had been ejected by the American Federation of Labor

(AFL) in November 1936, and now Lewis wanted to launch a maritime union. His goal was to create, out of the 300,000 maritime industry's workers, a union as large and influential as the Steel Workers Organizing Committee

. Although Lewis favored Harry Bridges

, president of the Pacific Coast District of the International Longshoremen's Association

, to lead the new maritime industrial union, the other union leaders balked. Curran agreed to affiliate with the CIO, but refused to let Bridges or anyone else take over his union. His views were reflected among those of the other union leaders, and the CIO's maritime industrial union never got off the ground.

Curran was a vociferous advocate of maritime workers' rights. When Joseph P. Kennedy advocated legislation to outlaw maritime strikes and make arbitration of labor disputes compulsory, Curran called him a "union wrecker". When Kennedy was under consideration as executive director of the United Seamen's Service (an association which assists, feeds and houses American merchant seamen overseas), Curran successfully opposed the multi-millionaire's candidacy. Curran put such pressure on Kennedy that on February 18, 1938, Kennedy resigned as chair of the United States Maritime Commission

.

Curran was also a strong supporter of far-left-wing causes. In August 1940, he urged unions in the New York City area to support an "emergency peace mobilization" opposing U.S. entry into the war in Europe.

In 1940, Curran was elected a vice president of the CIO. When the CIO and AFL merged in 1955, he was appointed a vice president of the merged organization as well.

The Greater New York Industrial Union (GNYIU) was organized by the CIO in 1940 as a central labor body for New York City

. CIO-affiliated local unions in New York City and the nearby vicinity were its primary members. At the organization's founding convention on July 24, 1940, Curran was elected president of GNYIU. Saul Kills, a member of the American Newspaper Guild, was elected its secretary-treasurer. The organization had 250 local union affiliates, representing more than 500,000 workers.

By 1948, however, there were serious concerns about communist

infiltration of the GNYIU. The United States House of Representatives

appointed a special investigative subcommittee to look into the matter. Several CIO unions were investigated, including the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America

, the Teachers Union of the City of New York, the United Public Workers of America

and the Department Store Employees Union

.

CIO president Philip Murray

appointed a three-member board in October 1940 to forestall the House investigation. The board members reported to Murray that Curran, Kills and the GNYIU executive board had been advocating pro-communist policies. The GNYIU was on the verge of supporting Henry A. Wallace

in an independent bid for president as well. The national CIO executive board revoked the charter of the GNYIU in November 1940. Curran denied that he was a communist before both the CIO executive board and the Joint Commerce Committee of the U.S. Congress. Curran became increasingly anti-communist thereafter. In 1946, he pulled the NMU out of a Committee for Maritime Unity which was led by Harry Bridges. After World War II, he purged thousands of members and elected leaders he suspected of harboring communist sympathies.

For many years, he was chair of the AFL-CIO

's Maritime Committee. He was also co-chair of the Labor-Management Maritime Committee, a body established by AFL-CIO maritime unions and U.S. shipping companies to discuss and resolve labor issues.

Curran was also vice chairman of the Seafarer's Section of the International Transportworkers Federation, an international confederation of maritime unions.

Curran was also vice president of the United Seamen's Service.

.

By the mid-1960s, Curran was being criticized for ignoring his members' needs and concerns. His $85,000-a-year salary was one of the highest in the American labor movement even though his union was small and shedding members. He enjoyed an unlimited expense account, and traveled by chartered jet and private limousine. He cajoled the union's executive board into building a massive, Art Deco

headquarters in Manhattan, and had the edifice named after himself.

In 1966, with the surreptitious help of NMU staffers, union member James B. Morrissey challenged the results of Curran's 1966 re-election as fraudulent. The Department of Labor agreed, but a re-run election did not change the outcome.

In 1973, shortly after Curran won re-election for a thirteenth term as union president, Morrissey sued Curran and charged him with misappropriating union funds. In a precedent-setting ruling in Morrissey and Ibrahim v. Curran, 650 F.2d 1267

(1981), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit established a broad right for union members to sue union officers for improper financial practices.

