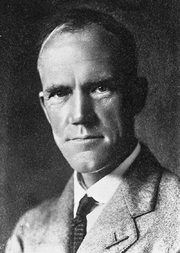

Thomas Griffith Taylor

Encyclopedia

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

/ Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

n geographer

Geographer

A geographer is a scholar whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society.Although geographers are historically known as people who make maps, map making is actually the field of study of cartography, a subset of geography...

, anthropologist and world explorer. He was a survivor of Captain Robert Scott

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, CVO was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13...

's ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition

Terra Nova Expedition

The Terra Nova Expedition , officially the British Antarctic Expedition 1910, was led by Robert Falcon Scott with the objective of being the first to reach the geographical South Pole. Scott and four companions attained the pole on 17 January 1912, to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald...

to Antarctica (1910–1913).

Early life

Walthamstow

Walthamstow is a district of northeast London, England, located in the London Borough of Waltham Forest. It is situated north-east of Charing Cross...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, to parents James Taylor, a metallurgical chemist, and Lily Agnes, née Griffiths. Within a year, the family had moved to Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

where his father was manager of a copper mine. Three years later, they returned to Britain when his father became director of analytical chemistry for a major steelworks company. In 1893, the family emigrated to New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, where James secured a position as a government metallurgist. Taylor, age 13, attended The King's School

The King's School, Sydney

The King's School is an independent Anglican, day and boarding school for boys in North Parramatta in the western suburbs of Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1831, it is Australia's oldest school and forms one of the nine "Great Public Schools" of New South Wales. Situated within a site, Gowan Brae,...

in Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

. He enrolled in arts at the University of Sydney

University of Sydney

The University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

in 1899, later transferring to science, attaining his Bachelor of Science

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science is an undergraduate academic degree awarded for completed courses that generally last three to five years .-Australia:In Australia, the BSc is a 3 year degree, offered from 1st year on...

in 1904, and Bachelor of Engineering

Bachelor of Engineering

The Bachelor of Engineering is an undergraduate academic degree awarded to a student after three to five years of studying engineering at universities in Armenia, Australia, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland , Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Jordan, Korea,...

(mining and metallurgy) in 1905. Awarded an 1851 Exhibition scholarship in 1907 to Emmanuel College, Cambridge (B.A. [Research], 1909), Taylor was elected a fellow of the Geological Society, London in 1909.

While at Cambridge, he established strong friendships with (Sir) Raymond Priestley

Raymond Priestley

Sir Raymond Edward Priestley was a British geologist and early Antarctic explorer.-Biography:Raymond Priestley was born in Bredon's Norton,Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, in 1886, the second son and second of eight children of Joseph Edward Priestley, headmaster of Tewkesbury grammar school, and his...

, Canada's Charles Wright and the Australian Frank Debenham

Frank Debenham

Frank Debenham, OBE was Emeritus Professor of Geography at the Cambridge University and first director of the Scott Polar Research Institute.-Biography:...

who all shared his passion for Antarctic exploration and would all travel with him to the Antarctic as part of the Terra Nova Expedition

Terra Nova Expedition

The Terra Nova Expedition , officially the British Antarctic Expedition 1910, was led by Robert Falcon Scott with the objective of being the first to reach the geographical South Pole. Scott and four companions attained the pole on 17 January 1912, to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald...

1910-1913.

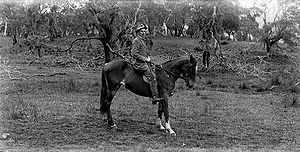

Antarctic Expedition

The explorer Robert Falcon ScottRobert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, CVO was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13...

contracted Taylor to the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition

Terra Nova Expedition

The Terra Nova Expedition , officially the British Antarctic Expedition 1910, was led by Robert Falcon Scott with the objective of being the first to reach the geographical South Pole. Scott and four companions attained the pole on 17 January 1912, to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald...

to Antarctica. Scott was looking for an experienced team, and appointed Taylor as Senior Geologist. It was agreed that Taylor would act as representative for the weather service, due to the known effects of Antarctic weather conditions on Australia's climate.

McMurdo Sound

The ice-clogged waters of Antarctica's McMurdo Sound extend about 55 km long and wide. The sound opens into the Ross Sea to the north. The Royal Society Range rises from sea level to 13,205 feet on the western shoreline. The nearby McMurdo Ice Shelf scribes McMurdo Sound's southern boundary...

, in a region between the McMurdo Dry Valleys

McMurdo Dry Valleys

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are a row of snow-free valleys in Antarctica located within Victoria Land west of McMurdo Sound. The region is one of the world's most extreme deserts, and includes many interesting features including Lake Vida and the Onyx River, Antarctica's longest river.-Climate:The Dry...

and the Koettlitz Glacier

Koettlitz Glacier

The Koettlitz Glacier is a large Antarctic glacier lying west of Mount Morning and Mount Discovery, flowing from the vicinity of Mount Cocks northeastward between Brown Peninsula and the mainland into the ice shelf of McMurdo Sound....

