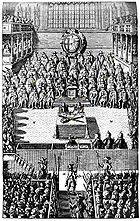

High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I

Encyclopedia

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

to try King Charles I of England

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

. This was an ad hoc tribunal created specifically for the purpose of trying the king, although the same name was used again for subsequent courts.

Neither the involvement of Parliament in ending a reign, nor the idea of trying a monarch was entirely novel. Although Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

had been overthrown and killed by his successor, Parliament had asked for the abdication of Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

who was charged with incompetence. Parliament also accepted the resignation of Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

. However, in both these cases, Parliament acted at the behest of the new monarch. In the case of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey , also known as The Nine Days' Queen, was an English noblewoman who was de facto monarch of England from 10 July until 19 July 1553 and was subsequently executed...

, Parliament rescinded her proclamation as queen. She was subsequently charged with and tried for high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

, but she was not brought to trial while still a reigning monarch.

Background

After the first English Civil WarEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, the parliamentarians accepted the premise that the King, although wrong, had been able to justify his fight, and that he would still be entitled to limited powers as King under a new constitutional settlement. By provoking the second Civil War even while defeated and in captivity, Charles was responsible for unjustifiable bloodshed. The secret "Engagement"

Engagers

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamenterians after his defeat in the First Civil War....

treaty with the Scots was considered particularly unpardonable; "a more prodigious treason," said Cromwell, "than any that had been perfected before; because the former quarrel was that Englishmen might rule over one another; this to vassalize us to a foreign nation." Cromwell up to this point had supported negotiations with the king but now rejected further negotiations.

In making war against Parliament, the king had caused the deaths of thousands. Estimated deaths from the first two English civil wars has been reported as 84,830 killed with estimates of another 100,000 dying from war-related disease." In 1650, the time, the population of England was only 5.1 million, so the war casualties totalled an astonishing 3.6 percent of the population, almost double the proportional deaths of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

Following the second civil war

Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War was the second of three wars known as the English Civil War which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War and the...

, the army and the Independent

Independent (religion)

In English church history, Independents advocated local congregational control of religious and church matters, without any wider geographical hierarchy, either ecclesiastical or political...

s in Parliament were determined that the King should be punished, but they did not command a majority. Parliament debated whether to return the King to power and those who still supported Charles's place on the throne, mainly Presbyterians, tried once more to negotiate with him.

Furious that Parliament continued to countenance Charles as King, the army marched on Parliament and purged the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

in an act later known as "Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge

Pride’s Purge is an event in December 1648, during the Second English Civil War, when troops under the command of Colonel Thomas Pride forcibly removed from the Long Parliament all those who were not supporters of the Grandees in the New Model Army and the Independents...

" after the commanding officer of the operation. On Wednesday, 6 December 1648, Colonel Thomas Pride

Thomas Pride

Thomas Pride was a parliamentarian general in the English Civil War, and best known as the instigator of "Pride's Purge".-Early Life and Starting Career:...

's Regiment of Foot took up position on the stairs leading to the House, while Nathaniel Rich’s Regiment of Horse provided backup. Pride himself stood at the top of the stairs. As Members of Parliament (MPs) arrived, he checked them against the list provided to him. Troops arrested 45 MPs and kept 146 out of parliament.

Only 75 were allowed in, and then only at the army's bidding. On 13 December, the "Rump Parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

", as the purged House of Commons came to be known, broke off negotiations with the King. Two days later, the Council of Officers of the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

voted that the King be moved to Windsor

Windsor, Berkshire

Windsor is an affluent suburban town and unparished area in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is widely known as the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the British Royal Family....

"in order to the bringing of him speedily to justice". In the middle of December, the King was moved from Windsor to London.