Morrissey's barrage of lawsuits against Curran led Curran to retire suddenly on March 5, 1973. Long-time secretary-treasurer Shannon J. Wall

succeeded him as president.

Curran retired to Boca Raton, Florida

. He died there of cancer on August 14, 1981.

J. Joseph Curran, Jr.

J. Joseph Curran, Jr. is an American politician and the longest serving elected Attorney General in Maryland history. His son-in-law, Martin J. O'Malley, is the Governor of Maryland.-Background:...

Joseph Curran (March 1, 1906 - August 14, 1981) was a merchant seaman

Able Seaman (occupation)

An able seaman is an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination of these roles.-Watchstander:...

and an American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

labor

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

leader. He was founding president of the National Maritime Union

National Maritime Union

The National Maritime Union was an American labor union founded in May 1937. It affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations in July 1937...

(or NMU, now part of the Seafarers International Union of North America

Seafarers International Union of North America

The Seafarers International Union or SIU is an organization of 12 autonomous labor unions of mariners, fishermen and boatmen working aboard vessels flagged in the United States or Canada. Michael Sacco has been its president since 1988. The organization has an estimated 35,498 members and is the...

) from 1937 to 1973, and a vice president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations

Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations, or CIO, proposed by John L. Lewis in 1932, was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 required union leaders to swear that they were not...

(CIO).

Early life

Curran was born on Manhattan's Lower East SideLower East Side, Manhattan

The Lower East Side, LES, is a neighborhood in the southeastern part of the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is roughly bounded by Allen Street, East Houston Street, Essex Street, Canal Street, Eldridge Street, East Broadway, and Grand Street....

. His father died when he was two years old, and his mother boarded with another family. He attended parochial school

Parochial school

A parochial school is a school that provides religious education in addition to conventional education. In a narrower sense, a parochial school is a Christian grammar school or high school which is part of, and run by, a parish.-United Kingdom:...

, but when he was 14 he was expelled during the seventh grade for truancy

Truancy

Truancy is any intentional unauthorized absence from compulsory schooling. The term typically describes absences caused by students of their own free will, and usually does not refer to legitimate "excused" absences, such as ones related to medical conditions...

.

He worked as a caddy

Caddy

In golf, a caddy is the person who carries a player's bag and clubs, and gives insightful advice and moral support. A good caddy is aware of the challenges and obstacles of the golf course being played, along with the best strategy in playing it. This includes knowing overall yardage, pin...

and factory worker before finding employment in 1922 in the United States Merchant Marine

United States Merchant Marine

The United States Merchant Marine refers to the fleet of U.S. civilian-owned merchant vessels, operated by either the government or the private sector, that engage in commerce or transportation of goods and services in and out of the navigable waters of the United States. The Merchant Marine is...

. He worked as an able seaman

Able Seaman (occupation)

An able seaman is an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination of these roles.-Watchstander:...

and boatswain

Boatswain

A boatswain , bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun is an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. The boatswain supervises the other unlicensed members of the ship's deck department, and typically is not a watchstander, except on vessels with small crews...

, washing dishes in restaurants when not at sea and sleeping on a Battery Park bench at night. It was during this time that he received his lifelong nickname "Big Joe."

Curran joined the International Seamen's Union

International Seamen's Union

The International Seamen's Union was an American maritime trade union which operated from 1892 until 1937. In its last few years, the union effectively split into the National Maritime Union and Seafarer's International Union.-The early years:...

(or ISU; the remnants of which would become the Seafarers International Union), but was not active in the union at first.

"SS California" strike

In 1936, Curran led a strike aboard the ocean liner S.S. California, then docked in San Pedro, CaliforniaSan Pedro, Los Angeles, California

San Pedro is a port district of the city of Los Angeles, California, United States. It was annexed in 1909 and is a major seaport of the area...

. Curran and the crew of the Panama Pacific Line's California went on strike

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

at sailing time and refused to cast off the lines unless wages were increased and overtime paid.

The strike was essentially a sitdown strike

Sitdown strike

A sit-down strike is a form of civil disobedience in which an organized group of workers, usually employed at a factory or other centralized location, take possession of the workplace by "sitting down" at their stations, effectively preventing their employers from replacing them with strikebreakers...

