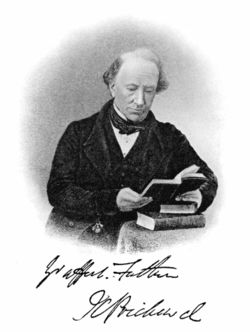

James Cowles Prichard

Encyclopedia

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

FRS (11 February 1786, Ross-on-Wye

Ross-on-Wye

Ross-on-Wye is a small market town with a population of 10,089 in southeastern Herefordshire, England, located on the River Wye, and on the northern edge of the Forest of Dean.-History:...

, Herefordshire

Herefordshire

Herefordshire is a historic and ceremonial county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire" NUTS 2 region. It also forms a unitary district known as the...

– 23 December 1848) was an English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

physician

Physician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

and ethnologist. His influential Researches into the physical history of mankind touched upon the subject of evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

. He was also the first person to name senile dementia.

Life

His parents were QuakersReligious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

: his mother Welsh, and his father of an English family who had emigrated to Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

. Within a few years of his birth in Ross, Prichard's parents moved to Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, where his father now worked in the Quaker ironworks

Ironworks

An ironworks or iron works is a building or site where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and/or steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e...

of Harford, Partridge and Cowles. Upon his father's retirement in 1800 he returned to Ross. As a child Prichard was educated mainly at home by tutors and his father, in a range of subjects, including modern languages and general literature.

Rejecting his father's wish that he should join the ironworks, Prichard decided upon a medical career. Here he faced the difficulty that as a Quaker he could not become a member of the Royal College of Physicians

Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London was founded in 1518 as the College of Physicians by royal charter of King Henry VIII in 1518 - the first medical institution in England to receive a royal charter...

. Therefore he started on apprenticeships that led to the ranks of apothcaries and surgeons. The first step was to study under the Quaker obstetrician Dr Thomas Pole

Thomas Pole

-Life:He was born on 13 October 1753 in Philadelphia, the youngest son of John Pole , a native of Wiveliscombe, Somerset, who emigrated to New Jersey. His mother's maiden name was Rachel Smith, of Burlington. Thomas was brought up as a member of the Society of Friends...

of Bristol. Apprenticeships followed to other Quaker physicians, and to St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS hospital in London, England. It is administratively a part of Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust. It has provided health care freely or under charitable auspices since the 12th century and was originally located in Southwark.St Thomas' Hospital is accessible...

in London. Eventually, in 1805, he took the plunge: he entered medical school at Edinburgh University, where his religious affiliation was no bar. Also, Scottish universities were in esteem, having contributed greatly to the Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

of the previous century.

He took his M.D.

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

at Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

, his doctoral thesis of 1808 being his first attempt at the great question of his life: the origin of human varieties and races. Later, he read for a year at Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

, after which came a significant personal event: he left the Society of Friends to join the established Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. He next moved to St John's College, Oxford

St John's College, Oxford

__FORCETOC__St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, one of the larger Oxford colleges with approximately 390 undergraduates, 200 postgraduates and over 100 academic staff. It was founded by Sir Thomas White, a merchant, in 1555, whose heart is buried in the chapel of...

, afterwards entering as a gentleman commoner at Trinity College, Oxford

Trinity College, Oxford

The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the foundation of Sir Thomas Pope , or Trinity College for short, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It stands on Broad Street, next door to Balliol College and Blackwells bookshop,...

, but taking no degree in either university.

In 1810 Prichard settled at Bristol as a physician, eventually attaining an established position at the Bristol Infirmary

Bristol Royal Infirmary

The Bristol Royal Infirmary, also known as the BRI, is a large teaching hospital situated in the centre of Bristol, England. It has links with the medical faculty of the nearby University of Bristol, and the Faculty of Health and Social Care at the University of the West of England, also in...

in 1816.

In 1845 he was made a Commissioner in Lunacy

Lunacy

Lunacy may refer to:* Lunacy, the condition suffered by a lunatic, now used only informally* Lunacy , a 2005 Jan Švankmajer's film* Lunacy , a video game for Sega Saturn* Luna Sea, a Japanese rock band originally named Lunacy...

, and moved to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. He died there three years later of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disease that occurs following a Streptococcus pyogenes infection, such as strep throat or scarlet fever. Believed to be caused by antibody cross-reactivity that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain, the illness typically develops two to three weeks after...

