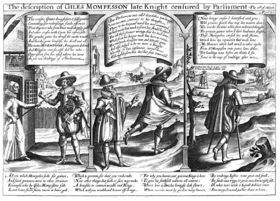

Giles Mompesson

Encyclopedia

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

malefactor and, officially, "notorious criminal" whose career was one based on speculation and graft

Political corruption

Political corruption is the use of legislated powers by government officials for illegitimate private gain. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is not considered political corruption. Neither are illegal acts by...

. He has come to be regarded as a synonym for graft and official corruption due to his use of nepotism

Nepotism

Nepotism is favoritism granted to relatives regardless of merit. The word nepotism is from the Latin word nepos, nepotis , from which modern Romanian nepot and Italian nipote, "nephew" or "grandchild" are also descended....

to gain positions of licensing businesses and pocketing the fees. In the reaction against Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, Mompesson's name was invoked as a symbol of all that was wrong with aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. Sir Giles Overreach, the anti-hero of Philip Massinger

Philip Massinger

Philip Massinger was an English dramatist. His finely plotted plays, including A New Way to Pay Old Debts, The City Madam and The Roman Actor, are noted for their satire and realism, and their political and social themes.-Early life:The son of Arthur Massinger or Messenger, he was baptized at St....

's 1625 play A New Way to Pay Old Debts

A New Way to Pay Old Debts

A New Way to Pay Old Debts is a play of English Renaissance drama, the most popular drama of Philip Massinger. Its central chararacter, Sir Giles Overreach, became one of the more popular villains on English and American stages through the 19th century.-Performance:Massinger most likely wrote the...

, is based on Mompesson. http://www.bartleby.com/81/7177.html

Licensing monopoly and graft

Mompesson was born in WiltshireWiltshire

Wiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

. He grew up into a small, swarthy individual with black hair. He entered Hart Hall, Oxford

Hertford College, Oxford

Hertford College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It is located in Catte Street, directly opposite the main entrance of the original Bodleian Library. As of 2006, the college had a financial endowment of £52m. There are 612 students , plus various visiting...

in 1600, but left without a degree the next year for Lincoln's Inn

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn. Although Lincoln's Inn is able to trace its official records beyond...

; he later departed there without becoming a lawyer. In 1606 or 1607, he married Katherine, the daughter of Sir John St. John, one of the most prominent men in Wiltshire. Through his father-in-law's influence, Mompesson became a Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

for Great Bedwyn

Great Bedwyn (UK Parliament constituency)

Great Bedwyn was a parliamentary borough in Wiltshire, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1295 until 1832, when the borough was abolished by the Great Reform Act.-1295–1640:-1640–1832:Notes...

in 1614. Another daughter of John St. John (and thus Mompesson's sister-in-law) married Edward Villiers

Edward Villiers

Sir Edward Villiers , the fourth son of Sir Edward Villiers and Barbara St. John, half-nephew to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham...

, the half-brother of George Villiers

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham KG was the favourite, claimed by some to be the lover, of King James I of England. Despite a very patchy political and military record, he remained at the height of royal favour for the first two years of the reign of Charles I, until he was assassinated...

, and Mompesson's connection to George Villiers was the key to his later despotism. George Villiers became James I's favourite (and alleged lover), rising to the rank of Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham

The titles Marquess and Duke of Buckingham, referring to Buckingham, have been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been Earls of Buckingham.-1444 creation:...

by 1616, and Mompesson was quick to use his family connections. His infamous career was tied directly to that of George Villiers and James I.

In 1616, Mompesson used his influence to propose to Villiers that there be a commissioner of inns. Justices of the peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

were in charge of granting licences to taverns, but there was ambiguity about inns. While Fulke Greville

Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke

Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke, de jure 13th Baron Latimer and 5th Baron Willoughby de Broke , known before 1621 as Sir Fulke Greville, was an Elizabethan poet, dramatist, and statesman....

, the Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

, disapproved of the legal standing of Mompesson's plan, Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

, then the Attorney General

Attorney General for England and Wales

Her Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales, usually known simply as the Attorney General, is one of the Law Officers of the Crown. Along with the subordinate Solicitor General for England and Wales, the Attorney General serves as the chief legal adviser of the Crown and its government in...

, felt that it was legal, and Villiers urged the king to pressure the exchequer

Exchequer

The Exchequer is a government department of the United Kingdom responsible for the management and collection of taxation and other government revenues. The historical Exchequer developed judicial roles...

to approve the plan. Mompesson therefore became one of three commissioners of inns in 1617. The fines that he could levy against inns out of compliance was left to his discretion, and the fees that he could charge to license an inn were similarly up to his own judgment. His only constraint was that four-fifths of the money go to the Treasury. On November 18, 1616, James knight

Knight

A knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

ed Mompesson to give him more authority when dealing with innkeepers.

Mompesson's performance of his job was aggressive, unethical, and avaricious. He expanded his brief to licence taverns, which was clearly the historical realm of the Justices of the Peace, and he trespassed into the jurisdiction of the Justices in other ways as well. Justices of the Peace were responsible for keeping the domestic peace, and Mompesson would allow taverns closed for ill repute and bad behavior to reopen if they paid him a stiff bribe/fee.

