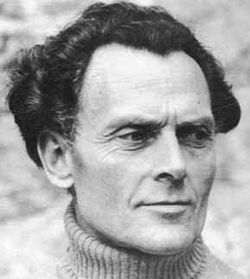

Ian Anstruther

Encyclopedia

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

twice over. He inherited substantial property interests in South Kensington

South Kensington

South Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London. It is a built-up area located 2.4 miles west south-west of Charing Cross....

, and wrote several books on specialised areas of 19th-century social and literary history.

Early life

Anstruther was born in BuckinghamshireBuckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

, the younger son of Douglas Tollemache Anstruther and his first wife, Enid (née Campbell). His father was the son of MP Harry Anstruther, himself a younger son of MP Lieutenant Colonel Sir Robert Anstruther, 5th Baronet

Sir Robert Anstruther, 5th Baronet

Sir Robert Anstruther, 5th Baronet was a Scottish Liberal Party politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1864 and 1886....

. His maternal grandfather was Lord George Campbell, younger son of the 8th Duke of Argyll.

His father served in the Army and then worked for the London and South Western Railway

London and South Western Railway

The London and South Western Railway was a railway company in England from 1838 to 1922. Its network extended from London to Plymouth via Salisbury and Exeter, with branches to Ilfracombe and Padstow and via Southampton to Bournemouth and Weymouth. It also had many routes connecting towns in...

. His parents spent 14 years in divorce

Divorce

Divorce is the final termination of a marital union, canceling the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage and dissolving the bonds of matrimony between the parties...

and then custody proceedings from 1924, and so he spent much of his youth with his mother's sister, Joan Campbell, at Strachur House in Argyllshire and her London house in Bryanston Square

Bryanston Square

Bryanston Square is a square in Marylebone, Westminster, London, England. Named after its owner Henry William Portman's home village of Bryanston in Dorset, it was built as part of the Portman Estate between 1810 and 1815, along with Montagu Square a little to the east and Wyndham Place to its...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. His father's sister, aunt Joyce, better known as Jan Struther

Jan Struther

Jan Struther was the pen name of Joyce Anstruther, later Joyce Maxtone Graham and finally Joyce Placzek , an English writer remembered for her character Mrs...

, created Mrs. Miniver

Mrs. Miniver

Mrs. Miniver is a fictional character created by Jan Struther in 1937 for a series of newspaper columns for The Times, later adapted into a movie of the same name.-Origin:...

.

Education and military career

He was educated at EtonEton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, and joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 5th Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland....

in 1939 when the Second World War broke out. An amateur radio ham, he was quickly transferred to the Royal Corps of Signals

Royal Corps of Signals

The Royal Corps of Signals is one of the combat support arms of the British Army...

, and was commissioned, ending up as a Captain. He read Natural Sciences at New College, Oxford

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

from 1940 to 1942, before returning to Catterick

Catterick Garrison

Catterick Garrison is a major Army base located in Northern England. It is the largest British Army garrison in the world with a population of around 12,000, plus a large temporary population of soldiers, and is larger than its older neighbour...

to train for the invasion of France. He landed with his brigade in Normandy

Normandy

Normandy is a geographical region corresponding to the former Duchy of Normandy. It is in France.The continental territory covers 30,627 km² and forms the preponderant part of Normandy and roughly 5% of the territory of France. It is divided for administrative purposes into two régions:...

three weeks after D-Day

D-Day

D-Day is a term often used in military parlance to denote the day on which a combat attack or operation is to be initiated. "D-Day" often represents a variable, designating the day upon which some significant event will occur or has occurred; see Military designation of days and hours for similar...

, and took charge of a team of signallers.

After the war, he chanced to meet Sir Archibald Clerk Kerr, a family friend, on a bus in London. Kerr (later 1st Baron Inverchapel) had been ambassador in Moscow during the war, and had just been appointed British ambassador to the United States; he asked Anstruther to become his private secretary. Anstruther readily agreed, and spent four years in America in the Diplomatic Service

Diplomatic service

Diplomatic service is the body of diplomats and foreign policy officers maintained by the government of a country to communicate with the governments of other countries. Diplomatic personnel enjoy diplomatic immunity when they are accredited to other countries...

. He moved to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

in 1951, to advance his ambition to become a writer. He met Honor Blake, and they were married on 7 March 1951. They had one daughter. They were divorced in 1963, and he married architect Susan Walker (née Paten) on 15 November 1963. They had two sons and three daughters.

