Tartessian language

Encyclopedia

Paleohispanic languages

The Paleohispanic languages were the languages of the pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, excluding languages of foreign colonies, such as Greek in Emporion and Phoenician in Qart Hadast...

of inscriptions in the Southwestern script

Southwest script

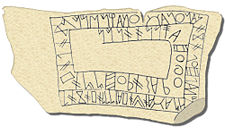

The Southwest Script or Southwestern Script, also known as Tartessian or South Lusitanian, is a Paleohispanic script used to write an unknown language usually identified as Tartessian...

found in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula , sometimes called Iberia, is located in the extreme southwest of Europe and includes the modern-day sovereign states of Spain, Portugal and Andorra, as well as the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar...

: mainly in the south of Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

(Algarve and southern Alentejo), but also in Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

(south of Extremadura

Extremadura

Extremadura is an autonomous community of western Spain whose capital city is Mérida. Its component provinces are Cáceres and Badajoz. It is bordered by Portugal to the west...

and western Andalucia). There are 95 of these inscriptions with the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one-third of them have been found in Early Iron Age necropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them from the 7th century BCE and consider the southwestern script

Southwest script

The Southwest Script or Southwestern Script, also known as Tartessian or South Lusitanian, is a Paleohispanic script used to write an unknown language usually identified as Tartessian...

to be the most ancient paleohispanic script

Paleohispanic scripts

The Paleohispanic scripts are the writing systems created in the Iberian peninsula before the Latin alphabet became the dominant script...

with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c. 825 BC.

Meaning of the name

Researchers use the term "Tartessian" to refer to the language as attested on the stelae written in the southwestern script (Untermann 1997, Koch 2010, &c.) but some researchers would prefer to reserve the term Tartessian for the language of the core Tartessian zone, attested for these researchers with some graffiti (Correa 2009, p. 277; de Hoz 2007, p.33; 2010, pp. 362-364) like the Huelva graffiti (Untermann 1997, pp.102-103; Mederos and Ruiz 2001) and may be with some stelae (Correa 2009, p. 276): for example Villamanrique de la Condesa (J.52.1). These researchers consider that the language of the inscriptions found outside the core Tartessian zone would be either a different language (Villar 2000, p. 423; Rodríguez Ramos 2009, p.8; de Hoz 2010, p.473) or maybe a Tartessian dialect (Correa 2009, p.278), and so they would prefer to identify the language of the stelae with a different title, namely "southwestern" (Villar 2000; de Hoz 2010) or "south-Lusitanian" (Rodríguez Ramos 2009). There is general agreement that the core area of Tartessos is around HuelvaHuelva

Huelva is a city in southwestern Spain, the capital of the province of Huelva in the autonomous region of Andalusia. It is located along the Gulf of Cadiz coast, at the confluence of the Odiel and Tinto rivers. According to the 2010 census, the city has a population of 149,410 inhabitants. The...

extending to the valley of the Guadalquivir

Guadalquivir

The Guadalquivir is the fifth longest river in the Iberian peninsula and the second longest river to be its whole length in Spain. The Guadalquivir is 657 kilometers long and drains an area of about 58,000 square kilometers...

, while the area under Tartessian influence is much wider (Koch 2010 2011 - see maps). Three of the 95 stelae plus some graffiti, belong to the core area: Alcala del Rio (J.53.1), Villamanrique de la Condesa (J.52.1) and Puente Genil (J.51.1). Four have also been found in the Middle Guadiana (in Extremadura) and the rest have been found in the south of Portugal (Algarve and Lower Alentejo) where the Greek and Roman sources locate the Pre-Roman Cempsi and Saefs

Saefs

The Saefs were a Celtic people. An Early Hallstatt culture, they were first in what is now the Czech-German area and later in Iberia...

, Cynetes

Cynetes

The Cynetes or Conii were one of the pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, living in today's Algarve and Low Alentejo regions of southern Portugal before the 6th century BCE .They are often mentioned in the ancient sources under various designations, mostly Greek or Latin derivatives of their...

and the Celtici

Celtici

]The Celtici were a Celtic tribe or group of tribes of the Iberian peninsula, inhabiting three definite areas: in what today are the provinces of Alentejo and the Algarve in Portugal; in the Province of Badajoz and north of Province of Huelva in Spain, in the ancient Baeturia; and along the...

peoples.