. At the time of his death he was president of the Ethnological Society

Ethnological Society of London

The Ethnological Society of London was founded in 1843 by a breakaway faction of the Aborigines' Protection Society . It quickly became one of England's leading scientific societies, and a meeting-place not only for students of ethnology but also for archaeologists interested in prehistoric...

and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Works

In 1813 he published his Researches into the Physical History of Man, in 2 vols, on essentially the same themes as his dissertation in 1808. The book grew until the 3rd ed of 1836-47 occupied five volumes. The central conclusion of the work is the primitive unity of the human species, acted upon by causes which have since divided it into permanent varieties or races. The work is dedicated to BlumenbachJohann Friedrich Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach was a German physician, physiologist and anthropologist, one of the first to explore the study of mankind as an aspect of natural history, whose teachings in comparative anatomy were applied to classification of what he called human races, of which he determined...

, whose five races of man are adopted. But where Prichard excelled Blumenbach and all his other predecessors was in his grasp of the principle that people should be studied by combining all available characters.

Evolution

Three British men, all medically qualified and publishing between 1813 and 1819, William Lawrence, William Charles WellsWilliam Charles Wells

William Charles Wells MD FRS FRSEd , was a Scottish-American physician and printer. He lived a life of extraordinary variety, did some notable medical research, and made the first clear statement about natural selection. He applied the idea to the origin of different skin colours in human races,...

and Prichard, addressed issues relevant to human evolution. All tackled the question of variation and race in humans; all agreed that these differences were heritable, but only Wells approached the idea of natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

as a cause. Prichard, however, indicates Africa (indirectly) as the place of human origin, in this summary passage:

- "On the whole there are many reasons which lead us to the conclusion that the primitive stock of men were probably Negroes, and I know of no argument to be set on the other side."

This striking opinion was omitted in later editions, for reasons which are unclear. As a consequence of this and other changes, Prichard's book was at its best (so far as this point goes) in its shorter first edition. However, others have identified the second edition as the best for its evolutionary ideas.

Anthropology

In 1843 Prichard published his Natural History of Man, in which he reiterated his belief in the specific unity of man, pointing out that the same inward and mental nature can be recognized in all the races. Prichard was an early member of the Aboriginal Protection Society, which influenced the 1869 Aboriginal Protection ActAboriginal Protection Act

The Aboriginal Protection Act, enacted in 1869 by the colony of Victoria, Australia gave extensive powers over the lives of Aboriginal people to the government's Board for the Protection of Aborigines, including regulation of residence, employment and marriage....

.

Prichard was influential in ethnology

Ethnology

Ethnology is the branch of anthropology that compares and analyzes the origins, distribution, technology, religion, language, and social structure of the ethnic, racial, and/or national divisions of humanity.-Scientific discipline:Compared to ethnography, the study of single groups through direct...

and anthropology

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

. He stated that the Celtic languages

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

are allied by language with the Slavonian, German and Pelasgian (Greek and Latin), thus forming a fourth European branch of Indo-European languages

Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred related languages and dialects, including most major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and South Asia and also historically predominant in Anatolia...

. His treatise containing Celtic compared with Sanskrit

Sanskrit

Sanskrit , is a historical Indo-Aryan language and the primary liturgical language of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism.Buddhism: besides Pali, see Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Today, it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand...

words appeared in 1831 under the title Eastern Origin of the Celtic nations. An essay by Adolphe Pictet

Adolphe Pictet

Adolphe Pictet was a Swiss linguist, born in Geneva.Pictet is well-known for his research in the field of comparative linguistics. He was the cousin of the biologist Francois Jules Pictet.-Works:...

, which made its author's reputation, was published independently of the earlier investigations of Prichard.

Psychiatry

In medicine, he specialised in what is now psychiatryPsychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study and treatment of mental disorders. These mental disorders include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities...

. In 1822 he published A treatise on diseases of the nervous system (pt. I), and in 1835 a Treatise on insanity and other disorders affecting the mind, in which he advanced the theory of the existence of a distinct mental illness

Mental illness

A mental disorder or mental illness is a psychological or behavioral pattern generally associated with subjective distress or disability that occurs in an individual, and which is not a part of normal development or culture. Such a disorder may consist of a combination of affective, behavioural,...

called moral insanity

Moral insanity

Moral insanity is a medical diagnosis first described by the French humanitarian and psychiatrist Philippe Pinel in 1806...

. Prichard's work was also the first definition of senile dementia in the English language. In 1842, following up on moral insanity, he published On the different forms of insanity in relation to jurisprudence] designed for the use of persons concerned in legal questions regarding unsoundness of mind.

Other works

Among his other works were:- A review of the doctrine of a vital principle (1829)

- On the treatment of hemiplegia (1831)

- On the extinction of some varieties of the human race (1839)

- Analysis of Egyptian mythology (1819).