Treaty of Pereyaslav

Encyclopedia

The Treaty of Pereyaslav is known in history more as the Council of Pereiaslav.

Council of Pereyalslav was a meeting between the representative of the Russian Tsar, Prince Vasili Baturlin who presented a royal decree, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky

as the leader of Cossack Hetmanate

. During the council Bohdan Khmelnytsky

with his troops accepted the allegiance of the Tsardom of Russia. The document itself, also known as the March Articles and Articles of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, for unknown reasons has not survived.

with petition for a military alliance. To review the petition on October 1, 1653 a council was gathered in the Palace of Facets

(Pomegranate Chamber) consisting of Patriarch of Moscow Nikon

with various other clergy, boyar

s, okolnichy

, noblemen, and others. The decision of the Council was declared on October 4 in the Golden Chamber

of Kremlin Palace. The Hetman's ambassadors were informed that Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich satisfies the petition of the Zaporizhian Host and accepts the alliance.

To the Zaporizhian Host was sent the Russian delegation that included such major figures as boyars Vasiliy Buturlin and Ivan Alferyev, and dyak

Larion Lopukhin. Among other members there was prince Grigoriy Romodanovskiy. For protection along with the delegation was sent a riflemen prikaz

of Artamon Matveyev.

Participants in the preparation of the treaty at Pereyaslav included Hetman

, Bohdan Khmelnytsky

, and numerous Cossacks pledged alliance with the Russian Crown on January 8, 1654 in the Cathedral of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary in Pereyaslav. After that several cities that subordinated to the Hetman pledged their alliance as well (some 166 cities). At the Pereyaslav council were formulated the articles of the treaty and a new delegation was sent to Moscow with a military judge Samoilo Bohdanovych and the Pereiaslav Colonel Pavlo Teteria

.

Eleven articles of Bohdan Khmelnytsky were delivered to Moscow on March 12, 1654. The next day the delegation was met in the Kremlin Armoury

by Vasiliy Buturlin, okolnichy Pyotr Golovin, and the Duma clerk Almaz Ivanov

. Some additional articles were received vocally and were requested to be annotated.

The original copies of the treaty did not survive, and the exact nature of the relationship stipulated by this treaty between Ukraine

and Russia is a matter of scholarly controversy. The treaty led to the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate

in left-bank Ukraine

, and to the outbreak of the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667).

The outcome of the treaty differed from Khmelnytsky's intentions; originally a political manoeuvre intended only to secure the support of powerful allies, it revealed the full extent of its far-reaching consequences over time. Major results of the treaty included the separation of Ukraine from formerly dominant Catholic Poland

The outcome of the treaty differed from Khmelnytsky's intentions; originally a political manoeuvre intended only to secure the support of powerful allies, it revealed the full extent of its far-reaching consequences over time. Major results of the treaty included the separation of Ukraine from formerly dominant Catholic Poland

, the re-strengthening of Orthodoxy

in the historic center of Ukraine, and the eventual domination of Ukraine by neighboring Orthodox Russia

, with Ukrainian clergy dominating the church.

In the long run, the consequences for Ukraine were pivotal. Polish colonization and Polonization

of the upper class soon became replaced by a systematic process of Russification

, culminating in the Ems Ukaz

of 1876, which restricted the printing of books in Ukrainian language

. Further consequences included the disbandment of the Zaporizhian Host and reinstating serfdom in Ukraine.

For Russia

For Russia

, the treaty eventually led to the acquisition of Ukraine, providing a justification for the ambitious title of Russian tsars and emperors, The Ruler of All Rus’. Russia, being at that time the only part of the former Kievan Rus'

which was not occupied by a foreign power, considered itself as legitimate successor and reunificator of former Rus' lands.

For Poland, the treaty provided one of the early signs of its gradual decline and eventual demise

by the end of the 18th century.