Establishing the court

After the King had been moved to London, the Rump Parliament passed a Bill setting up what was described as a High Court of Justice in order to try Charles I for high treasonHigh treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

in the name of the people of England. The bill initially nominated 3 judges and 150 commissioners, but following opposition in the House of Lords, the judges and members of the Lords were removed. When the trial began, there were 135 commissioners who were empowered to try the King although only 68 would ever sit in judgement. The Solicitor General

Solicitor General for England and Wales

Her Majesty's Solicitor General for England and Wales, often known as the Solicitor General, is one of the Law Officers of the Crown, and the deputy of the Attorney General, whose duty is to advise the Crown and Cabinet on the law...

John Cooke was appointed prosecutor.

Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of England. The charge against Charles I stated that the king, "for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented...", that the "wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation." The indictment held him "guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby."

Although the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

refused to pass the bill and the Royal Assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

naturally was lacking, the Rump Parliament referred to the ordinance as an "Act" and pressed on with the trial anyway. The intention to place the King on trial was re-affirmed on 6 January by a vote of 29 to 26 with An Act of the Commons Assembled in Parliament. At the same time, the number of commissioners was reduced to 135 – any twenty of whom would form a quorum

Quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly necessary to conduct the business of that group...

– when the judges, members of the House of Lords and others who might be sympathetic to the King were removed.

The commissioners met to make arrangements for the trial on 8 January when well under half were present - a pattern that was to be repeated at subsequent sessions. On 10 January, John Bradshaw

John Bradshaw (judge)

John Bradshaw was an English judge. He is most notable for his role as President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I and as the first Lord President of the Council of State of the English Commonwealth....

was chosen as President of the Court. During the following ten days, arrangements for the trial were completed; the charges were finalised and the evidence to be presented was collected.

Trial

The trial began on 20 January 1649 in Westminster Hall, with a moment of high drama. After the proceedings were declared open, Solicitor General John Cooke rose to announce the indictmentIndictment

An indictment , in the common-law legal system, is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that maintain the concept of felonies, the serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that lack the concept of felonies often use that of an indictable offence—an...

; standing immediately to the right of the King, he began to speak, but he had uttered only a few words when Charles attempted to stop him by tapping him sharply on the shoulder with his cane and ordering him to "Hold". Cooke ignored this and continued, so Charles poked him a second time and rose to speak; despite this, Cooke continued. At this point Charles, incensed at being thus ignored, struck Cooke across the shoulder so forcefully that the ornate silver tip of the cane broke off, rolled down Cooke's gown and clattered onto the floor between them. Charles then ordered Cooke to pick it up, but Cooke again ignored him, and after a long pause, Charles stooped to retrieve it.

When given the opportunity to speak, Charles refused to enter a plea, claiming that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch. He believed that his own authority to rule had been given to him by God and by the traditions and laws of England when he was crowned and anointed, and that the power wielded by those trying him was simply that of force of arms. Charles insisted that the trial was illegal, explaining, "No learned lawyer will affirm that an impeachment can lie against the King... one of their maxims is, that the King can do no wrong." Charles asked "I would know by what power I am called hither. I would know by what authority, I mean lawful". Charles maintained that the House of Commons on its own could not try anybody, and so he refused to plead.

The court proceeded as if the king had pleaded guilty (pro confesso), as was the standard legal practice in case of a refusal to plead. However, witnesses were heard by the judges for 'the further and clearer satisfaction of their own judgement and consciences.'

Thirty witnesses were summoned, but some were later excused. The evidence was heard in the Painted Chamber

Painted Chamber

The Painted Chamber was part of the original Palace of Westminster. It was destroyed by fire in 1834.Because it was originally a royal residence, the Palace did not include any purpose-built chambers for the two Houses. Important state ceremonies, including the State Opening of Parliament, were...

rather than Westminster Hall. King Charles was not present to hear the evidence against him and he had no opportunity to question witnesses.

The King was declared guilty at a public session on Saturday 27 January 1649 and sentenced to death. To show their agreement with the sentence, all of the 67 Commissioners who were present rose to their feet. During the rest of that day and on the following day, signatures were collected for his death warrant. This was eventually signed by 59 of the Commissioners, including 2 who had not been present when the sentence was passed.