. Curran and the crew refused to leave the ship, for the owners would have simply replaced them with strikebreakers. The crew remained aboard and continued to do all their duties except cast off the lines. The California remained tied up for three days.

Finally, United States Secretary of Labor

United States Secretary of Labor

The United States Secretary of Labor is the head of the Department of Labor who exercises control over the department and enforces and suggests laws involving unions, the workplace, and all other issues involving any form of business-person controversies....

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins

Frances Perkins , born Fannie Coralie Perkins, was the U.S. Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945, and the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. As a loyal supporter of her friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, she helped pull the labor movement into the New Deal coalition...

personally intervened in the California strike. Speaking to the crew by telephone, Perkins agreed to arrange a grievance hearing once the ship docked at its destination in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, and that there would be no reprisals by the company or government against Curran or the strikers.

During the California's return trip, the Panama Pacific Line raised wages by $5 a month to $60 per month.

But Perkins was unable to follow through on her other promises. United States Secretary of Commerce

United States Secretary of Commerce

The United States Secretary of Commerce is the head of the United States Department of Commerce concerned with business and industry; the Department states its mission to be "to foster, promote, and develop the foreign and domestic commerce"...

Daniel Roper

Daniel Calhoun Roper

Daniel Calhoun Roper was a U.S. administrator, particularly under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, born in Marlboro County, South Carolina...

and the Panama Pacific Line declared Curran and the strikers mutineers

Mutiny

Mutiny is a conspiracy among members of a group of similarly situated individuals to openly oppose, change or overthrow an authority to which they are subject...

. The line even took out national advertising attacking Curran. When the ship docked, Federal Bureau of Investigation

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation is an agency of the United States Department of Justice that serves as both a federal criminal investigative body and an internal intelligence agency . The FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crime...

agents met the ship and began an investigation into the "mutiny." Curran and other top strike leaders were fined two day's pay, fired and blacklist

Blacklist

A blacklist is a list or register of entities who, for one reason or another, are being denied a particular privilege, service, mobility, access or recognition. As a verb, to blacklist can mean to deny someone work in a particular field, or to ostracize a person from a certain social circle...

ed. Perkins was able to keep the strikers from being prosecuted for mutiny, however.

Seaman all along the East Coast struck to protest the treatment of the California's crew. Curran became a leader of the 10-week strike, eventually forming a supportive association known as the Seamen's Defense Committee.

Formation of NMU

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

and Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a partially landlocked ocean basin largely surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. In...

. In October 1936, Curran called a second strike, in part to improve working conditions and in part to embarrass the ISU. The four-month strike idled 50,000 seamen and 300 ships.

Curran, believing it was time to abandon the conservation International Seamen's Union, began to sign up members for a new, rival union. The level of organizing was so intense that hundreds of ships delayed their sailing time as seamen listened to organizers and signed union cards.

In May 1937, Curran and other leaders of his nascent movement formed the National Maritime Union. The Seamen's Defense Committee reconstituted itself as a union. It held its first convention in July, and 30,000 seamen switched their membership from the ISU to the NMU. Curran was elected president of the new organization. Elected secretary-treasurer of the union was Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

n-born Ferdinand Smith. Thus, from its inception NMU was racially integrated. Within six years, nearly all racial discrimination was eliminated in hiring, wages, living accommodations and work assignments.

A hallmark of the new union was the formation of hiring halls in each port. The hiring halls ensured a steady supply of experienced seamen for passenger and cargo ships, and reduced the corruption which plagued the hiring of able seamen. The hiring halls also worked to combat racial discrimination and promote racial harmony among maritime workers.

Within a year, the NMU had more than 50,000 members, and most American shippers were under contract. Stripped of most of its membership, the ISU became almost moribund.

In July 1937, Curran and other seamen's union leaders were invited by John L. Lewis

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America from 1920 to 1960...

to come to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, to form a major organizing drive among ship and port workers. The unions comprising the CIO had been ejected by the American Federation of Labor

American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor was one of the first federations of labor unions in the United States. It was founded in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions disaffected from the Knights of Labor, a national labor association. Samuel Gompers was elected president of the Federation at its...

