Elgiva

Encyclopedia

Ælfgifu was the consort of King Eadwig of England

(r. 955–59) for a brief period of time until 957 or 958. What little is known of her comes primarily by way of Anglo-Saxon charters

, possibly including a will

, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

and hostile anecdotes in works of hagiography. Her union with the king, annulled within a few years of Eadwig's reign, seems to have been a target for factional rivalries which surrounded the throne in the late 950s. By c. 1000, when the careers of the Benedictine reformers Dunstan

and Oswald

became the subject of hagiography, its memory had suffered heavy degradation. In the mid-960s, however, she appears to have become a well-to-do landowner on good terms with King Edgar and through her will, a generous benefactress of ecclesiastical houses associated with the royal family, notably the Old Minster

and New Minster

at Winchester

.

Two facts about Ælfgifu's family background are unambiguously stated by the sources. First, her mother bore the name of Æthelgifu, a woman of very high birth (natione præcelsa). Second, she was related to her husband Eadwig, since in 958 their marriage was dissolved by Archbishop Oda on grounds that they were too closely related by blood, that is, within the forbidden degrees of consanguinity. Ælfgifu has been also identified with the namesake who left a will sometime between 966 and 975, which might shed further light on her origins.

Two facts about Ælfgifu's family background are unambiguously stated by the sources. First, her mother bore the name of Æthelgifu, a woman of very high birth (natione præcelsa). Second, she was related to her husband Eadwig, since in 958 their marriage was dissolved by Archbishop Oda on grounds that they were too closely related by blood, that is, within the forbidden degrees of consanguinity. Ælfgifu has been also identified with the namesake who left a will sometime between 966 and 975, which might shed further light on her origins.

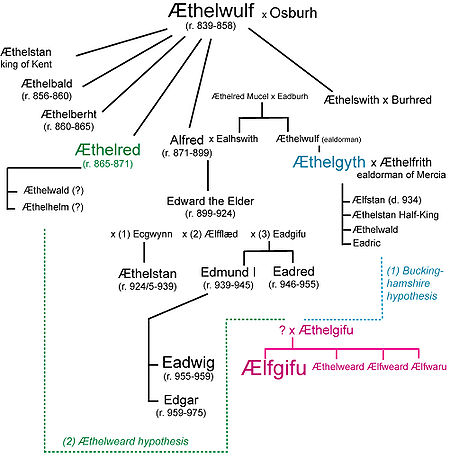

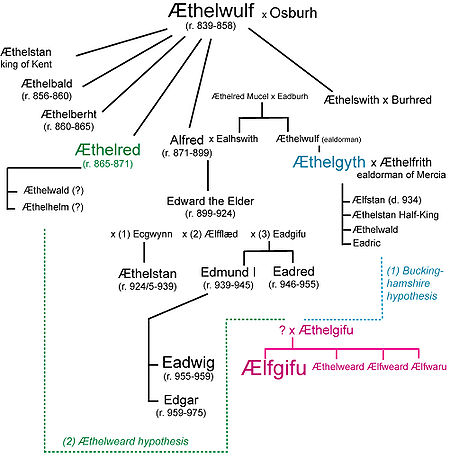

These dangling clues, unsatisfying as they are in themselves, have been used to construct two possible—-and possibly compatible—-genealogies for Ælfgifu, both of which ascribe to her a degree of royal rank. One theory espoused by Cyril Hart and considered by Pauline Stafford

makes her a noblewoman of Mercian stock, who descended from Ealdorman Æthelfrith of Mercia and his wife Æthelgyth, who may have been a daughter of ealdorman Æthelwulf and a niece of King Alfred's Mercian consort Ealhswith

. This reconstruction is based on the probability that Risborough (Buckinghamshire), one of Ælfgifu’s holdings mentioned in the will, was previously held by Æthelgyth. The possible implication is that Ælfgifu inherited the estate and many others in Buckinghamshire. Given that she asked Bishop Æthelwold, one of her beneficiaries, to intercede for her "mother's soul", she may have done so through the maternal line. If the suggestion is correct, she would have been closely related to the politically prominent family of ealdorman Æthelstan Half-King

and his offspring.

Her supposed will also provides the starting point for another, more widely regarded hypothesis. In this document, she makes bequests to Ælfweard and Æthelweard, seemingly her brothers (one of whom was married to Æthelflæd), and to her sister Ælfwaru. Æthelweard and Ælfweard re-appear as brothers and thegns (ministri) in the witness list of a spurious royal charter dated 974 This appears to be the same Æthelweard who regularly attests royal charters between 958 and 977 as the king's thegn and may have moved on to become the illustrious ealdorman of the Western Provinces and author of a Latin chronicle, in which he claimed descent from King Æthelred of Wessex (d. 871), fourth son of King Æthelwulf. The conclusion which can be derived from these prosopographical byways is that if the ealdorman and chronicler Æthelweard was her brother, she must have shared with him a common ancestor in King Æthelred. In this light, Ælfgifu would have been Eadwig’s third cousin once removed.

The two genealogies are not mutually exclusive. Andrew Wareham

suggests that these two different branches of the royal family may have come together in the marriage which produced Ælfgifu. In view of the will´s special mention of Ælfgifu´s "mother's soul", this could mean that Æthelgifu was a descendant of Æthelgyth, while the anonymous father traced his descent to Æthelred.

Neither hypothesis is conclusive. A weakness shared by these suggestions is that they hinge on the assumption that the testatrix Ælfgifu is the same as the erstwhile royal consort. However, for reasons explored below, the identification is favoured by most historians, though usually with reservations.