He was surprised to inherit an estate in South Kensington (including Thurloe Square

Thurloe Square

Thurloe Square is a traditional garden square in South Kensington, London, England.There are private communal gardens in the centre of the square for use by the local residents. The Victoria and Albert Museum is close by to the north across Thurloe Place and Cromwell Gardens...

and Alexander Square) from his aunt Joan in 1960, making him wealthy. He had bought a country estate at Barlavington

Barlavington

Barlavington is a small village and civil parish in the Chichester district of West Sussex, England. The village is situated about six kilometres south of Petworth, east of the A285 road....

, on the north of the South Downs

South Downs

The South Downs is a range of chalk hills that extends for about across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen Valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, near Eastbourne, East Sussex, in the east. It is bounded on its northern side by a steep escarpment, from whose...

near Petworth

Petworth

Petworth is a small town and civil parish in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England. It is located at the junction of the A272 east-west road from Heathfield to Winchester and the A283 Milford to Shoreham-by-Sea road. Some twelve miles to the south west of Petworth along the A285 road...

in West Sussex

West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in the south of England, bordering onto East Sussex , Hampshire and Surrey. The county of Sussex has been divided into East and West since the 12th century, and obtained separate county councils in 1888, but it remained a single ceremonial county until 1974 and the coming...

, in 1956, including 3000 acres (12.1 km²) of woodland, farmland and downland. He also bought a house near St. Tropez in 1973.

As a writer

He wrote 8 books, including I Presume (1956), a biography of journalist H.M. Stanley; an account of the Eglinton tournament entitled The Knight and the Umbrella (1963); The Scandal of the Andover Workhouse (1973), exploring the iniquities of the workhouseWorkhouse

In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a spike, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment...

system; a biography of Oscar Browning

Oscar Browning

Oscar Browning was an English writer, historian, and educational reformer. His greatest achievement was the cofounding, along with Henry Sidgwick, of the Cambridge University Day Training College in 1891...

(1983), Coventry Patmore's Angel (1992), on Coventry Patmore

Coventry Patmore

Coventry Kersey Dighton Patmore was an English poet and critic best known for The Angel in the House, his narrative poem about an ideal happy marriage.-Youth:...

and his wife Emily, and his poem The Angel in the House

The Angel in the House

The Angel in the House is a narrative poem by Coventry Patmore, first published in 1854 and expanded up until 1862. Although largely ignored upon publication, it became enormously popular during the later nineteenth century and its influence continued well into the twentieth...

; and a book about Sir Richard Broun, The Baronets' Champion (2006). He also wrote about Frederic William Farrar

Frederic William Farrar

Frederic William Farrar was a cleric of the Church of England .Farrar was born in Bombay, India and educated at King William's College on the Isle of Man, King's College London and Trinity College, Cambridge. At Cambridge he won the Chancellor's Gold Medal for poetry in 1852...

and his novel Eric, or, Little by Little

Eric, or, little by little

Eric, or, Little by Little is the title of a book by Frederic W. Farrar, first edition 1858. It was published by Adam & Charles Black, Edinburgh and London.The book deals with the descent into moral turpitude of a boy at a boarding school.The reads:...

.

He undertook much of his research in the London Library

London Library

The London Library is the world's largest independent lending library, and the UK's leading literary institution. It is located in the City of Westminster, London, England, United Kingdom....

in St James's Square. He donated funding in 1992 to enable it to build a new wing, which was named the Anstruther Wing. He was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries

Society of Antiquaries of London

The Society of Antiquaries of London is a learned society "charged by its Royal Charter of 1751 with 'the encouragement, advancement and furtherance of the study and knowledge of the antiquities and history of this and other countries'." It is based at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London , and is...

, and a member of the Royal Company of Archers

Royal Company of Archers

The Royal Company of Archers is a ceremonial unit that serves as the Sovereign's Bodyguard in Scotland, a role it has performed since 1822 and the reign of King George IV, when the company provided a personal bodyguard to the King on his visit to Scotland. It is currently known as the Queen's...

.

Personal life

He enjoyed cars, owning an Aston Martin DB6Aston Martin DB6

The Aston Martin DB6 is a grand tourer made by British car manufacturer Aston Martin. Produced from September 1965 to January 1971, the DB6 had the longest production run up to that date of any Aston Martin model...

, a Maserati

Maserati

Maserati is an Italian luxury car manufacturer established on December 1, 1914, in Bologna. The company's headquarters is now in Modena, and its emblem is a trident. It has been owned by the Italian car giant Fiat S.p.A. since 1993...