(AFL) in November 1936, and now Lewis wanted to launch a maritime union. His goal was to create, out of the 300,000 maritime industry's workers, a union as large and influential as the Steel Workers Organizing Committee

Steel Workers Organizing Committee

The Steel Workers Organizing Committee was one of two precursor labor organizations to the United Steelworkers. It was formed by the CIO in 1936. It disbanded in 1942 to become the United Steel Workers of America....

. Although Lewis favored Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges was an Australian-American union leader, in the International Longshore and Warehouse Union , a longshore and warehouse workers' union on the West Coast, Hawaii and Alaska which he helped form and led for over 40 years...

, president of the Pacific Coast District of the International Longshoremen's Association

International Longshoremen's Association

The International Longshoremen's Association is a labor union representing longshore workers along the East Coast of the United States and Canada, the Gulf Coast, the Great Lakes, Puerto Rico, and inland waterways...

, to lead the new maritime industrial union, the other union leaders balked. Curran agreed to affiliate with the CIO, but refused to let Bridges or anyone else take over his union. His views were reflected among those of the other union leaders, and the CIO's maritime industrial union never got off the ground.

Presidency

During the next 36 years, Joseph Curran worked to make American merchant seamen the best-paid maritime workers in the world. NMU established a 40-hour work week, overtime, paid vacations, pension and health benefits, tuition reimbursement, and standards for shipboard food and living quarters. Curran even built a union-run school to retrain union members, and won large employer donations through collective bargaining to build the school.Curran was a vociferous advocate of maritime workers' rights. When Joseph P. Kennedy advocated legislation to outlaw maritime strikes and make arbitration of labor disputes compulsory, Curran called him a "union wrecker". When Kennedy was under consideration as executive director of the United Seamen's Service (an association which assists, feeds and houses American merchant seamen overseas), Curran successfully opposed the multi-millionaire's candidacy. Curran put such pressure on Kennedy that on February 18, 1938, Kennedy resigned as chair of the United States Maritime Commission

United States Maritime Commission

The United States Maritime Commission was an independent executive agency of the U.S. federal government that was created by the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, passed by Congress on June 29, 1936, and replaced the U.S. Shipping Board which had existed since World War I...

.

Curran was also a strong supporter of far-left-wing causes. In August 1940, he urged unions in the New York City area to support an "emergency peace mobilization" opposing U.S. entry into the war in Europe.

In 1940, Curran was elected a vice president of the CIO. When the CIO and AFL merged in 1955, he was appointed a vice president of the merged organization as well.

Greater New York Industrial Union

Curran was also elected president of the Greater New York Industrial Union.The Greater New York Industrial Union (GNYIU) was organized by the CIO in 1940 as a central labor body for New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. CIO-affiliated local unions in New York City and the nearby vicinity were its primary members. At the organization's founding convention on July 24, 1940, Curran was elected president of GNYIU. Saul Kills, a member of the American Newspaper Guild, was elected its secretary-treasurer. The organization had 250 local union affiliates, representing more than 500,000 workers.

By 1948, however, there were serious concerns about communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

infiltration of the GNYIU. The United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

appointed a special investigative subcommittee to look into the matter. Several CIO unions were investigated, including the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America

United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America

The United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America , is an independent democratic rank-and-file labor union representing workers in both the private and public sectors across the United States....

, the Teachers Union of the City of New York, the United Public Workers of America

United Public Workers of America

The United Public Workers of America was an American labor union representing federal, state, county, and local government employees which existed from 1946 to 1952. The union challenged the constitutionality of the Hatch Act of 1939, which prohibited federal executive branch employees from...

and the Department Store Employees Union

Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union

Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union is a labor union in the United States and Canada that is a semi-autonomous division of the United Food and Commercial Workers, Change to Win Federation...

.