At an unknown date around the time of his accession, the young King Eadwig married Ælfgifu. The union was or was to become one of the most controversial royal marriages in 10th-century England. Eadwig's brother Edgar was the heir presumptive

At an unknown date around the time of his accession, the young King Eadwig married Ælfgifu. The union was or was to become one of the most controversial royal marriages in 10th-century England. Eadwig's brother Edgar was the heir presumptive

, but a legitimate son born out of this marriage would have seriously diminished Edgar’s chances of succeeding to the kingship, especially if both parents were of royal rank. Fostered by Ælfwynn wife of Æthelstan Half-King

together with her son Æthelwine

, Edgar enjoyed the support of Æthelstan Half-King

(d. after 957) and his sons, whose power base was concentrated in Mercia and East Anglia and who would not have liked to lose power and influence to Ælfgifu's kinsmen and associates. If Hart's suggestion that Ælfgifu was of royal Mercian descent and related to the latter family is correct, it might have been hoped that the marriage would give Eadwig some political advantage in exercising West-Saxon control over Mercia.

Ælfgifu's mother, Æthelgifu, seems to have played a decisive role in her rise to prominence by the king's side, as indicated by their joint appearances in the sources. Together they witness a charter which records an exchange of land between Bishop Brihthelm and Æthelwold, then abbot of Abingdon. and both their names occur among “illustrious” benefactors on a leaf of the early 11th-century Liber Vitae of the New Minster, Winchester. In her presumed will (see above), Ælfgifu asks Bishop Æthelwold, one of her beneficiaries, to intercede for her and her mother.

It is probable that they are the two women who are portrayed as Eadwig's sexual partners in the Life of St Dunstan by author 'B' and that of St. Oswald by Byrhtferth of Ramsey, both dating from around 1000. Dunstan's Life alleges that on the banquet following the solemnity of his coronation at Kingston (Surrey)

, Eadwig left the table and retreated to his chamber to debauch himself with two women, an indecent noblewoman (quaedam, licet natione præcelsa, inepta tamen mulier), later identified as Æthelgifu, and her daughter of ripe age (adulta filia). They are said to have attached themselves to him "obviously in order to join and ally herself or else her daughter to him in lawful marriage.". Shocked by Eadwig's unseemly withdrawal, the nobles sent Dunstan and Bishop Cynesige, who forcefully dragged the king back to the feast. For this act, Dunstan had incurred the enmity of the king, who sent him into exile at Æthelgifu’s instigation. Called a modern Jezebel

, she would have exploited Eadwig’s anger by ordering Dunstan's persecution and the spoliation of his property. That the memory of Eadwig’s sexual affairs had become tainted and confused around the turn of the century is suggested by Byrhferth’s Life of St. Oswald, which has a more fantastic tale to tell about Eadwig’s two women. It recounts that the king was married, but ran off with a lady who was below his wife’s rank. Archbishop Oda personally seized the king’s new mistress at her home, forced her out of the country and managed to correct the king’s behaviour.

These stories, written down some 40-odd years later, seem to be rooted in later smear campaigns which were meant to bring disrepute on Eadwig and his marital relations. Although both Lives focus on the personal dimension of the affairs from the perspective of their protagonists, the effects of factional rivalries loom in the background. It is known that in 958 Archbishop Oda of Canterbury

, a supporter of Dunstan, annulled the marriage of Eadwig and Ælfgifu on the basis of their consanguinity. The underlying motif for this otherwise surprisingly belated decision may well have been political rather than religious or legal. It bolstered Edgar's status as heir to the throne. There is a good possibility that Oda’s act had been spurred on by Edgar’s sympathisers, the sons of Æthelstan Half-King

, and in particular by their ally Dunstan

, whose monastic reform they generously supported.

The event needs to be placed in the broader context of Eadwig's struggle to retain political control and of the factions which supported Edgar as the heir presumptive. In the summer of 957, Edgar was elected king of Mercia. Author 'B' presents this as the outcome of a northern revolt against Eadwig, whereby he lost control north of the Thames (Mercia and Northumbria) and Edgar was set up as king over that part of England. This is a gross exaggeration, since Eadwig retained the title "king of the English" in his charters and Æthelweard envisaged a "continuous" reign. Edgar's description as regulus in an alliterative charter of 956 may even signify that there was a prior agreement that Edgar would become his brother's subking in Mercia as soon as he reached majority. The weakness of Eadwig's political position is nevertheless confirmed by Bishop Æthelwold's retrospective note of complaint that Eadwig "had through the ignorance of childhood dispersed his kingdom and divided its unity".

While it appears then that Dunstan and Archbishop Oda opposed the marriage, it was not all hostility that Ælfgifu had to endure from ecclesiastical magnates. Another Benedictine reformer, Æthelwold

, abbot of Abingdon and later bishop of Winchester, seems to have preferred to support her, even if he was not uncritical of her husband's reign. One of the few charters to have been witnessed by Ælfgifu is the aforementioned memorandum from Abingdon, which confirms an exchange of land between Æthelwold and Brihthelm. In the subscription, she is recognised as the king’s wife (þæs cininges wif). Ælfgifu’s will, if it can be ascribed to her, provides even clearer evidence for her close association with Æthelwold.

No less important than the circumstances of her married life is the way Ælfgifu may have pushed on since the break-up of her marriage and more especially since the autumn of 959, when Eadwig died (1 October 959) and was succeeded by his brother Edgar

No less important than the circumstances of her married life is the way Ælfgifu may have pushed on since the break-up of her marriage and more especially since the autumn of 959, when Eadwig died (1 October 959) and was succeeded by his brother Edgar

as king of all England. The vitae are unhelpful at this point. Byrhtferth writes that Eadwig's mistress was exiled by Oda (d. 958), but his account of the archbishop's intervention is dubious and only faintly echoes the historical information of the Chronicle. Less credible still is the tale recorded by Osbern in the late 11th century. Adopting B's depiction of Edgar's Mercian reign as the outcome of a very coup against Eadwig, he amplifies the story by suggesting that Eadwig's mistress (adultera) was hamstrung

in an ambush by Mercian resurgents and died not long thereafter.