, and several Porsche

Porsche

Porsche Automobil Holding SE, usually shortened to Porsche SE a Societas Europaea or European Public Company, is a German based holding company with investments in the automotive industry....

s, but disliked excessive speed, and was occasionally stopped by the police for driving too slowly. He later traded down to a smart

Smart (automobile)

Smart is an automotive branch of Daimler AG. Smart is a German manufacturer of microcars produced in Hambach, France, and Böblingen, Germany...

car.

He succeeded his cousin Sir Ralph Anstruther, 7th Baronet

Sir Ralph Anstruther, 7th Baronet

Sir Ralph Anstruther, 7th Baronet, GCVO, MC, DL was a Scottish courtier.The only son of Captain Robert Edward Anstruther MC of the Black Watch only son of Sir Ralph William Anstruther, 6th Baronet, and Marguerite Blanche Lily de Burgh, he was educated at Eton and at Magdalene College,...

in 2002, inheriting two Anstruther Baronetcies

Anstruther Baronets

There have been three Anstruther Baronetcies — two in the Baronetage of Nova Scotia and one in the Baronetage of Great Britain . There is also an Anstruther-Gough-Calthorpe baronetcy in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom...

- of Nova Scotia, of Balcaskie (1694) and of Anstruther (1700). His cousin had been hereditary Carver

Master Carver

The Master Carver is a member of the Royal household in Scotland. A Crown Charter of 1704 ratified by Parliament in 1705, erected Sir William Anstruther's land into the Barony of Anstruther and conferred upon him the heritable offices of Master Carver and one of the Masters of the Household...

to the Sovereign in Scotland, but the office passed instead to his second son, Toby. He also believed (almost certainly incorrectly) that he held the British baronetcy of Anstruther (1798), but its remainder (to "heirs-male of the body legitimately begotten" of the grantee) would have made it extinct on the death of Sir Windham Carmichael-Anstruther, 11th Baronet, in 1980 as most reference books, such as Burke and Debrett, have noted.

As an adult, he adhered to a fixed routine. He habitually wore a bow tie

Bow tie

The bow tie is a type of men's necktie. It consists of a ribbon of fabric tied around the collar in a symmetrical manner such that the two opposite ends form loops. Ready-tied bow ties are available, in which the distinctive bow is sewn into shape and the band around the neck incorporates a clip....

in the day, and a cravat

Cravat

The cravat is a neckband, the forerunner of the modern tailored necktie and bow tie, originating from 17th-century Croatia.From the end of the 16th century, the term band applied to any long-strip neckcloth that was not a ruff...

in the evening. He walked each day in the South Downs

South Downs

The South Downs is a range of chalk hills that extends for about across the south-eastern coastal counties of England from the Itchen Valley of Hampshire in the west to Beachy Head, near Eastbourne, East Sussex, in the east. It is bounded on its northern side by a steep escarpment, from whose...

, lunching at one of five village pubs during the week, always drinking ginger beer

Ginger beer

Ginger beer is a carbonated drink that is flavored primarily with ginger and sweetened with sugar or artificial sweeteners.-History:Brewed ginger beer originated in England in the mid-18th century and became popular in Britain, the United States, and Canada, reaching a peak of popularity in the...

. He took tea

Tea

Tea is an aromatic beverage prepared by adding cured leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant to hot water. The term also refers to the plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely consumed beverage in the world...

at 5pm, and ate supper

Supper

Supper is the name for the evening meal in some dialects of English - ordinarily the last meal of the day. Originally, in the Middle Ages, it referred to the lighter meal following dinner, where until the 18th century dinner was invariably eaten as the midday meal.The term is derived from the...

8.30pm. He always dressed for dinner in a velvet suit and silk cravat, before his two Martini

Martini

Martini may refer to:* Martini , a popular cocktail* Martini , a brand of vermouth* Martini , a Swiss automobile company* Martini , a French manufacturer of racing cars...

s. His family knew that matters were serious when he failed to dress for dinner a few weeks before his death.

He died at Barlavington. He was survived by his daughter from his first marriage, and two sons and three daughters from his second marriage. Due to differences between English law and Scottish law, one son, Sebastian (born prior to his parents' marriage), inherited the Scottish title, becoming 9th Baronet of Balcaskie and 11th Baronet of Anstruther (both being Nova Scotia or Scottish Baronetages). Obituaries to Sir Ian noted, erroneously that the Great Britain Baronetcy of Anstruther (1798) had passed to his other son Toby (born after Sir Ian's second marriage). He left an estate valued in excess of £35,000,000.