History

The most confident dating is for the Tartessian inscription (J.57.1) in the necropolis at Medellin, Badajoz, Spain to 650/625 BC. Further confirmatory dates for the Medellin necropolis include painted ceramics of the 7th-6th centuries BC.In addition a graffito on a Phoenician sherd dated to the early to mid 7th century BC and found at the Phoenician settlement of Doña Blanca near Cadiz has been identified as Tartessian, but is only two signs long. The lecture of the graffito was ]tetu[ or may be ]tute[ and it doesn't show the syllable-vowel redundancy characteristic of the southwestern script (Correa and Zamora 2008).

The script used in the mint of Salacia (Alcácer do Sal

Alcácer do Sal

Alcácer do Sal is a municipality in Portugal, located in Setúbal District. It has a total area of and a total population of 13,624 inhabitants.-History :-Earliest settlement:...

, Portugal) from around 200 BCE may be related to the tartessian script, though it has no syllable-vowel redundancy, violations of this are known, but it is not clear if the language of this mint corresponds with the language of the stelae (de Hoz 2010).

The Turdetani

Turdetani

The Turdetani were ancient people of the Iberian peninsula , living in the valley of the Guadalquivir in what was to become the Roman Province of Hispania Baetica...

of the Roman period are generally considered the heirs of the Tartessian culture. Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

mentions that "The Turdetanians are ranked as the wisest of the Iberians; and they make use of an alphabet, and possess records of their ancient history, poems, and laws written in verse that are six thousand years old, as they assert." It is not known when Tartessian ceased to be spoken, but Strabo (writing c. 7 BCE) records that "The Turdetanians ... and particularly those that live about the Baetis, have completely changed over to the Roman mode of life, not even remembering their own language any more."

Writing

.jpg)

Southwest script

The Southwest Script or Southwestern Script, also known as Tartessian or South Lusitanian, is a Paleohispanic script used to write an unknown language usually identified as Tartessian...

, also known as the Tartessian or South-lusitanian script. Like all the paleohispanic scripts

Paleohispanic scripts

The Paleohispanic scripts are the writing systems created in the Iberian peninsula before the Latin alphabet became the dominant script...

, with the exception of the Greco-Iberian alphabet

Greco-Iberian alphabet

The Greco-Iberian alphabet is a direct adaptation of an Ionic variant of a Greek alphabet to the specifics of the Iberian language, thus this script is an alphabet and lacks the distinctive characteristic of the rest of paleohispanic scripts that present signs with syllabic value, for the...

, Tartessian uses syllabic glyphs for plosive consonants and alphabetic letters for other consonants. Thus it is a mixture of an alphabet

Alphabet

An alphabet is a standard set of letters—basic written symbols or graphemes—each of which represents a phoneme in a spoken language, either as it exists now or as it was in the past. There are other systems, such as logographies, in which each character represents a word, morpheme, or semantic...

and a syllabary

Syllabary

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent syllables, which make up words. In a syllabary, there is no systematic similarity between the symbols which represent syllables with the same consonant or vowel...

, a system called a semi-syllabary

Semi-syllabary

A semi-syllabary is a writing system that behaves partly as an alphabet and partly as a syllabary. The term has traditionally been extended to abugidas, but for the purposes of this article it will be restricted to scripts where some letters are alphabetic and others are syllabic.-Iberian...

. Some researchers believe these scripts are descended solely from the Phoenician alphabet

Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet, called by convention the Proto-Canaanite alphabet for inscriptions older than around 1050 BC, was a non-pictographic consonantal alphabet, or abjad. It was used for the writing of Phoenician, a Northern Semitic language, used by the civilization of Phoenicia...

, others that the Greek alphabet

Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet is the script that has been used to write the Greek language since at least 730 BC . The alphabet in its classical and modern form consists of 24 letters ordered in sequence from alpha to omega...

had an influence as well.

The Tartessian script is very similar to the southeastern Iberian script

Southeastern Iberian script

The southeastern Iberian script, also known as Meridional Iberian, was one of the means of written expression of the Iberian language, which was written mainly in the northeastern Iberian script and residually by the Greco-Iberian alphabet...

, both in the shapes of the signs and in their values. The main difference is that southeastern Iberian script does not redundantly mark the vocalic values of syllabic characters. This was discovered by Ulrich Schmoll and allows the classification of most of the characters into vowels, consonants and syllabic characters. Unlike the northeastern Iberian script

Northeastern Iberian script

The northeastern Iberian script is also known as Levantine Iberian or Iberian, because it is the Iberian script that was most frequently used, and was the main means of written expression of the Iberian language. The language is also expressed by the southeastern Iberian script and by the...

the decipherment of the southeastern Iberian script

Southeastern Iberian script

The southeastern Iberian script, also known as Meridional Iberian, was one of the means of written expression of the Iberian language, which was written mainly in the northeastern Iberian script and residually by the Greco-Iberian alphabet...

and specially the southwestern script is not still closed, because there are a significant group of signs without consensus value among the researchers that study this script (Correa 1989, Untermann 1990, Correia 1996, Rodríguez Ramos 2002; de Hoz 2010). Nevertheless, it is commonly accepted that Tartessian did not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced consonants—[t] from [d], [p] from [b], or [k] from [ɡ].