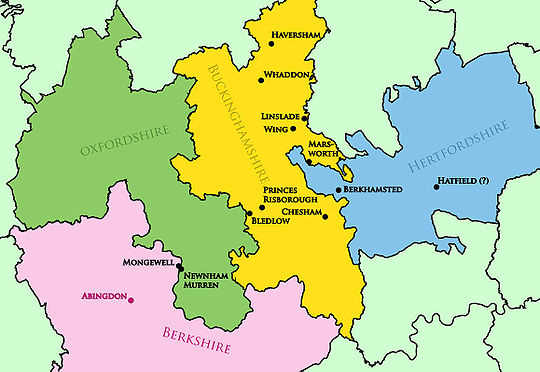

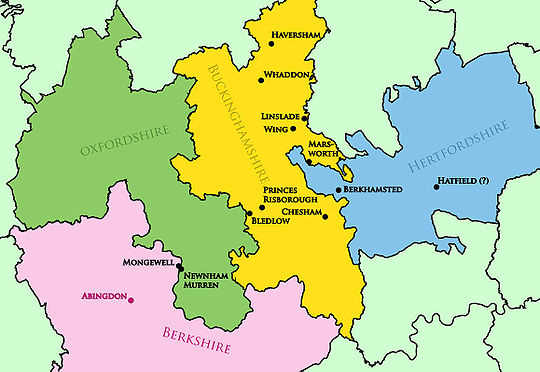

Whether Ælfgifu kept a low profile or truly lived in exile, as Byrhtferth appears to claim, there is evidence to suggest that by the mid-960s, she had come to enjoy some peace, prosperity and a good understanding with King Edgar and the royal house. This picture is based on her identification with the Ælfgifu who was a wealthy landowner in Southeast England and a relative of King Edgar. She appears under Edgar’s patronage in two royal charters of AD 966, in which he calls her "a certain noble matron (matrona) who is connected to me by the relationship of worldly blood". Sometime before Edgar's death (975), she left a will in which she bequeathed extensive estates in Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Hertfordshire, considerable sums of money and various objects of value to (1) ecclesiastical houses (Old and New Minster, Abingdon Abbey

, Romsey Abbey

and Bath Abbey

), (2) Bishop Æthelwold (in person), (3) members of the royal family (Edgar, Queen Ælfthryth and Edward the Martyr

), and (4) her closest relatives (her two brothers, her sister and her brother's wife). The most substantial bequests are those to King Edgar and the Old Minster, which received the vast estate at Princes Risborough amounting to 30 hide

s. No children are mentioned. Exceptionally high status is suggested by a gift or payment to Edgar which has been interpreted as her heriot

, consisting of two armlets of 120 mancuses each, a drinking-cup, 6 horses, 6 shields and 6 spears. There is no conclusive proof, but that the two Ælfgifus are identical is strongly suggested by their intimate association with the royal family, Bishop Æthelwold, the New Minster at Winchester and with their own mother.

Sadly, the conditions of Ælfgifu's return to fortune remain unclear. It would have been important to know, for instance, how and what on terms she came to hold the estates mentioned in her will. Those at Newnham Murren

and Linslade

were previously granted to her by King Edgar and now returned to the royal family, but it is impossible to determine which of the other estates were part of her dower

property and which were inherited or acquired otherwise. As noted earlier, a case has been made for Princes Risborough

as having been passed on through the maternal line. If the other holdings were likewise her own, the rehabilitation of her position may have come at a great price, one which considerably enriched the royal family with land north of the Thames.

Although in the two charters of 966, Edgar showed generosity and recognised the bonds of kinship, it has been asked how much of it was driven by pressure rather than good will. In favour of the former, Andrew Wareham has suggested that in naming his third and most 'throneworthy' son (b. after c. 964) Æthelred, after his great-great-uncle and thus after Ælfgifu's and Æthelweard's ancestor (see genealogy ↑), Edgar may have intended to make a sympathetic gesture by which he stressed their kinship.

In her will, Ælfgifu associates her endowments of "God's church" with the salvation of both her and Edgar's soul, which suggests that she expressed a shared interest in the Benedictine reform, of which Edgar was a generous sponsor and Bishop Æthelwold a prominent conductor. In turn, she may have hoped that he would put her grants to good and pious use. According to the Libellus Æthelwoldi, such seems to have come true in the case of Marsworth

, which he donated to Ely Abbey, refounded by Bishop Æthelwold in 970.

An intriguing aspect of Ælfgifu's will is the way in which it may have been used to tie her kin-group and associates more closely in a beneficial relationship with the royal family and the leading ecclesiastical establishments, or else to reaffirm the association. This is seen at its most straightforward when she addresses Edgar with a special request: "I beseech my royal lord for the love of God, that he will not desert my men who seek his protection and are worthy of him." She also made sure that Mongewell, near Edward's new estate at Newnham Murren, and Berkhampstead did not pass directly to the community of the Old Minster, but was first leased by her siblings on the condition that they rendered a food-rent (feorm) to the two minsters every year.

While Eadwig, like Alfred and Edward, was buried in the New Minster, Ælfgifu intended her body to be buried in the nearby Old Minster. At Winchester, Ælfgifu was dearly remembered for her generosity and conceivably so was her mother: Ælfgyfu coniunx Eadwigi regis and Æþelgyfu, who may be her mother, appear on a page of the New Minster Liber Vitae of 1031 among the illustrious benefactresses of the community.

