Divisionism

Encyclopedia

Neo-impressionism

Neo-impressionism was coined by French art critic Félix Fénéon in 1886 to describe an art movement founded by Georges Seurat. Seurat’s greatest masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, marked the beginning of this movement when it first made its appearance at an exhibition...

painting defined by the separation of colors into individual dots or patches which interacted optically.

By requiring the viewer to combine the colors optically instead of physically mixing pigments, divisionists believed they were achieving the maximum luminosity

Luminosity

Luminosity is a measurement of brightness.-In photometry and color imaging:In photometry, luminosity is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to luminance, which is the density of luminous intensity in a given direction. The SI unit for luminance is candela per square metre.The luminosity function...

scientifically possible. Georges Seurat founded the style around 1884 as chromoluminarism, drawing from his understanding of the scientific theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul

Michel Eugène Chevreul

Michel Eugène Chevreul was a French chemist whose work with fatty acids led to early applications in the fields of art and science. He is credited with the discovery of margaric acid and designing an early form of soap made from animal fats and salt...

, Ogden Rood

Ogden Rood

Ogden Nicholas Rood was an American physicist best known for his work in color theory. He studied in Berlin and Munich before his appointment as Chair of Physics at Columbia University, a position he held from 1863 until his death...

and Charles Blanc

Charles Blanc

Charles Blanc was a French art critic, brother of Louis Blanc. After the February Revolution of 1848, he was director of the department for the visual arts at the ministry of the interior...

, among others. Divisionism developed along with another style, pointillism

Pointillism

Pointillism is a technique of painting in which small, distinct dots of pure color are applied in patterns to form an image. Georges Seurat developed the technique in 1886, branching from Impressionism. The term Pointillism was first coined by art critics in the late 1880s to ridicule the works...

, which is defined specifically by the use of dots of paint and does not necessarily focus on the separation of colors.

Theoretical foundations and development

Divisionism developed in nineteenth century painting as artists discovered scientific theories of vision which encouraged a departure from the tenets of ImpressionismImpressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement that originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s...

, which at that point had been well-developed. The scientific theories and rules of color contrast that would guide composition for divisionists placed the movement of Neo-Impressionism in contrast with Impressionism, which is characterized by the use instinct and intuition. Scientists or artists whose theories of light or color had some impact on the development of divisionism include Charles Henry, Charles Blanc

Charles Blanc

Charles Blanc was a French art critic, brother of Louis Blanc. After the February Revolution of 1848, he was director of the department for the visual arts at the ministry of the interior...

, David Pierre Giottino Humbert de Superville

David Pierre Giottino Humbert de Superville

David Pierre Giottino Humbert de Superville was a Dutch artist and art scholar. He was a draughtsman, lithographer, etcher, and portrait painter, and also wrote treatises on art, including the influential work Essai sur les signes inconditionnels dans l'art...

, David Sutter, Michel Eugène Chevreul

Michel Eugène Chevreul

Michel Eugène Chevreul was a French chemist whose work with fatty acids led to early applications in the fields of art and science. He is credited with the discovery of margaric acid and designing an early form of soap made from animal fats and salt...

, Ogden Rood

Ogden Rood

Ogden Nicholas Rood was an American physicist best known for his work in color theory. He studied in Berlin and Munich before his appointment as Chair of Physics at Columbia University, a position he held from 1863 until his death...

and Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz was a German physician and physicist who made significant contributions to several widely varied areas of modern science...

.

Beginnings with Georges Seurat

Divisionism, along with the Neo-Impressionism movement as a whole, found its beginnings in Georges Seurat's masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Seurat was classically trained in the École des Beaux-ArtsÉcole des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts refers to a number of influential art schools in France. The most famous is the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, now located on the left bank in Paris, across the Seine from the Louvre, in the 6th arrondissement. The school has a history spanning more than 350 years,...