Classification attempts

Tartessian is usually treated as unclassified (Correa 2009, Rodríquez Ramos 2002, de Hoz 2010) though several researchers had tried to relate Tartessian with known families of languages with the strongest claim being for a CelticCeltic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

affiliation:

- AnatolianAnatolian languagesThe Anatolian languages comprise a group of extinct Indo-European languages that were spoken in Asia Minor, the best attested of them being the Hittite language.-Origins:...

:- Positive: S. Wikander (1966) had proposed that the formulaic expression bare nabe keenti/keeni, was parallel to the Lycian form sijenii found in funerary inscriptions and equivalent to Latin situs est. This would be the PIE root *k´ei- 'to lie' (cfr. Greek keimai, Sanskrit śéte) with a suffix equal to that of the Hittite type ijannai verbs. According to Wikander, the flexion keenti/keeni indicate respectively the singular and the plural as in the Anatolian conjugation *-hi. Also in nabe we should recognize the PIE ending *- bhi, which indicates the locative case. Another element of the alleged Anatolian affinity is an ending -el that would indicate the genitive case.

- Negative: Rodríguez Ramos (2002) refuses the Anatolian hypothesis, because he argues that the morpheme -ti is incompatible with Anatolian phonetics.

- Celtic:

- Unclassified language with Celtic features: Some Tartessian features are interpreted as Celtic or Indo-European, but the largest part of the language remains inexplicable from the Celtic or Indoeuropean point of view.

- Positive: Correa (1989, 251) had identified some Indo-European or Celtic names and elements in the Tartessian inscriptions and suggested the possible adscription of the Tartessian language to the Celtic family. Untermann (1997) added other names and elements with possible Indo-European or Celtic interpretation. Ballester (2004) thought some Tartessian elements have a Celtic character. Villar in 2004 suggested that Tartessian inscriptions contain items of 'an early Gaulish' within a non-Celtic and probably non-Indo-European matrix language making the point that the Celtic in the Tartessian inscriptions shows some linguistic features more akin with those in Gaulish than in Celtiberian.

- Negative: Correa (1995, p. 612) in later works had abandoned this hypothesis, mainly for the absence on Tartessian of the expected nominal declination of a Celtic or western Indo-European language. Rodríguez Ramos (2002, 90-91) refuses the Celtic hypothesis, because he argues that the vocalism of the anthroponyms found in the inscriptions is incompatible with Celtic phonetics. Although he doesn't reject the Indo-European hypothesis, he still considers it as highly unlikely. De Hoz (401-402) points to the absence of significant evidence of Indo-European verbal inflection and indicates that the supposed Indo-European evidence in southwestern inscriptions are scarce and the result of conflicting segmentations based only on the possibility of getting something apparently Indo-European, leaving behind extensive waste that cannot be interpreted in the same way. In addition, agrees with previous Rodriguez Ramos (2002, 90-91) arguments about vocalism and points out that the structure of syllables and words are not identified at all with what we would expect in an Indo-European language.

- Fully Celtic language with non-Celtic borrowings: Tartessian language is interpreted as a fully Celtic language, so the Tartessian inscriptions can be translated.

- Positive: Koch (2010 and 2011) claims that much of the Tartessian corpus can be interpreted as Celtic, with forms possibly of sufficient density to support the conclusion that Tartessian was a Celtic language, rather than a non-Celtic language containing a relatively small proportion of Celtic names and loanwords. Koch (2011 p. 2) claims that Francisco Villar now maintains that Tartessian is a language in the Celtic family. Koch maintains he has achieved valid segmentations and has established Indo-European inflections such as for the verb stem naŕkee- which he thinks means the equivalent of "rest in peace" from Indo-European *(s)ner- 'bind, fasten with thread or cord' (cf. Greek for 'grow stiff, numb, dead') and the possible Common Celtic verb stem *lag- (cf.Old Irish laigid meaning 'lies down')' from Indo-European *legh meaning 'lie', e.g. for present 3rd plural active:

- naŕkeeni (J.1.2, J.7.2)

- naŕkeentii (J.12.1, J.16.1, J.18.1, J.19.2)

- naŕkeenii (J.2.1)

- naŕken (J.7.5)

- lakiintii (J.12.4) (suggested pronunciation laginti)

- lakeentii (J.53.1)

- ]ntii at the end a fragmentary inscription (Monto Novo do Castelinho)

- Negative: A critical view of Koch's work that considers that it is not really convincing and that points out inconsistencies, in form and content, and ad hoc solutions, but recognizes that it is a strong vote for the Celtic hypothesis, can be found at Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2011.09.57.