----

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

(r. 955–59) for a brief period of time until 957 or 958. What little is known of her comes primarily by way of Anglo-Saxon charters

Anglo-Saxon Charters

Anglo-Saxon charters are documents from the early medieval period in Britain which typically make a grant of land or record a privilege. The earliest surviving charters were drawn up in the 670s; the oldest surviving charters granted land to the Church, but from the eighth century surviving...

, possibly including a will

Will (law)

A will or testament is a legal declaration by which a person, the testator, names one or more persons to manage his/her estate and provides for the transfer of his/her property at death...

, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

and hostile anecdotes in works of hagiography. Her union with the king, annulled within a few years of Eadwig's reign, seems to have been a target for factional rivalries which surrounded the throne in the late 950s. By c. 1000, when the careers of the Benedictine reformers Dunstan

Dunstan

Dunstan was an Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, a Bishop of Worcester, a Bishop of London, and an Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in England and reformed the English Church...

and Oswald

Oswald of Worcester

Oswald of Worcester was Archbishop of York from 972 to his death in 992. He was of Danish ancestry, but brought up by his uncle, Oda, who sent him to France to the abbey of Fleury to become a monk. After a number of years at Fleury, Oswald returned to England at the request of his uncle, who died...

became the subject of hagiography, its memory had suffered heavy degradation. In the mid-960s, however, she appears to have become a well-to-do landowner on good terms with King Edgar and through her will, a generous benefactress of ecclesiastical houses associated with the royal family, notably the Old Minster

Old Minster, Winchester

The Old Minster was the Anglo-Saxon cathedral for the diocese of Wessex and then Winchester from 660 to 1093. It stood on a site immediately north of and partially beneath its successor, Winchester Cathedral....

and New Minster

New Minster, Winchester

The New Minster, Winchester was a royal Benedictine abbey founded in 901 in Winchester in the English county of Hampshire.Alfred the Great had intended to build the monastery, but only got around to buying the land. His son, Edward the Elder, finished the project according to Alfred's wishes, with...

at Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

.

Family background

These dangling clues, unsatisfying as they are in themselves, have been used to construct two possible—-and possibly compatible—-genealogies for Ælfgifu, both of which ascribe to her a degree of royal rank. One theory espoused by Cyril Hart and considered by Pauline Stafford

Pauline Stafford

Pauline Stafford is Professor Emerita of Early Medieval History at Liverpool University in England. Her work focuses on the history of women and gender in England from the eighth to the early twelfth centuries, and on the same topics in Frankish history during the eighth and ninth centuries...

makes her a noblewoman of Mercian stock, who descended from Ealdorman Æthelfrith of Mercia and his wife Æthelgyth, who may have been a daughter of ealdorman Æthelwulf and a niece of King Alfred's Mercian consort Ealhswith

Ealhswith

Ealhswith or Ealswitha was the daughter of a Mercian nobleman, Æthelred Mucil, Ealdorman of the Gaini. She was married in 868 to Alfred the Great, before he became king of Wessex. In accordance with ninth century West Saxon custom, she was not given the title of queen. -Life:Ealswith was the...

. This reconstruction is based on the probability that Risborough (Buckinghamshire), one of Ælfgifu’s holdings mentioned in the will, was previously held by Æthelgyth. The possible implication is that Ælfgifu inherited the estate and many others in Buckinghamshire. Given that she asked Bishop Æthelwold, one of her beneficiaries, to intercede for her "mother's soul", she may have done so through the maternal line. If the suggestion is correct, she would have been closely related to the politically prominent family of ealdorman Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan , commonly called Æthelstan Half-King, was Ealdorman of East Anglia and the leading member of a very prominent Anglo-Saxon family. Æthelstan became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey in 957.-Origins and career:...

and his offspring.

Her supposed will also provides the starting point for another, more widely regarded hypothesis. In this document, she makes bequests to Ælfweard and Æthelweard, seemingly her brothers (one of whom was married to Æthelflæd), and to her sister Ælfwaru. Æthelweard and Ælfweard re-appear as brothers and thegns (ministri) in the witness list of a spurious royal charter dated 974 This appears to be the same Æthelweard who regularly attests royal charters between 958 and 977 as the king's thegn and may have moved on to become the illustrious ealdorman of the Western Provinces and author of a Latin chronicle, in which he claimed descent from King Æthelred of Wessex (d. 871), fourth son of King Æthelwulf. The conclusion which can be derived from these prosopographical byways is that if the ealdorman and chronicler Æthelweard was her brother, she must have shared with him a common ancestor in King Æthelred. In this light, Ælfgifu would have been Eadwig’s third cousin once removed.

The two genealogies are not mutually exclusive. Andrew Wareham

Andrew Wareham

Andrew Wareham is a British historian who has written several books on the Economy of England in the Middle Ages with a special interest in the Hearth Tax. He is currently employed as a reader in the department of humanities at Roehampton University, London....

suggests that these two different branches of the royal family may have come together in the marriage which produced Ælfgifu. In view of the will´s special mention of Ælfgifu´s "mother's soul", this could mean that Æthelgifu was a descendant of Æthelgyth, while the anonymous father traced his descent to Æthelred.

Neither hypothesis is conclusive. A weakness shared by these suggestions is that they hinge on the assumption that the testatrix Ælfgifu is the same as the erstwhile royal consort. However, for reasons explored below, the identification is favoured by most historians, though usually with reservations.

Marriage

Heir Presumptive

An heir presumptive or heiress presumptive is the person provisionally scheduled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir or heiress apparent or of a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question...