In 1617, Mompesson proposed to Villiers and received a scheme to raise £10,000 in four years by selling decayed timber from royal lands. For performing this public service, he received £1,000 personally the first year, with another £1,000 due at the end of four years. Evidence would later show that he made over £10,000 profit beyond what he gave to the Treasury, as well as the £2,000. By the next year, his reputation was such that there was a backlash. Mompesson was given a second monopoly

Monopoly

A monopoly exists when a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular commodity...

, to investigate the production of gold

Cloth of gold

Cloth of gold is a fabric woven with a gold-wrapped or spun weft - referred to as "a spirally spun gold strip". In most cases, the core yarn is silk wrapped with a band or strip of high content gold filé...

and silver thread and to charge licensing fees to those who produced it. Furthermore, Mompesson was given the power to imprison those found guilty of producing gold and silver thread without a license. He immediately set about extorting money from goldsmith

Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Since ancient times the techniques of a goldsmith have evolved very little in order to produce items of jewelry of quality standards. In modern times actual goldsmiths are rare...

s in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. In 1619, Mompesson obtained a position as a surveyor of the profits of James I's New River Company

New River (England)

The New River is an artificial waterway in England, opened in 1613 to supply London with fresh drinking water taken from the River Lea and from Amwell Springs , and other springs and wells along its course....

, with a £200 annuity taken from the royal profits. In 1620, Mompesson was granted a licence to make charcoal from coal and, finally, a licence to find and recover "concealed" Crown lands (i.e., property over which the Crown

The Crown

The Crown is a corporation sole that in the Commonwealth realms and any provincial or state sub-divisions thereof represents the legal embodiment of governance, whether executive, legislative, or judicial...

's rights as landlord had fallen into abeyance

Abeyance

Abeyance is a state of expectancy in respect of property, titles or office, when the right to them is not vested in any one person, but awaits the appearance or determination of the true owner. In law, the term abeyance can only be applied to such future estates as have not yet vested or possibly...

or had not yet fully been realised). Any lands he discovered valued at less than £200 were his to keep, and those above were to be regulated, with fees, rents, and charges for ingress and egress. Naturally, Mompesson undervalued the lands he "found," consistently discovering them to be under the £200 threshold, and farmers were at high risk.

Backlash, trial, and banishment

The sentiment against Mompesson was very high in 1620, and Bacon warned Villiers to take away Mompesson's licensing of inns, in particular. Buckingham, however, continued to support him. Mompesson was returned to ParliamentParliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

in 1620, and investigations began immediately. In February 1621, the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

and House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

began investigating him on separate matters, with Commons investigating the inn licensures and Lords the gold thread. Among other damning evidence, there was one story of one of Mompesson's agents showing up at a tavern, claiming emergency, begging for a place to sleep, and then, the next morning, prosecuting the tavern keeper for running an unlicensed inn. Sir Edward Coke

Edward Coke

Sir Edward Coke SL PC was an English barrister, judge and politician considered to be the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. Born into a middle class family, Coke was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge before leaving to study at the Inner Temple, where he was called to the...

found that Mompesson had prosecuted over 3,320 inns and taverns on regulations dating back to Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

. Lords found that Mompesson had been guilty of extortion

Extortion

Extortion is a criminal offence which occurs when a person unlawfully obtains either money, property or services from a person, entity, or institution, through coercion. Refraining from doing harm is sometimes euphemistically called protection. Extortion is commonly practiced by organized crime...

.

Mompesson's response was to admit his guilt and plead for mercy

Mercy

Mercy is broad term that refers to benevolence, forgiveness and kindness in a variety of ethical, religious, social and legal contexts.The concept of a "Merciful God" appears in various religions from Christianity to...

. He then attempted to blame Bacon for finding the inn scheme legal in the first place. Commons preferred charges to Lords, waiting sentencing, and Mompesson was ordered to attend every day and to be guarded by the Sergeant-at-Arms. On March 3, 1621, Mompesson fled to France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. The next week, the sentence came down. Mompesson was ordered to pay a £10,000 fine, lose his knighthood, and ride down the Strand

Strand, London

Strand is a street in the City of Westminster, London, England. The street is just over three-quarters of a mile long. It currently starts at Trafalgar Square and runs east to join Fleet Street at Temple Bar, which marks the boundary of the City of London at this point, though its historical length...

facing backwards from his horse, and then be imprisoned for life. A few days later, they added banishment for life to the penalty. Further, he was decried as an eternally notorious criminal.

His wife, Katherine, stayed in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. She petitioned Charles I for relief, asking that her husband be allowed to return to dispense with his estate, since it was entangled. Commons ordered that all of Mompesson's gains be forfeit, except for the New River annuity, which would go to Katherine. The fine devolved to John St. John. In 1623, Charles gave Mompesson three months to be in England, a period which was later extended. The House of Commons ordered him out of the country on February 8, 1624, but he was back in the country soon after. He lived in Wiltshire in retirement for the rest of his life. During his later years, his name was not forgotten by Parliamentarian

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

forces. He was a Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

during the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

and visited the king, though he did not take part. His own will was tested in court and proved on August 3, 1663, so he died some (probably short) time before that date.