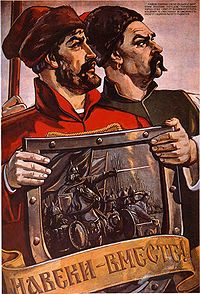

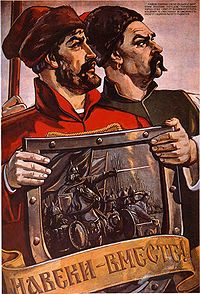

This treaty is seen by Ukrainian nationalists as a sad occasion of the lost chance for Ukrainian independence. The "Rainbow" monument

in the Ukrainian capital Kiev

being colloquially referred to as "Yoke

of the Peoples" further demonstrates the controversial nature of the treaty. Pro-Russian Ukrainian parties, on the other hand, celebrate the date of this event and renew calls for the re-unification of the three Eastern Slavic nations: Russia

, Ukraine

and Belarus

.

In 2004, after the celebration of the 350th anniversary of the event, the administration of president Leonid Kuchma

of Ukraine established January 18 as the official date to commemorate the event, a move which created controversy. Previously, in 1954, the anniversary celebrations included the transfer of Crimea

from the Russian Republic to the Ukrainian Republic

of the Soviet Union

.

Council of Pereyalslav was a meeting between the representative of the Russian Tsar, Prince Vasili Baturlin who presented a royal decree, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

as the leader of Cossack Hetmanate

Cossack Hetmanate

The Hetmanate or Zaporizhian Host was the Ruthenian Cossack state in the Central Ukraine between 1649 and 1782.The Hetmanate was founded by first Ukrainian hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky during the Khmelnytsky Uprising . In 1654 it pledged its allegiance to Muscovy during the Council of Pereyaslav,...

. During the council Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

with his troops accepted the allegiance of the Tsardom of Russia. The document itself, also known as the March Articles and Articles of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, for unknown reasons has not survived.

History

In 1653 Bohdan Khmelnytsky sent a diplomatic delegation which included his military starshyna Hryhoriy Huletsky and his secretary-general (pysar) Ivan VyhovskyIvan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky was a hetman of the Ukrainian Cossacks during three years of the Russo-Polish War . He was the successor to the famous hetman and rebel leader Bohdan Khmelnytsky...

with petition for a military alliance. To review the petition on October 1, 1653 a council was gathered in the Palace of Facets

Palace of Facets

The Palace of the Facets is a building in the Moscow Kremlin, Russia, which contains what used to be the main banquet reception hall of the Muscovite Tsars. It is the oldest preserved secular building in Moscow. Located on Kremlin Cathedral Square, between the Cathedral of the Annunciation and the...

(Pomegranate Chamber) consisting of Patriarch of Moscow Nikon

Patriarch Nikon

Nikon , born Nikita Minin , was the seventh patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church...

with various other clergy, boyar

Boyar

A boyar, or bolyar , was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian, Kievan Rus'ian, Bulgarian, Wallachian, and Moldavian aristocracies, second only to the ruling princes , from the 10th century through the 17th century....

s, okolnichy

Okolnichy

Okolnichy was an old rank and a position at the court of Moscow rulers from the Mongol invasion of Rus' until the government reform undertaken by Peter the Great...

, noblemen, and others. The decision of the Council was declared on October 4 in the Golden Chamber

Tsarina Golden Palace

The Tsarina's Golden Chamber , is the official reception room of the Russian tsarinas, where they held formal celebrations of Russian monarchs' weddings, meetings with Russian and foreign clergy, and receptions for relatives of the royal family and for ladies of the court. It is part of the tsar's...

of Kremlin Palace. The Hetman's ambassadors were informed that Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich satisfies the petition of the Zaporizhian Host and accepts the alliance.

To the Zaporizhian Host was sent the Russian delegation that included such major figures as boyars Vasiliy Buturlin and Ivan Alferyev, and dyak

Dyak

Dyak may refer to one of the following.*Dayak people, also called "Dyak", a native tribe of Borneo*Dyak a historical position of head of office in Russia...

Larion Lopukhin. Among other members there was prince Grigoriy Romodanovskiy. For protection along with the delegation was sent a riflemen prikaz

Prikaz

Prikaz was an administrative or judicial office in Muscovy and Russia of 15th-18th centuries. The term is usually translated as "ministry", "office" or "department". In modern Russian "prikaz" means administrative or military order...

of Artamon Matveyev.