- Positive: Koch (2010 and 2011) claims that much of the Tartessian corpus can be interpreted as Celtic, with forms possibly of sufficient density to support the conclusion that Tartessian was a Celtic language, rather than a non-Celtic language containing a relatively small proportion of Celtic names and loanwords. Koch (2011 p. 2) claims that Francisco Villar now maintains that Tartessian is a language in the Celtic family. Koch maintains he has achieved valid segmentations and has established Indo-European inflections such as for the verb stem naŕkee- which he thinks means the equivalent of "rest in peace" from Indo-European *(s)ner- 'bind, fasten with thread or cord' (cf. Greek for 'grow stiff, numb, dead') and the possible Common Celtic verb stem *lag- (cf.Old Irish laigid meaning 'lies down')' from Indo-European *legh meaning 'lie', e.g. for present 3rd plural active:

- Unclassified language with Celtic features: Some Tartessian features are interpreted as Celtic or Indo-European, but the largest part of the language remains inexplicable from the Celtic or Indoeuropean point of view.

Texts

Examples from the Tartessian inscriptions (Untermann's numbering system or location name if newer in brackets references the inscriptions in the examples, e.g. (J.19.1) or (Mesas do Castelinho)):- Mesas do Castelinho (Almodôvar) – longest Tartessian text known at present with 82 signs (80 of which have an identifiable phonetic value) and complete with substitution of well-known Tartessian formula baare naŕkee[n--] in damaged portion: (Guerra 2009)

1) tiilekuurkuuarkaastaabuuteebaantiilebooiirerobaarenaŕke[en---]aφiuu

2) lii*eianiitaa

3) eanirakaalteetaao

4) beesaru?an

Notes:

- tiilekuur is proposed as a personal name.

- [en---] depends on the Indo-European inflection that applies in this case to the damaged portion containing the well-known Tartessian formula baare naŕkee[n---]. This formula contains two groups of Tartessian stems that appear to be inflected as verbs: naŕkee, naŕkeen, naŕkeeii, naŕkeenii, naŕkeentii, naŕkeenai and baare, baaren, baareii and baarentii from considering other inscriptions. (Guerra 2009)

- Fonte Velha (Bensafrim) (J.53.1):

'lokoobooniirabootooaŕaiaikaalteelokonanenaŕ[-]ekaa?iiśiinkoolobooiiteerobaarebeeteasiioonii (Untermann 1997)

- Herdade da Abobada (Almodôvar) (J.12.1)

ir´ualkuusie : naŕkeentiimubaateerobaare?aataaneatee (Untermann 1997)

See also

- ArganthoniosArganthoniosArganthonios was a king of ancient Tartessos .This name, or title, appears to be based on the Indo-European word for silver and money *arģ-, found in Celtiberian arkanta, Old Irish airget, Latin argentum, Sanskrit rajatám. Tartessia and all of Iberia was rich in silver. Similar names Arganthonios...

- Celtiberian languageCeltiberian languageCeltiberian is an extinct Indo-European language of the Celtic branch spoken by the Celtiberians in an area of the Iberian Peninsula lyingbetween the headwaters of the Duero, Tajo, Júcar and Turia rivers and the Ebro river...

- Gallaecian languageGallaecian languageThe Northwestern Hispano-Celtic, Gallaecian or Gallaic, is classified as a Q-Celtic language under the P-Q system and was closely related to Celtiberian...

- Hispano-Celtic languages

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian PeninsulaPre-Roman peoples of the Iberian PeninsulaThis is a list of the Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian peninsula .-Non-Indo-European:*Aquitanians**Aquitani**Autrigones - some consider them Celtic .**Caristii - some consider them Celtic ....

- Continental Celtic languagesContinental Celtic languagesThe Continental Celtic languages are the Celtic languages, now extinct, that were spoken on the continent of Europe, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of Britain and Ireland. The Continental Celtic languages were spoken by the people known to Roman and Greek writers as Keltoi,...

Further reading

- Ballester, Xaverio (2004): «Hablas indoeuropeas y anindoeuropeas en la Hispania prerromana», Estudios de lenguas y epigrafía antiguas – ELEA 6, pp. 107–138.