, but a legitimate son born out of this marriage would have seriously diminished Edgar’s chances of succeeding to the kingship, especially if both parents were of royal rank. Fostered by Ælfwynn wife of Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan , commonly called Æthelstan Half-King, was Ealdorman of East Anglia and the leading member of a very prominent Anglo-Saxon family. Æthelstan became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey in 957.-Origins and career:...

together with her son Æthelwine

Æthelwine, Ealdorman of East Anglia

Æthelwine was ealdorman of East Anglia and one of the leading noblemen in the kingdom of England in the later 10th century. As with his kinsmen, the principal source for his life is Byrhtferth's life of Oswald of Worcester...

, Edgar enjoyed the support of Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan , commonly called Æthelstan Half-King, was Ealdorman of East Anglia and the leading member of a very prominent Anglo-Saxon family. Æthelstan became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey in 957.-Origins and career:...

(d. after 957) and his sons, whose power base was concentrated in Mercia and East Anglia and who would not have liked to lose power and influence to Ælfgifu's kinsmen and associates. If Hart's suggestion that Ælfgifu was of royal Mercian descent and related to the latter family is correct, it might have been hoped that the marriage would give Eadwig some political advantage in exercising West-Saxon control over Mercia.

Ælfgifu's mother, Æthelgifu, seems to have played a decisive role in her rise to prominence by the king's side, as indicated by their joint appearances in the sources. Together they witness a charter which records an exchange of land between Bishop Brihthelm and Æthelwold, then abbot of Abingdon. and both their names occur among “illustrious” benefactors on a leaf of the early 11th-century Liber Vitae of the New Minster, Winchester. In her presumed will (see above), Ælfgifu asks Bishop Æthelwold, one of her beneficiaries, to intercede for her and her mother.

It is probable that they are the two women who are portrayed as Eadwig's sexual partners in the Life of St Dunstan by author 'B' and that of St. Oswald by Byrhtferth of Ramsey, both dating from around 1000. Dunstan's Life alleges that on the banquet following the solemnity of his coronation at Kingston (Surrey)

Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames is the principal settlement of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames in southwest London. It was the ancient market town where Saxon kings were crowned and is now a suburb situated south west of Charing Cross. It is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the...

, Eadwig left the table and retreated to his chamber to debauch himself with two women, an indecent noblewoman (quaedam, licet natione præcelsa, inepta tamen mulier), later identified as Æthelgifu, and her daughter of ripe age (adulta filia). They are said to have attached themselves to him "obviously in order to join and ally herself or else her daughter to him in lawful marriage.". Shocked by Eadwig's unseemly withdrawal, the nobles sent Dunstan and Bishop Cynesige, who forcefully dragged the king back to the feast. For this act, Dunstan had incurred the enmity of the king, who sent him into exile at Æthelgifu’s instigation. Called a modern Jezebel

Jezebel (Bible)

Jezebel was a princess, identified in the Hebrew Book of Kings as the daughter of Ethbaal, King of Tyre and the wife of Ahab, king of north Israel. According to genealogies given in Josephus and other classical sources, she was the great-aunt of Dido, Queen of Carthage.The Hebrew text portrays...

, she would have exploited Eadwig’s anger by ordering Dunstan's persecution and the spoliation of his property. That the memory of Eadwig’s sexual affairs had become tainted and confused around the turn of the century is suggested by Byrhferth’s Life of St. Oswald, which has a more fantastic tale to tell about Eadwig’s two women. It recounts that the king was married, but ran off with a lady who was below his wife’s rank. Archbishop Oda personally seized the king’s new mistress at her home, forced her out of the country and managed to correct the king’s behaviour.

These stories, written down some 40-odd years later, seem to be rooted in later smear campaigns which were meant to bring disrepute on Eadwig and his marital relations. Although both Lives focus on the personal dimension of the affairs from the perspective of their protagonists, the effects of factional rivalries loom in the background. It is known that in 958 Archbishop Oda of Canterbury

Oda the Severe

Oda , called the Good or the Severe, was a 10th-century Archbishop of Canterbury in England.-Early career:...

, a supporter of Dunstan, annulled the marriage of Eadwig and Ælfgifu on the basis of their consanguinity. The underlying motif for this otherwise surprisingly belated decision may well have been political rather than religious or legal. It bolstered Edgar's status as heir to the throne. There is a good possibility that Oda’s act had been spurred on by Edgar’s sympathisers, the sons of Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan Half-King

Æthelstan , commonly called Æthelstan Half-King, was Ealdorman of East Anglia and the leading member of a very prominent Anglo-Saxon family. Æthelstan became a monk at Glastonbury Abbey in 957.-Origins and career:...

, and in particular by their ally Dunstan

Dunstan

Dunstan was an Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey, a Bishop of Worcester, a Bishop of London, and an Archbishop of Canterbury, later canonised as a saint. His work restored monastic life in England and reformed the English Church...

, whose monastic reform they generously supported.

The event needs to be placed in the broader context of Eadwig's struggle to retain political control and of the factions which supported Edgar as the heir presumptive. In the summer of 957, Edgar was elected king of Mercia. Author 'B' presents this as the outcome of a northern revolt against Eadwig, whereby he lost control north of the Thames (Mercia and Northumbria) and Edgar was set up as king over that part of England. This is a gross exaggeration, since Eadwig retained the title "king of the English" in his charters and Æthelweard envisaged a "continuous" reign. Edgar's description as regulus in an alliterative charter of 956 may even signify that there was a prior agreement that Edgar would become his brother's subking in Mercia as soon as he reached majority. The weakness of Eadwig's political position is nevertheless confirmed by Bishop Æthelwold's retrospective note of complaint that Eadwig "had through the ignorance of childhood dispersed his kingdom and divided its unity".

While it appears then that Dunstan and Archbishop Oda opposed the marriage, it was not all hostility that Ælfgifu had to endure from ecclesiastical magnates. Another Benedictine reformer, Æthelwold

Æthelwold

-Royalty and nobility:*King Æthelwold of Deira, King of Deira, d. 655*King Æthelwold of East Anglia, King of East Anglia, d. 664*King Æthelwold Moll of Northumbria, King of Northumbria, d. post-765*Æthelwold of Wessex, son of King Æthelred of Wessex, d. 902...