Participants in the preparation of the treaty at Pereyaslav included Hetman

Hetman

Hetman was the title of the second-highest military commander in 15th- to 18th-century Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which together, from 1569 to 1795, comprised the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, or Rzeczpospolita....

, Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynoviy Mykhailovych Khmelnytsky was a hetman of the Zaporozhian Cossack Hetmanate of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth . He led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates which resulted in the creation of a Cossack state...

, and numerous Cossacks pledged alliance with the Russian Crown on January 8, 1654 in the Cathedral of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary in Pereyaslav. After that several cities that subordinated to the Hetman pledged their alliance as well (some 166 cities). At the Pereyaslav council were formulated the articles of the treaty and a new delegation was sent to Moscow with a military judge Samoilo Bohdanovych and the Pereiaslav Colonel Pavlo Teteria

Pavlo Teteria

Pavlo Teteria was Hetman of Right-Bank Ukraine .Before his hetmancy he served in a number of high positions under Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and Ivan Vyhovsky....

.

Eleven articles of Bohdan Khmelnytsky were delivered to Moscow on March 12, 1654. The next day the delegation was met in the Kremlin Armoury

Kremlin Armoury

The Kremlin Armory is one of the oldest museums of Moscow, established in 1808 and located in the Moscow Kremlin .The Kremlin Armoury originated as the royal arsenal in 1508. Until the transfer of the court to St Petersburg, the Armoury was in charge of producing, purchasing and storing weapons,...

by Vasiliy Buturlin, okolnichy Pyotr Golovin, and the Duma clerk Almaz Ivanov

Almaz Ivanov

Almaz Ivanovich Ivanov was a Russian statesman.From 1640 to 1646, Almaz Ivanov held the post of a dyak of the royal treasury . In 1646, he was transferred to the Posolsky Prikaz...

. Some additional articles were received vocally and were requested to be annotated.

The original copies of the treaty did not survive, and the exact nature of the relationship stipulated by this treaty between Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

and Russia is a matter of scholarly controversy. The treaty led to the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate

Cossack Hetmanate

The Hetmanate or Zaporizhian Host was the Ruthenian Cossack state in the Central Ukraine between 1649 and 1782.The Hetmanate was founded by first Ukrainian hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky during the Khmelnytsky Uprising . In 1654 it pledged its allegiance to Muscovy during the Council of Pereyaslav,...

in left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine is a historic name of the part of Ukraine on the left bank of the Dnieper River, comprising the modern-day oblasts of Chernihiv, Poltava and Sumy as well as the eastern parts of the Kiev and Cherkasy....

, and to the outbreak of the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667).

Historical consequences

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a dualistic state of Poland and Lithuania ruled by a common monarch. It was the largest and one of the most populous countries of 16th- and 17th‑century Europe with some and a multi-ethnic population of 11 million at its peak in the early 17th century...

, the re-strengthening of Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

in the historic center of Ukraine, and the eventual domination of Ukraine by neighboring Orthodox Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, with Ukrainian clergy dominating the church.

In the long run, the consequences for Ukraine were pivotal. Polish colonization and Polonization

Polonization

Polonization was the acquisition or imposition of elements of Polish culture, in particular, Polish language, as experienced in some historic periods by non-Polish populations of territories controlled or substantially influenced by Poland...

of the upper class soon became replaced by a systematic process of Russification

Russification

Russification is an adoption of the Russian language or some other Russian attributes by non-Russian communities...

, culminating in the Ems Ukaz

Ems Ukaz

The Ems Ukaz, or Ems Ukase , was a secret decree of Tsar Alexander II of Russia issued in 1876, banning the use of the Ukrainian language in print, with the exception of reprinting of old documents. The ukaz also forbade the import of Ukrainian publications and the staging of plays or lectures in...

of 1876, which restricted the printing of books in Ukrainian language

Ukrainian language

Ukrainian is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet....

. Further consequences included the disbandment of the Zaporizhian Host and reinstating serfdom in Ukraine.