. He led a second successful expedition in November, 1911, this time centring on the Granite Harbour region approximately 50 miles (80 km) north of Butter Point. Meanwhile, Scott led a party of five on a journey to the South Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

, in a race to get there before a rival expedition led by Norwegian Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

. They reached the Pole in January 1912, only to find a tent left there by Amundsen containing a dated message informing them that he had reached the Pole 5 weeks earlier. Scott's entire team perished during the return journey.

Taylor's party was due to be picked up by the Terra Nova supply ship on 15 January 1912, but the ship could not reach them. They waited until 5 February before trekking southward, and were rescued from the ice when they were finally spotted by the ship on 18 February. Taylor left Antarctica in March 1912 on board the Terra Nova, unaware of the fate of Scott's polar party. Geological specimens from both Western Mountains expeditions were retrieved by Terra Nova in January 1913. Later that year, Taylor was awarded the King's Polar medal and made a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

of London.

Taylor's physiographical and geomorphological

Geomorphology

Geomorphology is the scientific study of landforms and the processes that shape them...

Antarctic research earned him a doctorate

Doctorate

A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder to teach in a specific field, A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder...

(D.Sc) from the University of Sydney

University of Sydney

The University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

in 1916. He was made Associate Professor of Geography in 1921 becoming the founding head of the Department of Geography at the university. Taylor did not completely agree with the Australian Government's White Australia policy

White Australia policy

The White Australia policy comprises various historical policies that intentionally restricted "non-white" immigration to Australia. From origins at Federation in 1901, the polices were progressively dismantled between 1949-1973....

, which sought to limit immigrants to whites only. Taylor argued that Australia's agricultural resources were limited, and that this, together with other environmental factors, meant that Australia would not be able to support the population goal of 100 million which some optimistically predicted. Moreover, he claimed that due to climactic factors, the interior of Australia would be best settled by broad-headed Mongoloids who were better adapted to the environment. He was severely criticised as unpatriotic for his views on Australia's future development. A textbook he had written containing these views was banned from schools by the Western Australian education authority. Taylor was a strong exponent of the controversial concept of environmental determinism

Environmental determinism

Environmental determinism, also known as climatic determinism or geographical determinism, is the view that the physical environment, rather than social conditions, determines culture...

with the view that "physical environment determines culture." In 1927, he became the first President of the Geographical Society of New South Wales.

Environment, race, and migration

Taylor wrote many books about the effects of the environment in shaping race. He also wrote extensively about migration of the races. Taylor saw theories that explained the genealogy of races as beginning in Africa and then expanding out through the world and evolving in positive ways as antiquated thinking from the 19th century. In his 1937 book Environment, Race, and Migration, Taylor outlines a theory that the "Mongolian" race is the race truest to their past in the hearth of modern humans: Central Asia. AustraloidAustraloid

The Australoid race is a broad racial classification. The concept originated with a typological method of racial classification. They were described as having dark skin with wavy hair, in the case of Veddoids from South Asia and Aboriginal Australians, or hair ranging from straight to kinky in the...

and Negroid races were the first to branch off during humanity's evolution from the Neanderthal and were racially adapted to live in the world's margins. The Negrito

Negrito

The Negrito are a class of several ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia.Their current populations include 12 Andamanese peoples of the Andaman Islands, six Semang peoples of Malaysia, the Mani of Thailand, and the Aeta, Agta, Ati, and 30 other peoples of the Philippines....

race was never related to Neanderthals, and were thus likely developed more directly from apes. "During the million years of Post-Pliocene" time, humans were forced to migrate during four major migrations related to the expansion of the "Great Ice Sheet." As humans moved to different areas of the world they adapted to the environment they encountered. Taylor openly disagrees with Wegener

Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

's theory of Continental Drift

Continental drift

Continental drift is the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other. The hypothesis that continents 'drift' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596 and was fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912...

, writing that the human races evidently migrated into world's regions separately and over time. They moved out over the world, the world didn't move them. (Note: this was written in a period before knowledge of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

). Taylor links skin pigment to temperature and collects extensive data from the period on geology, topology, meteorology, and anthropology. Taylor saw geography in a synthesizing role between explanations of the physical world and the diffusion and evolution of the human species.