, abbot of Abingdon and later bishop of Winchester, seems to have preferred to support her, even if he was not uncritical of her husband's reign. One of the few charters to have been witnessed by Ælfgifu is the aforementioned memorandum from Abingdon, which confirms an exchange of land between Æthelwold and Brihthelm. In the subscription, she is recognised as the king’s wife (þæs cininges wif). Ælfgifu’s will, if it can be ascribed to her, provides even clearer evidence for her close association with Æthelwold.

Dowagerhood

Edgar of England

Edgar the Peaceful, or Edgar I , also called the Peaceable, was a king of England . Edgar was the younger son of Edmund I of England.-Accession:...

as king of all England. The vitae are unhelpful at this point. Byrhtferth writes that Eadwig's mistress was exiled by Oda (d. 958), but his account of the archbishop's intervention is dubious and only faintly echoes the historical information of the Chronicle. Less credible still is the tale recorded by Osbern in the late 11th century. Adopting B's depiction of Edgar's Mercian reign as the outcome of a very coup against Eadwig, he amplifies the story by suggesting that Eadwig's mistress (adultera) was hamstrung

Hamstringing

Hamstringing is a method of crippling a person or animal so that they cannot walk properly, by cutting the two large tendons at the back of the knees.- Method :...

in an ambush by Mercian resurgents and died not long thereafter.

Whether Ælfgifu kept a low profile or truly lived in exile, as Byrhtferth appears to claim, there is evidence to suggest that by the mid-960s, she had come to enjoy some peace, prosperity and a good understanding with King Edgar and the royal house. This picture is based on her identification with the Ælfgifu who was a wealthy landowner in Southeast England and a relative of King Edgar. She appears under Edgar’s patronage in two royal charters of AD 966, in which he calls her "a certain noble matron (matrona) who is connected to me by the relationship of worldly blood". Sometime before Edgar's death (975), she left a will in which she bequeathed extensive estates in Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Hertfordshire, considerable sums of money and various objects of value to (1) ecclesiastical houses (Old and New Minster, Abingdon Abbey

Abingdon Abbey

Abingdon Abbey was a Benedictine monastery also known as St Mary's Abbey located in Abingdon, historically in the county of Berkshire but now in Oxfordshire, England.-History:...

, Romsey Abbey

Romsey Abbey

Romsey Abbey is a parish church of the Church of England in Romsey, a market town in Hampshire, England. Until the dissolution it was the church of a Benedictine nunnery.-Background:...

and Bath Abbey

Bath Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Bath, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is an Anglican parish church and a former Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, England...

), (2) Bishop Æthelwold (in person), (3) members of the royal family (Edgar, Queen Ælfthryth and Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr was king of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar, but not his father's acknowledged heir...

), and (4) her closest relatives (her two brothers, her sister and her brother's wife). The most substantial bequests are those to King Edgar and the Old Minster, which received the vast estate at Princes Risborough amounting to 30 hide

Hide (unit)

The hide was originally an amount of land sufficient to support a household, but later in Anglo-Saxon England became a unit used in assessing land for liability to "geld", or land tax. The geld would be collected at a stated rate per hide...

s. No children are mentioned. Exceptionally high status is suggested by a gift or payment to Edgar which has been interpreted as her heriot

Heriot

Heriot, from Old English heregeat , was originally a death-duty in late Anglo-Saxon England, which required that at death, a nobleman provided to his king a given set of military equipment, often including horses, swords, shields, spears and helmets...

, consisting of two armlets of 120 mancuses each, a drinking-cup, 6 horses, 6 shields and 6 spears. There is no conclusive proof, but that the two Ælfgifus are identical is strongly suggested by their intimate association with the royal family, Bishop Æthelwold, the New Minster at Winchester and with their own mother.

Sadly, the conditions of Ælfgifu's return to fortune remain unclear. It would have been important to know, for instance, how and what on terms she came to hold the estates mentioned in her will. Those at Newnham Murren

Newnham Murren

Newnham Murren is a village in the Thames Valley in South Oxfordshire, about east of the market town of Wallingford. Newnham Murren is in the civil parish of Crowmarsh and is now contiguous with the village of Crowmarsh Gifford.-History:...

and Linslade

Linslade

Linslade is an English town, located on the Bedfordshire side of the Bedfordshire-Buckinghamshire border . It abuts onto the town of Leighton Buzzard with which it forms the civil parish of Leighton-Linslade. Linslade was transferred from Buckinghamshire in 1965, and was previously a separate...

were previously granted to her by King Edgar and now returned to the royal family, but it is impossible to determine which of the other estates were part of her dower

Dower

Dower or morning gift was a provision accorded by law to a wife for her support in the event that she should survive her husband...

property and which were inherited or acquired otherwise. As noted earlier, a case has been made for Princes Risborough

Princes Risborough

Princes Risborough is a small town in Buckinghamshire, England, about 9 miles south of Aylesbury and 8 miles north west of High Wycombe. Bledlow lies to the west and Monks Risborough to the east. It lies at the foot of the Chiltern Hills, at the north end of a gap or pass through the Chilterns,...

as having been passed on through the maternal line. If the other holdings were likewise her own, the rehabilitation of her position may have come at a great price, one which considerably enriched the royal family with land north of the Thames.

Although in the two charters of 966, Edgar showed generosity and recognised the bonds of kinship, it has been asked how much of it was driven by pressure rather than good will. In favour of the former, Andrew Wareham has suggested that in naming his third and most 'throneworthy' son (b. after c. 964) Æthelred, after his great-great-uncle and thus after Ælfgifu's and Æthelweard's ancestor (see genealogy ↑), Edgar may have intended to make a sympathetic gesture by which he stressed their kinship.