, and, as such, his initial works reflected the Barbizon

Barbizon

Barbizon is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in north-central France. It is located near the Fontainebleau Forest.-Art history:The Barbizon school of painters is named after the village; Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet, leaders of the school, made their homes and died in the...

style. In 1883, Seurat and some of his colleagues began exploring ways to express as much light as possible on the canvas

. By 1884, with the exhibition of his first major work, Bathing at Asnières, as well as croquetons of the island of La Grande Jatte, his style began taking form with an awareness of Impressionism, but it was not until he finished La Grande Jatte in 1886 that he established his theory of chromoluminarism. In fact, La Grande Jatte was not initially painted in the divisionist style, but he reworked the painting in the winter of 1885-6, enhancing its optical properties in accordance with his interpretation of scientific theories of color and light

.

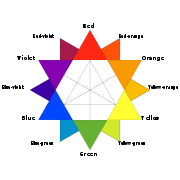

Color theory

Charles Blanc's Grammaire des arts du dessin introduced Seurat to the theories of color and vision that would inspire chromoluminarism. Blanc's work, drawing from the theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Eugène DelacroixEugène Delacroix

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix was a French Romantic artist regarded from the outset of his career as the leader of the French Romantic school...

, stated that optical mixing would produce more vibrant and pure colors than the traditional process of mixing pigments. Mixing pigments physically is a subtractive process

Subtractive color

A subtractive color model explains the mixing of paints, dyes, inks, and natural colorants to create a full range of colors, each caused by subtracting some wavelengths of light and reflecting the others...

with cyan, magenta, and yellow being the primary colors

Primary Colors

Primary Colors: A Novel of Politics is a roman à clef, a work of fiction that purports to describe real life characters and events — namely, Bill Clinton's first presidential campaign in 1992...

. On the other hand, if colored light is mixed together, an additive mixture

Additive color

An additive color model involves light emitted directly from a source or illuminant of some sort. The additive reproduction process usually uses red, green and blue light to produce the other colors. Combining one of these additive primary colors with another in equal amounts produces the...

results, a process in which the primary colors are red, green and blue. The optical mixture which characterized divisionism — the process of mixing color by juxtaposing pigments — is different from either additive or subtractive mixture, although combining colors in optical mixture functions the same way as additive mixture, i.e. the primary colors are the same. In reality, Seurat's paintings did not actually achieve true optical mixing; for him, the theory was more useful for causing vibrations of color to the viewer, where contrasting colors placed near each other would intensify the relationship between the colors while preserving their singular separate identity.

In divisionist color theory, artists interpreted the scientific literature through making light operate in one of the following contexts:

- Local color: As the dominant element of the painting, local color refers to the true color of subjects, e.g. green grass or blue sky.

- Direct sunlight: As appropriate, yellow-orange colors representing the sun’s action would be interspersed with the natural colors to emulate the effect of direct sunlight.

- Shadow: If lighting is only indirect, various other colors, such as blues, reds and purples, can be used to simulate the darkness and shadows.

- Reflected light: An object which is adjacent to another in a painting could cast reflected colors onto it.

- Contrast: To take advantage of Chevreul’s theory of simultaneous contrast, contrasting colors might be placed in close proximity.

Paul Signac and other artists

Seurat’s theories intrigued many of his contemporaries, as other artists seeking a reaction against Impressionism joined the Neo-Impressionist movement. Paul SignacPaul Signac

Paul Signac was a French neo-impressionist painter who, working with Georges Seurat, helped develop the pointillist style.-Biography:Paul Victor Jules Signac was born in Paris on 11 November 1863...

, in particular, became one of the main proponents of divisionist theory, especially after Seurat’s death in 1891. In fact, Signac’s book, D’Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme, published in 1899, coined the term divisionism and became widely recognized as the manifesto of Neo-Impressionism.

In addition to Signac, other French artists, largely through associations in the Société des Artistes Indépendants

Société des Artistes Indépendants

—The Société des Artistes Indépendants formed in Paris in summer 1884 choosing the device "No jury nor awards" . Albert Dubois-Pillet, Odilon Redon, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac were among its founders...