- Broderick, George (2010): «Das Handbuch der Eurolinguistik», Die vorrömischen Sprachen auf der iberischen Halbinsel, ISBN 3447059281, pp. 304–305

- Correa, José Antonio (1989): «Posibles antropónimos en las inscripciones en escritura del S.O. (o Tartesia)» Veleia; 6, pp. 243–252.

- Correa, José Antonio (1995): «Reflexiones sobre la epigrafía paleohispánica del suroeste de la Península Ibérica», Tartessos 25 años después, pp. 609-618.

- Correa, José Antonio (2009): «Identidad, cultura y territorio en la Andalucía prerromana a través de la lengua y la epigrafía», Identidades, culturas y territorios en la Andalucía prerromana, eds. F. Wulff Alonso y M. Álvarez Martí-Aguilar, Málaga, pp. 273-295.

- Correa, José Antonio, Zamora, José Ángel (2008): «Un graffito tartessio hallado en el yacimiento del Castillo do Dona Blanca», Palaeohispanica 8, pp. 179–196.

- Correia, Virgílio-Hipólito (1996): «A escrita pré-romana do Sudoeste peninsular», De Ulisses a Viriato: o primeiro milenio a.c., pp. 88–94

- Guerra, Amilcar (2002): «Novos monumentos epigrafados com escrita do Sudoeste da vertente setentrional da Serra do Caldeirao», Revista portuguesa de arqueologia 5-2, pp. 219–231.

- Guerra, Amilcar (2009): «Novidades no âmbito da epigrafia pré-romana do sudoeste hispânico» in Acta Palaeohispanica X, Palaeohispanica 9, pp. 323-338.

- Hoz, Javier de (1995): «Tartesio, fenicio y céltico, 25 años después», Tartessos 25 años después, pp. 591–607.

- Hoz, Javier de (2007): «Cerámica y epigrafía paleohispánica de fecha prerromana», Archivo Español de Arqueología 80, pp. 29-42.

- Hoz, Javier de (2010): Historia lingüística de la Península Ibérica en la antigüedad: I. Preliminares y mundo meridional prerromano, Madrid, CSIC, coll. « Manuales y anejos de Emerita » (ISBN 978-84-00-09260-3, eISBN 978-84-00-09276-4).

- Koch, John T.John T. KochProfessor John T. Koch is an American academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies, especially prehistory and the early Middle Ages....

(2010): «Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic», Oxbow Books, Oxford, ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4 pp. 187-295. - Koch, John T.John T. KochProfessor John T. Koch is an American academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies, especially prehistory and the early Middle Ages....

(2011): «Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology», Oxbow Books, Oxford, ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3 pp. 1–198. - Mederos, Alfredo; Ruiz, Luis (2001): «Los inicios de la escritura en la penënsula ibérica. Grafitos en cerámicas del bronce final III y fenicias», Complutum 12, pp. 97-112.

- Mikhailova, T. A. (2010) Review: "J.T. Koch. Tartessian: Celtic in the South-West at the Dawn of history (Celtic Studies Publication XIII). Aberystwyth: Centre for advanced Welsh and Celtic studies, 2009" Вопросы языкознания 2010 №3; 140-155.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002): «Las inscripciones sudlusitano-tartesias: su función, lingua y contexto socioeconómico», Complutum 13, pp. 85–95.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2009): «La lengua sudlusitana», Studia Indogermanica Lodziensia VI, pp. 83-98.

- Untermann, JürgenJürgen UntermannJürgen Untermann is a German linguist, indoeuropeanist and epigraphist.A disciple of Hans Krahe and of Ulrich Schmoll, he studied at the University of Frankfurt and the University of Tübingen...

, ed. (1997): Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum. IV Die tartessischen, keltiberischen und lusitanischen Inschriften; unter Mitwirkungen von Dagmar Wodtko. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert. - Untermann, JürgenJürgen UntermannJürgen Untermann is a German linguist, indoeuropeanist and epigraphist.A disciple of Hans Krahe and of Ulrich Schmoll, he studied at the University of Frankfurt and the University of Tübingen...

(2000): «Lenguas y escrituras en torno a Tartessos» en ARGANTONIO. Rey de Tartessos, Madrid, pp. 69–77. - Villar, Francisco (2000): Indoeuropeos y no indoeuropeos en la Hispania prerromana, Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca (ISBN 978-84-78-00968-8).

- Villar, Francisco (2004): «The Celtic Language of the Iberian Peninsula», Studies in Baltic and Indo-European Linguistics in Honor of William R. Schmalstieg pp. 243–274.

- Wikander, Stig (1966): «Sur la langue des inscriptions Sud-Hispaniques», in Studia Linguistica 20, 1966, pp. 1-8.