In her will, Ælfgifu associates her endowments of "God's church" with the salvation of both her and Edgar's soul, which suggests that she expressed a shared interest in the Benedictine reform, of which Edgar was a generous sponsor and Bishop Æthelwold a prominent conductor. In turn, she may have hoped that he would put her grants to good and pious use. According to the Libellus Æthelwoldi, such seems to have come true in the case of Marsworth

Marsworth

Marsworth is a village and also a civil parish within Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. It is about two miles north of Tring, in Hertfordshire and six miles east of Aylesbury.-Early history:...

, which he donated to Ely Abbey, refounded by Bishop Æthelwold in 970.

An intriguing aspect of Ælfgifu's will is the way in which it may have been used to tie her kin-group and associates more closely in a beneficial relationship with the royal family and the leading ecclesiastical establishments, or else to reaffirm the association. This is seen at its most straightforward when she addresses Edgar with a special request: "I beseech my royal lord for the love of God, that he will not desert my men who seek his protection and are worthy of him." She also made sure that Mongewell, near Edward's new estate at Newnham Murren, and Berkhampstead did not pass directly to the community of the Old Minster, but was first leased by her siblings on the condition that they rendered a food-rent (feorm) to the two minsters every year.

While Eadwig, like Alfred and Edward, was buried in the New Minster, Ælfgifu intended her body to be buried in the nearby Old Minster. At Winchester, Ælfgifu was dearly remembered for her generosity and conceivably so was her mother: Ælfgyfu coniunx Eadwigi regis and Æþelgyfu, who may be her mother, appear on a page of the New Minster Liber Vitae of 1031 among the illustrious benefactresses of the community.

BENEFICIARY BEQUEST Ecclesiastical houses: Old Minster, Winchester estate at Princes Risborough Princes RisboroughPrinces Risborough is a small town in Buckinghamshire, England, about 9 miles south of Aylesbury and 8 miles north west of High Wycombe. Bledlow lies to the west and Monks Risborough to the east. It lies at the foot of the Chiltern Hills, at the north end of a gap or pass through the Chilterns,...

(Bucks.), except manumitted slaves+ 200 mancuses of gold, her shrine with relics + Estates at Mongewell MongewellMongewell is a village in the civil parish of Crowmarsh, about south of Wallingford in Oxfordshire. Mongewell is on the east bank of the Thames, linked with the west bank at Winterbrook by the nearby Winterbrook Bridge...

(Oxon.) and Berkhampstead (Herts.), see below.New Minster, Winchester estate at Bledlow BledlowBledlow is a village in the civil parish of Bledlow-cum-Saunderton in Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated about a mile and a half WSW of Princes Risborough, and on the border with Oxfordshire....

(Bucks.)+ 100 mancuses of gold Nunnaminster (St Mary's Abbey), Winchester a paten PatenA paten, or diskos, is a small plate, usually made of silver or gold, used to hold Eucharistic bread which is to be consecrated. It is generally used during the service itself, while the reserved hosts are stored in the Tabernacle in a ciborium....

(offring-disc)Nunnery of Christ and St Mary at Romsey Romsey AbbeyRomsey Abbey is a parish church of the Church of England in Romsey, a market town in Hampshire, England. Until the dissolution it was the church of a Benedictine nunnery.-Background:...

(Hants.), refounded by Edgar in 967.estate at Whaddon Whaddon, BuckinghamshireFor other villages with the same name, see Whaddon.Whaddon is a village and also a civil parish within Aylesbury Vale district, in Buckinghamshire.The village name is Anglo Saxon in origin, and means 'hill where wheat is grown'...

(Bucks.)Abingdon Abbey Chesham CheshamChesham is a market town in the Chiltern Hills, Buckinghamshire, England. It is located 11 miles south-east of the county town of Aylesbury. Chesham is also a civil parish designated a town council within Chiltern district. It is situated in the Chess Valley and surrounded by farmland, as well as...

(Bucks.)Bath Abbey Wickham (Wicham), possibly in Berkshire Wickham, BerkshireWickham is a village in Welford civil parish about north-west of Newbury, Berkshire. The M4 motorway passes just north of the village.-Archaeology:...

or further south, HampshireWickhamWickham, formerly spelled Wykeham, is a small historic village and civil parish in Hampshire, southern England, located about three miles north of Fareham. It is within the City of Winchester local government district, although it is considerably closer to Fareham than to Winchester...

, but the place-name is too common for identification.Royal family King Edgar estates at Wing Wing, BuckinghamshireWing is a village and civil parish in Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. The village is on the main A418 road between Aylesbury and Leighton Buzzard...

(Bucks.), LinsladeLinsladeLinslade is an English town, located on the Bedfordshire side of the Bedfordshire-Buckinghamshire border . It abuts onto the town of Leighton Buzzard with which it forms the civil parish of Leighton-Linslade. Linslade was transferred from Buckinghamshire in 1965, and was previously a separate...

(Bucks., cf: S 737), HavershamHavershamHaversham is a village in the Borough of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. It is situated just north of Milton Keynes near Wolverton and lies between Newport Pagnell and Stony Stratford. Haversham-cum-Little Linford is a civil parish in the Borough of Milton Keynes.The village has two...

(Bucks.), HatfieldHatfield, HertfordshireHatfield is a town and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England in the borough of Welwyn Hatfield. It has a population of 29,616, and is of Saxon origin. Hatfield House, the home of the Marquess of Salisbury, is the nucleus of the old town...