"The fittest tribes evolve and survive in the most stimulating regions; i.e., where living is not so hard as to stunt mental development, and not so easy as to encourage sloth and loss of initiative. The least fit are ultimately crowded out into the deserts, the tropical jungles, or the rugged mountains." pg. 6

In regards to anthropology, Taylor looks at records of hair texture and size, nose size, ear size, cephalic indeces, skin color, and height. He links sexual attraction amongst different races to evolved and diverged cultural preferences for beauty. Taylor comes up with the theory of the "tri-peninsular world", in which the world is divided into three peninsulas descending south from a common point in the Arctic (Americas, Europe and Africa, Asia and Australia). In these peninsulas, Taylor finds climate and race similarities. In regards to racial variation within smaller regions, Taylor offers this passage about Europe's races:

"The Eur-African peninsula is now considered. Here the racial types have been fairly well investigated. We know that the term "European" has no value as an ethnological distinction. Thus the Savoyard of eastern France is akin to the wild tribes of the Pamirs, but not to the primitive peoples of the Dordogne only two hundred miles to the west. The Corsican is much more nearly allied to the Cornishman than to the Italian peoples of the adjacent Alps. In Wales, we are told, there are small groups still essentially allied to Neanderthal

Neanderthal

The Neanderthal is an extinct member of the Homo genus known from Pleistocene specimens found in Europe and parts of western and central Asia...

man." pg. 9

The most suitable parts of the world for habitation are, according to Taylor, in Europe, Western Siberia, the Americas, and Eastern China. These are the places that, if not already overcrowded, are where the world's masses must one day move into. Places least adaptable to European styles of agriculture and settlement are considered by Taylor "useless". In the final section of the book Taylor lays out the possibilities of future expansion of the white race, which he sees as the only race which will expand. Though he voices that no Europeans would wish to extinguish or force native people from their lands, "these primitive people are doomed to extinction..." Whites would eventually settle all "useful lands."

Taylor disagreed with theories that put the Nordic race as the apotheosis of mankind. By his theory, Asiatic races would be the most pure. He gives great accolades to the Chinese race. He links Europe's historical accession in the global sphere to a) command of the seas and b) easy access to plentiful surface coal.

Taylor takes a seemingly contradictory viewpoint by both decrying miscegenation and saying that white Australian women who married Chinese men were OK to do so. Mixing of more advanced races was, ostensibly, acceptable, while miscegenation with more primitive races was to be abhorred.

All citations from this section from the book "Environment, Race, and Migration."

Move to Canada and Return to Australia

In 1929, he accepted a post as Senior Professor of Geography at the University of ChicagoUniversity of Chicago

The University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

. In 1936 he moved to the University of Toronto

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, situated on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institution of higher learning in Upper Canada...

founding the Geography department there. During the 1930s, Taylor was co-editor of the German journal on racial studies Zeitschrift fur Rassenkunde, he felt that American scholars were concerned too little with racial classification, and showed an affinity to the works of Baron von Eickstedt

Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt

Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt was a German physical anthropologist who classified humanity into races.-Racial typology:...

. In 1940 he was elected president of the Association of American Geographers

Association of American Geographers

The Association of American Geographers is a non-profit scientific and educational society founded in 1904 and aimed at advancing the understanding, study, and importance of geography and related fields...

, the first non-American to be elected to the post. Taylor was close to Isaiah Bowman

Isaiah Bowman

Isaiah Bowman, AB, Ph. D. was an American geographer...

who shared similar interests in population and settlement studies. After retiring from his post at the university in 1951, he returned to Sydney. In 1954 he was elected to the Australian Academy of Science

Australian Academy of Science

The Australian Academy of Science was founded in 1954 by a group of distinguished Australians, including Australian Fellows of the Royal Society of London. The first president was Sir Mark Oliphant. The Academy is modelled after the Royal Society and operates under a Royal Charter; as such it is...

, the only geographer to receive this distinction. In 1958 he published his autobiography "Journeyman Taylor", and in 1959 was named the first President of the Institute of Australian Geographers.

Taylor died in the Sydney suburb of Manly

Manly, New South Wales

Manly is a suburb of northern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Manly is located 17 kilometres north-east of the Sydney central business district and is the administrative centre of the local government area of Manly Council, in the Northern Beaches region.-History:Manly was named...

on 5 November 1963, aged 82.

In 1976 he was honoured on a postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

http://www.australianstamp.com/images/large/0011880.jpg and in 2001, an Australian postage stamp commemorated Taylor and fellow explorer Douglas Mawson

Douglas Mawson

Sir Douglas Mawson, OBE, FRS, FAA was an Australian geologist, Antarctic explorer and Academic. Along with Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, and Ernest Shackleton, Mawson was a key expedition leader during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.-Early work:He was appointed geologist to an...

. Taylor was the author of some 20 books and 200 scientific articles.

He was the brother-in-law of fellow Terra Nova expedition members Raymond Priestley

Raymond Priestley

Sir Raymond Edward Priestley was a British geologist and early Antarctic explorer.-Biography:Raymond Priestley was born in Bredon's Norton,Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, in 1886, the second son and second of eight children of Joseph Edward Priestley, headmaster of Tewkesbury grammar school, and his...

and C.S. Wright.