Execution

King Charles was beheaded in front of the Banqueting HouseBanqueting House

In Tudor and Early Stuart English architecture a banqueting house is a separate building reached through pleasure gardens from the main residence, whose use is purely for entertaining. It may be raised for additional air or a vista, and it may be richly decorated, but it contains no bedrooms or...

of the Palace of Whitehall

Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall was the main residence of the English monarchs in London from 1530 until 1698 when all except Inigo Jones's 1622 Banqueting House was destroyed by fire...

on 30 January 1649. He declared that he had desired the liberty and freedom of the people as much as any;

but I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consists in having government.... It is not their having a share in the government; that is nothing appertaining unto them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things.

Francis Allen arranged payments and prepared accounts for the execution event.

Aftermath

Following the execution of Charles I, there was further large-scale fighting in IrelandCromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

, Scotland and England, known collectively as the third civil war

Third English Civil War

The Third English Civil War was the last of the English Civil Wars , a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists....

. A year and a half after the execution, Prince Charles was proclaimed King Charles II by the Scots and he led an invasion of England where he was defeated at the Battle of Worcester

Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 at Worcester, England and was the final battle of the English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell and the Parliamentarians defeated the Royalist, predominantly Scottish, forces of King Charles II...

. This marked the end of the civil wars.

The High Court of Justice during the Interregnum

The name continued to be used during the interregnum. James Earl of CambridgeJames Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton

General Sir James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton KG was a Scottish nobleman and influential Civil war military leader.-Young Arran:...

was tried and executed on 9 March 1649 by the 'High Court of Justice'.

In subsequent years the High Court of Justice was reconstituted under the following Acts.

- March 1650 An Act for Establishing an High Court of Justice.

- August 1650 An Act giving further Power to the High Court of Justice

- December 1650 An Act for Establishing an High Court of Justice within the Counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Huntington, Cambridge, Lincoln, and the Counties of the Cities of Norwich and Lincoln, and within the Isle of Ely.

- November 1653 An Act For The Establishing An High Court of Justice.

On 30 June 1654, Peter Vowell

Peter Vowell

Peter Vowell was a schoolteacher executed as a Catholic and Royalist conspirator.In May 1654 Vowell, from Islington, was arrested for his part in a plot to assassinate Oliver Cromwell as the Lord Protector and his guard of thirty mounted troops, travelled to Hampton Court...

and John Gerard were tried for High Treason by the High Court of Justice sitting in Westminster Hall. They had planned to assassinate Oliver Cromwell and restore Charles II as king. The plotters were found guilty and executed.

The restoration and beyond

After the RestorationEnglish Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

in 1660, all who had been active in the court that had tried and sentenced Charles I were targets for the new King. Most of those that were still alive attempted to flee the country. With the exception of Richard Ingoldsby

Richard Ingoldsby

Colonel Sir Richard Ingoldsby was an English officer in the New Model Army during the English Civil War and a politician who sat in the House of Commons variously between 1647 and 1685...

, all those that were captured were executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.

The charges against the king were echoed in the American colonists

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

against George III a century later, that the king had been "trusted with a limited power to govern by and according to the laws of the land, and not otherwise; and by his trust, oath, and office, being obliged to use the power committed to him for the good and benefit of the people, and for the preservation of their rights and liberties; yet, nevertheless, out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people..."

Further reading

- Full text of the Ordinance that established the court

- Victor Louis Stater. The Political History of Tudor and Stuart England, p. 144 Charges against Charles I

- T. B Howell, T.B. A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason other crimes and misdemeanors from the earliest period until the year 1783 Volume 12 of 21 Charles I to Charles II: The Trial of Charles Stuart, King of England; Before the High court of Justice, for High Treason

- Text of the sentence

- House of Lords Record Office: The Death Warrant of King Charles I

- Full text of the Act abolishing the Office of King, 17 March, 1649

- Geoffrey Robertson, The Tyrannicide Brief (2005), Chatto & Windus