(Herts.?), Masworth or MarsworthMarsworthMarsworth is a village and also a civil parish within Aylesbury Vale district in Buckinghamshire, England. It is about two miles north of Tring, in Hertfordshire and six miles east of Aylesbury.-Early history:...

(Bucks.) and GussageGussageGussage is a series of three villages in north Dorset, England, situated along a tributary of the River Allen on Cranborne Chase, eight miles north east of Blandford Forum and 10 miles north of Wimborne. The stream runs through all three parishes: Gussage All Saints, population 192, Gussage St...

(All Saints, Dorset)+ 2 armlets (of 120 mancuses each), a drinking-cup (sopcuppan), 6 horses, 6 shields and spears (presumably her heriot HeriotHeriot, from Old English heregeat , was originally a death-duty in late Anglo-Saxon England, which required that at death, a nobleman provided to his king a given set of military equipment, often including horses, swords, shields, spears and helmets...

"death-duty").the ætheling, probably Edward Edward the MartyrEdward the Martyr was king of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar, but not his father's acknowledged heir...estate at Newnham Murren Newnham MurrenNewnham Murren is a village in the Thames Valley in South Oxfordshire, about east of the market town of Wallingford. Newnham Murren is in the civil parish of Crowmarsh and is now contiguous with the village of Crowmarsh Gifford.-History:...

(Oxon.), previously granted by King Edgar (S 738)+ armlet of 30 mancuses Queen (Ælfthryth) a necklace of 120 mancuses, armlet of 30 mancuses, and a drinking-cup Family Ælfweard, Æthelweard and Ælfwaru estates at Mongewell MongewellMongewell is a village in the civil parish of Crowmarsh, about south of Wallingford in Oxfordshire. Mongewell is on the east bank of the Thames, linked with the west bank at Winterbrook by the nearby Winterbrook Bridge...

(Oxon.) and Berkhampstead (Herts.) for their lifetime, with annual food-rent of two days for the Old and New Minster; with reversion to the Old Minster after their life-time.Ælfwaru "all that I have lent her" Ælfweard drinking-cup Æthelweard ornamented drinking-horn Æthelflæd, her brother's wife headband Bishops and abbots Bishop Æthelwold estate at Tæafersceat (unidentified), with a request to intercede for her and her mother. Each abbot 5 pounds of pence to spend on repairing their minster Bishop Æthelwold and Æthelgar ÆthelgarÆthelgar was Archbishop of Canterbury, and previously Bishop of Selsey.-Biography:Æthelgar was a monk at Glastonbury Abbey before he was the discipulus of Aethelwold the Bishop of Winchester. He then continued as a monk at Abingdon Abbey, until 964 when he was appointed Abbot of the newly reformed...

, abbot of the New Minster.remaining money entrusted to them for (1) maintenance of the Old Minster and (2) alms-giving.

----

Primary sources

- Æthelweard, The Chronicle of Aethelweard: Chronicon Aethelweardi, ed. and tr. Alistair Campbell, The Chronicle of Æthelweard. London: Nelson, 1962.

- Anglo-Saxon chartersAnglo-Saxon ChartersAnglo-Saxon charters are documents from the early medieval period in Britain which typically make a grant of land or record a privilege. The earliest surviving charters were drawn up in the 670s; the oldest surviving charters granted land to the Church, but from the eighth century surviving...

:- S 1292, Agreement between Bishop Brihthelm and Æthelwold (AD 956 x 957).

- S 1484, Ælfgifu's will (AD 966 x 975), from the Old Minster archive, ed. and tr. D. Whitelock, Anglo-Saxon Wills. Cambridge Studies in English Legal History. Cambridge, 1930.

- S 737, King Edgar grants 10 hides at LinsladeLinsladeLinslade is an English town, located on the Bedfordshire side of the Bedfordshire-Buckinghamshire border . It abuts onto the town of Leighton Buzzard with which it forms the civil parish of Leighton-Linslade. Linslade was transferred from Buckinghamshire in 1965, and was previously a separate...

(Buckinghamshire) to the matrona Ælfgifu, his kinswoman (AD 966, archive: Abingdon). - S 738, King Edgar to 10 hides at Newnham MurrenNewnham MurrenNewnham Murren is a village in the Thames Valley in South Oxfordshire, about east of the market town of Wallingford. Newnham Murren is in the civil parish of Crowmarsh and is now contiguous with the village of Crowmarsh Gifford.-History:...

(Oxfordshire) to the matrona Ælfgifu, his kinswoman (AD 966, archive: Old Minster). - S 745, New Minster refoundation charter (AD 966).

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle MS D, ed. David Dumville and Simon Keynes, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. a collaborative edition. Vol. 6. Cambridge, 1983

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles; Michael J. Swanton, trans. 2nd ed. London, 2000.

- Author 'B.', Vita S. Dunstani, ed. W. Stubbs, Memorials of St Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. (Rolls Series; 63.) London: Longman & Co., 1874. 3-52.

- Byrhtferth of Ramsey, Life of St Oswald, ed. J. Raine, Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops. (Rolls Series; 71.) 3 vols: vol 1. London: Longman & Co., 1879: 399-475.

- Liber Eliensis, ed. E. O. Blake, Liber Eliensis. (Camden Third Series; 92.) London: Royal Historical Society, 1962; tr. J. Fairweather. Liber Eliensis. A History of the Isle of Ely from the Seventh Century to the Twelfth. Woodbridge, 2005.

- New Minster Liber Vitae, per entries in PASE.

Further reading

- Smythe, Ross Woodward. "Did King Eadwig really abandon his coronation feast to have a ménage à trois with his wife and mother-in-law? What’s the story behind this story?." Quaestio insularis 6 (2005): 82-97.

- Stafford, Pauline. Unification and conquest. A political and social history of England in the tenth and eleventh centuries. London, 1989.