, adopted some divisionist techniques, including Camille

Camille Pissarro

Camille Pissarro was a French Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painter born on the island of St Thomas . His importance resides in his contributions to both Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as he was the only artist to exhibit in both forms...

and Lucien Pissarro

Lucien Pissarro

Lucien Pissarro was a landscape painter, printmaker, wood engraver and designer and printer of fine books. His landscape paintings employ techniques of Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism, but he also exhibited with Les XX. Apart from his landscapes he painted only a few still-lifes and family...

, Albert Dubois-Pillet

Albert Dubois-Pillet

Albert Dubois-Pillet , was a French painter and army officer.He graduated from the École Impériale Militaire at Saint-Cyr in 1867, and fought the Franco-Prussian War, during which he was made prisoner by the Germans...

, Charles Angrand

Charles Angrand

Charles Angrand was a French artist who gained renown for his Neo-Impressionist paintings and drawings. He was an important member of the Parisian avant-garde art scene in the late 1880s and early 1890s.-Early life and work:...

, Maximilien Luce

Maximilien Luce

Maximilien Luce was a French Neo-impressionist artist. A printmaker, painter, and anarchist, Luce is best known for his pointillist canvases. He grew up in the working class Montparnasse, and became a painter of landscapes and urban scenes which frequently emphasize the activities of people at work...

, Henri-Edmond Cross

Henri-Edmond Cross

Henri-Edmond Cross was a French pointillist painter.- Life and career :Cross was born in Douai and grew up in Lille. He studied at the École des Beaux-Arts. His early works, portraits and still lifes, were in the dark colors of realism, but after meeting with Claude Monet in 1883, he painted in...

and Hippolyte Petitjean. Additionally, through Paul Signac’s advocacy of divisionism, an influence can be seen in some of the works of Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh , and used Brabant dialect in his writing; it is therefore likely that he himself pronounced his name with a Brabant accent: , with a voiced V and palatalized G and gh. In France, where much of his work was produced, it is...

, Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse was a French artist, known for his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsmanship. He was a draughtsman, printmaker, and sculptor, but is known primarily as a painter...

, Robert Delaunay

Robert Delaunay

Robert Delaunay was a French artist who, with his wife Sonia Delaunay and others, cofounded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes. His later works were more abstract, reminiscent of Paul Klee...

and Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

.

In Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, artists of the futurist movement who read Signac’s book also took up divisionist techniques as part of a separate Italian Divisionism movement. This movement either characterized or influenced the work of many Italian artists, including Vitorio Grubicy, Angelo Morbelli

Angelo Morbelli

Angelo Morbelli was an Italian painter.-Biography:A grant from the City Council of Alessandria enabled Morbelli to enrol at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts, Milan, in 1867. He was awarded the Fumagalli Prize at the Brera exhibition of 1883 for Last Days as well as a gold medal at the Paris...

, Giovanni Segantini

Giovanni Segantini

Giovanni Segantini was an Italian painter known for his large pastoral landscapes of the Alps. He was one of the most famous artists in Europe in the late 19th century, and his paintings were collected by major museums. In later life he combined a Divisionist painting style with Symbolist images...

, Emilio Longoni

Emilio Longoni

Emilio Longoni was an Italian painter.-Biography:He was born in Barlassina on July 9, 1859, fourth of twelve children, from Garibaldi’s volunteer and horseshoer Matteo Longoni and from tailor Luigia Meroni....

, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo was an Italian painter. He was born and died in Volpedo, in the Piedmont region of northern Italy....

, Gaetano Previati

Gaetano Previati

Gaetano Previati was an Italian painter.-Biography:Previati moved from Ferrara to Milan in 1876 and enrolled at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts, winning the Canonica competition in 1879. Having settled in Milan definitively in 1881, he came into contact with the Scapigliatura movement...

, Plino Nomelli, Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni was an Italian painter and sculptor. Like other Futurists, his work centered on the portrayal of movement , speed, and technology. He was born in Reggio Calabria, Italy.-Biography:...

, Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla

Giacomo Balla was an Italian painter.-Biography:Born in Turin, in the Piedmont region of Italy, the son of an industrial chemist, as a child Giacomo Balla studied music....