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, the treaty eventually led to the acquisition of Ukraine, providing a justification for the ambitious title of Russian tsars and emperors, The Ruler of All Rus’. Russia, being at that time the only part of the former Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rus was a medieval polity in Eastern Europe, from the late 9th to the mid 13th century, when it disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of 1237–1240....

which was not occupied by a foreign power, considered itself as legitimate successor and reunificator of former Rus' lands.

For Poland, the treaty provided one of the early signs of its gradual decline and eventual demise

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

by the end of the 18th century.

This treaty is seen by Ukrainian nationalists as a sad occasion of the lost chance for Ukrainian independence. The "Rainbow" monument

People's Friendship Arch

The People’s Friendship Arch dedicated to the unification of Russia and Ukraine, was constructed in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine.The Friendship Arch was constructed in 1982 by sculptor A. Skoblikov and architect I. Ivanov and others...

in the Ukrainian capital Kiev

Kiev

Kiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

being colloquially referred to as "Yoke

Yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam, normally used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, used in different cultures, and for different types of oxen...

of the Peoples" further demonstrates the controversial nature of the treaty. Pro-Russian Ukrainian parties, on the other hand, celebrate the date of this event and renew calls for the re-unification of the three Eastern Slavic nations: Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

and Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

.

In 2004, after the celebration of the 350th anniversary of the event, the administration of president Leonid Kuchma

Leonid Kuchma

Leonid Danylovych Kuchma was the second President of independent Ukraine from 19 July 1994, to 23 January 2005. Kuchma took office after winning the 1994 presidential election against his rival, incumbent Leonid Kravchuk...

of Ukraine established January 18 as the official date to commemorate the event, a move which created controversy. Previously, in 1954, the anniversary celebrations included the transfer of Crimea

Crimea

Crimea , or the Autonomous Republic of Crimea , is a sub-national unit, an autonomous republic, of Ukraine. It is located on the northern coast of the Black Sea, occupying a peninsula of the same name...

from the Russian Republic to the Ukrainian Republic

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

.

Printed

- Hrushevs’kyi, M. Istoriia Ukraïny-Rusy, vol 9, bk 1 (Kiev 1928; New York 1957)

- Iakovliv, A. Ukraïns’ko-moskovs’ki dohovory v XVII–XVIII vikakh (Warsaw 1934)

- Dohovir het’mana Bohdana Khmel’nyts’koho z moskovs’kym tsarem Oleksiiem Mykhailovychem (New York 1954)

- Ohloblyn, A. Treaty of Pereyaslav 1654 (Toronto and New York 1954)

- Prokopovych, V. ‘The Problem of the Juridical Nature of the Ukraine's Union with Muscovy,’ AUA, 4 (Winter–Spring 1955)

- O'Brien, C.B. Muscovy and the Ukraine: From the Pereiaslavl Agreement to the Truce of Andrusovo, 1654–1667 (Berkeley and Los Angeles 1963)

- Braichevsky, M. Annexation or Unification?: Critical Notes on One Conception, ed and trans G. Kulchycky (Munich 1974)

- Basarab, J. Pereiaslav 1654: A Historiographical Study (Edmonton 1982) http://www.utoronto.ca/cius/publications/books/pereiaslav.htm

- Pereiaslavs'ka rada 1654 roku. Istoriohrafiia ta doslidzhennia (Kiev 2003) http://www.utoronto.ca/cius/publications/books/pereiaslavskarada.htm

Online

- To the History of the Treaty of Pereyaslav, Zerkalo NedeliZerkalo NedeliZerkalo Nedeli , usually referred to in English as the Mirror Weekly, is one of Ukraine’s most influential analytical newspapers published weekly in Kiev, the nation's capital. It was founded in 1994, and as of 2006 its print circulation was 57,000. It offers political analysis, original...

(the Mirror Weekly), October 4–10, 2003, available online in Russian and in Ukrainian. - Encyclopedia of Ukraine entry on the subject

- Ukrainian World Congress' Statement Press Release - On Observance of the Pereyaslav Treaty

- The Treaty of Pereyaslav

- Pereiaslav Council: myths and reality.