CIO president Philip Murray

Philip Murray

Philip Murray was a Scottish born steelworker and an American labor leader. He was the first president of the Steel Workers Organizing Committee , the first president of the United Steelworkers of America , and the longest-serving president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations .-Early...

appointed a three-member board in October 1940 to forestall the House investigation. The board members reported to Murray that Curran, Kills and the GNYIU executive board had been advocating pro-communist policies. The GNYIU was on the verge of supporting Henry A. Wallace

Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace was the 33rd Vice President of the United States , the Secretary of Agriculture , and the Secretary of Commerce . In the 1948 presidential election, Wallace was the nominee of the Progressive Party.-Early life:Henry A...

in an independent bid for president as well. The national CIO executive board revoked the charter of the GNYIU in November 1940. Curran denied that he was a communist before both the CIO executive board and the Joint Commerce Committee of the U.S. Congress. Curran became increasingly anti-communist thereafter. In 1946, he pulled the NMU out of a Committee for Maritime Unity which was led by Harry Bridges. After World War II, he purged thousands of members and elected leaders he suspected of harboring communist sympathies.

Other roles

Curran served on a number of other committees, boards and positions with other organizations.For many years, he was chair of the AFL-CIO

AFL-CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, commonly AFL–CIO, is a national trade union center, the largest federation of unions in the United States, made up of 56 national and international unions, together representing more than 11 million workers...

's Maritime Committee. He was also co-chair of the Labor-Management Maritime Committee, a body established by AFL-CIO maritime unions and U.S. shipping companies to discuss and resolve labor issues.

Curran was also vice chairman of the Seafarer's Section of the International Transportworkers Federation, an international confederation of maritime unions.

Curran was also vice president of the United Seamen's Service.

Retirement and death

Curran suffered a heart attack in 1953 which left him somewhat less physically able than before. Over the next few years, he gradually cut back his workload, and stopped visiting local unions and attending most union meetings. In the mid-1960s, he turned over most of the union's daily business to secretary-treasurer Shannon J. WallShannon J. Wall

Shannon J. Wall was a merchant seaman and an American labor leader. He was president of the National Maritime Union from 1973 to 1990...

.

By the mid-1960s, Curran was being criticized for ignoring his members' needs and concerns. His $85,000-a-year salary was one of the highest in the American labor movement even though his union was small and shedding members. He enjoyed an unlimited expense account, and traveled by chartered jet and private limousine. He cajoled the union's executive board into building a massive, Art Deco

Art Deco

Art deco , or deco, is an eclectic artistic and design style that began in Paris in the 1920s and flourished internationally throughout the 1930s, into the World War II era. The style influenced all areas of design, including architecture and interior design, industrial design, fashion and...

headquarters in Manhattan, and had the edifice named after himself.

In 1966, with the surreptitious help of NMU staffers, union member James B. Morrissey challenged the results of Curran's 1966 re-election as fraudulent. The Department of Labor agreed, but a re-run election did not change the outcome.

In 1973, shortly after Curran won re-election for a thirteenth term as union president, Morrissey sued Curran and charged him with misappropriating union funds. In a precedent-setting ruling in Morrissey and Ibrahim v. Curran, 650 F.2d 1267

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1981), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit established a broad right for union members to sue union officers for improper financial practices.

Morrissey's barrage of lawsuits against Curran led Curran to retire suddenly on March 5, 1973. Long-time secretary-treasurer Shannon J. Wall

Shannon J. Wall

Shannon J. Wall was a merchant seaman and an American labor leader. He was president of the National Maritime Union from 1973 to 1990...

succeeded him as president.

Curran retired to Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, USA, incorporated in May 1925. In the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 74,764; the 2006 population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 86,396. However, the majority of the people under the postal address of Boca Raton, about...

. He died there of cancer on August 14, 1981.

Family

Curran married Retta Toble, a former cruise ship waitress, in 1939. The couple had a son, Joseph Paul Curran, Jr. Retta Curran died in 1963. In 1965, Curran married Florence Stetler.External links

- Image of the National Maritime Union, Joseph Curran Annex.

- Reminiscences of Joseph Curran. Individual Interview List Oral History Project. Oral History Research Office. Columbia University. 1964.

- Scrapbook, 1940-1948. Greater New York State Industrial Union Council. Congress of Industrial Organizations. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library.

- Seafarers International Union of North America Web site

- 1948 article and Cover Illustration from Time Magazine