, Carlo Carrà

Carlo Carrà

Carlo Carrà was an Italian painter, a leading figure of the Futurist movement that flourished in Italy during the beginning of the 20th century. In addition to his many paintings, he wrote a number of books concerning art. He taught for many years in the city of Milan.-Biography:Carrà was born in...

and Gino Severini

Gino Severini

Gino Severini , was an Italian painter and a leading member of the Futurist movement. For much of his life he divided his time between Paris and Rome. He was associated with neo-classicism and the "return to order" in the decade after the First World War. During his career he worked in a variety of...

.

Criticism and controversy

Divisionism quickly received both negative and positive attention from art critics, who generally either embraced or condemned the incorporation of scientific theories in the Neo-Impressionist techniques. For example, one critic, Joris-Karl HuysmansJoris-Karl Huysmans

Charles-Marie-Georges Huysmans was a French novelist who published his works as Joris-Karl Huysmans . He is most famous for the novel À rebours...

, spoke negatively of Seurat’s paintings, saying “Strip his figures of the colored fleas that cover them, underneath there is nothing, no thought, no soul, nothing” . Leaders of Impressionism, such as Monet and Renoir

Renoir

-People with the surname Renoir :* Pierre-Auguste Renoir , French painter* Pierre Renoir , French actor and son of Pierre-Auguste Renoir* Jean Renoir , French film director and son of Pierre-Auguste Renoir...

, refused to exhibit with Seurat, and even Camille Pissarro, who initially supported divisionism, spoke negatively of the technique eventually.

While most divisionists did not receive much critical approval for the majority of their careers, some critics were loyal to the movement, including most notably Félix Fénéon

Félix Fénéon

Félix Fénéon was a Parisian anarchist and art critic during the late 19th century...

, Arsène Alexandre and Antoine de la Rochefoucauld

Antoine de La Rochefoucauld

Count Antoine de La Rochefoucauld was an artist, patron and art collector as well as a proponent of Rosicrucianism in France at the end of the 19th century.-Life:...

.

Scientific misconceptions

Although divisionist artists strongly believed their style was founded in scientific principles, some people believe that there is evidence that divisionists misinterpreted some basic elements of optical theory. For example, one of these misconceptions can be seen in the general belief that the divisionist method of painting allowed for greater luminosity than previous techniques. Additive luminosity is only applicable in the case of colored light, not juxtaposed pigments; in reality, the luminosity of two pigments next to each other is just the average of their individual luminosities. Furthermore, it is not possible to create a color using optical mixture which could not also be created by physical mixture. Logical inconsistencies can also be found with the divisionist exclusion of darker colors and their interpretation of simultaneous contrast.Further reading

- Blanc, Charles. The Grammar of Painting and Engraving. Chicago: S.C. Griggs and Company, 1891. http://www.archive.org/download/grammarofpaintin00blaniala/grammarofpaintin00blaniala.pdf.

- Block, Jane. "Neo-Impressionism." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T061684.

- Block, Jane. "Pointillism." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T068278.

- Broude, Norma, ed. Seurat in Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978. ISBN 0138071152.

- Cachin, Françoise. Paul Signac. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1971. ISBN 0821204823.

- Clement, Russell T., and Annick Houzé. Neo-impressionist painters: a sourcebook on Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Henri Edmond Cross, Charles Angrand, Maximilien Luce, and Albert Dubois-Pillet. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1999. ISBN 0313303827.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène. The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1860. http://books.google.com/books?id=LIMOAAAAQAAJ.

- Gage, John. "The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal." The Art Bulletin 69 (Sep. 1987): 448-54. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3051065.

- Herbert, Robert L. Neo-Impressionism. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1968.

- Hutton, John G. Neo-impressionism and the search for solid ground: art, science, and anarchism in fin-de-siècle France. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State UP, 1994. ISBN 0807118230.

- Rewald, John. Georges Seurat. New York: Wittenborn & Co., 1946.

- Signac, Paul. D’Eugène Delacroix au Neo-Impressionnisme. 1899. http://www.archive.org/download/deugnedelacroi00signuoft/deugnedelacroi00signuoft.pdf.

- Winkfield, Trevor. "The Signac Syndrome." Modern Painters Autumn 2001: 66-70.

- Tim Parks on divisionist movement of painters in Italy